February |

Access |

Smaller Successes of the AEF Doughboys on the Move

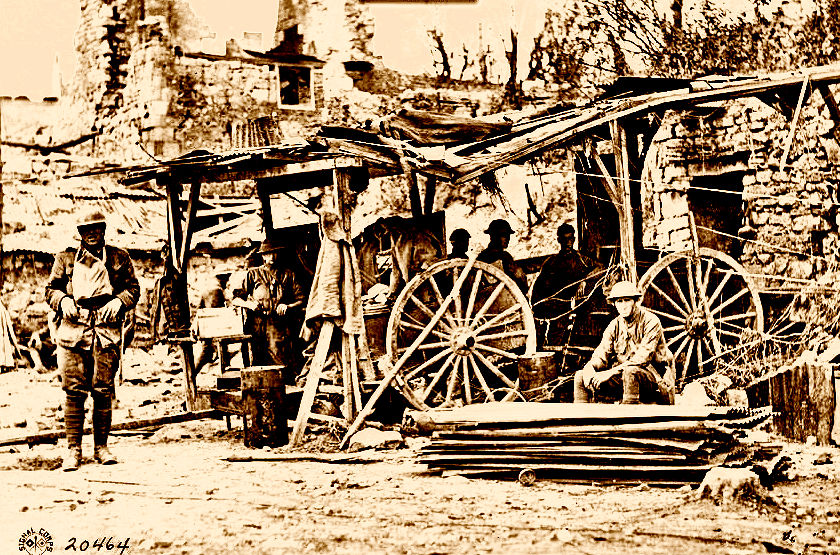

The "Red Arrow Boys" Take Juvigny: 28 August — 2 September 1918 Establishing Comm Lines to the Juvigny Plateau

French Tanks and American Infantry

The division was accompanied by war correspondent Don Martin, who quickly filed this account of the final capture of Juvigny that was published the next day in the Paris Herald.

The Red Arrow Occupying Juvigny

The village was taken in an operation which came partly as a surprise to the Boche. One battalion was assigned to charge a German machine-gun position near the railway tracks to the northeast of the village, and another battalion was told to go more to the east and to take the village from the rear. Both battalions performed their tasks on time. The first attack was made at half-past three o’clock on Friday afternoon and the second at seven o’clock. The evening attack resulted in the capture of the village. Now the American line is well outside the village where the soldiers have dug in to await instructions.

Visit Our Daily Blog Click on Image to Visit |

Different Perspectives

Here are the best sources on the AEF available online.

Time Will Not Dim the Glory of Their Deeds. General John J. Pershing

The Doughboys and Trench Warfare An American Trench in the Vosges Mountains

Trench warfare, or at least vivid memories of unpleasant extended periods of service in the trenches, was not a big part of the American experience in the war. One reason for this is that trench warfare effectively ended in the most active parts of the front, when the German Army launched its first of five spring offensives on 21 March 1918. From this point on, American forces in these hot zones were either plugging a gap, as they did at Château-Thierry, or launching an attack.

Soissons

When the sun rose they were still working their way

through the trees. Unexpectedly the guns in the rear of the moving lines

stopped. The battle of Soissons had begun. [18 July 1918]

|

|||||||

The 5th Division's "Red Devils" Take Frapelle,

| ||||||||

|

On 15 July, the Division moved to the Saint-Die sector. The division's four infantry regiments divided the front approximately equally. The 60th Infantry Regiment took the sector between Celles-sur-Plaine and Moyenmoutier; the 61st Infantry Regiment occupied both sides of the Rabodeau; the 11th Infantry Regiment occupied the Ban-de-Sapt sub-sector, and the 6th Infantry Regiment was on the front line in Bois d'Ormont. The 5th Division started patrolling and raiding the German lines regularly, both by night and by day. The first units of the Artillery Brigade joined the division on July 28. The division was then ready for a major offensive action. Their mission was to capture Frapelle and the hill just to its north to dominate and close off the valley below.

On 17 August after an artillery preparation of ten minutes, the attack was launched at 0400 hrs. The 6th Infantry advanced from the west face of the salient behind a rolling barrage. The German defenders, however, were quick to mount a counter-barrage. At 0406 they opened fire and hit the U.S. departure trench, striking some of the other assault waves. Despite the casualties inflicted on the attackers, the defenders withdrew from all be a few strong points. Most objectives were reached promptly.

By 0630 hrs the village of Frapelle was liberated after four years of German occupation. The Germans immediately started a massive bombardment of the Americans, which lasted for three days and nights and included intensive use of mustard gas. The men of the Red Diamond Division organized their positions, built new trenches, and set new wires. A German counterattack failed on 18 August and, by 20 August, the American positions were completely consolidated. The high ground north of Frapelle was held and the valley below barricaded. The sharp salient had been eliminated.

The division left the sector by 23 August and moved to Arches where the headquarters were established. The division lost 729 men in the Vosges. Shortly after that rest, the 5th Division was transferred towards Saint-Mihiel where it participated in the successful St. Mihiel Offensive. The subsequent record of the division was one of the best in the AEF. Somewhere along the line its members had earned the nickname "Red Devils."

Ruined Uniforms of the Division's Mustard Gas Victims

II Corps' Remarkable 14-Mile Advance

to the River Selle

A Selection from Borrowed Soldiers

Prisoners Captured by the 30th Division, 8 October 1918

A number of American divisions

trained under the British in 1918 and became involved in the stopgap efforts during midyear to halt the German onslaught.

Pershing later pulled back most combat elements, but General Haig convinced him of the necessity of leaving some U.S. units with the British. Two National Guard Divisions, the 27th (New York) and 30th (Tennessee and the Carolinas) without their artillery brigades, the 301st tank battalion

(American-operated Mark V British Tanks), and a number of support units would constitute II Corps. These were combined into the U.S. II Corps on the table of organization. Initially deployed

to strengthen defenses in Flanders, it was sent to the British Fourth Army in the Somme sector in September to support offensive operations there. At the end of the month the Corps assisted in the spectacular capture of the St. Quentin

Canal that allowed the breaching of the formidable Hindenburg Line. That operation seems to garner much attention in

histories of the AEF. The subsequent actions of II Corps, however, are just as impressive but seem to be neglected in many

histories. For this issue of the Trip-Wire, AEF historian Mitchell Yockelson describes the early stages and central role of the U.S. II Corps of the British Fourth Army's 14-mile advance during two weeks of October 1918. (See map below.) The selection is from his 2008 work Borrowed Soldiers: Americans Under British Command, 1918.

After breaching the Hindenburg Line on 29 September,

the Fourth Army continued to push forward. The

Beaurevoir Line had not been taken, and Rawlinson

was adamant that his army must complete the

destruction of the final prepared German defenses just

to his east. Once this was accomplished, he would

push the Germans back across open country. {After Australian units captured most of the fortified village of Monbrehain] Rawlinson ordered Monash's troops withdrawn from

the line, and half of the American II Corps undertook

relief of the Australian Corps during the night of 5-6

October. Only the 30th Division was ordered to the

front initially, while both brigades of the 27th Division were in

corps reserve.

Sector Map (Note Scale & Dates of Advance)

With the German Army now forced into open country,

the Fourth Army continued the pursuit, and the

Americans would spearhead most of the attacks.

Because the 117th occupied a sector too far behind

the 118th, it had to straighten its line before the next

attack. A minor action was planned for 7 October to

make this correction. At 5:15 a.m. a rolling

barrage commenced the attack, but the artillery

covered only a portion of the front. As a result, the

British 25th and 50th Divisions, protecting the

American flanks, could not advance. Four hours after the jump-off, 30th Division Commander Major General Lewis

halted the attack when the center companies of the

3rd Battalion established liaison with the 118th and

stopped near Mannions. Although the battalion had

advanced only 500 yards and took heavy casualties, it

captured 150 prisoners of the 20th German Division.

Lewis blamed the losses on failure of the barrage and a

lack of preparation time. His division had been in line

less than a day, and it appeared that not all officers

knew the battle plan.

On the afternoon of 7 October, the Fourth Army issued

an order for the 30th Division to attack again the next

day. The 118th would lead the assault, with one

battalion of the 117th in support. It first required an

advance of 3000 yards on a line running northwest

from Brancoucourt. After securing this line, the

barrage would halt for 30 minutes, and then the

support battalion would pass through and exploit the

second objective, requiring a push of 3000 yards to the

northeast toward the village of Premont. In the hours preceding the jump-off, the Fourth Army

artillery pounded the Germans with 350,000 shells. On

8 October at 5:10 a.m. the infantry moved forward

under a barrage, as well as support from a battalion of

heavy tanks and two companies of Whippets.

Machine-gun fire from the numerous emplacements

around the west of Brancourt-le-Grand raked the lead

elements, preventing progress. Troops from the 6th

Division were held up and could not protect the

American flanks. Fortunately, two hours later

resistance lightened when the Germans retreated,

fighting a rear-guard action. On the right flank,

Company C of the 120th Infantry was pulled from

reserve and was able to advance enough to fill a gap

that developed between the 118th Infantry and the

6th Division. By 7:50 a.m. the 2nd Battalion of the

118th reached its first objective at Brancourt, and by

1:30 p.m. the regiment's 1st Battalion entered the

village. There the elements of the 118th mopped up

and then consolidated a line and dug in for the night.

On this day, the action of three men of the 30th

Division earned the Medal of Honor. In one instance,

Sgt. Gary Evans Foster accompanied an officer to

attack a machine-gun nest in a sunken road near

Montbrehain. When the officer was wounded, Foster

single-handedly killed several of the Germans with

hand grenades and his pistol and then brought 18 back

as prisoners.

That evening, II Corps Commander Read again notified the 30th Division

there was no time to rest, but to resume attacking at

5:20 a.m. the next morning in the direction of St.

Souplet. The eventual object was to secure the Selle River and

the high ground from St. Benin to Molain. Such an

attack, the American officers were told, would not be

easy as it necessitated advancing a great distance

through several villages, farms, and woods that

probably contained enemy units. Yet, day to day, the Doughboys would continue their advance averaging a mile per day for the next eleven days. The 30th division would be joined by the 27th division for a period and then sent to rest while the New Yorkers carried on beyond the River Selle until it too was exhausted. By the time orders for their relief had come the two divisions had lost 6,100 men, killed and wounded.

27th Division Reinforcements Crossing the Selle, 19 October 1918

The 1st British

Division took over the 30th Division sector and the 6th

British Division relieved the 27th by 20 October. Although it was not

known at the time, the war was over for II Corps. Its

27th Division moved to Corbie, and the 30th went to

Querrieu for training. . . considering how the two

divisions of the corps were essentially new to combat,

compared with their British and Australian

counterparts, they had done extraordinarily well. The

American infantry and machine-gun units had received

good instruction from the British and Dominion forces

and were able to apply what they had learned in this

final operation. This was done against a German

opponent that was far from collapsing. A historian of

the operation writes, the Germans “fought hard and

skillfully used defense-in-depth doctrine. Their position

and intervention units were well organized, and the

position divisions were relatively strong in manpower.”

100 Years Ago:

|

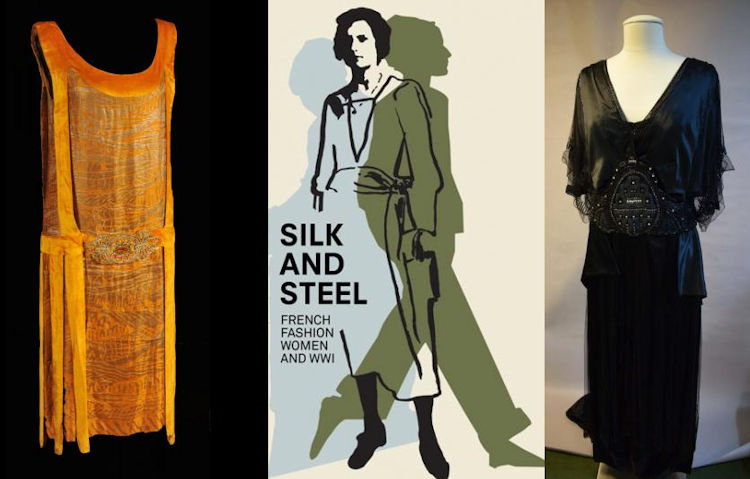

French Wartime Fashion Remembered At the National WWI Museum

I want to commend the staff of the National World War I Museum for their imaginative efforts to keep the public interested in the historical importance of the war by presenting imaginative and fresh programs that look at its surprising aspects. I've been meaning to write this article for some time, but the museum's latest special exhibition, Silk and Steel: French Fashion, Women and WWI, which is showing through 11 April, is a perfect example of what I like to see. Obviously intended to attract an audience other than hard core military history types, Silk and Steel will allow visitors, who may otherwise have never traveled to the museum to learn how deeply connected the war is to our 21st-century culture.

Silk and Steel features original dresses, coats, capes, hats, shoes, and accessories. Topics presented are the evolution of the war-time silhouette, Parisian designers during the war, military uniforms’ influence, women’s uniforms in France and America, war work, economics of fashion, and post-war emancipation.

Original clothing and accessories are on loan from many other museums.

French Fashion, Women, and the First World War was organized by Bard Graduate Center Gallery, New York. An initial iteration of this exhibition called Mode & Femmes 14–18 was presented at the Bibliothèque Forney in Paris by Bibliocité.

A World War One Documentary

Elsie Janis, Sweetheart of the AEF, Singing for the Troops

This 23-minute gem from the 1960s CBS World War I series features the memorable music of the Great War. As do all the episodes of that excellent series, it also includes the authoritative and appropriate-sounding for the period Robert Ryan as narrator and some of the series' best-restored film footage. Over the years, I've found this brief documentary an evocative preliminary warm-up for any presentation on the First World War. It's a portal to a more sentimental and simpler time. This version of the video eliminated the opening reference to CBS and replaced a small amount of the initial footage. The remaining part, however, seems to me to be all from the original version.

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon