Gas Warfare

|

| Gassed by John Singer Sargent |

|

"[The] vapor settled to the ground like a swamp mist and drifted toward the French trenches on a brisk wind. Its effect on the French was a violent nausea and faintness, followed by an utter collapse. It is believed that the Germans, who charged in behind the vapor, met no resistance at all, the French at their front being virtually paralyzed." The use of gas at Langemarck ø as reported in the New York Tribune, April 27, 1915 The horrors of gas warfare had never been seen on a battlefield until 1915. The Germans have been credited with the first use, but the French and English were not far behind. Gas was a nuisance, a crippling nuisance, often only wounding and causing widespread panic instead of outright killing. Add a gas mask to the already surreal atmosphere of an offensive's rolling bombardments and heavy machine gun fire, and what you got must have been close to hell. (See the paintings "Hell" by Leroux and "Soldats Masques" by Zingg in The Fractal Gallery. They convey the experience of gas warfare better than any photographs.) | |

|

The first army issue gas masks were little more than gauze bandages with ties. These would be moistened with water to improve their effectiveness in filtering out the gas. |

|

The cannister gas mask was developed to protect the soldier from the use of chlorine gas and tearing agents such as xylyl bromide. This type of mask was not effective in filtering out the more deadly phosgene and diphosgene gases. There was no mask that could offer protection from the blistering mustard gas which attacks all exposed flesh. |

|

The first reported use of gas was by the Germans on the eastern front on 3-Jan-1915. It was a tearing agent dispersed by artillery shell. The first use on the western front came several months later on 22-Apr-1915 at the village of Langemarck near Ypres. At 1700 hours the Germans released a 5 mile wide cloud of chlorine gas from some 520 cylinders (168 tons of the chemical). The greenish-yellow cloud drifted over and into the French and Algerian trenches where it caused wide spread panic and death. The age of chemical warfare had begun. | |

|

An aerial view of the beginning of a gas attack. Large gas cylinders were brought up to the front where the gas would be released under favorable wind conditions. On more than one occasion the wind would change direction and blow the gas back into the attacker's trenches. |

|

British gas casualties near Bois de l'Abbe France, May 1918. The eye bandages indicate that a blistering agent such as mustard gas was used. This gas was named for it's similarity in both faint smell and color to mustard. |

| The British were ready to return the favor by early autumn. On 25-Sep-1915 they released chlorine gas from cylinders against the German trenches at Loos. Unfortunately a shift in the wind blew the gas laterally across the trench lines so that it also gassed some British troops. The use of cylinder gas was replaced with the safer gas artillery shell and projector. The projector was a device that lobbed a football size gas projectile into the enemy trench. The idea with both was to get the gas as far from friendly forces as possible before releasing it. Artillery men were soon referring to "yellow crosses" and "white crosses" - these were the markings used to differentiate the various gas shell types. | |

|

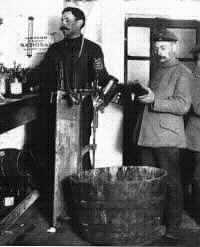

A makeshift German gas laboratory near the front. The gas concentrate is stored in bottles for placement near enemy trenches. Sniper fire would then be used to break the bottle and release the gas. |

|

Gas was invented (and very successfully used) as a terror weapon meant to instill confusion and panic among the enemy prior to an offensive. It was a sort of physiological weapon with the non-lethal tearing agents inflicting as much panic as the dreaded mustard gas. Gas was available in three basic varieties:

| |

|

German signal corps soldiers placing their carrier pigeons in a shelter during a gas attack. |

|

Gas masked British soldiers manning a Vickers machine gun. |

|

In the great carnage of 1916-17 there were approximately 17,700 gas casualties counting the Somme, Chemin des Dames, and Passchendaele alone. These numbers would grow considerably higher due to the large number of deaths after the war that would be directly attributed to gas exposure. Despite this high casualty count for both sides, the use of gas continued to grow. By 1918, one in every four artillery shells fired contained gas of one type or another. In 1918 a German corporal by the name of Adolf Hitler was temporarily blinded by a British gas attack in Flanders. Having suffered the agonies of gas first hand, his fear of the weapon would prevent him from deploying it as a tactical weapon on the battlefields of the Second World War. | |