Harry Andrews and the Legend of Chateau La Roche

| Chateau La Roche; Somewhere in Ohio, not France. Over a million visitors have passed through the main gate. |

Photos and text contributed by Lori Jareo (ljareo@mail.gardnerweb.com)

|

Harry Andrews and the Legend of Chateau La Roche Harry Andrews’ improbable but true World War I service began in an army hospital. The young man was one of the 7,000 soldiers at Camp Dix, New Jersey, who were cut down by an outbreak of deadly cerebrospinal meningitis. Andrews’ motionless body was moved to a morgue, and his records were marked "deceased" and sent to Washington.

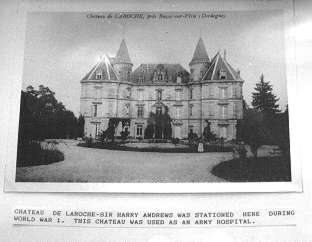

Harry Andrews was on the slab for some time. The body was then taken back to the hospital for dissection. Doctors opened the mouth, cutting away tissue from the upper palate for bacterial cultures. One of the doctors said, "Let’s see if we can start his heart with this new stuff." The "new stuff" was adrenaline. A needle pierced his heart and the doctors punched his chest. Then his heart began to beat again. Andrews was blind and paralyzed, and no one expected him to live. After a few weeks, he could sit up and eat. He weighed 89 pounds and was fed six times daily, sometimes gaining two or three pounds a day. Andrews’ sight came back, but he had to wear glasses. Later, doctors removed his blood to obtain meningococcus antibodies, and he became a blood bank to save others from the disease. Only one other Camp Dix soldier survived the initial outbreak. Sometime later, Andrews found himself stationed at an army hospital at the Chateau La Roche, pres Razac-sur-l’Isle, in the Dordogne region of southwest France. There he served as a hospital administrator. Europe in 1918 was an unpleasant place, and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson decried the violence, chaos and depravity of the day. Andrews simply called it "Hell." Nevertheless, the 28-year-old served his country well; he was also active in the YMCA and he taught French to American soldiers. Andrews, who studied architecture at Colgate University, also studied architecture at Toulouse University after the war.

Like most returning doughboys, Andrews brought back a few ordinary souvenirs: his nurse cap, his mess kit and some postcards. But because of his architectural studies, he also brought back an idea for something extraordinary. In 1927, Andrews purchased land along the Little Miami River in Loveland, Ohio (near Cincinnati). He intended to provide a place for his Sunday School class of young men to swim, fish and camp. The boys slept in tents, but after a few summers, the tents had decayed. He told the boys to gather stones from the river. From these, he built two small rooms, which he called a "stone tent." From this stone tent, Andrews formed the Knights of the Golden Trail. Based on the Ten Commandments and principles of chivalrous knighthood, the purpose of this organization was to save modern civilization from degradation and degeneration, just as noble knights saved Europe from the Dark Ages. Of course, the knights would need a castle to meet in. Thus, on June 5, 1929, Chateau La Roche, or "Rock Castle," was begun. In 1930, the castle was dedicated.

Because of the Depression and the Second World War, Andrews did not earnestly begin work on the castle until he retired. An only child who never married, he lived in the castle as he built it. It was modeled after the castles in northern France and the British isles, and it is a one-fifth scale replica of a 16th-century medieval castle. Chateau La Roche sits on one-and-one-half acres of land. The grounds measure 96 by 56 feet. Measured at the castle’s eastern face, it rises 36 feet above ground. The castle is 647.8 feet above sea level. The Chateau has a kitchen, bathroom, living room, office, dining room, bedroom, balcony, fighting deck with fireplace grill, garage, junk room, dungeon, terrace and garden. The castle has many of the amenities of a modern home. It has a water pump, septic tank, oil-burning furnace, electricity, running water, sewers and telephone. Bricks are an important part of any castle, especially at Chateau La Roche. All of the bricks are made from concrete, formed by quart-sized paper milk cartons. More than 2,600 sacks of cement have been used in their making. Some bricks contain light bulbs or tin cans for reasons of thrift and insulation. Mr. Andrews, who did 98 percent of the work himself, carried an estimated 56,000 pails of stones in five- gallon buckets (65 pounds each) by hand up from the river. The material in the castle weighs approximately 8,000 tons. Andrews committed 23,000 hours of hard labor and $12,000. For his efforts, he received more than 50 proposals of marriage from "widows and old maids who wanted to live in a castle."

Chateau La Roche received a lot of media attention. Andrews appeared on TV at least 50 times on local stations as well as on stations in Cleveland, Louisville and Pittsburgh. Numerous radio, newspaper and magazine pieces have also been written. During his lifetime, Andrews taught at several Cincinnati area schools, worked as a reporter and did defense work during World War II. He retired from the Standard Publishing Co., where he worked in the mailroom. Andrews also taught Sunday School for 30 years. On Memorial Day, 1955, with a few rooms completed and a few amenities installed, Andrews moved into the castle. When Andrews applied for his Army pension, he had to convince the Pentagon that he wasn’t dead. After receiving the pension for 23 years, it stopped coming in 1979. For the last few years of his life, he got by on Social Security. On the morning of March 14, 1981, Andrews lit a trash fire on castle grounds. As he tried to stomp it out, his trousers caught fire, as did his sleeves. Alert visitors at the castle covered him with a blanket and put out the fire. Nevertheless, he suffered severe burns on his legs and arms. Although skin- graft operations at a nearby hospital went well, Harry Andrews passed away from his injuries on April 16, 1981.

If any visitor to the Chateau asks a castle caretaker for the facts about Harry Andrews, he will point him or her to display cases and mounted newspaper clippings. The nurse cap and Camp Dix experience are there. But ask for the story of Harry Andrews, and he or she will get something comparable to the legends of Sergeant York, Eddie Rickenbacker or even the Red Baron. At Chateau La Roche, Andrews pulled the son of an English nobleman off the battlefield. The grateful father knighted Andrews for his service. Few details are available, but this story may be one of the greatest legends of them all.

The author would like to thank the Knights of the Golden Trail for their assistance with this article. Lillian Weitkamp, vice president of human resources, Standard Publishing Co., also provided invaluable information. Photographs (except where noted) and article © 1996 L.E. Jareo

|