April

2019 |

|

|

|

Detail: Turkish Memorial, Gallipoli Battlefield

Just down below you will see a photograph of your esteemed editor on the Asian side of the entrance to the Dardanelles standing–-so I was fantasizing at the time–in the footsteps of such legendary notables as Achilles and Alexander the Great. This was the occasion of the first of my two visits to the Gallipoli battlefield in 2009 and 2010. A decade ago, I was still searching for a solution to that imponderable WWI mystery: just what went wrong with the most imaginative plan ever devised for breaking the trench-deadlock on the Western Front? Did the admirals lose their nerve? Shouldn't the Allies have started the land and naval assaults together? Was that Mustafa Kemal guy the luckiest guy on earth, or what?

After digesting what I saw of the battlefield up close, though, I had a new idea, and every day since, I've come to feel stronger about it. The Dardanelles Campaign was a bad idea and should never have been attempted. I have written in detail why I concluded this, HERE and

HERE,

but for now, I'd like to suggest our readers–especially those who are convinced that good things might have happened, if everyone had just done their jobs right, and then all those boys wouldn't have died in vain–check out how the Turks view the whole Dardanelles campaign. Click on some of the links we've provided over in the right column. Their ancestors on the scene had a winning hand to play and knew that they had things under control by 18 March 1915–over a month before the first Tommies and Diggers hit the beach. To paraphrase Nobel Laureate Mr. Bob Dylan a little, once the grand venture was set in motion, "It was gonna be a hard rain that fell on Gallipoli in 1915." MH

At the Dardanelles, 2009

America's Siberian Intervention: Part 1 of 4,

Why?

A Czech Legion Train Passing Through Siberia

It was a war few Americans knew about then or now. Orchestrated behind closed doors, inspired by panic, and plagued by futility, America's military intervention in Siberia during the First World War continued long after the Armistice sent the Doughboys in France home. President Woodrow Wilson considered the order to send American troops to Siberia, a region besieged by civil war, lawlessness, and murder, one of the most difficult decisions of his presidency.

President Woodrow Wilson's motivation for sending troops to Siberia stemmed from the same desires that drove him to try to impose the Paris Peace Treaty on Europe–the promotion of democracy and self-determination. But first and foremost, he wanted to protect the billion-dollar investment of American guns and equipment along the Trans-Siberian Railway. Vast quantities of supplies had been sent when America believed that Russia was capable of fighting and winning against the Central Powers in the spring of 1917.

The Menshevik Revolution, which overthrew the tsar in February and March 1917, raised Wilson's hopes for democratizing Russia and implanting capitalism there. Under Alexander Kerensky's regime, the first wave of American technicians arrived to revamp and run the vast Trans-Siberian Railway. The European allies, in concert with Kerensky, agreed to establish the American-run Russian Railway Service. Beginning in November 1917, the United States provided Russia with 300 locomotives and more than ten thousand railway cars. Bad weather and an unfavorable political climate delayed the final entry of the Russian Railway Service Corps until March 1918, when they entered Siberia from the Manchurian city of Harbin

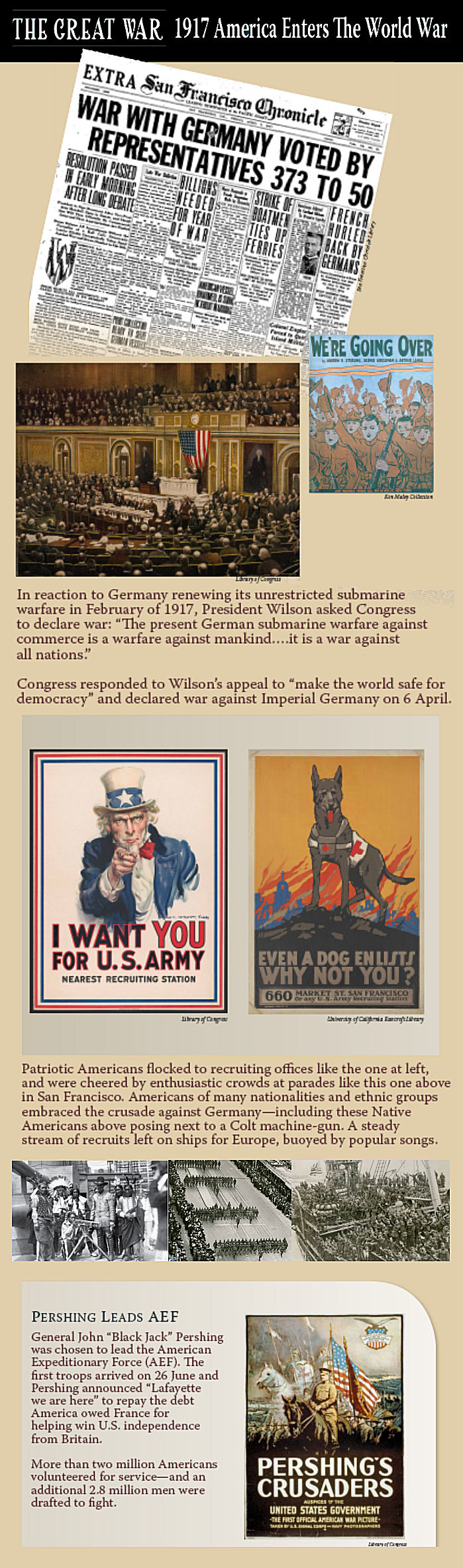

President Wilson at His Desk

In addition to the supplies and the presence of Americans attempting to fix and develop Russia's railway service, Wilson also considered the Czech Legion. The Legion had been formed early in 1918 from Czech and Slovak prisoners of war in Russia, sympathetic Russian Slavs, and deserters from the Austro-Hungarian Army. Beginning in March 1918, 40,000 soldiers fought with the Legion for the Allied cause. When the Bolsheviks pulled out of the war, they agreed to let the Czech Legion leave Russia. President Wilson wanted the world to know that the United States supported the safe return of the Czech Legion to its newly formed homeland.

In March 1918, the Legion moved steadily eastward along the Trans-Siberian Railway. When the Bolsheviks tried to disarm the Czechoslovaks, the soldiers of the Legion hid their weapons, and relations between the two groups frayed.

In May 1918 the Red Guard arrested several Czechoslovaks after a confrontation between legionaries and German prisoners of war at Chelyabinsk Station. A Czech had been killed, and his comrades retaliated by lynching a prisoner. The legionaries forcibly released the prisoners and took over the town. In a valiant effort to fight their way back to their homeland, the Czech Legion smashed its way both east and west, toppling just about every Soviet government in the far eastern part of Russia and Siberia.

This dramatic turn of events brought the fate of the Czech Legion to the attention of Wilson and ultimately led to the American intervention in Siberia. In June 1918, Wilson received a number of diplomatic visits directly related to the Allied demand for intervention in Russia. Both the French and British military missions to Russia sent representatives to persuade him to send American troops to Siberia. The War Department had been studying the issue for some time, but they were hardly as sanguine as the French and British wished. The Europeans sought at least 30,000 American troops in Siberia to go in alongside some 60,000 Japanese. The Allies stressed the need to deprive the Germans of access to the billions of dollars' worth of assets that lay strewn about the Siberian landscape. The bulk of the effort was to persuade the Czechs to remain in Siberia as a serious counterweight to the Germans. The Allies hoped that by keeping pressure on the Red Army, they could prevent an alliance between the Bolsheviks and the Central Powers, which they feared might allow Germany and Austria to shift valuable men and material to the Western Front.

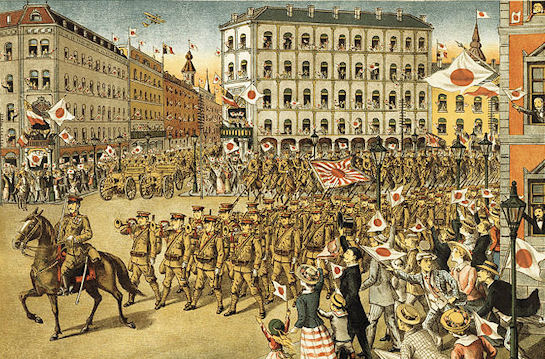

Finally, on 6 July 1918, Wilson decided to intervene in Siberia. The mandate for 8,000 American troops and 70,000 Japanese troops used the rationale of protecting the supplies and communications (the Trans-Siberian Railway) and aiding the Czech Legion in its quest to return home.

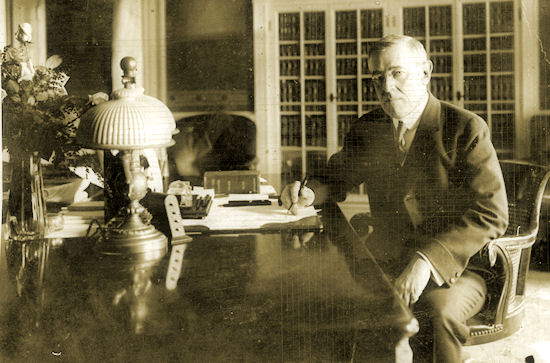

Japanese Forces Arriving in Vladivostok

To lead U.S. forces in Siberia, the War Department turned to Major General William S. Graves, an intelligent and experienced officer training Eighth Division recruits at Camp Fremont, California for duty in France. On 2 August 1918, Graves received a mysterious message from the War Department ordering him to take the first train directly to Kansas City. At the train station, Secretary of State Newton D. Baker handed Graves an unsigned copy of the Aide Memoire: "This is the policy of the United States in Russia which you are to follow. Watch your step; you will be walking on eggs loaded with dynamite." Graves was now Commander of the AEF, Siberia.

The Japanese had landed the first contingents of more than 70,000 soldiers in June and July and consolidated their control of the Chinese Eastern Railway and much of northern Manchuria near Semenoff's headquarters in Chita. Japanese designs on Manchuria and Siberian economic resources required that no stable government be permitted to develop. To keep the region unsettled, the Japanese could gain leverage in the area by fomenting trouble via Cossack bandits. From the outset, the Japanese cultivated Semenoff and likeminded Cossacks, and lavish gifts and money found their way to Chita and to strongholds of other atamans in eastern Siberia.

Although General Graves did not arrive in Siberia until 4 September 1918, some American troops had arrived as early as 15 August 1918, and quickly took up guard duty along segments of the railway between Vladivostok and Nikolsk in the north.

Sources: Guarding the Railroad, Taming the Cossacks, U.S. National Archives; AEF Siberia, The Doughboy Center

Calling a Time-Out to Revolution

Returning German Troops from Africa Passing Through Berlin's Brandenburg Gate Led by Legendary Commander

Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, 2 March 1919

|

|

The Turkish View

of Gallipoli

As far as the Turkish army is concerned, it was the bloodiest campaign of the Great War. . . Our Nation and History cannot refuse to celebrate this wonderful victory, and express its admiration to all soldiers and officers who participated in it.

Official Turkish Report

Dardanelles/Gallipoli: Overview from the Turkish Viewpoint

Dardanelles/Gallipoli: Overview from the Turkish Viewpoint

Gallipoli's Place in Turkish History (PDF)

Gallipoli's Place in Turkish History (PDF)

With the Turks at the Dardanelles by Arthur Ruhl

With the Turks at the Dardanelles by Arthur Ruhl

The Meaning of Gallipoli to Today's Turks

The Meaning of Gallipoli to Today's Turks

Key to Victory: Defeating the Naval Assault of 18 March 1915

Key to Victory: Defeating the Naval Assault of 18 March 1915

Rewriting the history of Gallipoli: a Turkish Perspective

Rewriting the history of Gallipoli: a Turkish Perspective

Smithsonian Looks at Gallipoli

Smithsonian Looks at Gallipoli

Photos of the Turkish Defenders of the Dardanelles

Photos of the Turkish Defenders of the Dardanelles

Gallipoli 2015: Through 'Enemy Eyes'

Gallipoli 2015: Through 'Enemy Eyes'

Eight on Gallipoli

It is no longer possible to force the Dardanelles . . . Nobody would expose a modern fleet to such perils.

Winston Churchill, 1911

It looked as if no human power could withstand such an array of might and power", [but yet the Turks did].

A Forgotten British Officer

Early morning: Almighty God, Watchman of the Milky Way, Shepherd of the Golden Stars, have mercy upon us. . . Thy will be done. En avant [forward] — at all costs — en avant.

Expedition Commander Sir Ian Hamilton, Diary Entry, 25 April 1915

Men, I am not ordering you to attack. I am ordering you to die. In the time that it takes us to die, other forces and commanders can come and take our place.

Mustafa Kemal, Commander 19th Division, Later the Same Day

The Turkish positions only get stronger every day. … They are magnificently well-led, well-armed and very brave and numerous.

Reverend O. Creighton, Chaplain,

29th Division

Our life here is truly hellish. Fortunately, my soldiers are very brave and tougher than the enemy.

Mustafa Kemal, 20 July 1915

As long as wars last, the evacuation of Suvla and Anzac will stand before the eyes of all strategists as a hitherto unattained masterpiece.

Military correspondent, Vossiche Zeitung, January 1916

O! The rough cliffs witnessed that day

O! The heroic trenches of Sergeant Mehmet

O! The sacred site of Mustafa Kemal

O! The Bloody hills, burnt places.

Mehmet Emin Yurdakul,

"The Epic of the Army"

Despite my retirement from the business, there will still be possibilities for you to visit the battlefields of the Great War.

2019

AEF Battlefields

From: Valor Tours, Ltd. / Mike Grams, Tour Leader

When: September 2019

Details: Request brochure via Email

HERE.

Gallipoli

From: National World War I Museum / Clive Harris & Mike Sheil, Tour Leaders

When: October 2019

Details: Itinerary and Tour FAQ

HERE.

27 April 2019, 10am: League of World War I Aviation Historians Meeting at the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. Details

HERE.

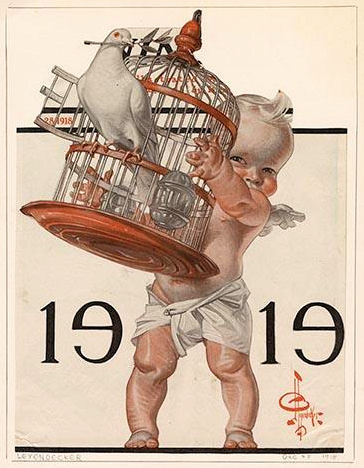

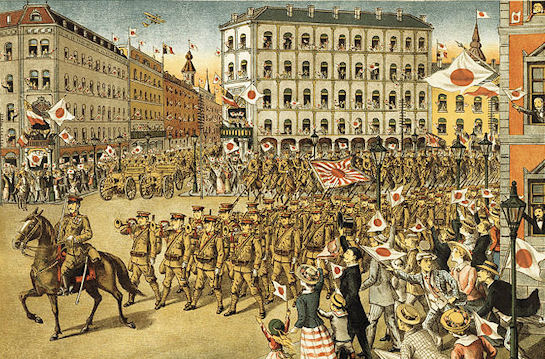

1919 Peace?

Saturday Evening Post Cover Image

From April 2019 – March 2020 the National World War I Museum and Memorial, in Kansas City, MO, will be presenting an exhibition examining how and why "the war–nor its lasting effects–did not end even with the signing of the Treaty of Paris at Versailles."

To commemorate the Centennial of the signing of the Treaty of Versailles and to celebrate American philanthropy before and after World War I a Versailles Palace Dinner will be held in the palace's magnificent Hall of Battles on 28 June 2019. Proceeds from the event will be dedicated to building America's National WWI Memorial at Pershing Square. For information email

HERE

During the eight-month Gallipoli campaign 130,672 soldiers lost their lives:

86,629 Turks

21,255 British

9,878 French

8,709 Australians

2,701 New Zealanders

1,500 Indians

After the Battle of the Somme, author Robert Graves's mother received this letter.

DEAR MRS. GRAVES,

I very much regret to have to write and tell you your son has died of wounds. He was very gallant, and was doing so well and is a great loss. He was hit by a shell and very badly wounded, and died on the way down to the base I believe. He was not in bad pain, and our doctor managed to get across and attend him at once. We have had a very hard time, and our casualties have been large. Believe me you have all our sympathy in your loss, and we have lost a very gallant soldier. . .

Robert Graves, of course, lived until 1985, long enough to see his novel I, Claudius presented on BBC television.

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

Click on Image to Visit

|

|

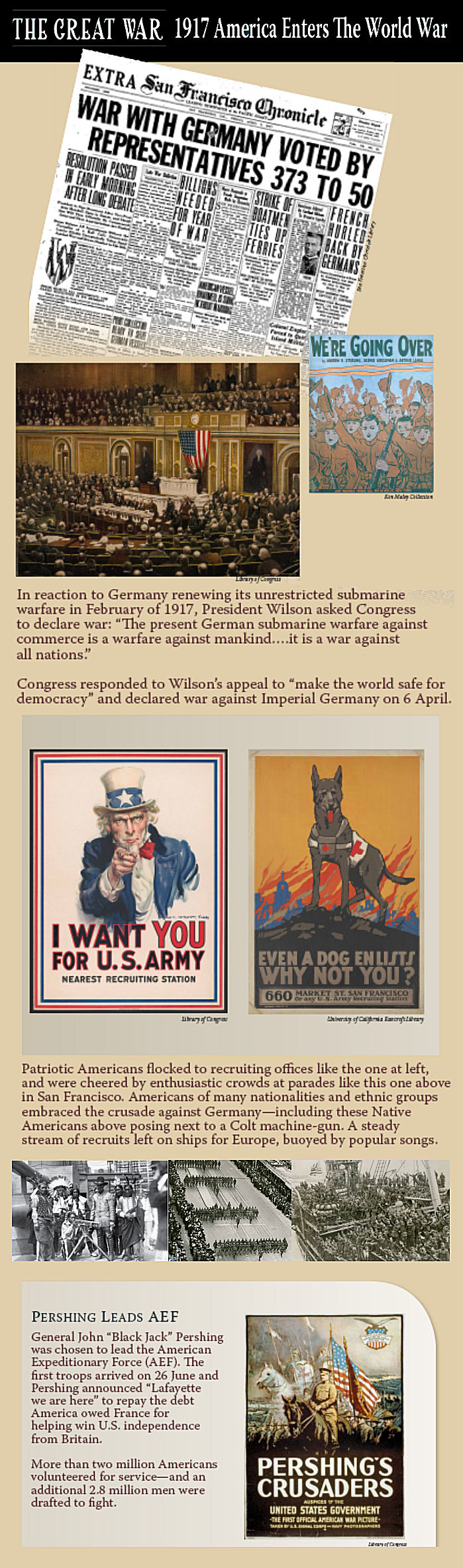

Looking Back: A Retrospective of the War

Part IV

This is our fourth historic banner provided by the San Francisco War Memorial's World War I Armistice Centennial Commemorative Committee. Visit HERE to learn more about the commemorative exhibition being held in the City by the Bay.

Germany Surrenders Her U-boat Fleet

A German U-boat Surrendering to a British Ship

The terms of the Armistice were, in many ways, punitive to the Germans. In part, the British and French sought through the Armistice to disarm Germany, in a misguided attempt to ensure that there would be no further outbreaks of "German militarism." This was clear in the naval terms of the Armistice–particularly with regard to submarines, which were to be surrendered in totality. Article XXII of the agreement instructed the German government thus:

To surrender at the ports specified by the Allies and the United States all submarines at present in existence (including all submarine cruisers and mine layers), with armament and equipment complete. Those that cannot put to sea shall be deprived of armament and equipment and shall remain under the supervision of the Allies and the United States. Submarines ready to put to sea shall be prepared to leave German ports immediately on receipt of a wireless order to sail to the port of surrender, the remainder to follow as early as possible. The conditions of this article shall be completed within 14 days of the signing of the Armistice.

While the Armistice terms were clear, what was less clear was exactly how they would happen–or if it could, for that matter. By November 1918, Germany was in the grip of a revolution. The revolutionary tensions in Germany and her armed forces meant that negotiations of the arrangements of the submarine surrender in the days after the Armistice were signed were tinged with uncertainty. On 16 November Eric Geddes, First Lord of the Admiralty, reported to the Cabinet on a meeting held between the British commander-in-chief of the Grand Fleet and Rear-Admiral Meurer, a senior German naval officer, which demonstrated these difficulties.

Meurer had sounded a note of caution. He stated that, while he and his superiors were content to carry out the surrender terms, it was possible that the British did not "appreciate the chaotic conditions existing in Germany, which render the execution of the Armistice Terms extremely difficult … action can only be taken with the consent of the Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Council."

A U-boat on Display in London

However, these fears seem to have been misplaced, as Geddes reported that on 15 November the Soldiers’ Council of the German Submarine Flotillas had released a communiqué stating that "the whole of the crews of Submarine Flotillas conscious of the serious position of the Fatherland and after having striven for their Fatherland for 50 months in need and privation will not refuse to the Fatherland the last and hardest service; they will bring all the submarines to the place which they are ordered."

On 18 November, instruction as to how the surrender would take place began to be issued. The German submarines were to gather off the coast of Harwich at the latitude and longitude of 52º05', 2º05'. The flotillas were to be accompanied by transports so that the crews could be ferried back to Germany after their warcraft had been handed over. The submarines would then be led to Harwich by a force of British destroyers and cruisers.

Once at the surrender anchorage, the German crew of each vessel (except for those who had to tend to machinery) were to parade on the forecastle and await the boarding of a British officer, who would take command of the vessel. On the officer’s arrival, the German officer commanding the submarine was to hand over a full crew list, as well as a signed declaration stating that the submarine was in the following condition:

(1) Batteries fully charged up

(2) Full complement of torpedoes on board, launched back clear of torpedo tubes and without warheads

(3) That no explosives of any sort are on board

(4) That the submarine is in running condition, fully blown

(5) That all of the periscopes are in place, and in working and efficient condition

(6) That all sea valves are closed and in efficient condition

(7) That no infernal machines or booby traps of any sort are on board

With these formalities dealt with, the German crews would leave for motor launches which would take them back to their transport (none set foot on British soil), while the German captain would show the British officer around the submarine, "and give him details of his vessel and every facility for taking over."

The surrender began on 20 November 1918, with Admiral Meurer informing the British that 20 submarines would present themselves to be taken over that day. Over the course of November 1918, a total of more than 160 submarines would give themselves up at Harwich. Some were left around the estuary at Harwich to rust, leading to the port being sometimes nicknamed "U-Boat Alley." However, from before the surrender the government had designs on the propaganda use of the vessels. On 19 November 1918, Prime Minister David Lloyd George explained his desire that captured submarines, "should be distributed and shown in the Thames, the Mersey, the Tees, the Tyne and the Clyde."

Source: UK National Archives Blog, 22 November 2018

|

The Kaiser's Daily Telegraph Affair

Kaiser Wilhelm II

|

A notable event in the run-up to the Great War

occurred in 1908. An interview of Kaiser

Wilhelm II published in Britain's

Daily Telegraph on 28 October 1908 polarized the sentiments of the British public

against Germany at a pivotal time when the German

naval build up already had the island nation worried.

This was not the result the Kaiser had in mind. He

intended the interview as yet another olive branch

offering to Britain. He succeeded not only in agitating the British but the governments of Russia, France, and Japan, as well.

Among the Kaiser's talking points:

– The German people, in general, do not care for

the British, but he was a friend

–His alleged role in raising opposition

against the British during the Boer War needed clarification

–The German naval buildup would continue but

was not aimed at the Royal Navy

This 1906 Punch Cartoon Portraying Wilhelm as a Sea-Serpent Is What the Kaiser Was Attempting to Respond to in the Ill-fated Interview

|

Excerpts:

"You English are mad, mad, mad as March hares.

What has come over you that you are so completely given over

to suspicions quite unworthy of a great nation? Falsehood and

prevarication are alien to my nature. My actions ought to speak for themselves, but you listen not to them but to those who misinterpret and distort them. . . I repeat that I am a friend of England, but you make things difficult for me. My

task is not of the easiest. The prevailing sentiment among

large sections of the middle and lower classes of my own

people is not friendly to England. I am, therefore so to speak,

in a minority in my own land.

Again, when the [Boer] struggle was at its height, the German

government was invited by the governments of France and

Russia to join with them in calling upon England to put an

end to the war. The moment had come, they said, not only to

save the Boer Republics but also to humiliate England to the

dust. What was my reply? I said that so far from Germany

joining in any concerted European action to put pressure

upon England and bring about her downfall, Germany would

always keep aloof from politics that could bring her into

complications with a sea power like England..

"But," you will say, "what of the German navy? Surely, that

is a menace to England! Against whom but England are my

squadrons being prepared?" My answer is clear. Germany

is a young and growing empire. She has a worldwide

commerce which is rapidly expanding, and to which the

legitimate ambition of patriotic Germans refuses to assign any bounds.

The affair did not help the Kaiser at all domestically, either. There was a sense of embarrassment and calls for his abdication. Only a single member of the Reichstag publicly defended him in the aftermath. Wilhelm sulked and remained relatively quiet for months afterward.

Source: Over the Top, October 2008

|

|

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications

|

Order Our

WWI Musical CD

Click on Image for Information

|

Shop at

Amazon.com

|

Order the Complete Collection

Over the Top Magazine

Click on Image for Information

|

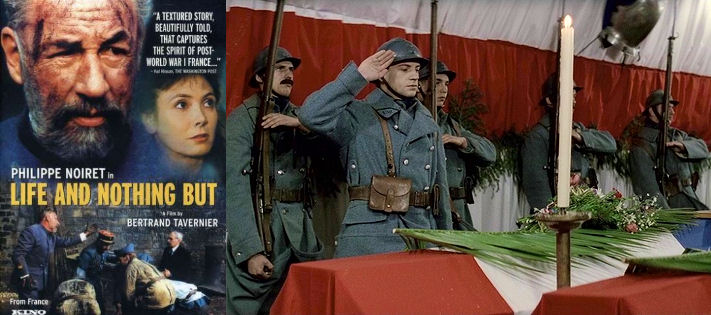

A World War One Film Classic

Set in the vicinity of Verdun during the war's immediate aftermath, Bertrand Tavernier's 1989 Life and Nothing But tells the story of Major Delaplane, a man whose job is to discover the identities of France's unknown dead. He encounters two women looking for their lost men: Irène, a disoriented Parisian aristocrat, and Alice, a former teacher now waitressing so she can be near her lost loved one's battlefield. Philippe Noiret, memorable star of Cinema Paradiso and The Postman, ably reflects postwar France – exhausted and in mourning but still dutiful. Some of the supporting episodes to the main story line are especially moving, the dangerous job of removing bodies from the Tavannes Tunnel disaster, a farmer paying the ultimate price for plowing his field before it's cleared of ordnance, and a spectacular reenactment of a young soldier selecting France's Unknown Soldier at the Verdun Citadel. (Shown above.) Watching Life and Nothing But film will leave you feeling more connected with the experience and heritage of the Great War than with most action-oriented films. It's available on Netflix and for purchase on Amazon.

|

|

Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

(Or send it to a friend)

(Or send it to a friend)

|

Design by Shannon Niel

Content © Michael E. Hanlon

|