February

2020 |

|

|

|

The Armenian Genocide

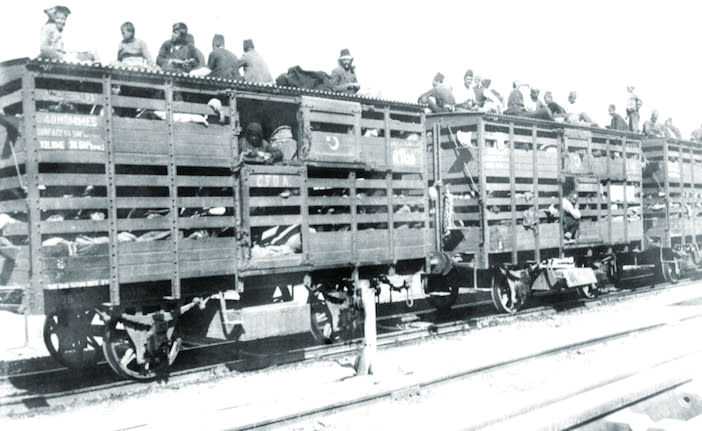

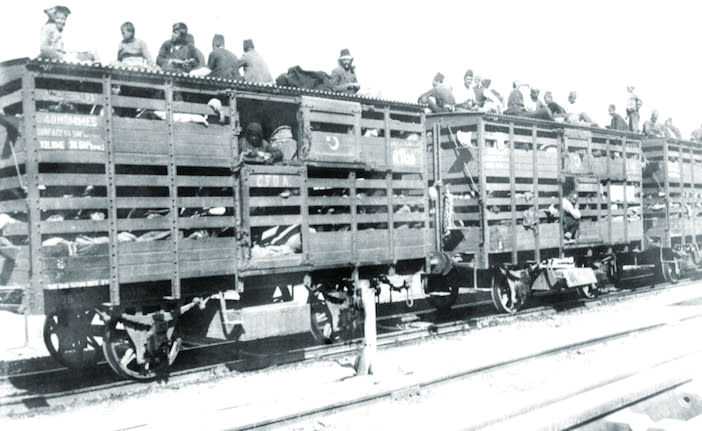

Deportation Column of Armenian Women and Children en route to Mesopotamia, 1915

The Armenian Genocide launched in 1915, was a matter of state policy,

approved by a governing triumvirate of Talaat, Enver,

and Jemal Pasha. Their guiding principle, which melded

ethnicity and nationalism, had always been "Turkey for

the Turks.” It was sometimes left unstated, but they

had always felt threatened by the empire's minorities,

even more so after they joined the Central Powers.

Armenians in the eastern provinces, where Armenian

communities existed on both sides of the Ottoman

border with the Russian Empire, were a double problem. When hostilities broke out in the region, many

Armenians supported the Russian enemy, which gave

the Young Turks an excuse, possibly one they had been

waiting for, to take decisive action.

The government began a well-coordinated propaganda

campaign to demonize the Armenians in the eyes of

their Turkish neighbors. Since literacy was very low in

1915 Turkey, the campaign was primarily by word of

mouth. According to historian Vahagan Dadrian, the

vilification of the Armenians was spread mainly

through sermons by mullahs and by town criers who

sprinkled the news about Armenians with words such

as "traitors," "saboteurs," "spies," "conspirators," and

"infidels."

Most sources agree that the genocide against the

Armenians began with the imprisonment and execution of 250 Armenian intellectuals in Constantinople on 24 April 1915, followed by a similar roundup in the

provinces. This left Armenians in every area without

leadership or spokesmen.

Railroads Were Incorporated into the Deportation Scheme

At about the same time, emergency legislation was passed. Conscription

allowed the rounding up of about 60,000 Armenian men, who were

put under military control, placed in labor battalions in

isolated areas, and simply worked to death. Meanwhile, those remaining–the young, the old, the infirm,

and the women–were left without the protection or

guidance of those men. Thus was launched the effort to rid Turkey of its

Armenian population.

Deportation would be the principal means of extermination.

People were moved en masse under such pretexts as

military necessity or reuniting families. Women, older

people, and children–the "deportees"–were force-marched in caravans into the desert. Virtually every

Armenian settlement in the empire was emptied out.

These deportations were actually death marches.

Supervising these convoys was a group called the

"Special Organization" that was directed by an

important member of the Central Committee, Dr.

Behaeddin Shakir. Shakir was very clear about his

mandate: "The Armenians, living in Turkey, will be

destroyed to the last. The government has been given

ample authority. As to the organization of the mass

murder, the government will provide the necessary

explanations." MH

Prelude to Mass Murder

A Traditional Armenian Family from the Village of Patem (AMI Collection)

The Armenians are an ancient people that have lived on much of the same land for more than 2000

years. For some of that time, they ruled their own kingdom. During long periods of Armenian history,

however, they have been a subject population, ruled by others. By the 16th century the Armenians were

subjects of the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman sultan ruled not only as a monarch but also assumed the

title of Caliph–the official leader of the Islamic faithful.

Ottoman law conformed in many ways with

Islamic law and was overseen by the Sheikh-ul-Islam (a religious leader who was appointed by the

sultan). Christians and Jews, including Armenians, Bulgarians, Croatians, Greeks, Romanians, Serbs, and

others, were classified as dhimmi (protected non-Muslim subjects). The dhimmi were granted considerable religious freedom, but they were not subject to Islamic law and therefore were without equal legal

standing. Codes also prohibited non-Muslims from certain professions–including service in the

Ottoman army–and subjected them to additional taxes. Despite their second-class status, as the empire

prospered, the Armenians fared reasonably well. During the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire's

fortunes declined. The economy stagnated, and corruption was rampant. Life for Armenians and other

non-Muslims became progressively more difficult.

Source: Facing History

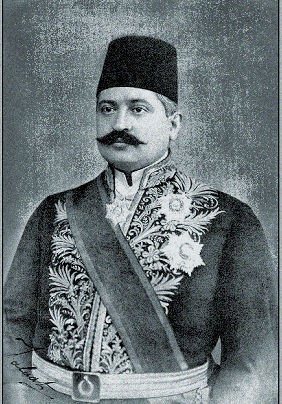

Organizers of the Crime

Young Turks Leadership Declares Revolution, 1908

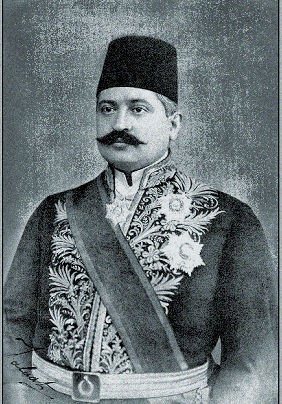

Talaat Pasha

(1874-1921)

|

According to the Armenian National Institute, the decision to carry out the extermination of Armenians within the old Ottoman Empire was initially made by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), popularly known as the Young Turks. The three dominant figures in the movement (known as the Three Pashas) were Mehmet Talaat, Minister of the Interior and eventually Grand Vizier, Ismail Enver, Minister of War, and Ahmed Jemal, Minister of Marine and Military Governor of Syria. Of the three, the minister most energized and most involved in prosecuting the anti-Armenian policy was Talaat Pasha. He had been the leading advocate for the Turkification of the Ottoman Empire from the birth of the CUP. As Interior Minister he had control of all the provincial officers and agents of the nation. A trained telegrapher, Talaat was able to keep his communications secret by circumventing normal governmental procedures. With the eventual defeat of Turkey in the war, Talaat fled to Berlin. Back home he was tried for war crimes by the new government, found guilty, and sentenced to death. He evaded execution because Germany refused to extradite him. However, he was discovered by an Armenian who had lost his family in the deportations and shot dead in Berlin in 1921.

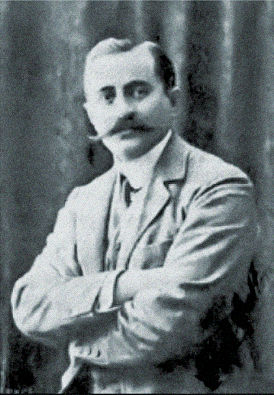

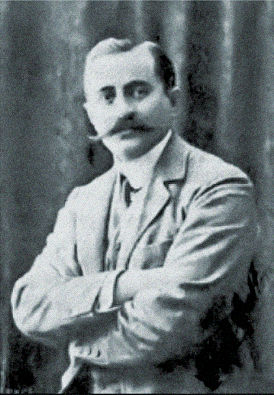

Behaeddin Shakir

(1874-1922)

|

The actual implementation of the extermination effort was placed in the hands of a secret group known as the Special Organization. They were in control of a vast network of administrators, military units, police, and propagandizers who were charged with planning, managing, and covering-up the massacres, deportations, and planned starvations. The bureaucratic genius in charge of the Special Organization was a physician/politician by the name Behaeddin Shakir. If Talaat could be considered the Heinrich Himmler of the Armenian Genocide, then Shakir might be thought of as the Adolph Eichmann. In one surviving document, Shakir inquired of a subordinate: “Are the Armenians being dispatched from there being liquidated? Are these troublesome people you say you’ve expelled and dispersed being exterminated or just deported? Answer explicitly.” In April 1922, Shakir, along with a former subordinate, Cemal Azmi, were killed on a Berlin Street, by Armenian assassins.

Sources: Wikipedia, Armenian National Institute

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

|

|

Different Perspectives

An event of such magnitude as the Armenian Genocide has many dimensions, so here I've tried to provide access to studies by parties with a variety of points of view on it.

1915: The Crumbling Of An Empire, And The Massacre That Ensued

1915: The Crumbling Of An Empire, And The Massacre That Ensued

The Republic of Turkey's Official Statement on the Allegation of Genocide

The Republic of Turkey's Official Statement on the Allegation of Genocide

Overview of the Armenian Genocide by Turkish/Dutch Scholar (PDF)

Overview of the Armenian Genocide by Turkish/Dutch Scholar (PDF)

Imperial Germany and the Armenian Genocide (PDF)

Imperial Germany and the Armenian Genocide (PDF)

Hero of the Genocide: Johannes Lepsius

Hero of the Genocide: Johannes Lepsius

The Three Pashas and the Armenian Genocide

The Three Pashas and the Armenian Genocide

Resistance and Rescue at Musa Dagh

Resistance and Rescue at Musa Dagh

Was It an Armenian or a Christian Genocide?

Was It an Armenian or a Christian Genocide?

Survivors' Stories

Survivors' Stories

Report from a German Observer

What is Germany's duty and, indeed, the duty of every civilized Christian nation in face of the Armenian massacres? We must try every means of saving the half-million of Armenian women and children who may still be alive in Turkey today, and who are abandoned to death by starvation, from an end which would be a disgrace to the whole civilized world. The hundreds of thousands of deported women and children who have been left lying on the borders of the Mesopotamian desert, and on the roads leading thither, can only maintain their miserable existence a short time longer. How long can people really support life by picking grains of corn out of horse-dung and depending for the rest upon grass? Months of insufficient nourishment and the prevailing dysentery will have brought countless numbers into a state past help. But at Konia a few thousand Armenians are still alive--educated people from Constantinople, who were in easy circumstances before their deportation, doctors, writers, merchants-and these could still be helped before they too succumb to the fate that threatens all.

There are 1,500 Armenians in good health-men, women and children, including grandmothers sixty years old and many children of six and seven who are still at work on a section of the Bagdad Railway between Eiran and Entilli, near the big tunnel, breaking stones and shoveling earth. For the moment they are being looked after by Herr Morf, Superintendent Engineer of the Bagdad Railway; but the Turkish Government has registered their names too. As soon as their work is finished, as it will be in perhaps two or three months' time from now, and they are no longer wanted, "new homes will be assigned to them,"-that is, the men will be taken off and slaughtered, the pretty women and girls will find their way into harems, the remainder will be driven hither and thither without food through the desert until all is over..

1917 Report, Dr. Martin Niepage, German Technical School at Aleppo

On the Scene: Ambassador Morgenthau

Some of the earliest reports of the atrocities came from the American ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Henry Morgenthau, Sr. As early as July 1915, he reported to the State Department: "It appears that a campaign of race extermination is in progress under a pretext of reprisal against rebellion."

Source: U.S. National Archives

A Conversation with Turkish Police Captain Shukri

As we rode our horses side by side, our conversation

about the deportations and massacres [continued,

and] I finally reached a point where I was no longer

able to restrain myself. Stiffened by this unfathomable

and crushing story, I turned to Shukri, who was relating

all this as if it were a children's fairy tale, and said, "But

Bey, you are an elderly Muslim. How did you have this

without feeling any remorse or guilt, when they were

neither conspirators nor rebels? Won't you remain

accountable for this innocent blood spilled, before

God, the Prophet [Muhammad], and your conscience?"

