March |

Access |

Emperor Franz Josef and Archduke Franz Ferdinand

|

||||||||

Mary Borden |

The pale yellow glistening mud that covers the naked hills like satin,

The grey gleaming silvery mud that is spread like enamel over the valleys,

The frothing, squirting, spurting liquid mud that gurgles along the road-beds,

The thick elastic mud that is kneaded and pounded and squeezed under the hoofs of horses.

The invincible, inexhaustible mud of the War Zone. . .

This is the hymn of mud-the obscene, the filthy, the putrid,

The vast liquid grave of our armies. It has drowned our men.

Its monstrous distended belly reeks with the undigested dead.

Our men have gone into it, sinking slowly, and struggling and slowly disappearing.

Our fine men, our brave, strong, young men;

Our glowing red, shouting, brawny men.

Slowly, inch by inch, they have gone down into it,

Into its darkness, its thickness, its silence.

America Demobilizes Her Wartime Forces

26th Yankee Division Arrives in Boston Aboard USS Agamemnon,

7 April 1919

The U.S. Army was utterly unprepared to demobilize its unprecedentedly huge army when the Armistice occurred. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, later wrote: "The collapse of the Central Powers came more quickly than even the best informed military experts believed possible." In fact, planning for eventual demobilization had begun only a month before hostilities ceased. The wartime American military had grown to 4.7 million with the largest part serving in the army, including 2 million men in France on 11 November 1918. The easiest group to deal with were the men in training camps stateside who had recently entered the service. Between the Armistice and New Year's Day, 690,000 men were mustered out of the Army. However, the much bigger issue was what to do about the men overseas and the forces ready to ship out had the fighting continued into 1919.

Taking the welfare of the nation as well as that of the Army into account, the demobilization planners considered four distinctly different ways of demobilizing the emergency troops: soldiers could be separated by length of service; by industrial needs or occupation; by locality (through the use of local draft boards); or by military units. For the Great War, length of service didn't make any sense. The first three possibilities offered insurmountable difficulties. Most of the combat forces had been overseas for less than a year. Compiling records for every soldier's occupational history and need for those skills in the peacetime economy would take an unacceptably long time. Finally, placing the load of mustering out military men on local draft boards was simply unworkable. The boards had no facilities for processing troops and they were semi-independent local entities making an effort to make the process uniform across the country futile. The Secretary of War described the implementation of the fourth option:

. . . the policy adopted was to demobilize by complete organizations as their services could be spared, thus ensuring the maximum efficiency of those organizations remaining, instead of demobilizing by special classes with the resulting discontent among those not given preferential treatment and retained in the service, thus lowering their morale and efficiency and disrupting all organizations with the attendant general discontent.

27th New York National Guard Division Marches Down Fifth Avaenue, 24 March 1919

Discharge of troops was largely accomplished at demobilization centers throughout the country, where camp personnel conducted physical examinations, made up the necessary papers to close all records, checked up property, adjusted financial and other accounts, and generally gathered up the loose ends. Many organizations remaining in the zone of interior were not immediately inactivated. Men were needed to man the ports of debarkation, the convalescent and demobilization centers, the supply depots, the base and general hospitals, and the garrisons along the Mexican border and bases outside of the United States. Accordingly, many men assigned to these duties were retained in service for many months.

Most important, the processes of demobilization were to be as rapid as conditions would permit. Three groups–coal miners, railroad employees, and railway mail clerks–were discharged immediately; and instructions were issued specifying the order in which various organizations should be demobilized, beginning with the replacement battalions in the zone of the interior and ending with the combat divisions. It was General Pershing's job to say who should return from Europe and when.

When a soldier was discharged he received all pay and allowances due him, plus a bonus of $60. Each enlisted man was also given a uniform, shoes, and overcoat, if the weather was cold, otherwise a raincoat. It is interesting to note that men returning from overseas were allowed to retain their gas masks and helmets as souvenirs. When a soldier had been paid his allowance he was marched directly to a place where he could purchase a railroad ticket to his home.

363rd Infantry Regiment at San Francisco's Palace of Fine Arts Just Before Mustering Out, 22 April 1919

The process proved chaotic–the term "madhouse" was occasionally invoked–and was subject to countless complaints, many well deserved. America's World War One demobilization, however, did work quickly. Within one year of the Armistice, the Army had sent 3.4 million officers and men back to civilian life.

Sources: History of Personnel Demobilization in the United States Army, U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps; Panoramic Photos from the Libary of Congress, New York from the National Archives

Austria-Hungary in the

First World War

Austria-Hungary was a declining imperial power when it helped instigate the war in 1914. Its hopes for revitalization were soon shattered by the compounding catastrophes of stupendous battlefield casualties and shortages at home. In the end, it was one of four empires deposited on the scrap heap of history as a result of the war. The details of Austria-Hungary's demise, however, makes for fascinating reading.

![]() Austria-Hungary WWI Fact Sheet

Austria-Hungary WWI Fact Sheet

![]() Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I (Multiple Articles, PDF)

Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I (Multiple Articles, PDF)

![]() War Aims of Austria-Hungary

War Aims of Austria-Hungary

![]() Hungarian War Aims During WWI (PDF)

Hungarian War Aims During WWI (PDF)

![]() Wikipedia Index on Austria-Hungary WWI Battles

Wikipedia Index on Austria-Hungary WWI Battles

![]() The War Economy of Austria-Hungary

The War Economy of Austria-Hungary

![]() Last Offensive of Austria-Hungary on the Piave

Last Offensive of Austria-Hungary on the Piave

![]() The First World War and the End of the Habsburg Empire (PDF)

The First World War and the End of the Habsburg Empire (PDF)

![]() Treaty of Saint-Germain (Austria)

Treaty of Saint-Germain (Austria)

![]() Treaty of Trianon (Hungary)

Treaty of Trianon (Hungary)

The Dual Monarchy's Approach to Mobilization

Historian Alexander Watson argues that the governments of Germany and Austria-Hungary started the

war with different levels of preparedness and approaches to public support for the

war. The two states’ techniques for mobilizing their armies and civilian populations

in 1914 had consequences for not only their conduct of the war but also the outcome

of the revolutions that followed from their defeat in 1918. The German government

relied on popular enthusiasm as symbolized by the Burgfrieden, a political

compromise between all the political parties in the Reichstag, including the Social

Democrats.

The leaders of the Dual Monarchy, in contrast, were suspicious of

popular mobilization. Their prewar plans eschewed civilian participation in favor of

military control. Franz Joseph refused to recall the Austrian Reichsrat to cast a vote

in support of the war. Instead, the Austrian Parliament building was turned into a

military hospital. The Habsburg leaders came to embrace civilian mobilization along

national and ethnic lines. This decision haunted them in the last years of the war. By

1918, the nationalities' support for the dynasty had flagged because of chronic food

shortages and the political stalemate over constitutional reforms in both halves of

the Dual Monarchy.

(From Matthew Lungerhausen's review of Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in WWI on H-Net)

Portent

If it is said that the war is won, it would perhaps be more accurate to say that there is a lull in the storm. At the very least, it is necessary to provide for all eventualities. Recent discoveries have enabled us to pierce the enemy's designs to a greater extent than hitherto. They were not merely a dream of military domination on the part of Prussia, but a definite conspiracy expressly aiming at the extermination of France. Industrially France is extremely difficult to reconstruct, whereas Germany has kept her factories intact and ready to start working efficiently forthwith. Indeed, industrially and commercially, as between France and Prussia, the victory is the latter's. . . the war debt of Germany is almost entirely domestic and can easily be repudiated, while that of France must be paid. In the immediate future we shall have to pay regularly abroad immense sums, by way of interest solely, out of our internal resources.

Georges Clemenceau,

Interview, 9 February 1919

Despite my retirement from the business, there will still be possibilities for you to visit the battlefields of the Great War.

AEF Battlefields

2019

From: Valor Tours, Ltd. / Mike Grams, Tour Leader

When: September 2019

Details: Request brochure via Email

HERE.

27 April 2019, 10am: League of World War I Aviation Historians Meeting at the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. Details

HERE.

To commemorate the Centennial of the signing of the Treaty of Versailles and to celebrate American philanthropy before and after World War I a Versailles Palace Dinner will be held in the palace's magnificent Hall of Battles on 28 June 2019. Proceeds from the event will be dedicated to building America's National WWI Memorial at Pershing Square. For information email

HERE

Visit Our Daily Blog

Looking Back: A Retrospective of the War

Part III

This is our third historic banner provided by the San Francisco War Memorial's World War I Armistice Centennial Commemorative Committee. Visit HERE to learn more about the commemorative exhibition being held in the City by the Bay.

A German Admiral Evaluates the

Prospect of America Joining the War

Announcing unlimited submarine warfare will once again force the government of the United States to answer the question of whether or not it wants to experience the consequences of the position it has taken on submarine warfare up until now. I am very much of the opinion that war with America is such a serious matter that everything must be done to avoid it. In my opinion, however, the aversion to this break must not lead us to shrink from using, in the decisive moment, the weapon that promises us victory.

Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff

Author of the Memorandum

In any case, one should plan for the worst and make clear to ourselves what influence America joining our enemies would have on the course of the war. In regard to shipping capacity, this influence can only be very small. It is not to be expected that more than a small percentage of the tonnage of Germany and its Allies in American or other neutral harbors could be quickly put into service for the trip to England. By far the largest part could be damaged in such a way that it would not be able to travel in the first months. The preparations for this have been taken. There would also be no crews for these ships at first. Just as little decisive impact can be attached to American troops–who, on account of limited freight capacity, cannot be brought over in considerable numbers–and American money, which cannot make up for insufficient technical supplies and tonnage.

The only remaining question is how America would respond to a peace such as England would be required to make. It is unlikely that America will then decide to continue to fight us alone, as America will have no means with which to harm us significantly, whereas its ocean traffic will be damaged by our submarines. On the contrary, it is to be expected that America will become a member of a peace treaty with England, in order to arrive at a healthy economic situation once again.

I, therefore, conclude that an unrestricted submarine warfare initiated soon enough to bring about peace before the world harvest in summer 1917– that is, before August 1– must hazard the consequences of a break with America, for no other choice remains to us. Despite the danger of a break with America, unlimited submarine warfare, begun soon, is the right means for ending the war successfully. It is also the only means to reach this goal.

A U-boat Is Resupplied with Torpedoes at Sea

Since the fall of 1916, when I declared that the moment had arrived to strike against England, our situation has fundamentally improved. The shortage in the world’s harvest, combined with the effect of the war on England, has once again given us the opportunity to bring about a decision in our favor before the next harvest. If we do not use this opportunity, which according to my calculations will be our last, then I do not see any possibility other than that of mutual exhaustion.

In order to achieve the necessary effect in time, it is necessary for unlimited submarine warfare to begin on February 1st at the latest. From Your Excellency I request a statement explaining whether the military situation on the continent, especially vis-à-vis those nations which are still neutral, will allow this. I need three weeks for the necessary preparations.

Source: Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff to Field Marshall von Hindenburg (22 December 1916)

Harry Moseley: Greatest Scientific Loss of the First World War

The Farm Sector Where Moseley Fell

|

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications |

||

Order Our

|

Shop at |

Order the Complete Collection

|

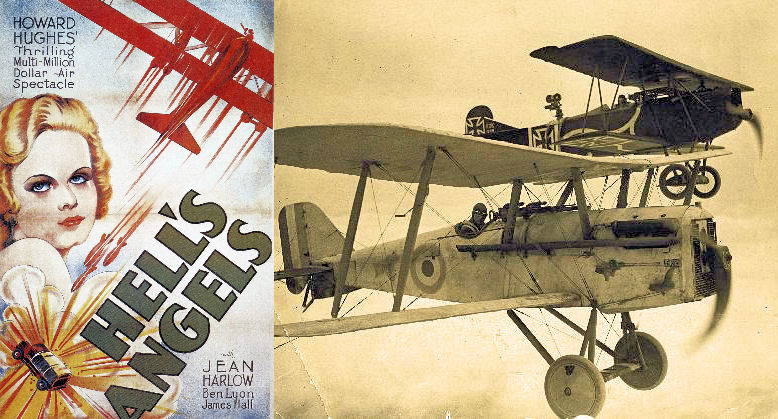

A World War One Film Classic

Howard Hughes produced and directed Hell's Angels, the most expensive film ever made by 1930. Set during World War I, Hell's Angels is the story of three Oxford buddies: two brothers (Ben Lyon and James Hall) and one German (John Darrow) with a shared love interest (Jean Harlow in her film debut). Its fabulous collection of aircraft and depictions of combat–including a Zeppelin raid–makes it a must-see for all WWI enthusiasts. [P.S. The Editor's dad and uncle were extras in the sequences flown over San Francisco Bay.]

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon