March |

Access |

Fall of an Empire:

|

A Benign Franz Josef in Poster

|

|||||

Free Publications |

||

|

Amazon.com |

||

Comparing the Falls of the Romanov and Habsburg Dynasties

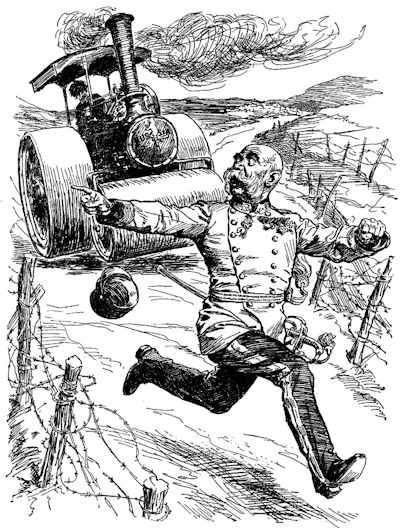

The Emperor Fleeing the Russian Steamroller (Punch)

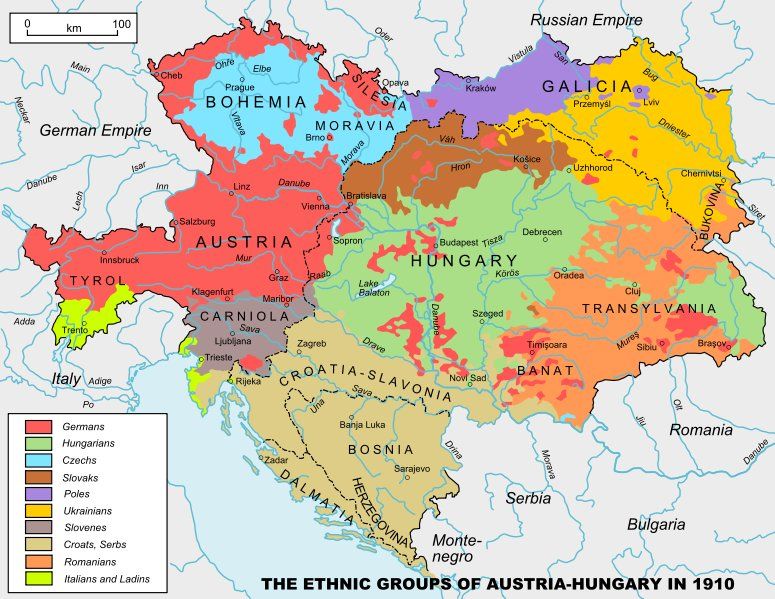

In October 1918, there was an armed uprising in Budapest, and Czechoslovakia declared independence, all of which marked the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. On the territory of the former Austria-Hungary arose the Republics of Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary and Yugoslavia (and a number of territories became part of Romania and Italy).

Source: Bystudin, 11 April 2020

Russia, as a result of the February and October revolutions, separately withdrew from the war on extremely unfavorable terms, and the Brest peace was concluded. In 1917, Russia was no longer able to fight, which allowed Germany to continue the war for another year. During the revolution of 1917, the Russian monarchy was overthrown. On the territory of the former Empire, several independent States were formed-Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Estonia, Finland, the Belarusian People’s Republic and the Ukrainian People’s

Republic—the latter two soon joined the USSR.

What was common between the collapse of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires was that it occurred during the First World War and during armed uprisings.

The difference is that the failure of the Provisional Government to resolve pressing issues led to the October revolution and a separate peace, while there was no deepening of the revolution on the territory of Austria-Hungary.

Perhaps the reason for the differences was that in the Russian Empire, the revolution took place earlier than in Austria-Hungary by a year.

