A Special Contribution Courtesy of

|

|||||||

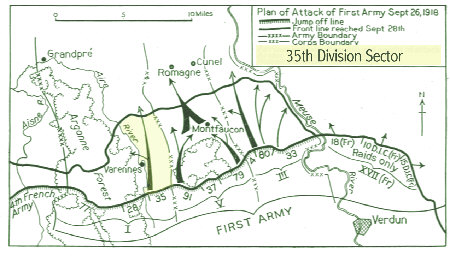

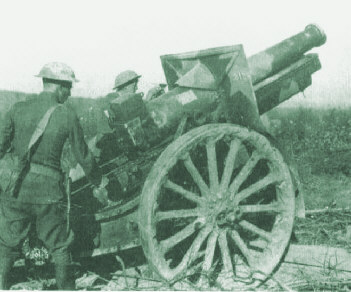

Professor Ferrell writes:For the Americans there was the continuing problem of artillery support. During these opening days in the Meuse-Argonne, the U.S. Army commanders could not quite grasp what was necessary. Going into the Meuse Argonne the AEF had known of the gigantic preparation fire and barrages of [German] Lieutenant Colonel Georg Bruchmueller. Some of the American commanders appreciated the need of infantry for fire that would destroy or hold down opponents. Artillery had long been a specialty of the U.S. Army. At Gettysburg, the classic battle of the Civil War, Union artillery had decimated General George Pickett's line. The army could hardly ignore its achievement in 1863, and its experts kept in touch with developments abroad. The army's three-inch field gun was as good as the French 75. But the other arms appear to have taken priority. The army's three-inch gun could not be produced rapidly enough, once war was declared, and it was necessary to use French guns.The army's artillery organization in 1917-1918, which designated one artillery brigade for each division, with two regiments of light three-inch guns and one regiment of heavy I55s, tended to persuade each division commander that one artillery brigade was enough and, moreover, if another division desired two, that was its problem. When a division went into the line for the first time it often found its artillery brigade unready, in which case it could lay claim to another division's brigade. Normally, however, each kept its own and felt satisfied.  35th Division Sector in Meuse Argonne AttackIt is saddening, too, that experience was to teach the AEF artillerists to vary the nature of the shells, so that when they were trying to take out the enemy's artillery the shells would be full of high explosive, while if enemy troops were the target the necessity was shrapnel. If they could get guns close enough, flat trajectory with its ricochet was the thing, rather than hole-digging. In the early days commanders fired what they had on hand. It is true that there were supply problems in obtaining stocks for special purposes. But there was no imagination in asking for the right sort of shells at supply dumps, nor in bringing up the guns. During the action of the Thirty-fifth Division on September 29, as on the four days that preceded, the artillery brigade used no gas shells, and there again, as in the general use of artillery~ it and the other divisions learned by experience. The Germans had employed gas shells from the beginning of the Meuse-Argonne. Colonel Wieczorek was gassed the first day. It was possible to contend that a good soldier would avoid gas, and there was some truth in that argument. When the Germans were attacking American troops in Montrebeau Woods they drenched the place; all low areas, especially ravines, were dangerous, and a good infantryman could keep that point in mind. Luck, as well as care, could save men. A member of the 110th Engineer Regiment manning the hastily improvised engineers' line that would save the division on September 29 remarked in his memoir of many years later that at the time he was so glad the weather turned cold, for it kept down the gas.3 But gas, even if controlled by the men who had to live close to it, was a terrible nuisance, and this was a part of the calculation of the German enemy that employed it. Troops in the woods were forced to stay there with masks, which were difficult to use because of trouble with breathing, and also because the circled eyeglasses fogged up.  Artillery Brigade Command Staff, BG Berry with MustacheOn the morning of September 29 It was too soon in the AEF's developing understanding of gas warfare to use gas against the First and Fifth Guards divisions and the arriving German Fifty-second Division and avoid defeat of the U.S. Thirty-fifth Division. Of the quarter million Americans killed and wounded in the war, gas shells caused one-third of the casualties (shell and shrapnel half, and rifle and machine-gun fire one-tenth). In the artillery fire that accompanied the attack on September 29, and despite the need for artillery brigadiers to have experience, Berry made several miscalculations that seem inexcusable. One was to assign the 130th Artillery Regiment of heavy howitzers a fire by the map that would stand one kilometer north of Exermont until the rolling barrage, to be fired by the 128th and 129th regiments of light guns, moved up to that line, whereupon the 130th was to lift its fire to the German batteries at Chatel-Chehery. A standing fire north of Exermont might have prevented the Germans from reinforcing their defenses in Exermont, on Hill 240, known as Montrefagne, and in the Bois de Boon on top of it. Fire on the flanking batteries in Chatel-Chehery might have cut down on their fire during the infantry attack. But the division's infantry available for the attack was not strong on the right-hand side of the division sector, what with the 138th weakened by stretching to the right to cover the four-kilometer gap. On the left-hand side of the Thirty-fifth's sector the 137th had disintegrated and the 139th was starting to go. Both sides were in trouble and needed every artillery piece firing in the barrage, including the heavy howitzers of the 130th.  French 155s Fired by the 130th Field ArtilleryThere was a third miscalculation on Berry's part. This, as one would have expected, was his guns' rate of fire. Jacobs believed they fired two shots per minute or less. The War College study says that each battery rested one gun while the others fired four shots per minute. Its estimate seems to be based on figures for shells fired that day, and those figures are not altogether clear, for they may well have been for shells on hand-in any event, to start with the number of shells and move back to the number of guns firing and the firing rate appears to be an uncertain way of calculation. After the war Colonel Klemm of the 129th told the newspaper that the guns were firing two shots per minute. That rate of fire, or four shots (one gun resting), was hardly what the 155 might have done. And there is no evidence in the War College study that there was any shortage of ammunition, despite Berry's explanation to Jacobs that he was running out. A final miscalculation in Berry's barrage was that he began it two hundred meters south of Exermont. The distance from the top of Montrebeau Woods to Exermont was one thousand meters. This meant that the area in between, eight hundred ~meters, was not covered. During the night of September 28-29 the Germans sent machine gunners down from Exermont and covered it-against the attacking troops of the Thirty-fifth Division.  Battery D, 129th Field Artillery Firing |

|||||

To find other features on the DOUGHBOY CENTER visit our

Additions and comments on these pages may be directed to:

Michael E. Hanlon (greatwar@earthlink.net)