March |

Access |

Reflecting on the Gas War

British Victims of Phosgene Gas at Fromelles, July 1916

|

||||||||

|

Gas Warfare in the Great War

Australian Mustard Gas Victims

By James Patton

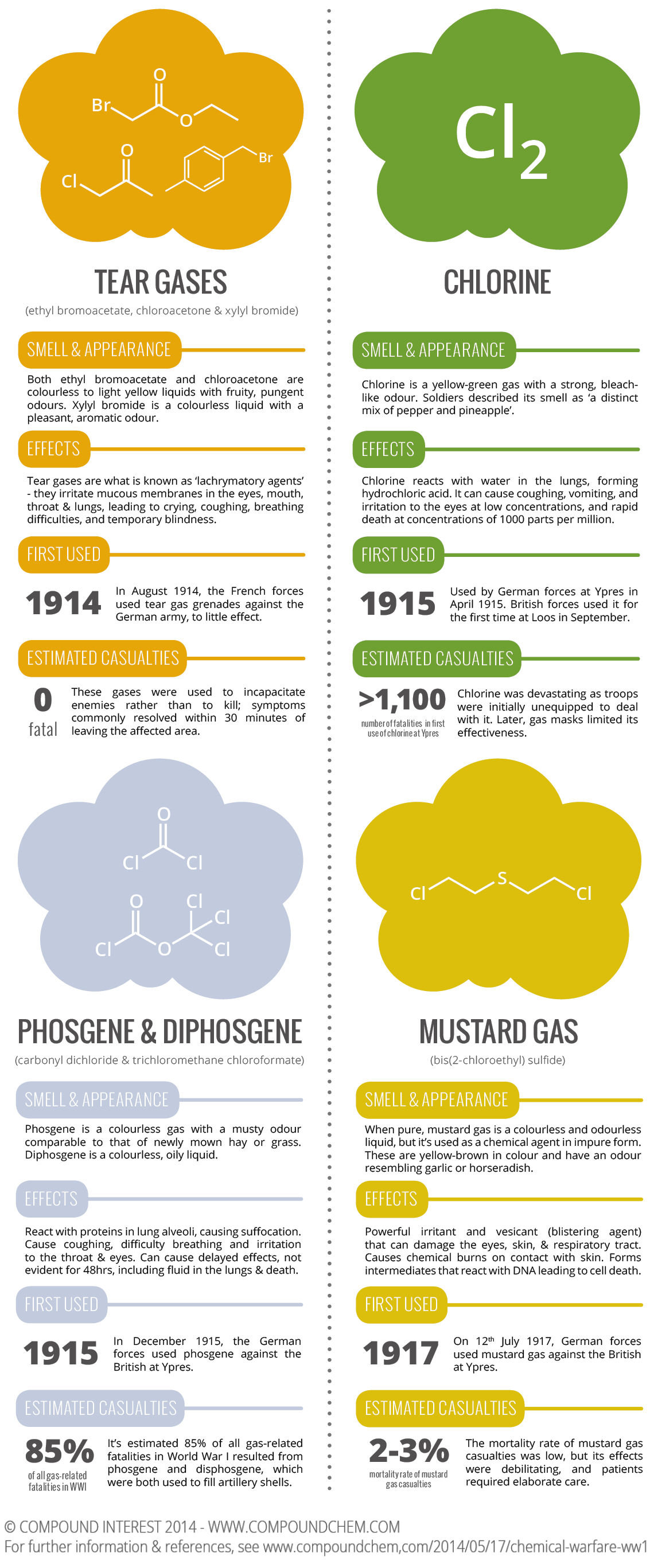

One of the enduring hallmarks of WWI was the large-scale use of chemicals weapons, commonly called simply "gas." Although chemical warfare caused less than 1% of the total deaths, the psywar or fear factor was formidable, and chemical warfare was prohibited by the Geneva Protocol of 1925. It has been occasionally used since then but never in WW1 quantities, and production of some of the chemicals continues as they have peaceful uses–for example, phosgene is an industrial reagent, a precursor of pharmaceuticals and other important organic compounds.

Several chemicals were weaponized in WWI. France was actually the first to use gas–they deployed tear gas in August 1914. The agent used was either xylyl bromide, which is described as smelling 'pleasant and aromatic' or ethyl bromo acetate, described as "fruity and pungent"; both are colorless liquids and have to be atomized. As lachrymatory agents, they irritate the eyes and cause uncontrolled crying. Large doses can cause temporary blindness. If inhaled they also make breathing difficult. Symptoms usually resolve by 30 minutes after contact. Tear gas was never effective.

The German gas warfare program was headed by future Nobel Prize winner Fritz Haber, who also developed the process by which nitrates could be made from atmospheric nitrogen. Haber's first try was chlorine, which he debuted at Ypres in April 1915. Chlorine is a diatomic gas, about two and a half times denser than air, pale green in color and an odor which was described as a 'mix of pineapple and pepper'. It can react with water in the lungs to form hydrochloric acid, which can quickly lead to death. At lower concentrations, it can cause coughing, vomiting, and eye irritation.

Chlorine was deadly against unprotected soldiers. It's estimated over 1,100 were killed in the first use at Ypres. But the Germans weren't prepared for how effective it would be and were unable to exploit the advantage, and gained little ground.

Kaiser Wilhelm II Inspecting Gas Launching Tubes

Chlorine's usefulness was short-lived. Its color and odor made it easy to spot, and since chlorine is water-soluble even soldiers without gas masks could minimize its effect by placing water-soaked rags over their mouth and nose. Additionally, releasing the gas in a cloud posed problems, as the British learnt to their detriment when they attempted to use chlorine at Loos. The wind shifted, carrying the gas back onto their own men.

Phosgene (carbonyl dichloride) was Haber's next choice, probably used first at Ypres by the Germans in December 1915. Phosgene is a colorless gas, with an odor likened to that of "musty hay," but for the odor to be detectable, the concentration had to be at 0.4 parts per million, or several times the level at which harmful effects occur. Phosgene is highly toxic, due to its ability to react with proteins in the alveoli of the lungs and disrupt the blood-air barrier, leading to suffocation.

Phosgene was much more effective and deadly than chlorine, though one drawback was that the symptoms could sometimes take up to 48 hours to manifest. The immediate effects are lachrymatory. Subsequently, it can cause the build-up of fluid in the lungs, leading to death. It's estimated that as many as 85% of the 91,000 gas deaths in WWI were a result of phosgene or the similar agent called diphosgene (trichloromethane chloroformate).

Every Soldier in This Italian Command Bunker North of Caporetto Died in the Initial Gas Barrage of 24 October 1917 – Most Before They Could Reach for Their Gas Mask

The most commonly used gas was "mustard gas" [bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide]. In pure liquid form this is colorless, but in WWI impure forms were used, which had a mustard color with an odor reminiscent of garlic or horseradish. An irritant and a strong vesicant (blister-forming agent), it causes chemical burns on contact, with blisters oozing yellow fluid. Initial exposure is symptomless, and by the time skin irritation begins, it is too late to take preventative measures. The mortality rate from mustard gas was only 2-3% of casualties, but those who suffered chemical burns and respiratory problems had a long hospitalization and if they recovered were at higher risk of developing cancers during later life.

Chloropicrin, diphenylchlorarsine, American developed Adamsite (diphenylaminechlorarsine) and others were irritants that could bypass gas masks and make soldiers remove their masks, exposing them to phosgene or chlorine.

Gases were often used in combinations. Most gas was delivered by artillery. The agent(s) were in liquid form in glass bottles inside the warhead, which would break on contact and the liquid would evaporate. Shells were color-coded in a system started by the Germans. Green Cross shells had the pulmonary agents: chlorine, phosgene, and diphosgene. White Cross had the tear gases. Blue Cross had the "mask breakers" like chloropicrin. Gold (or Yellow) Cross had mustard gas. (Don't miss our graphic summary of the four types of gas on the next page below.)

Sources: This article, in slightly different form, first appeared on the website of the University of Kansas Medical Center Website

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

Different Perspectives

There were many different approaches to chemical warfare during the war and it required a national level of support from science, industry, and the military in each nation to make it happen on the battlefields. Also, chemical and now biological warfare are still part of life in the 21st century.

![]() Science, Industry, and Gas Warfare in WWI

Science, Industry, and Gas Warfare in WWI

![]() Early Uses of Gas in the Great War

Early Uses of Gas in the Great War

![]() Eyewitness to the First Major Gas Attack on the Western Front

Eyewitness to the First Major Gas Attack on the Western Front

![]() Caporetto: The War's Most Effective Gas Assault

Caporetto: The War's Most Effective Gas Assault

![]() Review of World War I Gas Warfare Tactics and Equipment

Review of World War I Gas Warfare Tactics and Equipment

![]() American Medical Response to Gas Warfare

American Medical Response to Gas Warfare

![]() Why Not WWII?

Why Not WWII?

![]() Truths and Myths of Chemical Warfare Today

Truths and Myths of Chemical Warfare Today

![]() Iran's Victims of Nerve Agent Warfare

Iran's Victims of Nerve Agent Warfare

![]() Lessons from WW1 for Modern Medical Care of Chemical Warfare Victims

Lessons from WW1 for Modern Medical Care of Chemical Warfare Victims

News Report of Gas Attack at Langemarck

[The] vapor settled to the ground like a swamp mist and drifted toward the French trenches on a brisk wind. Its effect on the French was a violent nausea and faintness, followed by an utter collapse. It is believed that the Germans, who charged in behind the vapor, met no resistance at all, the French at their front being virtually paralyzed.

New York Tribune 27 April 1915

The Worst

Detail, Sargent's "Gassed"

Aftermath of a Mustard Gas Attack

Despite the fact it was infrequently fatal for the victim, Mustard gas (Dichlorethyl sulphide) was the most dreaded chemical weapon of the Great War. Unlike the other gases, which attack the respiratory system, this gas acts on any exposed, moist skin. This includes, but is not limited to, the eyes, lungs, armpits, and groin. A gas mask could offer very little protection. The oily agent would produce large burn-like blisters wherever it came in contact with skin. It also had a nasty way of hanging about in low areas for hours, even days, after being dispersed. A soldier jumping into a shell crater to seek cover could find himself blinded, with skin blistering and lungs bleeding.

Source: Understanding Inter-

national Counter Terrorism

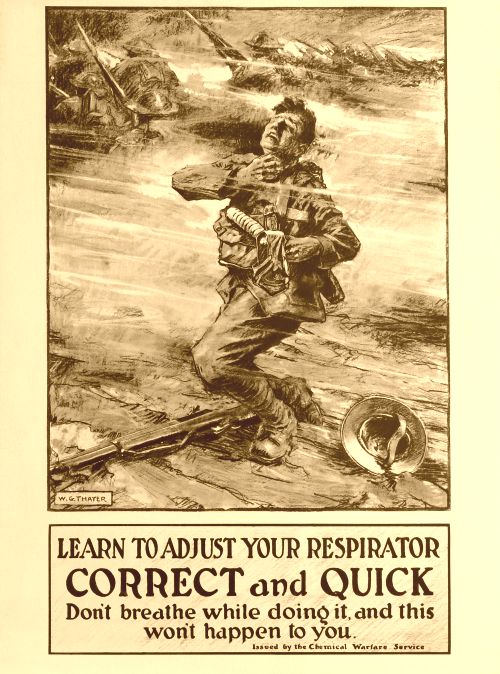

Gas! GAS! Quick Boys!

The most vivid and famous literary description of a gas attack is contained in Wilfred Owen's poem, "Dulce et Decorum Est." Interestingly, Owen's unit never experienced a gas attack while he was deployed in the front lines with it.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime. –

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues. . .

Doughboys in the Meuse-Argonne

Detail, Lost Battalion Memorial

Charlevaux Mill, France

From: Lost Battalion Tours / Rob Laplander & Mike Cunha, Tour Leaders

When: 8-15 August 2020

Details: Download Flyer

HERE.

Chapter Meeting

When: 7 March 2020

Where: Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, near Dulles International Airport

Details: Download Flyer

HERE.

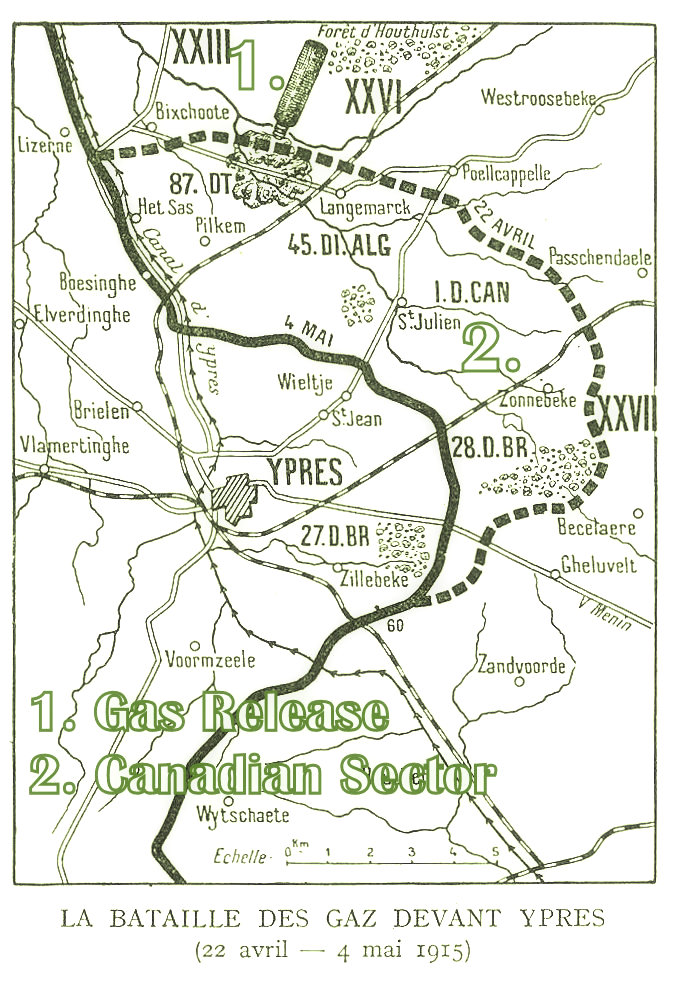

The Gas at Second Ypres: 22 April 1915

German Pioneers Igniting Chlorine Gas Canisters at Ypres

An Excerpt from Distant Thunder: Canada's Citizen Soldiers on the Western Front by Joyce M. Kennedy, PhD.; courtesy of Sunflower University Press

As the morning [artillery barrage of April 22, 1915] wore on, Germans continued to devastate Ypres with shells from heavy guns and howitzers, blowing up roads and bridges. One five-foot, one-ton (42cm) shell landed in the Grand Place, killing about 40 soldiers and civilians in one blast. People streamed out of Ypres, "old men sweating between the shafts of handcarts piled high with household treasures ... aged women or wagons stacked with bedding or in wheelbarrows trundled by the family in turn."

North of the Ypres Salient, German soldiers hunched in their front-line trenches sweltering in the heat. They couldn't release the gas. There was no wind. They waited. Noon came and went. Still, no wind! But finally, in late afternoon, the wind stirred, and some light breezes began to blow southward. The attack could go on! German artillery immediately began to bombard the French lines. Then they opened the valves of the gas cylinders, and the deadly vapors began to drift southward over No Man's Land and onto the unsuspecting French and Algerian troops.

Those receiving the brunt of the attack (the French Territorials, Moroccans, and Algerians) began to flee backwards, sometimes falling, fainting, and vomiting. Many, frothing at the mouth or blinded, could not rise again and lay where they fell, writhing in agony. Some, terrorized and grasping their throats, jumped into trenches or shell holes, the worst possible places to take shelter because the chlorine, being heavier than air, settled in the lower spots. Those who could, ran southward in terror, trying to outrun the noxious suffocating, yellowish-green gas. Because the cloud was drifting south at five or six miles an hour, however, they could not.

Soldiers of 13th (Royal Highlanders of Montreal) Battalion, some of the same troops who had been repairing trenches the night before, were among the first Canadians to notice the peculiar phenomenon — "a cloud of green vapor several hundred yards in length" — over to their left near the French trenches and drifting slowly southward. They were not sure what to make of it. They weren't long in finding out.

Fortunately for the Canadian troops, two medical officers, Lieutenant Colonel George Nasmith of Toronto and Captain F. A. C. Scrimger, a surgeon from the Royal Victoria Hospital of Montreal, were both near Ypres and quickly assessed the situation. Nasmith immediately began working on a chemical solution to the gas problem. Scrimger had a more immediate solution. He told men to urinate on their handkerchiefs or puttees (a long strip of cloth wound spirally around the leg for protection and support) and tie them over their nose and mouth. The action would save many. . .

One soldier of the Canadian Scottish (16th) Battalion, Private Nathaniel Nicholson, recalled seeing people running wildly every which way. "As a matter of fact, I saw one woman carrying a baby and the baby's head was gone, and it was quite devastating."

Later, on 12 July 1915, Robert Kennedy [Father of the author] wrote to Walter Farmer of Cumberland about the fateful day.

I will never forget the night of the 22nd of April. We, part of the ammunition column, had moved up to a farm near St. Julien on the night of the 21st and spent the next day digging dugouts to sleep in, In the afternoon, when I had almost finished mine, we heard rapid fire and in a few minutes could see a haze of greenish-yellow smoke rising up where we knew the trenches were. This was the gas which you have read so much about, but we didn't know It at the time. Soon the shells started coming over, searching for batteries near us big shells and little ones, filling the air with smoke and making one continual roar Finally the gas reached us, but we were too far back for it to do any harm though it made our eyes sore and caused the horses to cough.

We saw the Algerians coming back, but we didn't understand what was really happening. Just as we finished supper we had orders to harness up and hook on. . .

In the late afternoon hours of 22 April, the devastating effects of 168 tons of chlorine gas on front-line troops resulted in a critical gap in the Allied line, though no one seemed to know at the time exactly how great the gap was. The confusion was understandable. With telephone lines disrupted by heavy shelling (wireless radio was not yet in use), initial reports were conflicting. Some indicated that the French had lost all their guns (they had indeed lost 57) and had been driven backward. Several messages around 7 p.m. indicated that the Canadian line had also broken and been forced back as far as St. Julien, northeast of Ypres. There were reports of a gap of 8,000 yards threatening the loss not only of Ypres itself but all Allied troops still holding the Salient.

There were many questions. How great, in fact, was the gap? Was a major rout in the offing? Had the Germans broken through the Canadian line as well? Was the whole Ypres Salient in jeopardy? The answers would take hours to determine. Whatever the case, however, one answer was obvious. The French had suffered a serious setback.

Dead Algerian Gas Victims at Ypres

To be sure, there was confusion at Mouse Trap Farm, headquarters of Major General Turner and his 3rd Brigade. Although not lacking in personal courage (he had won the Victoria Cross in the South African War and now concealed broken ribs to be in the thick of battle), Turner was unable to grasp the overall situation and sent several erroneous messages to the 2nd Brigade and to Division headquarters. To be fair, however, it should be noted that his headquarters were now almost in the front line, and in the midst of shelling and disruption.

Though few knew it, the Canadian line had not broken. Unknown to many on either side of No Man's Land, troops of the 13th (Royal Highlanders of Canada) Battalion were still holding their part of the front line north of St. Julien, immediately to the right of the gassed Algerian Division. At 5 p.m., at the first hint of trouble, their Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Loomis had ordered his men to stand to arms, and take battle positions. They would hold their ground as long as humanly possible, though, with the Algerians having been routed, their left side was now exposed. . .

As word spread about the gas, troops everywhere sprang into action. Several batteries of the Canadian Field Artillery opened fire on the German trenches. About two miles behind the 13th Battalion, the 10th Battery under Major William B. M. King was holding an orchard just 500 yards above St. Julien with four 18-pounder field guns. At about 7 p.m., King peered over a hedge and spotted the helmets of a large group of advancing German soldiers. They had already broken through the line formerly held by the fleeing Algerians just to the left (west) of the 13th Battalion. Worse yet, they could now easily swing in behind the Montreal Highlanders and cut them off. (Some already had, in fact, in wiping out Norsworthy's men.) King's men opened fire, but the Germans quickly dug in. Realizing that only a few isolated pockets of Canadians and Algerians were holding off the enemy, King called for backup support.

Memorial at St. Julien Where Canadian Forces Held the Line

King stubbornly continued to blast away, slowing the German advance. He was detaining them but knew it was only a matter of time until his battery, too, would be overwhelmed. And every time horses hauled up ammunition wagons, they were immediately cut down by enemy fire, stranding the wagons. Work parties then tried to bring up some ammunition by hand.

Rather than try to provide a condensed version of the AEF's experience with gas warfare, I've decided to make available to our readers the U.S. Army's 1984 definitive study on the subject. Its full title is: Chemical Warfare in World War I: The American Experience, 1917-1918. The 112-page pdf document can be downloaded by clicking on the address below.

Finally, some help arrived in the form of 60 more troops, including a 19-year-old machine gunner, Lance Corporal Frederick Fisher of the 13th (Royal Highlanders of Canada) Battalion. Fisher and his four-man volunteer crew hurriedly set up their Colt machine gun, and time and time again drove back the advancing Germans. As Fisher's men were picked off one by one, others rushed in to take their place. Finally, however, he alone was left. Instead of retreating, he stubbornly lugged his gun forward, firing incessantly. His defiance in the face of death brought him the Victoria Cross, the first Canadian in the war to receive the highest of all British military honors. Fisher, however, didn't live to receive it; he was killed the next day. But his heroic actions gave King enough time to pull his guns back to some surviving horses where the men were able to hitch up and retreat into the darkness.

By 9 p.m., less than four hours after the gas had been released, the whole Ypres Salient (including the 50,000 British troops and their 150 guns), was in jeopardy. Then came reports that the Germans had taken St. Julien and Mouse Trap Farm (Headquarters of the 3rd Brigade). By 10:00 p.m., another report indicated that the Germans had moved even closer, taking Wieltje.

Both reports, however, were erroneous. The 3rd Brigade was still holding its front-line trenches, though its situation was becoming increasingly precarious. In fact, the whole Canadian line still held, even though its four and a half battalions were badly outnumbered by two German brigades. But their initial 4,000-yard front now had another 4,000 yards of unprotected front line, which had been left vulnerable when the French and Algerians fled.

Joyce Kennedy's Distant Thunder can be ordered online through Amazon.com.

The Four Types of Gasses

Right Click on Image to See Larger-Sized Map in Separate Window

The American Experience with Chemical Warfare

Soldiers of the U.S. 366th Infantry Receiving Gas Mask Instruction

http://www.worldwar1.com/pdf/uschemicalwarfare.pdf

100 Years Ago:

|

The Future of Chemical-Biological Weapons on the Battlefield

The U.S. Military's Joint Service Lightweight Integrated Suit

You can take the most beat-up army in the world, and if they choose to stand and fight, you are going to take casualties; if they choose to dump chemicals on you, they might even win.General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, 1993 Autobiography

Chemical and biological agents have been a part of human conflict

throughout history. During the Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.) the

Spartans used noxious smoke containing arsenic for attacks against

Athenian-allied cities. During the 14th century, attacking Tartars catapulted

plague-infected cadavers into the city of Kaffa (now Feodosia, Ukraine). The

subsequent outbreak of the plague resulted in the conquest of the city.