The Habsburg Empire Before the War

Vienna in La Belle Epoque

In those days before the Great War when the events narrated in this book took place, it had not yet become a matter of indifference whether a man lived or died. When one of the living had been extinguished another did not at once take his place in order to obliterate him: there was a gap where he had been, and both close and distant witnesses of his demise fell silent whenever they became aware of his gap. When fire had eaten away a house from the row of others in a street, the burnt-out space remained long empty. Masons worked slowly and cautiously. Close neighbors and casual passers-by alike, when they saw the empty space, remembered the aspect and walls of the vanished house. That was how things were then. Joseph Roth,

Everything that grew took its time in growing and everything that was destroyed took a long time to be forgotten. And everything that had once existed left its traces so that in those days people lived on memories, just as now they live by the capacity to forget quickly and completely. . .

He was an old man from an old era. The old men from the era before the Great War may have been more foolish than the young men of today. But in the moments that preceded those horrible ones and that in our time might be shrugged off with a casual joke, the old decent men maintained heroic equanimity. Nowadays the concepts of honor—professional, familial, and personal—that Herr von Trotta lived by seem like relics of implausible and juvenile legends. But in those days an Austrian district captain like Herr von Trotta would have been less shaken by the news of the sudden death of his only child than by the news of even a seemingly dishonorable action of that only child.

That lost era, which was virtually buried under the fresh grave mounds of the fallen, was ruled by very different notions. If someone offended the honor of an officer of the Imperial and Royal Army, and that officer failed to kill the man apparently because he owed him money, then that officer was a misfortune and worse than a misfortune: he was a disgrace to his progenitor, to the army, and to the monarchy.

Radetzky March

The Danube at Budapest

The Fall of an Empire:

1918: The Emperor's Army Crumbles

Optimistic-Looking Austrian Soldiers Before the Battle of the Piave

1918: The Emperor's Army Crumbles

In early 1918, Germany seemed to be riding high. Unable to resist Wilhelm's pressure, Emperor Karl pledged a two-pronged attack from Asiago in the north and across the River Piave toward Venice. Karl's promise of a two-pronged offensive flew in the face of warnings that Field Marshal Borojevic (his new rank) had sent to the high command since the end of March. Karl and his chief of staff hoped to make Rome negotiate and enlarge their spoils when Germany won the war. Borojevic did not believe the Central Powers could win. Instead of wasting its strength on needless offensives, Austria should conserve it to deal with the turmoil that peace would unleash in the empire.

The bombardment began at 03:00 on 15 June. As at Caporetto, the Austrians aimed to incapacitate the enemy batteries with a pinpoint attack, including gas shells. However, their accuracy was poor, due to Allied control of the skies; many of the shells may have been time expired, and the Italians had been supplied with superior British gas masks. Nevertheless, the morning went well; the Austrians moved 100,000 men across the river under heavy rain. Watching the infantry pour over the pontoons, Jan Triska and his gunners wondered if this time they would reach Venice. Enlarging the bridgeheads proved more difficult. Progress was made on the Montello, where the four divisions pushed forward several kilometers, and around San Donà, near the sea. Elsewhere, the attackers were pinned down near the river. Farther north, Conrad's divisions attacked from Asiago toward Monte Grappa. Slight initial gains could not be held; the Italians had learned how to use the "elastic defense," absorbing enemy thrusts in a deep system of trenches, then counterattacking

Progress on the second day was no easier. Conrad was in retreat; his batteries—more than a third of all the Habsburg guns in Italy—were out of the fight. Borojevic ordered his commanders to hunker down while forces were transferred from the north. Meanwhile, the Piave rose again, washing away many of the pontoons. Supplying the bridgeheads across the torrent became even more dangerous. The Austrians were too close to exhaustion and their supplies too uncertain for a sustained battle to run in their favor.

Borojevic told the emperor that if the Montello could be secured, it should be the springboard for a new offensive. Securing it would need at least three more divisions, including artillery. If the high command did not intend to renew the offensive from the Montello, it was pointless to retain the bridgeheads; they should be abandoned and all efforts dedicated to strengthening the defenses east of the river. As Karl wondered what to do, the German high command stepped in, ordering a cessation of hostilities so that the Austrians could dispatch their six strongest divisions to the Western Front, for Ludendorff's spring offensives were running out of steam and 250,000 American troops were arriving every month. Karl consulted his commanders in the field, who echoed Borojevic's stark choice: either reinforce or withdraw. Then he consulted his chief of the general staff, General Arz von Straussenberg. A new offensive within a few weeks was, they agreed, not a realistic prospect. Their reserves were almost used up; even if enough divisions could be transferred to the Piave from elsewhere—and none could safely be spared from Ukraine or the Balkans—the Italians would match them. It would not be possible to recapture the zest of 15 June without a lengthy recovery.

The Piave and Vittorio Veneto: Decisive Battles of the Italian Front

Late on the 20th, Karl ordered the right bank of the Piave to be abandoned. General Goiginger, commanding the corps that had performed so well on the Montello, refused to obey. They had taken 12,000 prisoners and 84 guns; how could they retreat? Eventually he submitted, and the withdrawal began. Both sides were exhausted, and the maneuver was completed without much fighting. The Bosnians and Hungarians on the Montello worked their way back to the river. The last Austrians crossed on 23 June, ending the Battle of the Solstice. The Italians had lost around 10,000 dead, 35,000 wounded, and more than 40,000 prisoners, against 118,000 Habsburg dead, wounded, sick, captured, and missing. Early in July, Third Army units capped the achievement by seizing the swampy delta at the mouth of the Piave, which the Austrians had held since Caporetto. For many soldiers, the Battle of the Solstice cleansed the stain of Caporetto, and the name of the Piave has ever since evoked a glow of fulfillment. For Emperor Karl's army, defeat triggered demoralization, desertions in the ranks, and talk of mutiny among the non-Germanic troops.

Despite the resounding defeat of the Austro-Hungarians at the Battle of the Piave River in June 1918 the cautious Italian chief of staff Armando Diaz hesitated to press home his advantage over the Austro-Hungarians, preferring to confine the army to local operations. This was despite appeals from both Ferdinand Foch–the Allied Supreme Commander–and Lord Cavan, commander of British forces in Italy. However, the advancing successes of Italy's allies on the Western Front—which effectively ruled out German assistance to their Austro-Hungarian allies on the Italian Front (with the Germans themselves requesting assistance in France)–brought about a change of heart. The Italian government, keen to ensure the maximum territorial gains ahead of the ensuing peace conference, added to the chorus of pressure upon Diaz. Thus, he resolved to launch a combined offensive. A primary assault would be launched on the Piave, intended to advance upon Vittorio Veneto.

The attack opened on 23 October 1918 with an Italian advance in the mountains. The extent of Austro-Hungarian resistance surprised Diaz, however, and succeeded in preventing any significant Italian gains, although the Austro-Hungarians were obliged to bring up reserves from the Lower Piave. Such reserves could be ill afforded given that the main Italian advance began the same day in the Lower Piave.

Lord Cavan's Tenth Army succeeded in capturing Papadopoli Island two days later, on 25 October. On 27 October his force was again in the fore, succeeding—in spite of a river flood—in establishing a bridgehead across the river, meeting with relatively light Austro-Hungarian resistance. Some 24 km farther north, Twelfth Army, led by General Graziani, also crossed the river and likewise established a bridgehead; Eighth Army followed to Graziani's right. Shortly afterward, Cavan dispatched two detachments to clear the river of remaining Austro-Hungarian resistance, after which the bridgeheads were joined. With Cavan's main force pushing ahead on 27 October, the Austro-Hungarian Fifth Army was forced back. Three days later the Italian Third and Tenth Armies succeeded in reaching the River Livenza and Eighth Army took the primary target of Vittorio Veneto, thereby splitting the Austro-Hungarian armies.

With the Allies succeeding in advancing 24 km along a 56km front, a truce was finally agreed on 2 November with the capture of Tagliamento; an armistice came into effect the following day, signed at Padua. Hostilities were concluded on 4 November.

Defeated Forces Retreating During Vittorio Veneto

A resounding success for the Allies, Vittorio Veneto finished the Austro-Hungarian army as a fighting force. The Italians lost some 38,000 casualties, a figure dwarfed by the 300,000 prisoners suffered by the Austro-Hungarians. In the wake of the at Vittorio Veneto, minorities, subject to powerful propaganda efforts by the allies, ultimately refused to go on fighting for a dynasty that had lost its last unifying figure two years earlier with the death of Emperor Francis Joseph Simultaneous political turmoil [discussed below] completed the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Sources: Roads to the Great War; Firstworldwar.com

The Fall of an Empire:

The Dissolution of Austria-Hungary

The Dissolution of Austria-Hungary

Independent Czechoslovak State Declared: 28 October 1918

The duality of the Habsburg monarchy had been underlined from the very beginning of the war. Whereas the Austrian parliament, or Reichsrat, had been suspended in March 1914 and was not reconvened for three years, the Hungarian parliament in Budapest continued its sessions, and the Hungarian government proved itself constantly less amenable to dictation from the military than had the Austrian. The Slav minorities, however, showed little sign of anti-Habsburg feeling before Russia's March Revolution of 1917. In May 1917, however, the Reichsrat was reconvened, and just before the opening session the Czech intelligentsia sent a manifesto to its deputies calling for "a democratic Europe…of autonomous states." The Bolshevik Revolution of November 1917 and the Wilsonian peace pronouncements from January 1918 onward encouraged socialism, on the one hand, and nationalism, on the other, or alternatively a combination of both tendencies, among all peoples of the Habsburg monarchy.

Early in September 1918, the Austro-Hungarian government proposed in a circular note to the other powers that a conference be held on neutral territory for a general peace. This proposal was quashed by the United States on the ground that the U.S. position had already been enunciated by the Wilsonian pronouncements (the Fourteen Points, etc.). But when Austria-Hungary, after the collapse of Bulgaria, appealed on 4 October for an armistice based on those very pronouncements, the answer on 18 October was that the U.S. government was now committed to the Czechoslovaks and to the Yugoslavs, who might not be satisfied with the "autonomy" postulated heretofore. The emperor Karl had, in fact, granted autonomy to the peoples of the Austrian Empire (as distinct from the Hungarian Kingdom) on 16 October, but this concession was ignored internationally and served only to facilitate the process of disruption within the monarchy: Czechoslovaks in Prague and South Slavs in Zagreb had already set up organs ready to take power.

Revolution in Hungary, 31 October 1918

The last scenes of Austria-Hungary's dissolution were performed very rapidly. On 24 October (when the Italians launched their very timely offensive), a Hungarian National Council prescribing peace and severance from Austria was set up in Budapest. On 27 October, a note accepting the U.S. note of 18 October was sent from Vienna to Washington—to remain unacknowledged. On 28 October the Czechoslovak committee in Prague passed a "law" for an independent state, while a similar Polish committee was formed in Kraków for the incorporation of Galicia and Austrian Silesia into a unified Poland. On 29 October, while the Austrian high command was asking the Italians for an armistice, the Croats in Zagreb declared Slavonia, Croatia, and Dalmatia to be independent, pending the formation of a national state of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs. On 30 October the German members of the Reichsrat in Vienna proclaimed an independent state of German Austria.

The solicited armistice between the Allies and Austria-Hungary was signed at the Villa Giusti, near Padua, on 3 November 1918, to become effective on 4 November. Under its provisions, Austria-Hungary's forces were required to evacuate not only all territory occupied since August 1914 but also South Tirol, Tarvisio, the Isonzo Valley, Gorizia, Trieste, Istria, western Carniola, and Dalmatia. All German forces should be expelled from Austria-Hungary within 15 days or interned, and the Allies were to have free use of Austria-Hungary's internal communications and to take possession of most of its warships

Postwar Central Europe, 1920

Count Mihály Károlyi, chairman of the Budapest National Council, had been appointed prime minister of Hungary by his king, the Austrian emperor Karl, on 31 October but had promptly started to dissociate his country from Austria-partly in the vain hope of obtaining a separate Hungarian armistice. Karl, the last Habsburg to rule in Austria-Hungary, renounced the right to participate in Austrian affairs of government on 11 November, in Hungarian affairs on 13 November. Source: Encyclopedia Britannica

100 Years Ago:

|

A 21st Century Memorial on the

Passchendaele Battlefield

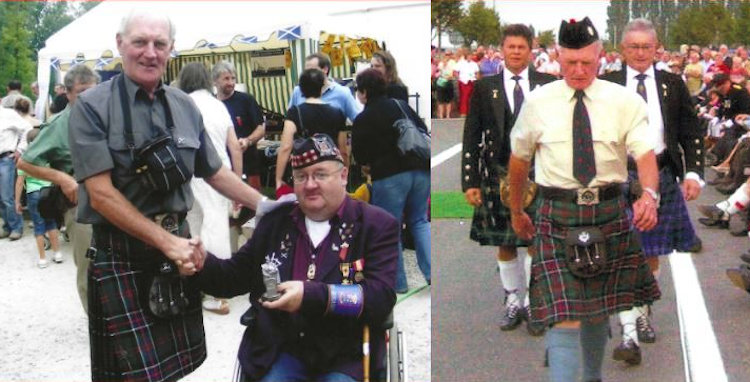

Scottish Memorial, Frezenberg Ridge

On 25 August 2007 the above monument was dedicated on Frezenberg Ridge—just 2.5 miles northeast of the Menin Gate on the Ypres battlefield.

Between 31 July and 10 November 1917 the 9th, 15th Scottish Divisions and the 51st Highland Division were all engaged in the Third Battle of Ypres—better known today as Passchendaele. In addition, many Highland and Lowland battalions served in mixed British divisions. In the account below, Tom Jenkins, one of the individuals who made this major memorial happen, will help us tell the story of how this tribute to the Scottish sacrifices during the Great War came about.

2007 Dedication Ceremony

The site that was chosen is of great historical significance for the Scottish forces that fought here in 1917. The 15th Scottish Division fought here in the opening days of the battle, and the 9th Scottish (inclusive of a South African Brigade) fought on the northern edge of the ridge later in the struggle. Late in the planning/funding cycle, the Scottish government declined to contribute the final block of financing to complete the project. Our contributor here, Tom Jenkins, took it upon himself to raise the money. As an organizer of annual Robert Burns dinners, he made an appeal at 20 different events. In a few weeks he raised £5,000, allowing construction to proceed. Here Tom gives the background of how the effort got started.

John Thomson, Inspiration for Creating a Scottish Memorial

Now, how did the monument come about? Well in 1998 a Belgian family was cultivating its garden and came upon the remains of three soldiers. The Commonwealth War Graves office in Ypres was contacted and on inspection, they confirmed that it was a battlefield burial as they were very decently interred. Sadly, only one man could be identified. By his uniform, he was a Gordon Highlander and in possession of some I.D. He was Private John R. Thomson from Lochgelly in Fife.

Tom Jenkins Honored for His Contribution to Building the Memorial

On 21 October 2004, Thomson and his fellow soldiers were buried at the nearby Polygon Wood Cemetery. As the Gordon Highlanders had been disbanded a burial party from the Royal Regiments of Scotland was formed.

Following the burial, the men of the burial party were given a guided tour of the Ypres battlefield, Tyne Cot Cemetery, and the Menin Gate. At the end of the tour, one young Scottish soldier of the burial party asked if he could now be taken to a Scottish monument. Strangely enough, nowhere on the Western Front can be found a monument commemorating Scotland's involvement and sacrifices in the war. Due to the finding of Pvt. John Thomson's remains and the request that young soldier made, a decision was made to rectify the matter and the rest is, of course, history.

The Memorial Park Today

The monument was unveiled on 25 August 2007, the 90th anniversary of an attack on the ridge by Scottish regiments. The monument is a Celtic cross, sculptured from pink Correnie granite and was made by an Aberdeen company, Glenrock Fyfe. The base was built with concrete blocks excavated from the original trenches by local tradesmen who were paid by the Zonnebeke council. Ten years later for the centenary of the Battle of Passchendaele, the site around the monument was enlarged and landscaped, and enhanced with life-sized metal cut-outs of kilted soldiers advancing toward Passchendaele.

A World War One Music Video

This is the chorus of the 1914 British hit song "Til the Boys Come Home" which was later changed to Keep the Home Fires Burning. The music was written by Welsh-born David Ivor Davies (1893-1951) (above, right), then professionally known as Ivor Novello (he officially changed his name by deed poll in 1927). In places, the very sing-able tune bears a resemblance to the 1906 Christmas carol "In the Bleak Mid-Winter" by Gustav Holst (1874-1954). The tear-jerking lyrics were attributed to an American, Lena Guilbert (Brown) Ford (1870-1918) (above, left), who was a friend of Novello's mother Clara (Novello) Davies (1861-1943), although there has been unfounded speculation that Mrs. Davies actually penned them.

Commentary by James Patton

Keep the Home Fires Burning,

While your hearts are yearning,

Though your lads are far away

They dream of home.

There's a silver lining

Through the dark clouds shining,

Turn the dark cloud inside out

'til the boys come home.

"Keep the Home Fires Burning" was the first of a long string of hits for Novello. It was also the first and only notable success for Mrs. Ford. Unlike some other popular songs of the era, like "Tipperary" or "Long, Long Trail", this one is about patriotism, defense of what we hold dear, glorious service, and keeping a stiff upper lip. It is reflective of the 1914 "Rah-Rah" spirit in the UK that led to huge enlistment numbers and the short-war myth.

Novello's mother was from a musical family and she was a well-known singer, voice teacher, choral conductor, and composer (under a pseudonym) of Welsh choral music. Her son's vocal talent was also evident at an early age, and it was arranged for him to study at the cathedral in Gloucester. Novello published his first song in 1908 before he received a choral scholarship to Magdalen College, Oxford. In 1913 he became a protégé of the noted patron of the Arts Sir Edward Marsh (1872-1953) KCVO CB CMG, who was a close colleague of Winston Churchill. In 1916 Novello joined the Royal Naval Air Service, where he washed out of pilot school after crashing two training aircraft, and Sir Edward arranged for a post at the Admiralty for the duration. While performing this service Novello wrote a number of songs and two musicals.

After the war Novello shifted to acting, making his movie debut in 1920 and his stage debut in 1921. He appeared in 22 movies (only one was American), but in 1934 he returned exclusively to the theater, acting in and writing plays and musicals. During the 1930s he wrote and starred in four long-running West End musicals, and also starred in many shows, mostly plays.

During WWII he wrote and starred in two more long running musicals but was sidetracked by serving a prison sentence for the misuse of petrol coupons. After the war, there were two more smash hit musicals, although the initial run of his last was cut short by his sudden death after a performance.

In 1956 the Academy of Songwriters, Composers, and Authors (BASCA) established the Ivor Novello Award for Songwriting and Composition, popularly known as the "Ivor," for which only British and Irish artists are eligible. An Ivor is a small solid bronze sculpture of Euterpe, the muse of lyric poetry. Currently, there are 24 categories, and over 1,000 Ivors have been awarded since inception. The BASCA changed its name to The Ivor Academy in 2009.

Lena (Brown) Ford was born in Venango County, in the western Pennsylvania oil fields. In 1887 she graduated from Elmira College in New York (then female only) and married Dr. Harry Ford. In 1898 she moved to London with her mother and son Walter (1888–1918) to pursue her music. Among her other published works are "When God Gave You to Me", "We Are Coming, Mother England" and "God Guard You" (with Westell Gordon). Her career was cut short when, during the night of 7 March 1918, Lena and Walter Ford became the first American civilians to be killed in a German air raid.

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon