Assault on the Viribus Unitis

|

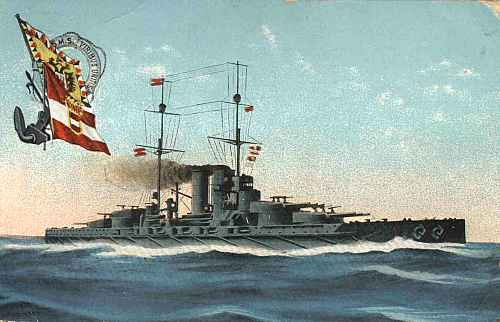

| The Viribus Unitis as pictured on an Austrian postcard (courtesy of Jim Simon). |

Contributed by Paul Chrastina (Chrastina@aol.com) and Old News

|

This article originally appeared in the Jan/Feb 1998 issue of Old News (Vol 9, No 5) under the title Italian Frogmen Attack Austrian Dreadnought. It is reproduced here with permission. If you have a little time to spare, you should follow this link to the ø Old News web site. While it's not dedicated to WWI, you never know what type of articles you'll find there but they're always history and they're always interesting. |

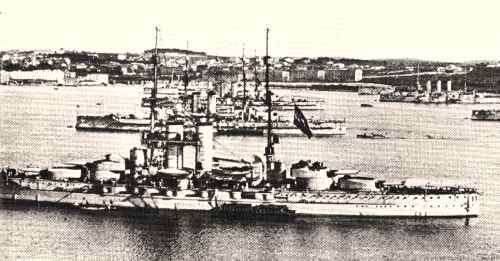

Assault on the Viribus Unitisby Brian WarholaIn the summer of 1918, as World War One was drawing to close, the Austrian navy suffered a series of defeats at the hands of the Royal Italian Navy. The most powerful ships of the Austrian navy retreated to the port of Pula, on the Adriatic Sea. The entrance to this harbor was protected by floating booms and barricades, designed to ensnare and destroy enemy ships. The Italian navy made several attempts to attack the Austrian fleet at Pula, but failed to breach the elaborate harbor defenses. Lieutenant Raffaele Paolucci was an Italian naval surgeon who devised a plan to infiltrate the harbor at Pula and destroy the largest ships of the Austrian fleet. Although the sheltered enemy fleet seemed invulnerable to conventional attack, it occurred to Lieutenant Paolucci that he might be able to reach the Austrian ships by simply swimming to them, carrying explosives. Paolucci consulted charts of the Pula estuary and concluded that, if he could be dropped off near the entrance to the harbor, “a swim of three kilometers would enable me to reach the objective.” Keeping his plan to himself, Paolucci began to train for the task of swimming alone into the harbor at Pula. At night, Paolucci swam for hours in the lagoons of Venice, increasing his endurance until he could comfortably swim five miles without resting. As his stamina increased, Paolucci began dragging a three-hundred-pound keg of water with him, to simulate the weight of an explosive charge he planned to take with him to destroy the enemy ships. In May, confident of his ability to carry out his plan, Paolucci presented the idea to his commanding officers. He was advised of the obvious dangers attending such an undertaking, but was told to continue his training. In July, Paolucci was introduced to Major Raffaele Rossetti. Paolucci learned that Rossetti had designed and built an entirely new kind of aquatic weapon, a manned torpedo that was perfectly fitted to the mission for which Paolucci had been preparing himself. Using the long, slender shell of an unexploded German torpedo that had washed up on the Italian coast, Rossetti had built a sleek submersible craft that could be ridden through the water like a horse. Filled with compressed air that drove two small, silent propellers, Rossetti’s rebuilt torpedo was about twenty feet long, weighed one-and-a-half tons, and could carry a pair of riders through the water at a top speed of two miles an hour. At the front end of the apparatus were fitted two detachable watertight canisters, each of which had room for four hundred pounds of TNT. The craft could be raised or lowered in the water by adjusting a series of control valves Rossetti had designed. In the Italian naval shipyard in Venice, Rossetti and Paolucci practiced swimming and guiding the torpedo. “We had to be in the water,” Paolucci later wrote, “clinging to the machine, which moved slowly; we had to steer it with our bodies, and in certain cases were obliged to drag the apparatus ourselves. . . . we accustomed ourselves to getting over simple obstructions and nets. . . we habituated ourselves to remaining in the water for six or seven hours at a stretch with our clothes on, and to pass ing unobserved beneath the eyes of the sentries posted along the Venice dockyard. . . . we traversed the whole of the dockyard without our passage being perceived either by the numerous sentries, or by the officers in charge of them, who knew that the trial was being made.” On the night of October 31, 1918, the two men and their hybrid water craft were brought within a few miles of the entrance to the harbor at Pula by an Italian navy motorboat. Donning waterproof rubber suits, Rossetti and Paolucci slipped into the water, mounted their torpedo, and set out to sabotage the unsuspecting Austrian fleet. Riding on the incoming tide, Rossetti and Paolucci submerged the torpedo until only their heads rose above the water’s surface. It was 10:13 pm as they set off for Pula. If all went well, Rossetti had calculated that it should take no more than five hours to deliver the explosives to the Austrian ships and return to the waiting Italian motorboat, which lay anchored out of sight of Austrian patrols. As they approached the entrance to the harbor Rossetti shut off the air valve that powered the torpedo’s twin propellers. The two men then carefully guided the torpedo up to the first of the barriers that guarded the outer harbor. Enemy searchlights swept over the water, threatening to expose them to view. Each time, however, the searchlights passed over them without revealing their presence. Reaching the outermost barricade at 10:30, Rossetti and Paolucci found that it was made of “numerous empty metal cylinders, each about three yards in length, between which were suspended heavy steel cables.” After waiting for an opportune moment, the two men lifted and pushed their craft over this obstacle, anxious that the sound of metal scraping on metal might alert Austrian guards on shore. Their struggles went unnoticed. “After great effort,” Paolucci wrote, “we got past the obstruction, when I felt myself seized by the arm. I turned around, to see Rossetti pointing to a dark shape which seemed to be advancing toward us.” An Austrian U-boat, running without lights and with only its conning tower above the water, glided past them and out into the Adriatic Sea, oblivious to their presence. Restarting the torpedo’s motor, the two men steered slowly toward the sea-wall that guarded Pula’s inner harbor. While Rossetti waited in the shadow of the sea-wall, Paolucci swam ahead to look for the easiest entrance to the harbor. Instead, he found another obstruction, a gate made of heavy timbers studded with long steel spikes. Paolucci swam back to Rossetti and told him what he had found. Rossetti decided to continue with the mission. The tide had turned, and the two men now fought the current, dragging the heavy torpedo up to the submerged gate. Cold rain began to fall, mixed with hail. As the two men laboriously hoisted the torpedo over the gate, the noise of their exertions was masked by the sound of icy raindrops hitting the water. Rossetti checked his watch. It was 1:00 AM. They had been in the water for three hours, and had not yet reached their objective. In front of them was an Austrian guard ship. A red light showed the location of a sentry post. Submerging the torpedo, they steered silently past the ship. Expecting their way to be clear, the Italian officers were surprised to find new obstacles to their progress. A series of wire nets armed with explosive charges had been stretched across the entrance to prevent enemy submarines from entering the inner harbor. Rossetti and Paolucci struggled against the ebbing tide to work their way past the nets and reach the anchored Austrian battleships. “At length,” Paolucci wrote, “our endevours were successful.” It was now 3:00 in the morning.

The largest ship, the dreadnought Viribus Unitis, lay closest to shore, and was chosen as the primary target. Swimming through sleet and hail, Rossetti and Paolucci saw the sky begin to brighten with dawn. As they reached the side of the Viribus Unitis, the torpedo unexpectedly began to sink. While Paolucci frantically struggled to keep the torpedo afloat, Rossetti located an intake valve that had accidentally opened, allowing air to escape from the cylinder. After shutting the valve, the two men rested in the shadow of the Austrian flagship for a few minutes. “Of all our trying moments,” Paolucci wrote, “this was undoubtedly the worst.” Working their way down the long line of Austrian battleships, the two men reached the Viribus Unitis at 4:45 am. Rossetti removed one of the canisters of TNT from the front of the torpedo and attached it to the hull of the Viribus Unitis. Rossetti set a timer to detonate the 400-pound charge of TNT at 6:30. As Rossetti and Paolucci pushed off from the side of the Viribus Unitis, they were spotted by a sentry on the flagship.The Italians tried to steer for shore, where they hoped to escape. Quickly, however, a boat was dispatched from the Viribus Unitis to capture them. Paolucci hastily armed the second canister of explosives and set it free in the ebbing tide. Rossetti flooded the torpedo’s air cylinder, letting it sink to the bottom. The Italian officers were captured by sailors from the Viribus Unitis and taken back to the ship. There, they were shocked to learn that during the night the Austrian fleet had mutinied, and that the Austrian admiral had turned command of the Viribus Unitis over to a Yugoslavian captain named Ianko Vukovic. All German and Austrian crew members had been sent ashore, leaving the fleet in the hands of neutral Yugoslavian sailors. It was 6:00 AM. Knowing that in one half-hour the TNT would detonate, Rossetti told Captain Vukovic “Your ship is in serious, imminent danger. Save your men.” Captain Vukovic calmly demanded an explanation. Rossetti said “I cannot tell you; but in a very short time the ship will be blown up.” Vukovic, wasting no time, shouted in German “Men of the Viribus Unitis, save yourselves all who can! The Italians have placed bombs in the ship!” The Yugoslavian crewmen, on hearing this news, panicked and began to abandon ship. “We heard doors open and shut in a hurry, we saw half-naked men rushing about madly and clambering up the steps of the batteries, we heard the noise of bodies splashing into the sea,” Paolucci wrote. Taking advantage of the sudden panic, Rossetti asked Captain Vukovic if they might savc themselves. Vukovic said yes. Rossetti and Paolucci ran to the side of the ship and dove overboard. They were soon overtaken by a group of angry Yugoslavian sailors in a small boat, who took them back to the Viribus Unitis. “We thought,” Paolucci wrote, “that they inte nded to make us die on the doomed ship.” It was 6:20. Back on the deck of the ship for the second time, Rossetti and Paolucci found themselves surrounded by a threatening mob of sailors. “Some of them were shouting that we had deceived them, while others wanted to know where the bombs were hidden.” Rossetti spoke up, demanding that he and Paolucci be granted fair treatment as prisoners of war. Vukovic ordered his men not to harm the Italians. When 6:30 came, there was no explosion. Rossetti and Paolucci stared blankly at one another, wondering if something had gone wrong. Captain Vukovic was still attempting to restore order on the ship’s deck. Around the ship, crewmen who had abandoned the Viribus Unitis rowed in lifeboats, unsure whether to flee to safety or return to the ship. At 6:44 the charge of TNT detonated. Rossetti and Paolucci were surprised that the delayed explosion made only “a dull noise, a deep roaring, not loud or terrible, but rather light.” Immediately, however, a huge column of water rose into the air at the ship’s bow and splashed down on its foredeck. In the moment of shock following the explosion, Rossetti and Paolucci once again asked permission to abandon the ship. Captain Vukovic shook their hands and pointed to a rope by which they could escape into the water, motioning to one of the lifeboats to pick them up. Dragged aboard the small boat, Rossetti and Paolucci turned to watch the Viribus Unitis slowly sink. “The Viribus Unitis heeled over more and more,” Paolucci wrote, “When the water reached the level of the deck, the ship capsized completely. I saw the big turret guns tumbled about like toys. . . . On the keel I saw a man crawling until he reached the top. It was Captain Vukovic. He died a little later, after being struck on the head by a wooden beam when, after having extricated himself from the whirl of water, he was trying to save his life by swimming to shore.” Rossetti and Paolucci were taken as prisoners of war to an Austrian hospital ship to recover. There, they learned that the second canister of explosives, set free by Paolucci just before they were captured, had exploded against the hull of an Austrian ship called Wien, sinking it. Three days later, on November 4, 1918, Italy and Austria signed a peace treaty. The next day the Italian fleet took control of Pula, and Rossetti and Paolucci were freed. The two men were presented with gold medals for courage. Rossetti was awarded 650,000 lire from the Italian government as a reward for his services. He presented this reward to the widow of Captain Vukovic, describing the deceased captain as “a war adversary who, dying, left me with an ineradicable example of generous humanity.” The money was used to establish a trust fund for widows and mothers of other war victims.

|