|

From the Spring 2004 Issue, Volume Thirteen, Number Two:

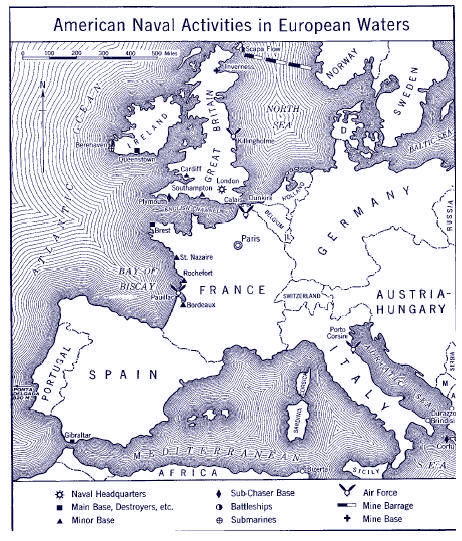

The U.S. Navy in the Great War

By Paul Halpern

The United States Navy entered the First World War in the process of unparalleled expansion. The days of a fleet configured solely for coast defense and the guerre de course against a far stronger foe, such as the Royal Navy, were long gone. Moreover, the most likely enemies had changed. They were now Germany, reflected in

War Plan BLACK, and Japan, covered by War Plan ORANGE. In 1903, the General Board of the U.S. Navy had set as its goal for 1920 a force of

forty-eight battleships with a set ratio of support ships. For every two battleships there would be one armored cruiser, three "protected" cruisers, four scout cruisers, three destroyers, and two colliers, making a total of 370 ships, not counting repair vessels and store ships. But Congressional funding for this program was not always assured. Only a single battleship, instead of the planned two per year, had been laid down in 1913 (the U.S.S. Pennsylvania) and 1914 (the U.S.S. Arizona). The General Board repeatedly called for more scout

cruisers, only to find that Congress preferred battleships and destroyers. Consequently, the navy was far from its goals when war broke out.

The war in Europe made War Plan BLACK highly unrealistic. That plan anticipated the American fleet operating from an advanced base at Culebra, Puerto Rico -- presumed to be a German objective -- meeting a German invasion force attempting to seize an island in the West Indies. While Culebra had indeed been an objective in German war planning in the event of conflict with the United States, such action became less

likely once Germany was at war with Great Britain.

The outbreak of war in Europe saw increasing emphasis on "preparedness," culminating in the Naval Act of August 1916, just two and one-half months after the Battle of Jutland. The Act authorized the laying down of ten battleships and six battlecruisers over a three-year period. The battleships were to be as large or larger than any foreign equivalent: the first four, the Colorado-class, to be of 32,000 tons with eight sixteen-inch guns; the next six, the South Dakota-class, to

be 42,000 tons with twelve sixteen-inch guns. The capital ships were to be supported by ten scout cruisers, fifty destroyers, nine fleet-type submarines, and sixty-seven coastal defense submarines. The construction was to commence by July 1919 and be completed by 1922 or 1923.

This program, though, was not specifically aimed at American intervention in the war. It reflected, rather, the desire to be ready for any and all eventualities whatever the outcome of the war, to include a hostile coalition led by Germany in the Atlantic and Japan in

the Pacific. The navy had to be ready to fight in the Caribbean, the Pacific, or, in the worst case, in both at once. The result was a planned fleet top heavy in capital ships, even though the Battle of Jutland had sent mixed signals regarding the role of capital ships in

future war. And the naval war in Europe was demonstrating the need for smaller ships to counter the submarine threat.

Admiral Sims |

The eventual American intervention in the war came in April 1917, in part as a response to German resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. April 1917 was the worst month of the war for the Allies with respect to losses from submarines. Had that rate of sinking

continued, it is possible that the Allies might have lost the war. This fact was made clear to Rear Admiral William Sims, president of the Naval War College, who had been ordered to Britain to liaison with the

Admiralty on the eve of America's entry into the war. In fact, the ship he traveled on, the American Line's New York, had been damaged by a submarine-laid mine approaching Liverpool. When Sims met with his counterparts at the Admiralty, the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, was shockingly frank about the crisis. The Admiralty, in desperation, was being forced to implement the convoy system. This, though, was easier said than done, for it could only be commenced

gradually and required large numbers of smaller ships -- primarily destroyers -- as escorts. While an erroneous overestimation of the number of escorts required had been one of the reasons for delaying implementation, there was still a considerable shortfall.

The Admiralty said they needed thirty-two additional destroyers to begin convoying inbound traffic in the North and South Atlantic.

Sims, who was subsequently named commander of U.S. naval forces in European waters, was an early advocate of the convoy system. On 14 April, he cabled Washington his recommendations that the maximum

number of American destroyers be made available at once. Sims argued that the timely arrival of even a modest number at this critical moment of the war might exert some strategic leverage, given the fact that

it would take time for the United States to mobilize sufficient military resources to have any impact on the war. The destroyers could work out of Queenstown, on the southern coast of Ireland, with an additional advanced base at Berehaven (Bantry Bay). Sims recommended that the destroyers be accompanied by other antisubmarine craft, support and repair ships, and the staff to man the bases. He added further recommendations that were less welcome in Washington, even if they were patently obvious. Under the present circumstances, he claimed, American battleships would have little effect. And naval resources should not be held back, he said, to counter possible German

submarine activity in the Western Atlantic. Any such activity was likely to be little more than minor raids intended to influence public opinion and divert resources.

The initial, limited response of the Navy Department was to order Commander Joseph Taussig and six destroyers from the Eighth Division, Destroyer Force, Atlantic Fleet, to Europe. Taussig, in the U.S.S. Wadsworth, led Davis, Conyngham, McDougal, Wainwright, and Porter into Queenstown on 4 May, an event commemorated in the well-known painting by Bernard Gribble, "The Return of the Mayflower." [Above] The omens were good. Taussig found a personal letter of welcome from the First Sea Lord awaiting him. The two had met in China in 1900 during the Boxer Rebellion. Taussig also made a good first impression

on the British commander-in-chief at Queenstown, the redoubtable Admiral Sir Louis Bayly, reputed to be one of the most ferocious characters in the Royal Navy. When asked how long it would take his storm-battered destroyers to be ready, Taussig reportedly answered:

"We are ready now, sir, that is as soon as we finish

refueling. Of course, you know how destroyers are always wanting something done to them. But this is war, and we are ready to make the best of things and go to sea immediately." In fact, his destroyers had a long list of defects. Bayly allowed them four days to be fitted with depth charges and have the topmasts lowered to reduce visibility.

Six destroyers, however welcome, were not enough to turn the tide. Sims, supported by the American ambassador in London, asked for more. Similar requests were made by the Admiralty through the British mission in Washington. There were fifty-one modern destroyers in the American fleet, but Sims and the British had to counter strong reservations about stripping the United States of its destroyer force.

Admiral William Benson, Chief of Naval Operations, was not an admirer of the British. The admittedly Anglophile Sims suffered from the charge that he was too much under the influence of too much under the influence of the English. In fact, Benson had warned Sims before his departure: "Don't let the British pull the wool over your eyes. It is none of our business pulling their chestnuts out of the fire. We would as soon fight the British as the Germans."

Benson was certainly aware of the immediate crisis and of the

necessity to support the antisubmarine campaign, but he had his

eye on the future as well. A memorandum prepared by his staff in

February 1917 concluded:

"Vessels should be built not only to meet present conditions but

conditions that may come after the present phase of the world war...

We may expect the future to give us more potential enemies than potential friends so that our safety must lie in our own resources."

The General Board recommended: "Keep constantly in view the possibility of the United States being in the not distant future compelled to conduct a war single-handed against some of the belligerents, and steadily increase the ships of the fighting line, large as well as small, but doing this with as little interference with the building of destroyers and other small craft for the Navy and cargo ships for the

Merchant Marine as possible."

In May, another two divisions of destroyers arrived with the destroyer tender U.S.S. Melville, designated flagship of the force. In early June yet another destroyer division arrived along with a second tender, the U.S.S. Dixie. By the end of the month, twenty-eight American destroyers were escorting convoys, rather than simply conducting patrols as had been the original plan. The Admiralty had

gone fully to the convoy system. The Navy Department was somewhat reluctant to follow suit. Benson and Secretary of the Navy Josephus

Daniels put more emphasis on armed merchant ships sailing independently, at one point even suggesting the already discredited method of patrolled sea lanes. Yet, Daniels and Benson continued to send all available destroyers; by the end of August, the number at Queenstown had risen to thirty-five.

The results shown by the convoy system brought the Americans around. After considerable internal debate, in which the now-converted

Benson reportedly "went to the mat," the American naval building priorities were changed. On 21 July 1917, Secretary Daniels ordered construction of new battleships to cease. Priority was to be given to

destroyers and other anti-submarine craft. He authorized construction of what would eventually total 266 destroyers. A reluctant General Board grudgingly admitted that some change in emphasis was required,

but reiterated that the battleship was still the principal factor of sea power and warned that a new realignment of powers after the war must not find the U.S. fleet unprepared to face possible enemies in the Atlantic or Pacific.

US Destroyer at Queenstown, Ireland

Once the yards were ready, procedures established, materials assembled or prefabricated, destroyer construction could be rapid. The record was set by the Mare Island Navy Yard, where the U.S.S. Ward was

launched 1 June 1918, just seventeen days after the keel was laid. She was commissioned less than two months later. This was, however, something of a stunt; most destroyer construction took two to three times longer. Nevertheless, the rapid pace ensured that many of these mass-produced destroyers suffered defects such as leaky seams and loose rivets. Only a few of the newly authorized destroyers, the 1,090-ton "flush deckers" of the Wickes and Clemson classes, were completed before the end of the war.

The same was true of the 500-ton "Eagle" class of patrol boats, "Ford boats," built at shipyards on the Great Lakes in assembly line fashion by the Ford Motor Company. One hundred twelve were ordered

(including twelve for Italy that were never delivered); only sixty were completed and most of those were after the war. Orders for the rest were canceled. A significant portion of the anti-submarine war was actually carried out by improvised craft: gunboats, converted yachts, Coast Guard cutters, and old cruisers.

The emphasis on construction of destroyers and other anti-submarine craft had another disadvantage. The navy had only a handful of what might be considered modern, fast scout cruisers, a class of warship that had repeatedly proven its value during the war. The first of the Omaha-class, authorized in the 1916 program, would not even be laid down until after the Armistice. Had the United States fleet been forced to fight a major naval action on its own, the absence of those cruisers would have been significant.

The first experimental convoy sailed from Hampton Roads on 24 May 1917, with a British armored cruiser as escort. When that proved successful, the Admiralty instituted regular convoys out of Hampton Roads every four days beginning in mid-June. By July, the convoy

system had been extended to ships sailing out of other Canadian and American ports, to include New York. The U.S. Navy provided older cruisers as escorts, not likely to have lasted long in a battle like Jutland but considered powerful enough to deter most potential

raiders. But the cruisers themselves were likely targets for submarines, so it was necessary for destroyers to meet the inbound convoys once they reached the danger zone just to the west of Ireland. This was the primary duty of the American destroyers at Queenstown.

By 1918, "fast" convoys, thirteen knots or so, mixed troopships and cargo ships, were escorted by armored cruisers or pre-dreadnought battleships, sailing out of Halifax and New York. Beginning in April, the buildup of American forces in France necessitated convoys

directly from New York to French ports on the Bay of Biscay. The French navy provided some of these with escorts of old armored cruisers. Most convoys, though, were operated and escorted by the Royal Navy.

According to a report prepared in August of 1918 for the Naval Committee of Congress, the Royal Navy provided destroyers for seventy percent of convoys, the U.S. Navy, twenty-seven percent, and the French

navy, three percent. Of the cruisers escorting convoys mid-ocean, sixty-one percent were British, thirty-five percent American, and four percent French.

The British also took the lead in plotting likely locations and operational areas of German submarines, using intelligence gathered through wireless intercepts. The Convoy Section at the Admiralty worked in close liaison with the Ministry of Shipping to route convoys

away from suspected danger. The legendary decoding activities of "Room 40" reinforced the dominant position of the British, a fact not always acknowledged or appreciated by the Navy Department in Washington.

There remained a difference in emphasis between the British and Americans over the use of the destroyers. Daniels informed Sims in July 1917 that the "paramount duty" of the American destroyers at

Queenstown was the protection of American troop transports, not the convoys of supplies flowing to the United Kingdom. Everything, Daniels said, was to be secondary to ensuring sufficient escorts to protect the

troops. Benson, for his part, strongly opposed the use of American destroyers for any other duties, such as screening for the Grand Fleet. This remained something of an academic issue until 1918, when the

buildup of American forces in France forced Sims to act on Benson's preference for Brest as the primary base for the American destroyers. Up to this point, Brest had been a base for a small number of converted

yachts used for anti-submarine patrols. The problem was that Brest did not have the facilities to serve as a major destroyer base. The American set to work in earnest, constructing fuel storage tanks and the rest of the necessary infrastructure. The expanded base, commanded initially by Rear Admiral William Fletcher, was later commanded by Rear Admiral Henry Wilson, with his flag on the destroyer tender, U.S.S

Prometheus. By August 1918, the number of vessels operating out of Brest exceeded the numbers at Queenstown: twenty-four destroyers, two tenders, and three tugs at Queenstown; thirty-three destroyers, sixteen yachts, nine minesweepers, five tugs, and four repairs ships at Brest.

In August 1917, the United States Navy had also begun operating out of Gibraltar, at first just in the Atlantic approaches, but later in the Mediterranean itself. The force included three of the only modern scout cruisers -- the U.S.S. Birmingham, the U.S.S. Salem, and the U.S.S. Chester -- as well as a heterogeneous collection of five ancient Bainbridge-class destroyers sent from the Philippines via the Suez Canal, several gunboats, six Coast Guard cutters, and ten yachts. The American commander, the sharp tongued Rear Admiral Albert Niblack, described his command as "a lot of junk here that has to be continuously rebuilt to keep it going." With respect to the old

destroyers, he said: "Every time they go out I feel particularly anxious until they get in again." Two modern destroyers joined the command in the summer of 1918 along with the well equipped, and badly needed, repair ship, the U.S.S. Buffalo.

U-58 Surrenders

The American destroyers in European waters were only a part of the United States Navy's effort in the Great War, but they were the sharp end of the stick. It is the nature of anti-submarine warfare, though, that the destroyers never had a brilliant fleet action or a massed torpedo attack on the enemy battle line. Their war was, for the most part, one of boring and arduous patrols, often in terrible weather, with little to show for the effort. There were a few actions, however, that showed tangible results, although only one enemy submarine can be attributed with certainty to the American destroyers. This was on 17 November 1917 off the south coast of Ireland, when the U.S.S. Fanning, assisted by the U.S.S. Nicholson, forced the U-58 to the surface with depth charges; the German submarine surrendered, but was then scuttled by her crew. There was also danger. The next month, the U.S.S. Jacob Jones was torpedoed and sunk of the Scilly Islands. The number of confirmed "kills" is misleading, though. While Admiral Sims signaled Fanning to "Go out and do it again," the primary mission of the destroyers was not to sink submarines, but to protect and escort convoys. Although not everyone admitted it, it was when nothing happened that the mission was

most successful. The safe arrival of the freighters and transports, with supplies and men, meant, in the long run, the defeat of the U-boats and of Germany.

The navy employed another type of anti-submarine craft from which much was expected. These were the seventy-ton, 110-foot wooden-hulled patrol boats with the evocative name of "submarine chasers." Outfitted with gasoline engines, they were armed with a single three-inch gun and a small number of depth charges. No fewer than 448 were ordered. Seventy-two were sent to Europe, equally divided between Plymouth and the Straits of Otranto in the Mediterranean. The French navy purchased fifty in 1917 and another fifty in 1918. But they

never really fulfilled the hopes placed on them. They were too slow and too small to escort convoys, and, while able to withstand rough weather, could not make much headway in heavy seas. The gasoline fuel made them prone to fires. Admiral Sims admitted to a French officer that the United States was using them simply "because we have them." They had been designed before the difficulties of anti-submarine warfare were fully realized. On the other hand, the relatively unsophisticated nature of the boats made them well suited for amateur crews, called up for service from the Naval Reserve. Those deployed at Otranto had a high proportion of college men and were dubbed the "Harvard-Yale Squadron."

The little boats worked in groups of three or four to

exploit what was thought to be a war-winning invention, the hydrophone. It was believed, perhaps correctly, that the American listening devices were superior to

anything developed by the Allies. In order to function

effectively, the hydrophones required silence, with

nearby ships stopping their engines so a submarine

might be detected. Three of the "chasers" would then

supposedly locate the enemy submarine by "triangulation." Another "chaser," or preferably a destroyer with

more offensive firepower, would be on hand for the

"kill." Their use in this manner conformed to Benson's

desire that they act "offensively." But the commander

at Otranto reported to Sims: "It has been very difficult

to induce people to believe the safety of their vessels

was enhanced by stopping them for set periods in

waters traversed by enemy submarines." The little

"chasers" at Otranto conducted thirty-seven submarine

hunts and believed they had made nineteen "kills." In

fact, none could be confirmed.

US Sub Chaser

The U.S. Navy also tried using submarines in anti-submarine operations, although American submarines,

in 1917, did not enjoy a great reputation for reliability.

A force of seven L-class submarines, supported by a

tug and a tender, operated out of Berehaven. Another

force of four smaller and older K-class boats conducted operations from a base in the Azores. Neither group had any success.

The much feared German submarine offensive in

the Western Atlantic finally occurred between May and

November 1918. Germany had developed large cruiser U-boats suitable for extended operations; six operated off the coast of America during this period. They

sank ninety-three ships totaling some 166,907 tons,

more than half of them American-flagged. Many of

those lost, though, were sailing vessels or smaller fishing craft. The most spectacular German success was

the armored cruiser U.S.S. San Diego, sunk by a submarine-laid mine on 19 July off Fire Island. This was

the largest American warship lost during the war.

German operations off the coast did not deflect

American political and naval leadership from the correct naval strategy. Forces were not recalled from

European waters, the vital convoys cintinued to sail

with great regularity, convoy losses were small, and the

German campaign failed. Naturally, though, the U.S.

Navy had to take defensive measures in home waters.

Coastal shipping was placed under the authority of the

appropriate East Coast naval districts. On 3 June,

Benson ordered coastal shipping to institute convoys

between Rhode Island, the eastern tip of Long Island,

and Cape Hatteras. Elsewhere, shipping was directed

to hug the coast. A thwteen night blackout of New York

City in June was eventually canceled when it was

determined that the darkened area made an even

greater contrast with the surrounding lights. A "naval

hunt squadron" consisting of a destroyer and six of the

little submarine chasers was established at Norfolk.

Another force was formed at Key West, ready to escort

convoys in the Gulf of Mexico should that prove necessary. Naval aircraft and dirigible patrols increased. Submarines were also used, sometimes working in

concert with the submarine chasers. Decoy vessels, an

American version of the British Q-ships, were

employed. None of these measures claimed a single

enemy U-boat, but the final judgment should rest on

the impact they had on the German submarines and the

potential reduction in shipping losses.

Not all United States Navy operations in the Great

War were conducted by small ships. In December

1917, the dreadnoughts of Battleship Division Nine of

the Atlantic Fleet, under the command of Rear Admiral

Hugh Rodman, arrived in Scapa Flow to become the

Sixth Battle Squadron of Admiral David Beatty's

Grand Fleet. The U.S.S. New York (Rodman's flagship), the U.S.S. Delaware, the U.S.S. Wyoming, and

the U.S.S. Florida,, followed by the U.S.S. Texas in

February, were all coal burners, at British request,

since Britain had ample coal while precious fuel oil

had to be imported through submarine infested waters.

The Royal Navy had first requested the reinforcement

in July, after they had to take five older pre-dreadnoughts out of commission in order to provide officers

and ratings for the new light cruisers, destroyers, and

submarines entering service. Admiral Benson's immediate response had been in strict Mahanian terms,

opposing any division of the American fleet: "The

strategic situation necessitates keeping the battleship

force concentrated, and cannot therefore consider the

suggestion of sending part of it across. The logistics of

the situation would prevent the entire force going over,

except in case of extreme necessity." He eventually

changed his mind after a visit to Europe. There were a

number of valid reasons: morale, prestige, training

opportunities, the possibility of influencing strategy,

and, perhaps most important, "a decision now averse to

sending any of our battleships to the front will be

invoked in the future against the building of large vessels." The Lansing-Ishii diplomatic agreement with

Japan also relieved some American concerns in the

Pacific.

It is one thing to shift ships from one fleet to another; it is quite a different matter to make them effective

members of the same team. The American dreadnoughts with the Grand Fleet had to adopt British

methods of signaling and maneuver. American gunnery was comparatively poor; it took months of training before the standard was comparable to that of the

Royal Navy. Beatty and Rodman worked well together, though. They made a conscious effort to do so.

Beatty kept his doubts to himself. Nonetheless, on

12 June 1918, a half year after the American arrival,

the Deputy Chief of Naval Staff at the Admiralty quoted Beatty

in a memorandum considering the American battleships "rather as an

incubus to the Grand Fleet than otherwise. They have not even yet

been assimilated to a sufficient degree to be considered equivalent to

British dreadnoughts, yet for political purposes he does not care that the Grand Fleet should go to sea without them." Beatty's views are disconcerting. Two months earlier, Admiral Rodman's squadron had been detached to provide cover for the Scandinavian convoy which ran between

the Shetland Islands and Norway. Twice during the preceding autumn, the convoy had been attacked by German surface warships and the Royal Navy had been forced to commit heavier ships as escort. This might

have provided the opportunity the Germans always dreamed of, catching a portion of the Grand Fleet with the entire High Seas Fleet. The Germans actually planned an operation of this sort for 24 April, but, due

to faulty intelligence, missed the convoy. The American squadron was covering the convoy from 16 to 18 April and thus missed stumbling onto the entire High Seas Fleet by a week. The outcome might have

been disastrous.

US Battleships

Another division of American battleships arrived in

British waters at the end of August 1918, Battleship

Division Six, commanded by Rear Admiral Thomas

Rodgers. Consisting of the newer oil-burners, the

U.S.S. Nevada, the U.S.S. Oklahoma, and the U.S.S.

Utah, accompanied by an oiler and a tug, they were

stationed at Berehaven to provide cover for regular

escorts accompanying the troop convoys now pouring

across the Atlantic. The Germans never tried a surface

attack on the convoys, and Battleship Division Six sortied only once, in October, on a false report.

The U.S. Naval Air Service, too, played their part.

When the United States entered the war, the Air

Service numbered only forty-eight officers and 239

enlisted men, with fifty-four training aircraft and a single naval air station at Pensacola, Florida. Training

quickly expanded and by June contracts had been let to

establish coastal patrol stations at Montauk Point,

Rockaway Beach, and Bay Shore, all on Long Island.

The first contingent of seven navy pilots and 122

mechanics arrived in France that same month, reportedly the first military unit to arrive overseas. They had

no aircraft of their own and depended on the French for

training and almost everything else. Eventually, the

Naval Air Service would have six seaplane stations in

France plus two in the Adriatic, four seaplane bases

and a kite balloon station in Ireland, and the strategically vital Killingholme Air Station near the mouth of

the Humber in England. At the time of the Armistice,

a large assembly and repair base was under construction at Pauillac near Bordeaux.

Operations began in July 1918; within two months

the Americans had forty-six aircraft on regular patrols

in the North Sea, supported by some 1,900 men. In

addition to the patrols, the "Northern Bombing Group"

began operations in the late summer of 1918. This

force, consisting of four squadrons of navy aircraft and

four of Marine Corps planes, was based near Calais

and Dunkirk. Its primary objectives were the German

submarine bases at Zeebrugge, Ostend, and Bruges.

Initial operations were delayed due to the late arrival of

aircraft. In fact, most had to be borrowed from the

British.

By the war's end, the Naval Air Service in Europe

had grown to 2,500 officers, 22,000 men, and over 400

aircraft. Including forces still in the United States,

where there were twelve operational bases and more

under construction, as well as bases in the Azores, the

Canal Zone, and Canada, the Naval Air Service had

6,716 officers and 30,693 enlisted men, and the Marine

Corps air component had 282 officers and 2,180 men.

Together, the two components of the navy had 2,107

aircraft, 15 airships, and 215 balloons.

In scale, the controversial "Northern Barrage" was

one of the largest American naval operations of the

war. The plan was pushed by the navy, although Sims

was opposed as it potentially diverted resources from

the vital convoys. The British were not enthusiastic;

Beatty, for one, feared it might hinder movement of the

Grand Fleet in the event of a German sortie. Once the

minelaying began, suspicions arose regarding the

effectiveness of the American mines. The British finally agreed to the project because they felt it was the only

way to gain unqualified American support for other

naval operations.

The plan was to lay a giant minefield extending from

the Orkneys to Norwegian territorial waters south of

Bergen, with the goal of preventing German submarines from getting out of the North Sea. The British

were responsible for the area farthest to the west, some

fifty miles of deep minefields supported by surface

patrols intended to force submarines to dive into those

mines. The British were also responsible for Area C,

the sector closest to Norway that could not be

patrolled; it consisted of deep and shallow minefields.

The American minelaying force, commanded by Rear

Admiral Joseph Strauss, was in charge of the largest

portion, the central sector consisting of 130 miles of

shallow minefields in three successive lines.

The United States had developed an "antenna-type"

mine, as opposed to the usual "contact" mine, and

eventually provided 56,611 of the 70,263 mines laid.

The American-built mines were loaded at a special

depot near the Norfolk Navy Yard onto Lake-class

freighters, which delivered them to ports on the west

coast of Scotland. They were then carried by rail or

canal to assembly points in Invergordon and Inverness

on the east coast. The actual minelaying was carried

out by Mine Squadron One of the Atlantic Fleet, under

the command of Captain Richard Belknap. The converted cruisers U.S.S. San Francisco and U.S.S.

Baltimore were capable of laying 5,500 mines every

four hours. They were supported by eight converted

coastal steamers. The British began laying mines in

the western sector in March 1918, but the Americans

were not ready to commence operations until June.

American capacity was so great, though, that they soon

joined the British in their zones. Just over a month

before the end of the war, the Norwegian government

consented to minelaying in their territorial waters, but

the war ended before any were laid. The operation cost

some forty million dollars and probably accounted for

no more than six or seven U-boats.

Once the Northern Barrage was completed, the navy

was anxious to employ its considerable resources and

capabilities elsewhere. The Americans proposed a

Sicily-Cape Bon minefield in the Mediterranean, but

this was rejected by the Allies in August. Agreement

was eventually reached on minefields in the Aegean

and Adriatic, with Bizerte as the base of operations.

This project, too, was just getting underway when the

war ended.

The United States Navy proposed other operations

in the Mediterranean as well, including Marine Corps

landings on the island of Curzola and the Sabbioncello

Peninsula in the Adriatic, and a raid by American predreadnought battleships on the Austrian naval base at

Cattaro. These came to nothing, as the proposals raised

difficult issues of command in the Mediterranean

which the Italians considered as within their purview.

The so-called "Atlantic Bridge" had delivered to

France, by August 1918, some 1.4 million American

troops, a considerable logistical achievement. Troop

transport was the responsibility of Rear Admiral Albert

Gleaves, commander of the Cruiser and Transport

Force. The Americans enjoyed a windfall at the declaration of war. Eighteen large German ships interned in

American ports were seized. These had the equivalent

of 304,270 tons and a carrying capacity of 68,600

troops at one time. Years of neglect, as well as some

sabotage by their German crews, delayed their entry

into service. The best known was probably the giant

Hamburg-Amerika Line's Vaterland which, as the

U.S.S. Leviathan, regularly carried more than 10,000

men each trip. Unfortunately, America had

lagged behind European contemporaries with regard to

large passenger liners suitable for trans-Atlantic transport. During the course of the war, over fifty percent

of all American troops were carried on British or

British-controlled vessels, with some carried on French

and Italian ships. After the Armistice, the navy had to

use pre-dreadnought battleships and armored cruisers

to repatriate many of the American troops.

Conveyance of troops was only part of the story.

Their logistical needs had to be met and this required

huge amounts of shipping. The number of cargo ships

and transports under navy control grew. On 9 January

1918, the Naval Overseas Transport Service was established. At its peak, it operated 378 ships with a carrying capacity of 2,397,578 tons. By the Armistice, the

Service controlled some 450 ships and was in the

process of taking over another one hundred.

US Shipbuilding Poster |

American civilian shipping capacity played its part.

The Federal Shipping Act of September 1916 had created the United States Shipping Board with Edward

Hurley as chairman, intended "to create a merchant

marine to meet the requirements of the United States."

After the entry into the war, the United States Shipping

Board Emergency Fleet Corporation was formed to

acquire, build, and operate merchant ships. This body

was eventually responsible for over two thousand

ships. New shipyards were authorized, to be built by

private firms. Ship construction was simplified

through standardized designs and "fabricated" construction techniques. The three biggest companies, the

American International Corporation, the Submarine

Boat Company, and Merchants Shipbuilding, were

authorized to cooperate to avoid wasteful competition

for materials and resources which might drive up

prices and delay construction.

The best known of these shipyards was perhaps the

American International facility on Hog Island at the

junction of the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers near

Philadelphia. The standard 7,500 ton ships built there

were known as "Hog Islanders." The massive shipyard

had fifty slips, plus outfitting berths that could accommodate twenty-eight ships. Much of this, however,

was capacity for the future. Of the 122 "Hog

Islanders" built, only twelve were launched in 1918

and none were truly in service before the Armistice.

Another standardized design was the Lake-class, so

named because they were built at yards along the Great

Lakes. Relatively small at 2,300 gross tons, they were

designed to pass through the locks of the Welland

Canal at Niagara Falls. Sixty-eight were eventually

operated by the Naval Overseas Transportation

Service.

The United States Navy finished the World War

doing a very different mission than anticipated.

Instead of a Mahanian battle fleet engaged in a control

of the sea conflict with an enemy fleet, the navy essentially functioned as a transport and escort force. The

rapid expansion caused considerable strain in terms of

personnel and training. Taussig reported an almost

constant turnover in the personnel of his destroyers at

Queenstown to provide cadres and crews for ships

being commissioned at home. The United States Navy

was just getting up to steam when the war ended. It

had not truly shown its full potential, although the huge

construction programs would likely have paid great

dividends had the war gone on into 1919 or 1920 as

expected. The full potential of the United States Navy

would have to wait until the next world war.

From: American

Armies and Battlefields in Europe

Return to Relevance Main Page

Comments on these pages may be directed to:

Michael E. Hanlon (medwardh@hotmail.com) regarding content,

Original artwork © 1996-2005 The Great War Society

|

|