Efforts to restrict the use of chemical and biological weapons began with

the Greeks and Romans, who condemned the use of poison in war as a

violation of ius gentium, the law of nations. In recent times, a fundamental

tenet of international law has been that weapons should not be used if their

effects cause. suffering disproportionate to their military utility. The

potential of chemical-biological weapons to cause protracted human suffering

and injury to non-combatants makes them particularly egregious in the eyes

of the law. [Nevertheless] chemical/biological weapons use have occurred in recent years.

Chemical Exposure in Iraq.

Time Magazine, 7 November 2014

[Further] the world is now entering a new era in the history of chemical-biological

weapons. This era began with the biotechnology revolution in the 1970s,

specifically with the advent of genetically engineered agents. Advances in

biotechnology have blurred the distinction between chemical and biological

toxins now that “mid spectrum” agents can be produced, which include

powerful toxins, bioregulators, and physiologically active compounds. As

this technology has advanced, their lethality has increased exponentially.

It is quite likely the threat of the future will be the simultaneous employment

of multiple chemical and biological agents that are engineered to evade

detection and negate vaccines and medicines. . . Chemical

agents include choking, nerve, blood, blister, vomiting, tear, and

incapacitating agents . . . Of additional grave concern is the advent of more potent chemical agents.

Recent examples include two Russian nerve agents that are eight times as

potent as the currently most powerful nerve agent known as “VX.”

When actually placed on a military force, the greatest value of chemical weapons

lies in their capacity to rapidly degrade the effectiveness of the force for a defined

period, and to increase its vulnerability to follow-on conventional attack. For

a poorly prepared force, “even a small and relatively harmless chemical agent

attack can produce results out of all proportion to the efforts involved from

the attacker.”

The U.S. Army Chemical and Nuclear Exercises

demonstrated that the mere wearing of protective gear leads to additional

casualties, loss of unit efficiency, reduced operational tempo, and degraded

operational effectiveness. Finally, the psychological impact of chemical

weapons use may also be militarily significant. The terror effect of such

weapons may drive “troops who feel they are defenseless ... to break and

run after minimal losses.”

Arms Control Today, March 2019 Report

Source: Excerpted from "Chemical-Biological Attack: Achilles

Heel of the Air Expeditionary Force?," by Byron C. Hepburn, Colonel, USAF

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications |

||

Order Our

|

Shop at |

Order the Complete Collection

|

A World War One Film Classic

Uomini Contro [translated: Men Against] is a 1970 WWI film that was retitled Many Wars Ago for its international release. Prolific Italian director Francesco Rosi's film is set around Monte Fior, a peak overlooking Italy's Asiago Plateau, which–like Hamburger Hill in the Vietnam War–was, for a brief period, considered critical to capture and hold by the high command. The story is taken from an outstanding semi-fictional account of the war on the Italian Front, A Year on the Altopiano (alternately, The Sardinian Brigade) by Emilio Lusso. Rosi's script seems also to have been heavily influenced by Stanley Kubrick's Paths of Glory. I'll not expand on that point, though, to avoid giving too much of the plot away.

The movie is magnificently photographed and the filming location was a near-perfect match for the actual site. The set and costume designers also did a superb job. The battles are all shot strictly from the Italian point of view, so the Austrian enemy is rarely viewed and not at all demonized. The villains of the piece are up the chain of command: the major commanding the battalion, the regiment's colonel, and divisional commander General Leone, are all caricatured as ambitious, indifferent, and reckless with their men's lives. All in all, I found Uomini Contro an exciting but powerfully tragic anti-war film, with a realistic portrayal of the combat on the oft-forgotten Italian Front. Available on DVD from Amazon.com and for streaming on Amazon Prime.

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon