January

2020 |

|

|

|

Burying the War's Dead

The Return of Private Davis from the Argonne

by John Steuart Curry

(Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX)

Honoring the Fallen

In 1919 the men who served in uniform and who died in the war were not yet looked upon as slaughtered sheep or victims of some evil betrayal by their elders. That reaction to the war was still bubbling below the surface but had not yet gushed into the opem. The dead soldiers were still fallen heroes who had answered the call of duty and had faced a great trial on behalf of their families and countrymen. Governments, of course, encouraged this view–they needed to gloss over the fact that it was their decisions that started the war, kept it going for four years, and resulted in millions of deaths. The political class might lose their legitimacy if was widely understood that their stupendous mistakes had slaughtered a generation. Churches, also, fully supported a "Sacrifice and Remembrance" narrative. They were uncomfortable at explaining why so many Christians had been quite so ready to kill other Christians. Furthermore, the surviving veterans and families of the deceased wanted their comrades and sons to be treated respectfully. In this issue of the Trip-Wire, we are going to look at the short period at war's end, when all the combatants and all the major factions within each country were in accord on what was to be the concluding act of the Great War. Except in Russia where the Soviets had seized power, the fallen of all nations would be treated respectfully and honored with beautiful burial sites and memorials on all the major battlefields. It was a remarkable international achievement, even if the motives behind it were not entirely candid. MH

Caring for the Dead During the War

Chaplain of the U.S. 33rd Division Identifying the Dead

By Colin Baker and Lynn Rainville

The soldiers who died during combat posed an

ethical dilemma for their surviving comrades: how to safely and

properly care for their corporeal remains while fighting for one’s

life? During World War I, temporary burial sites were created that

ranged from hastily dug, individual burials to mass graves. Various

military units were responsible for managing these temporary

resting places, including sanitary squads and the Pioneer Infantry.

Military chaplains played an important role in presiding over the

funerals for the individuals buried in these impermanent graves. The mass casualties of trench warfare often dictated that

chaplains had to bury the dead immediately in the vicinity of the

front line, occasionally even under fire. Twenty-three U.S. Army

chaplains died during World War I. Several are buried at the

Meuse-Argonne cemetery. Many demonstrated tremendous

bravery under fire administering last rites to fallen soldiers,

oblivious to the fire around them, or dashing out into the open to

rescue the wounded without regard for their own lives.

From the military standpoint, identification and burial were matters

of both accounting and morale. Nothing was more depressing to

the front line soldier than to see unburied dead around them.

For civilians, there was a new human need that diverged from the

earlier practice of mass anonymous burials for lower ranks.

Because mass “death at a distance” was so traumatic, the public

demanded “rights” to recover and identify the body. Families

required an individual body or grave as a focus of their grief.

Burial Detail at a French Cemetery

Burial detail, often performed by specialized units, notably African

American in the U.S. Army, was among the most unpleasant and

unpopular tasks of the war. Burial groups were supplied with

rubber gloves, shovels, stakes to mark the location of graves,

canvas, and ropes to tie up remains amongst other tools and

materials. Men remarked that it was “the most dreadful experience

I’ve ever had.” One chaplain assigned to this detail described the

post-traumatic effects of such work as causing a trying “of the

nerves…and a curious kind of irritability that was quite

infectious”

After the war ended the first burial task was to consolidate

thousands of isolated graves, next to combine small cemeteries

into larger ones, and finally to locate and identify the large numbers of the missing at cemeteries. Only after this process, in

the 1920s, did the re-interment into large permanent cemeteries such as the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery at Romagne, become feasible.

When hostilities ended, the Americans and their allies had to decide how and where to bury their dead. Mass graves had been

commonly used in past conflicts, such as the 6,000 British soldier

deaths from cholera during the Crimean War. One could argue

that the American ethic of individualism influenced the decision to

bury each soldier under a named headstone whenever possible.

Moreover, the American ethos of democracy led to the historically

unusual circumstances of egalitarian cemetery plots where

majors were buried alongside privates. In Europe, America

negotiated the long-term lease of hundreds of acres of land in

order to bury their dead in "American cemeteries." After World

War I, the Americans laid out eight cemeteries along the former

"Western Front."

Source: American Battle Monuments Commission, "Teaching with the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery"

A Very British Solution

Detail, Lone Tree CWGC Cemetery, Ypres Salient

For the important work of memorializing the British Empire’s war dead, the Imperial War Graves Commission (now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission [CWGC]) employed luminaries of architecture, landscape, and

literature: Sir Herbert Baker, Sir Reginald Blomfield, and Sir Edwin Lutyens to

design the monuments, with typeface designed by Max Gill; Gertrude Jekyll to

oversee the landscape design, and Rudyard Kipling to choose the inscriptions. Because of the popularity of gardening in Great Britain, and even among the troops themselves, a general design guideline was that the cemeteries should remind visitors of an English country garden. In an interesting contrast, German landscape architects selected a more somber forest-like theme. [Examples shown below.]

War Graves Commission cemeteries are not identical, but they have certain

features in common. Most have stone enclosing walls and wrought-iron gates,

and all feature standard headstones. Cemeteries with more than 40 graves

generally have a Cross of Sacrifice as a focal point. Designed by Sir Reginald

Blomfield, the Cross of Sacrifice is a granite cross with a bronze sword embedded

on the front, mounted on an octagonal base.

Serre Road #2 CWGC Cemetery, Somme Battlefield

Cross of Sacrifice to Left, Stone of Remembrance to Right

Larger cemeteries, generally those with over a thousand graves (though there are

exceptions), also have a Stone of Remembrance, designed by

Sir Edwin Lutyens. Devoid of overt religious symbolism, the Stone recalls a tomb

or perhaps an altar. The gravestones themselves are of light-colored limestone

and differ only in their inscriptions. They generally feature an appropriate

religious symbol, a national emblem (in Canada’s case, a maple leaf) or

regimental badge, the soldier’s name, rank, unit, date of death, and age. Relatives

also had the opportunity to pay for a short epitaph or other inscription to be

added.

Around the periphery of many cemeteries overseas are graves marked “A

Soldier of the Great War/Known unto God.” The bodies of these soldiers were

unidentifiable. But though their graves do not identify them, the IWGC’S great

memorials to the missing ensure that their names are preserved.

Source: Manitoba Historical Society

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

|

|

National Efforts

Every major combatant in the Great War had a different approach to dealing with the remains of its fallen warriors. Here is a series of articles that looks at the specific policies and practices of different nations.

This Cemetery in Vosges Shows the Forest-Like Setting of Many German Cemeteries

History of the Commonwealth (Originally "Imperial") War Graves Commission

History of the Commonwealth (Originally "Imperial") War Graves Commission

The American Battle Monuments Commission

The American Battle Monuments Commission

Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge (German War Graves Commission)

Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge (German War Graves Commission)

Le Ministère des Pensions: French War Graves Agency

Le Ministère des Pensions: French War Graves Agency

Commissariato generale per le onoranze ai Caduti di guerra: Italian War Graves Commission

Commissariato generale per le onoranze ai Caduti di guerra: Italian War Graves Commission

Italian Monuments to the

Fallen of World War I (PDF)

Italian Monuments to the

Fallen of World War I (PDF)

Myth Making

Remembering the First

World War is remembering a series of

myths. They’re iconic in the sense that

they describe not just what happened

at a particular moment, but what

the rest of twentieth-century Europe

might become and did become. . . In February 1916, the

German army decided to push through French lines at Verdun.

In the course of the battle, stories turned into legend. One is the

Trench of the Bayonets. There were no trenches in the Battle of

Verdun; there were isolated pockets of men in big underground

forts, with artillery barrage going on day and night. Little pockets

of men would be caught in one part of the battle, and stayed put

to make sure the Germans would not get through. One group

was buried by a landslide. The weight of mud would move when

artillery hit a particularly wet part of the front. The German

platoon that took it left the bayonets sticking up out of the ground

to indicate where to find the dead. The French interpretation

was, “Here are fifteen French men who stood with their bayonets

until they were buried alive and they didn’t move an inch, ils

ne passeront pas (“they won’t get through”). This is a completely

made-up story, but it became a sacred site, commemorated every

22nd of February.

Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning, Jay Winter

America's Gold Star Mothers Pilgrimages

A Gold Star Mothers Group Arrives at Belleau Wood (Aisne-Marne) Cemetery

After families decided whether their lost members would be buried in Europe or repatriated home, about 33,000 Americans remained in the eight major U.S. cemeteries along the Western Front and England. In 1929 Congress enacted legislation that authorized the Secretary of War to arrange for pilgrimages to the European cemeteries "by mothers and widows of members of military and naval forces of the United States who died in the war. The Gold Star Pilgrimage provided the chance for 6,693 women who might otherwise not have been able to visit their loved ones' graves to travel to France.

The trips involved visits to Paris and a selection of the major American battlefields of the war. Each woman was escorted to the grave of her loved one. The army quartermaster corps managed the cemetery visits and very carefully planned the reception at the cemeteries. To make the visit as personal as possible, they did not permit any ceremonies but focused on each woman's visit. The cemetery superintendent gave each pilgrim a grave locator card, and the cemetery staff guided each woman to the grave. The guide then gave the woman flowers or a wreath to put on the grave and took a photograph.

Source: U.S. National Archives

The Last Love Battle

Remembering the First

“See that little stream — we could walk to it in two minutes. It took the British a month to walk to it – a whole empire walking very slowly, dying in front and pushing forward behind. And another empire walked very slowly backward a few inches a day, leaving the dead like a million bloody rugs. No Europeans will ever do that again in this generation.”

“Why, they’ve only just quit over in Turkey,” said Abe. “And in Morocco —”

“That’s different. This western-front business couldn’t be done again, not for a long time. The young men think they could do it but they couldn’t. They could fight the first Marne again but not this. This took religion and years of plenty and tremendous sureties and the exact relation that existed between the classes. The Russians and Italians weren’t any good on this front. You had to have a whole-souled sentimental equipment going back further than you could remember. You had to remember Christmas, and postcards of the Crown Prince and his fiancée, and little cafés in Valence and beer gardens in Unter den Linden and weddings at the mairie, and going to the Derby, and your grandfather’s whiskers.”

“General Grant invented this kind of battle at Petersburg in sixty-five.”

“No, he didn’t – he just invented mass butchery. This kind of battle was invented by Lewis Carroll and Jules Verne and whoever wrote Undine, and country deacons bowling and marraines in Marseilles and girls seduced in the back lanes of Wurtemburg and Westphalia. Why, this was a love battle – there was a century of middle-class love spent here. This was the last love battle.”

Tender Is the Night, F. Scott Fitzgerald

Doughboys in the Meuse-Argonne

Detail, Lost Battalion Memorial

Charlevaux Mill, France

From: Lost Battalion Tours / Rob Laplander & Mike Cunha Tour Leaders

When: 8-15 August 2020

Details: Download Flyer

HERE.

Mid Atlantic, League of WWI Aviation Historians

Chapter Meeting

When: 7 March 2020

Where: Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, near Dulles International Airport

Details: Download Flyer

HERE.

|

|

The Great War's Mass Burials

French National Cemetery and Douaumont Ossuary at Verdun

The American and British approaches to war burials were predicated on a tradition that demanded each fallen soldier was entitled to an individual resting place. Other nations, however, were inclined differently, especially regarding the unidentified individuals. In this article we look at the matter of mass burials.

Ossuaries, catacombs and charnel houses–crypts, chapels and caverns where human bones have been placed–are spread throughout Europe. Some are many hundreds of years old, others much more recent. As macabre as the idea may sound they are also a popular tourist attraction; the catacombs in Paris are perhaps the most well known and receive hundreds of thousands of visitors each year.

An ossuary is anything from a small box to a large building that contains human bones. A body is placed in a temporary grave, and then sometime later the bones are removed, cleaned, and placed in the ossuary–the final resting place. In many instances ossuaries were created as a solution to the lack of space in local cemeteries. Others, however, came about when human remains were recovered during the excavation of cemeteries–whether known or forgotten.

Ossuaries have a long history. The megalithic chambered tombs of the Neolithic and Bronze Ages are in all likelihood prehistoric antecedents of the more recent traditions we see in Europe. Three thousand years ago the ancient Persians, more specifically the Zoroastrians, placed the remains of their dead in a well or astudan–a literal translation being "the place for the bones".

Ossuaries are found throughout Europe, having been a common practice for both Catholic and Eastern Orthodox communities. There are chapels and crypts in churches and monasteries that house the bones of thousands of individuals. Caves, catacombs, and underground tunnels also make for ideal ossuaries. People were interred as and when they died, whereas some ossuaries are a kind of "mass grave," holding the bones of thousands of individuals who died as a result of anything from plagues to wars.

Turkish Mass Grave, Gallipoli Peninsula

Perhaps one of the most poignant ossuaries in Europe is the Douaumont Ossuary in northeastern France. Situated on what was the battlefield of the World War One Battle of Verdun and next to the largest French military cemetery relating to the First World War, the ossuary holds the remains of both French and German soldiers who fought in that horrific battle.

From 21 February to 19 December in 1916 over 230,000 French and German men died in what has been called L’Enfer de Verdun (Hell of Verdun). The bones from at least 130,000 unidentified soldiers have been placed in specially designed alcoves. Their names have been inscribed on the walls and vaulted ceiling of the ossuary. The adjacent cemetery has the identified remains of 16,142 French men. L’ossuaire de Douaumont was inaugurated by French President Albert Lebrun on 7 August in 1932.

Sacrario dei Caduti di Caporetto (Charnel House; Kobarid, Slovenia)

The most spectacular use of ossuaria for the burial of World War I soldiers was by the Italian Fascist government of Benito Mussolini. Once he came to power, his party looked upon itself as a sort of heir of the Great War's heritage and established a monopoly on commemorative monuments and burial sites for Italy's nearly 600,000 fallen. The theme for these new sites was not to be a sense of tragic sacrifice but one of the exaltations of a victorious nation. In 1920 the construction of the nation's first ossuary was started on Monte Pasubio, one of many spectacular mountain top battlefields of the war. However, the 19th-century look of the building did not meet the expectations of the Fascists when they took power. A new approach was needed. A spectacular series of ossuaria were built, right up to the eve of the Second World War.

Source: Archeology-Travel Website of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

Polish-Soviet War

Polish Machine Gun Position, August 1920

|

100 Years Ago:

Kaiser Wilhelm II Escapes Extradition and Prosecution

Kaiser Wilhelm in Better Days

|

Despite the British postwar election call to “Hang the Kaiser,” and the French prime minister Georges Clemenceau’s view that a trial of the Kaiser “would be one of the most imposing events in history, and that the conception was well worthy of being pursued,” Wilhelm II would never be arrested, tried, or sentenced. A Keystone Cops-style kidnapping organized by a U.S. Army Col. Luke Lea in January 1919 embarrassed the Allies, and any further unsanctioned efforts to apprehend the Kaiser were strongly discouraged. However, many of the Allied governments worked, mostly far behind the scenes, to find some quasi-legal way to pressure the Netherlands to hand over the world's most hated war refugee.

Nevertheless, on 23 January 1920 Dutch officials notified the Allies that they would not extradite the former Kaiser to be tried for war crimes. The late Norman Stone, however, wrote that Wilhelm got off lucky:

Having taken Germany into the First World War, he had fled at its end to Holland, where Queen Wilhelmina gallantly gave him sanctuary at a time when he might have faced extradition to a proto-Nuremberg. Other monarchs in exile had a very bad time of things–the last sultan was cheated by his landlady, the last Habsburg died in impoverished despair in Madeira–but Kaiser Wilhelm arrived in Holland with a massive train and seventy servants and had a substantial manor house at his disposal.

Queen Wilhelmina Protected the Kaiser

|

The republican governments of Germany not only allowed him a very large income but even in 1919, a supposedly revolutionary time, sent fifty-nine railway carriages of ‘priceless treasures’ from the various schlosses to join him in Holland. His family kept Cecilienhof, where the Potsdam Conference took place in 1945, a palace on Unter den Linden, another one in the Wilhelmstrasse and a great deal more. He was not grateful for any of this. When news came that republican ministers who had helped him had been murdered, he ordered champagne and did a little dance.

Having given him refuge, Queen Wilhelmina came under pressure from the Allies to extradite him. She refused, on the condition that he stay put on his Utrecht estate. The Kaiser found this "absolutely scandalous" and said he would ‘never’ forgive the queen. She owed him a great deal, he thought, because, after all, in 1914 his armies could have violated Dutch neutrality quite as much as Belgian had he ordered it.

Sources: Norman Stone in Inquiry and Allan Massie in Catholic Herald

|

The Fromelles Project

A Number of the Men Found Were from Company D, 31st AIF

In May 2008, after several years of painstaking research and investigation, a number of burial pits dating from the First World War were identified at Pheasant Wood, near Fromelles in northern France. In May 2009, archaeologists from Oxford Archaeology began to excavate the pits and by early September they had carefully removed the remains of 250 soldiers, mostly Australian, buried behind German lines after the Battle of Fromelles in July 1916. This discovery would lead to the eventual construction of the first Commonwealth cemetery to be constructed in over 50 years.

The battle of Fromelles was an Australian Imperial Force and British Army joint operation, fought on a 4,000-yard section of the German front line. It involved the British 61st and Australian 5th divisions, and, on the German side, the 6th Bavarian Reserve division. It was the first action that the Australian Imperial Force saw on the Western Front. The battle resulted in over 5,500 Australian and 1,500 British casualties, of which almost 2,000 Australian and over 500 British were fatalities. It was, and still is, the worst 24 hours in Australian military history.

Those who had fallen close to or in the German front line were gathered up by the enemy, and buried behind German lines in unmarked mass graves, including graves to the south of Pheasant Wood on the edge of Fromelles village. The graves went unrecognized for more than half a century until researchers, most notably retired Australian schoolteacher Lambis Englezos, identified them through historical research. When an evaluation confirmed their presence, the Australian and British governments announced a jointly funded program of excavation and recovery so that the soldiers could be reburied in individual graves.

A Casualty on the Fromelles Battlefield, July 1916

With an international team of forensic and investigative professionals, Oxford Archaeology began excavating and recovering the soldiers in May 2009. Unlike traditional archaeology, where the goal is largely scientific, this was a humanitarian project in which the sole focus was on the recovery and identification of individuals with living families using DNA. The graves, eight of them in total, were excavated over a period of four months. Soil was meticulously removed, first by a small mechanical digger, and then using specialist hand-tools, to expose individuals (all practically skeletonized) and artifacts. Teeth and bones were sampled for DNA, and all evidence was comprehensively recorded before being lifted and transported to the temporary mortuary. All the skeletons were in good or excellent condition, allowing a high level of biological and personal identification information to be obtained. As expected, the skeletons exhibited extensive wounding–blast, projectile, and sharp-force lesions were all recorded–from the battlefield.

As the project proceeded, construction began nearby in 2009 for a new burial site for the re-interment of the bodies in individual graves nearby just outside Fromelles. Named Pheasant Wood Cemetery, it was to be ready to receive burials by the beginning of 2010.

All the recovered evidence was collated into confidential case reports, one for each soldier, for the identification commission, which convened annually over five years, beginning in 2010. A data-analysis team collated this information with historical records, family trees, and DNA results from the deceased and their descendants. This was a fundamental part of the identification process, and employed a rigorous, repeatable methodology, free from bias and devised specifically for this project–the first attempt at historic identifications on a large scale.

The Last Burial at Pheasant Wood Cemetery, 19 July 1920

To date, a total of 166 Australian soldiers have been identified by name. Of the remaining 84 soldiers, 59 are considered to have served for the Australian Army, two for the British Army, and 23 remain "known unto God." [Statistics updated, 27 Dec. 19] While DNA has been a prime mover in these identifications, it has not been without its limitations. The use of DNA extracted from people who died almost 100 years ago can only use inherited markers associated with the maternal and paternal lines. This inevitably means lower levels of match probability compared with autosomal DNA analysis associated with modern--day scene-of-crime investigations.

The first and last burials to take place at Pheasant Wood Cemetery were marked by ceremonies held in January 2010 and on 19 July 2010. The latter ceremony was held on the 94th anniversary of the Battle of Fromelles, and was a dedication service when the last–as yet unidentified–soldier was reburied. A new museum of the Battle of Fromelles was opened in July 2014 adjacent.

Sources: World Archeology, 19 July 2019; CWGC; Wikipedia.

|

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications

|

Order Our

WWI Musical CD

Click on Image for Information

|

Shop at

Amazon.com

|

Order the Complete Collection

Over the Top Magazine

Click on Image for Information

|

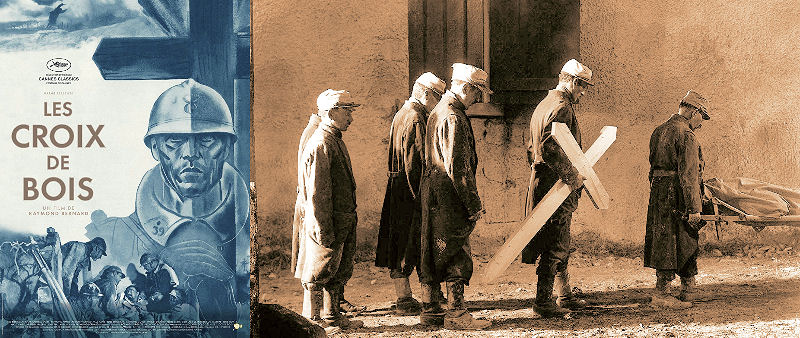

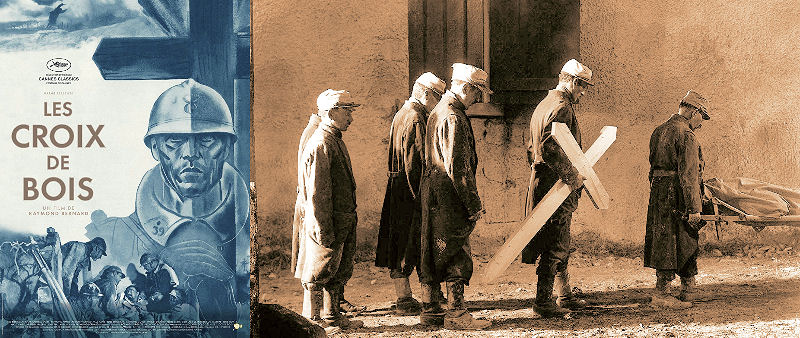

A World War One Film Classic

Wooden Crosses, or Les Croix de Bois (1932) in the original French, is considered by some critics to be the best of the anti-war films, such as The Big Parade or All Quiet on the Western Front produced in the interwar period. Its general plot is a Gallic version of All Quiet: a young idealistic volunteer–substitute French Gilbert Demachy (played by Pierre Blanchar) for Germany's Paul Bäumer–joins a veteran unit, bonds with his mates, fights in many actions that gradually kill off most of his friends in the company, and, in the last scene of the movie, dies.

There are, however, many touches to Wooden Crosses that set it apart from similar war films. Gilbert's unit, the 39th Regiment of Infantry, is deployed to the Champagne and all its combat sequences were filmed on location, in still existing wartime trenches that are recognizable because of the distinctive chalky-white soil of the region. Consequently, almost every scene in the movie passes the "authenticity test" discussed in last month's Trip-Wire. There are multiple intense dramatic set-ups, as well, throughout the movie. In one, the troops are asleep in a dugout when they hear digging underneath–the Germans are tunneling a mine to lay explosives directly below their position! Their superiors, however, order them to hold the position and some of the men are driven mad as the mine's detonation becomes more and more likely. Finally, Wooden Crosses features some of the most explicit and effective use of symbolism to reinforce its message I've ever seen. The cross as an icon of death appears in countless ways: burial parties carrying crosses pass nearby, some of the men attend mass in a nearby village, and countless cemeteries are worked in the action, including the most intense battle sequence of the movie. Available for purchase at Amazon and as a DVD rental from Netflix.

|

|

Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

(Or send it to a friend)

(Or send it to a friend)

|

Design by Shannon Niel

Content © Michael E. Hanlon

|