"Not at all," he replied. "On the contrary, I carried out

my sacred and holy obligation before God, my Prophet,

and my caliph. . .A jihad was proclaimed. . .The Sheikhul-Islam [the highest Sunni religious authority] had

issued a fatwa to annihilate the Armenians as traitors

to our state, and the caliph, in turn, ratifying this

fatwa, had ordered its execution. . . And I, as a military

officer, carried out the order of my king. . . Killing

people during war is not considered a crime now, is it?

Following this shameless and abhorrent statement, I

fell silent, because there was nothing I could say in

reply to an executioner who had likened the merciless

massacre of unarmed, defenseless women and infants

to killing people in war. In total, he was responsible for

the murder of 42,000 innocent people.

Armenian Golgotha, Grigoris Balakian

Doughboys in the Meuse-Argonne

Detail, Lost Battalion Memorial

Charlevaux Mill, France

From: Lost Battalion Tours / Rob Laplander & Mike Cunha, Tour Leaders

When: 8-15 August 2020

Details: Download Flyer

HERE.

Mid Atlantic, League of WWI Aviation Historians

Chapter Meeting

When: 7 March 2020

Where: Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, near Dulles International Airport

Details: Download Flyer

HERE.

|

|

Rationales for Genocide: Betrayal and Revolt

The Fate of Armenians Who Resisted, or Didn't Resist

The position of those who argue that punitive measures against its Armenian population by the Turkish government were (at least in part) justified is based on something of a one-sided interpretation of two historical events: the actions of Armenian citizens and expatriates who assisted and fought alongside Russian forces that invaded the nation between 1914 and 1917, and the taking advantage of the civil disorder caused by the war by Armenian independence groups to stage rebellions against the state. How much of this actually occurred? Such treasonous assistance to the enemy would have taken place on the little-known Caucasus Front, where Russian advanced units were deployed to engage opposing Ottoman units.

The Russian Caucasus Army crossed the frontier on 1 November in the Bergmann Offensive, capturing Koprukoy. Initially numbering 100,000 men, the army was reduced to 60,000 troops after almost half of the force was transferred to the Eastern Front following Russian defeats at Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes. Four volunteer units consisting of Russian Armenians, as well as detachments of Georgians and Caucasus Greeks, fought alongside the Russians. Shortly after, Turkish Commander Enver Pasha was able to outflank the Russians at Koprukoy and force them to abandon the city. This made him, however, disastrously over-confident.

On 2 January 1915, the Russians launched a counterattack at Sarikamis that cost the lives of 90,000 Turkish soldiers, including 53,000 who froze to death, and thousands more who died from typhus. Russian losses were placed at around 16,000 killed and wounded. Thoroughly outmaneuvered by his Russian rivals, Enver blamed the defeat on Armenian assistance to the Russians and desertions by his own Armenian soldiers. He quickly turned this into a pretext for the systematic cleansing of Turkey's Armenian population.

Armenian Irregulars Fighting with the Russian Army

Armed resistance by Armenians had pre-dated the Great War. At least back to the 19th century, there were armed Armenian civilians who voluntarily left their families to form self-defense units and irregular armed bands in reaction to the mass murder of Armenians and the pillage of Armenian villages by criminals, Kurdish gangs, and Turkish forces. While the defeat at Sarikamis is almost fully attributable to Enver's incompetence, the military assistance lent to the Russian cause–in the name of liberation or vengeance for past crimes–by the Armenian populations of both Russia and Turkey was substantial. Boghos Nubar, the president of the Armenian National Delegation in the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 later wrote:

In the Caucasus, where, without mentioning the 150,000 Armenians in the Imperial Russian Army, more than 40,000 of their volunteers helped to liberate part of the Armenian vilayets, and where, under the command of their leaders, Antranik and Nazerbekoff, they, alone among the peoples of the Caucasus, offered resistance to the Turkish armies.

Beginning in April 1915, the Ottoman authorities rounded up tens of thousands of Armenian men and had them shot. Hundreds of thousands of Armenian women and children were deported. Many Turkish historians have contended that these actions were a justified, or at least explicable, response to a serious threat to national security. They cite in particular the Armenian "revolt" that began in the heavily-Armenian city of Van in mountainous Anatolia on 20 April 1915. In fact, the "revolt" was a desperate response to the persecution already underway–by 19 April, 50,000 Armenians had already been killed in Van province, and tens of thousands were being deported from neighboring Erzerum, another largely Armenian Community.

Defenders of Van

The regional governor, Djevdet Bey, triggered the resistance in Van when he demanded the city provide 4,000 men for forced labor in military battalions and deployed troops to surround the city and execute some of the local Armenian leadership. Irregular units of Van's Armenian population, some with military experience, were organized as news spread of the massacres in the area and the mass murder of Armenian men who had been conscripted into the Ottoman Army. Secret appeals were sent to the Russian Army for relief. On 20 April they captured the Fortress of Van and held the city until Russian troops, accompanied by Russian-Armenian volunteers arrived on 18 May. Thousands of the defenders died from shelling, hand-to-hand fighting, and disease in the month of fighting.

The CUP declared the resistance at Van an uprising and it became an additional pretext for deportation. The defenders of Van desperately hoped that with Russian help they could take the offensive and save some of their countrymen in the neighboring regions. It was not to be. On 31 July, the Russians announced that they were leaving, and they ordered all Armenians in the Ottoman territories they had occupied to retreat to the Russian side of the border. The Armenians of Van were forced to abandon forever the homes they had fought so hard to defend and joined 270,000 other exiles in a month-long exodus across hostile territory to the Yerevan Plain. The city would change hands at least three times during the war. When the Turkish Army regained control of Van in 1918, all the Armenians who had returned after temporarily evacuating the city were slaughtered. Today Van remains within the borders of Turkey, with no discernible Armenian population.

Sources: The Near East Relief Historical Society; History.net; International Encyclopedia of the First World War; British National Archives

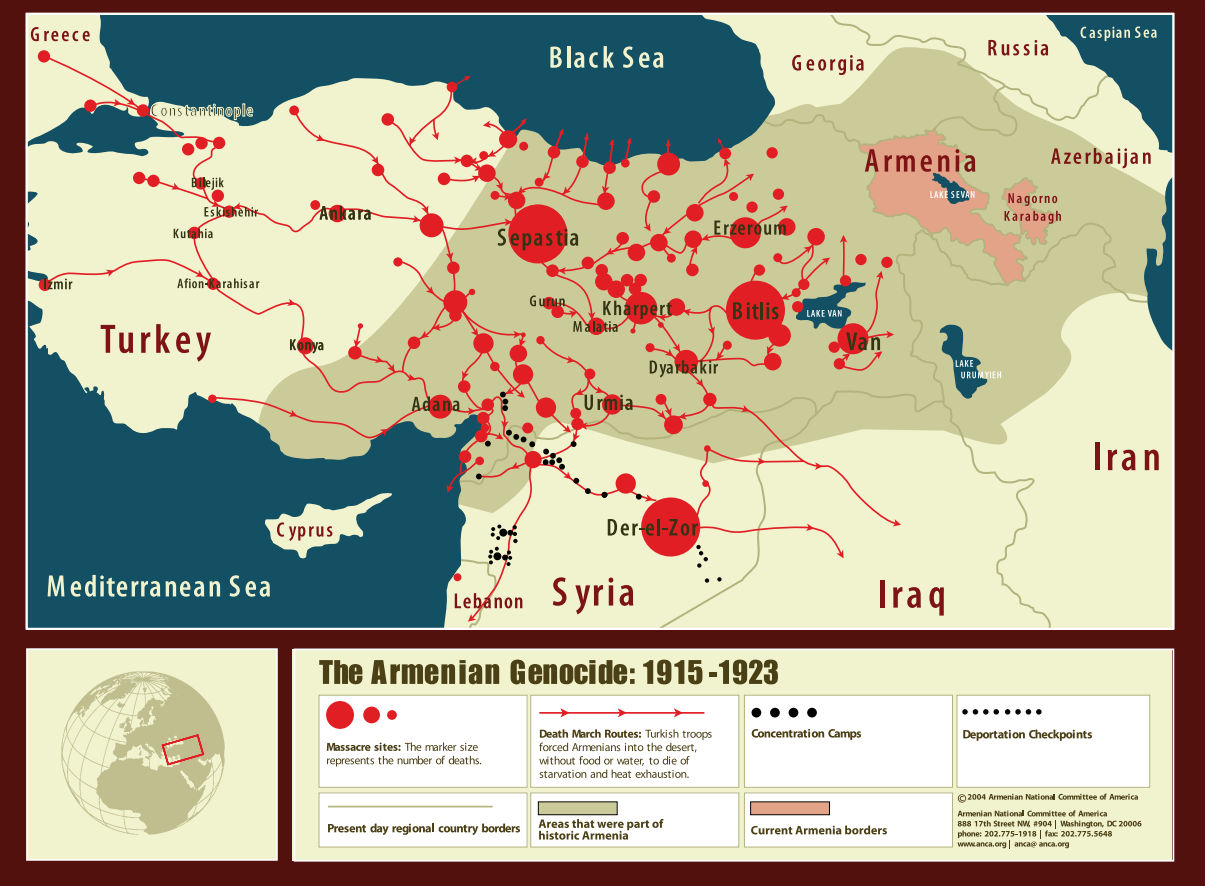

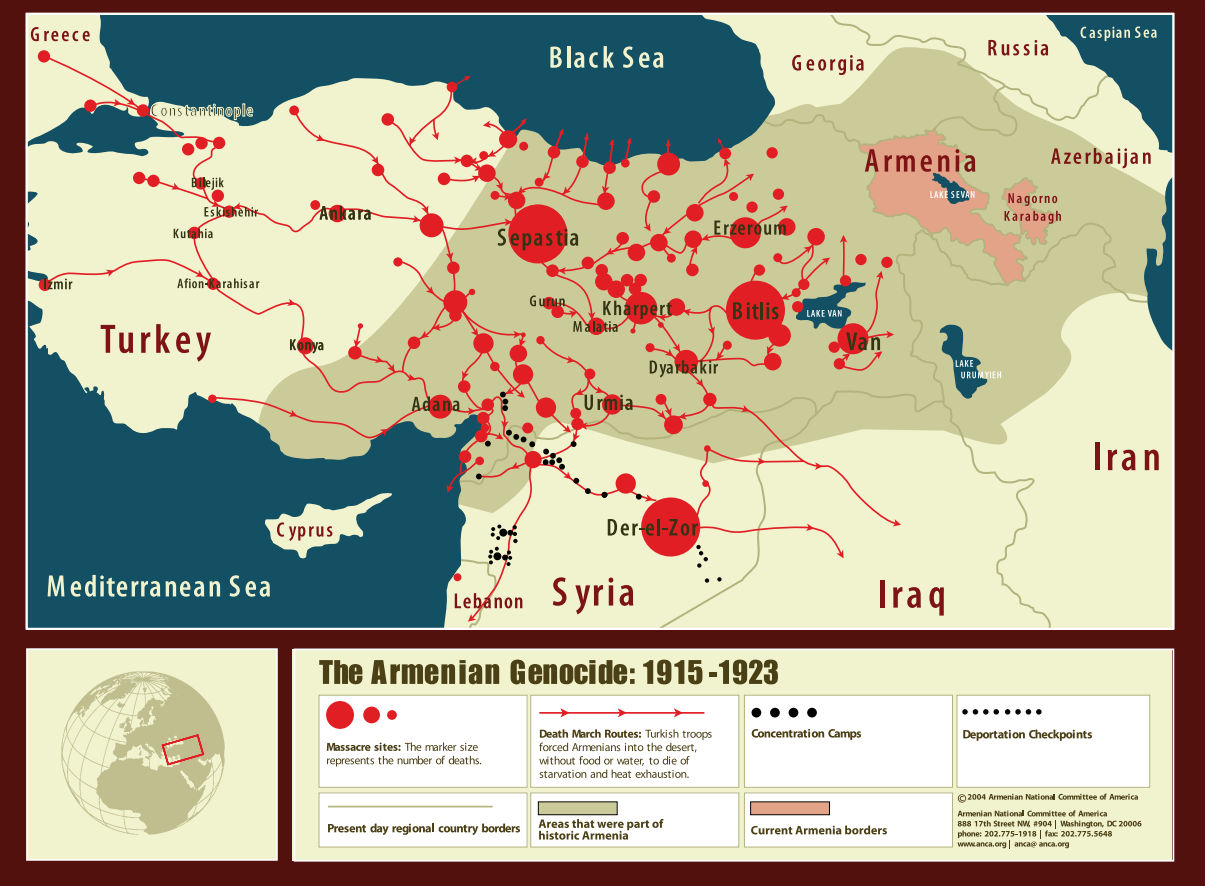

Deportation Routes and Camps

Right Click on Image to See Larger-Sized Map in Separate Window

|

100 Years Ago:

The Polish-Soviet War Heats Up

Soviet Troops Headed for the Polish Front

By Jaroslaw Centek, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Poland

Earlier Hostilities in 1919

The first clash of arms between the Poles and Bolsheviks took place in Vilnius in January 1919, shortly after the Germans had abandoned the city. The Poles had just established their own self-defense troops. Poland had no eastern border and the Bolsheviks wanted to expand their revolution to Western Europe, making war between them inevitable. A short time later the Red Army captured the city.

Poland’s head of state, Jozef Pilsudski (1867-1935), decided to launch an offensive in order to recapture the city. This operation proved to be a success because the Bolsheviks were also heavily engaged in fighting against the counterrevolutionary White Russian troops. Polish troops advanced as far as the Beresina River, while their forces to the left remained at the Dvina River. A White victory in the Russian Civil War would have been counterproductive for Poland, since its territory could then have been limited to the Bug River in favor of White Russia. For that reason, the Poles refrained from any further offensive action, allowing the Bolsheviks to overcome the counterrevolutionary threat of the White Russian troops.

Pilsudski Inspecting His Forces

Polish-Ukrainian Offensive on Kiev

In 1919, hostilities had been quite limited since the Bolsheviks were heavily engaged in the civil war in Russia. As stated before, the Poles were not interested in a White victory. Furthermore, they made the most of the low activity on the front, using the time to organize their forces. It was obvious that a strong campaign a year later would be decisive for the entire war. Both sides–the Bolsheviks and the Poles–thus prepared for a powerful offensive.

Pilsudski succeeded in forming an alliance with Symon Petliura (1879-1926), president of the Ukrainian People’s Republic. Petliura wanted to preserve an independent Ukrainian state, albeit at the cost of Eastern Galicia, which he agreed to cede to Poland. The allies started the campaign by attacking Kiev which was finally freed from Bolshevik control in early May 1920. However, they were unable to install an effective Ukrainian administration in the captured territories before a massive counteroffensive began.

At the end of May 1920, the Soviet 1st Horse Army emerged on the Ukrainian front, forcing the Polish troops to retreat. Soon after, Mikhail Tukhachevsky (1893-1937), commander of the northern front, launched his own offensive in the direction of Vilnius, Minsk, and Warsaw. Both forces were approximately equal–the Poles and the Ukrainians had about 110,000 to 120,000 soldiers while Bolsheviks possessed 120,000 to 140,000.

On 5 July 1920, the Polish front in the north collapsed. The Poles, who sought British mediation, were obliged to accept harsh conditions: namely to agree to the River Bug as their eastern border and to grant Vilnius to Lithuania. However, the Bolsheviks were so convinced of their ultimate victory that they rejected the settlement and continued hostilities. At the beginning of August 1920, they had moved the front to the Bug and captured the fortress of Brest Litovsk.

Stalin and Tukhachevsky Would Both Be Blamed for the Soviet Defeat

Battle of the Vistula

The Polish situation was critical, given the intensified enemy pressure at the Bug River. Thus, it was necessary to retreat to the last possible line of defense–the Vistula River. The Polish high command decided to regroup and form an assault group on the Wieprz River, on the left flank of the Soviet advance. The Poles were determined to defend the right bank of the Vistula in the vicinity of Warsaw, which resulted in heavy fighting. Apart from concentrating their forces in that area, the Soviets also advanced in the northern direction in order to cross the Vistula north of the Polish capital and capture it from the western side, as happened in 1831.

During those dramatic days in mid-August 1920, the Poles succeeded not only in stopping the advance towards Warsaw but also in regrouping their forces in preparation for a massive counteroffensive. On 15 August 1920, the day of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Poles attacked on the left flank; a day later they began an attack on the right wing from the Wieprz line. The enemy was completely surprised and failed to put up any significant resistance.

The "Manoeuver from Wieprz" was an operational masterpiece. It is difficult to determine its authorship, but most probably it was either the Polish chief of the general staff, General Tadeusz Rozwadowski (1866-1928), or the head of state and supreme commander, Josef Pilsudski. The contribution of French general Maxime Weygand (1867-1965), who is sometimes credited with the initiative, is somewhat unlikel since French doctrine favored static warfare. In the course of the Vistula battle, the Soviets' northern front was crushed. The remnants withdrew to the east or crossed the German border in East Prussia and applied for internment. However, the Germans sent them back to Russia.

Battle of the Neman

The last main battle of the war took place at the Neman River between 20 and 26 September 1920. This time the Poles attacked from the outset. Despite some Soviet counterattacks, the Polish troops crushed the enemy's resistance. Tukhachevsky had to retreat, and his front found it impossible to restrain the Polish forces in pursuit. However, the Poles were also exhausted, so both sides decided to sign a truce in October 1920.

Polish Officers with Captured Soviet Flags

Peace Treaty in Riga

The peace negotiations were conducted in the Latvian capital of Riga. Since the Poles had been victorious, they would have been entitled to demand a border well to the east of the River Bug. The members of the Polish delegation, however, were unwilling to incorporate too much territory where Poles would be a minority. Therefore, Minsk was left to the Bolsheviks and the new border was drawn well to the west of the ceasefire line. The new frontier closely resembled the old one of the years 1793-1795, of course with some corrections in favor of Poland

Source: International Encyclopedia of the First World War

|

The United States and the "G" Word

Armenian Genocide Memorial at Fresno, California

Fresno Has a Large Local Population of Armenian Ancestry

The U.S. State Department on Tuesday, 17 December 2019, rebuked the Senate’s latest move to recognize the mass killing and deportation of Armenians by the Ottoman Empire during the first half of the 20th century as genocide, releasing a statement that the administration continues to view the events as “one of the worst mass atrocities.” [Eight former U.S. secretaries of state, both Republican and Democrat, have signed a petition calling for refraining from passing this resolution.]

“The position of the Administration has not changed,” State Department spokeswoman Morgan Ortagus said in a statement. “Our views are reflected in the President’s definitive statement on this issue from last April.”

The global Armenian Remembrance Day is marked on 24 April each year and was commemorated by President Trump with a statement recognizing that beginning in 1915, more than 1.5 million Armenians were “deported, massacred or marched to their deaths” under the rule of the Ottoman Empire.

The president did not describe the events as a genocide.

Turkey has spoken out against the U.S. government’s defining of these events as genocide. It claims that the events of the early 20th century are disputed and lack academic consensus.

Last week, the Senate passed by unanimous vote a resolution recognizing the Armenian genocide as official U.S. policy.

“I’m thankful that this resolution has passed at a time in which there are still survivors of the genocide who will be able to see that the Senate acknowledges what they went through,” Sen. Bob Melendez (D-N.J.) said on the Senate floor.

The House [earlier] passed their own version of the resolution in a vote of 405 to 11.

The passage of the resolution was meant as a rebuke of Turkey in response to Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s October decision to launch an offensive into northeastern Syria against Syrian Kurdish forces that the U.S. is allied within the fight against ISIS. The resolution is nonbinding, expresses the sense of the Senate, and does not need to be signed by the president. The White House had lobbied senators to block the resolution at least three times before it succeeded in coming to the floor.

Source: The Hill, 17 December 2019

|

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications

|

Order Our

WWI Musical CD

Click on Image for Information

|

Shop at

Amazon.com

|

Order the Complete Collection

Over the Top Magazine

Click on Image for Information

|

A World War One Film Classic

Since we are focusing on the Armenian Genocide in this issue of the Trip-Wire, I wanted to include the best film I know on the subject in this column. The Promise was directed by Terry George, who was also responsible for the award-winning Hotel Rwanda. Why this movie flopped at the box office is a mystery to me, but I just re-watched it and stand by this recommendation. The film tells the story of the opening stages of the catastrophe, through the outbreak of war and the July 1915 deportation proclamation, up through the remarkable rescue of 4,000 fleeing ethnic Armenians from the mountain Musa Dagh near the Syrian/Turkish border by the French Navy in September 1915. The main narrative ends at that point, so extreme, brutal depictions of starving caravans of women and children (and absent men) are shown only in a brief epilogue to the main film.

From what I could learn on the Internet, critics were split about 50-50 on recommending The Promise. Apparently, some were very put off by the love story (two guys in love with the same woman) at the center of the action. Others seem to think the film was too beautifully photographed and this somehow overly romanticized the genocide. To me, criticizing a Hollywood production for having a love story and great photography is a bit absurd. The Promise accomplishes all one can hope for from a movie–providing some interesting insights into an important historical event that encourages viewers to want to learn more about what really happened. The CD is available for purchase or streaming from Amazon and for viewing from Netflix.

|

|

Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

(Or send it to a friend)

(Or send it to a friend)

|

Design by Shannon Niel

Content © Michael E. Hanlon

|