April

2020 |

|

|

|

O Canada!

Canadians Over the Top at Amiens by Alfred Bastien

On one of my battlefield tours that was focused on the 1917 battles in Flanders, I took the group to a place called Frezenberg Ridge east of Ypres. I was describing an action involving one of the Scottish divisions when I spotted some Canadian flags and military personnel. Naturally, I stopped the bus to discover what was going on and I found the Canadian Army major who was in charge. I learned that he and his men were there to support the re-dedication of a memorial to their unit, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, for an action in 1915. We had a nice chat and parted. Two days later, we ran into the major and his troops again at Vimy Ridge. At that point, I said something like, "You Canadians get all over the place, don't you." He replied that was exactly the way the Canadians were in World War One, and they always ended up in the middle of things. I decided to dedicate this issue of the Trip-Wire to the small (100,000 men +/- peak-strength), but mighty, Canadian Expeditionary Force that always found the action, and a way to make a difference. They also paid a very high price in doing so, as you will learn here. MH

Canada Enters the War

Training at Valcartier Camp near Quebec City Before Deployment

The fact that Canada was automatically at war when Britain was at war in 1914 was unquestioned as from coast to coast: in a spirit of almost unbelievable unanimity, Canadians pledged support for Britain. Sir Wilfrid Laurier spoke for the majority of Canadians when he proclaimed: "It is our duty to let Great Britain know and to let the friends and foes of Great Britain know that there is in Canada but one mind and one heart and that all Canadians are behind the Mother Country." Prime Minister Robert Borden, calling for a supreme national effort, offered Canadian assistance to Great Britain. Borden orchestrated a massive national effort in support of the mother country, but also demanded that Great Britain recognize Canada’s wartime sacrifices with greater postwar autonomy. The offer was accepted, and immediately orders were given for the mobilization of an expeditionary force.

With a regular army of only 3,110 men and a fledgling navy, Canada was ill prepared to enter a world conflict. Yet, from Halifax to Vancouver, thousands of young Canadians hastened to the recruiting offices. Within a few weeks more than 32,000 men gathered at Valcartier Camp near Quebec City; and within two months the First Contingent, Canadian Expeditionary Force, was on its way to England in the largest convoy ever to cross the Atlantic. Also sailing in this convoy was a contingent from the still separate British self-governing colony of Newfoundland. A suggestion that Newfoundland's men should be incorporated into the Canadian Expeditionary Force had earlier been politely but firmly rejected.

Upon reaching England the Canadians endured a long miserable winter training in the mud and drizzle of Salisbury Plain. In spring 1915, they were deemed ready for the front line and were razor-keen. Nothing, they believed, could be worse than Salisbury. In the years that lay ahead, they were to find out just how tragically wrong that assessment was.

The first Canadian troops to arrive in France were the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, which had been formed at the outbreak of war entirely from ex-British Army regular soldiers. The "Princess Pats" landed in France in December 1914 with the British 27th Division and saw action near St. Eloi and at Polygon Wood in the Ypres Salient. Today, their battalion memorial stands on high ground of just north of Hooge.

Early in February 1915, the 1st Canadian Division reached France and was introduced to trench warfare by veteran British troops. Following this brief training, they took over a section of the line in the Armentières sector in French Flanders. Mention should be made of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, whose Great War experience is forever linked with that of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. In 1914, however, it was a separate Dominion from Canada, and would not become a Canadian province until 1949. Independently, Newfoundland raised and maintained a regiment that over the next four years was kept at battlefield strength through voluntary enlistment. The regiment was integrated with the British army, serving mainly with the 29th British Division at Gallipoli and on the Western Front. Its losses in several battles were greatly felt within the small dominion of 242,000 residents, and keeping the regiment at battle strength was difficult but achieved.

Source: Veterans Affairs of Canada

A Disproportionate Contribution

to Victory

A Year After Arrival: Seasoned Canadian Troops on the March

During the last phase of the Great War, miscounted, but universally remembered as the "100 Days," the cutting edge—the most effective assault units—of the British Army were its Australian and Canadian Corps. The substantial Australian contribution to victory will be dealt with elsewhere, here in this issue of the Trip-Wire we are focusing on Canada. By July 1918, the holding of the line at the first gas attack at Ypres, Vimy Ridge, Hill 70, and the capture of Passchendaele ridge were legendary–all battles that had been impossible to win until the Canadians moved to the front. The Canadian Corps, led post-Vimy by Lt. General Sir Arthur Currie, had proven to be unstoppable. In fact, the enemy had named the Canadians "storm troopers."

After the war British prime minister Lloyd George wrote of the Canadians, “Whenever the Germans found the Canadian Corps coming into the line, they prepared for the worst.” The Canadian Corps' performance during the 100 Days campaign lived up to their reputation. Alongside the Australian Corps, the Canadians spearheaded the Amiens assault of 8 August, forced the Canal du Nord, took Bourlon Wood, Cambrai, and Valenciennes, and—on the last day of the war—found itself in Mons, where the British Army had started its war over four years before.

The "Grit" of the Canadian Soldier on Display at Passchendaele, 1917

From the beginning, the politicians and future generals of the CEF knew they had a major learning curve to follow and that their men needed demanding and repeated exercises before they were ready to deploy. In Europe, they prepared the men for missions like the capture of Vimy Ridge with specific and authentic training exercises before launching an assault.

In the area of leadership, the CEF could not have been luckier than to fall under the command of General Julian Byng, who fostered the best instincts of his Canadians and also spotted the most capable and innovative general of the Canadians, Arthur Currie, and saw to it that Currie succeeded him as leader of the Canadian Corps.

Regarding the undeniable "grit" of the Canadian soldiers, this is a quality that's observable but difficult to analyze. Maybe war correspondent Philip Gibbs had a sense of it when he wrote, “The Canadians fought the Germans with a long, enduring, terrible, skillful patience.”

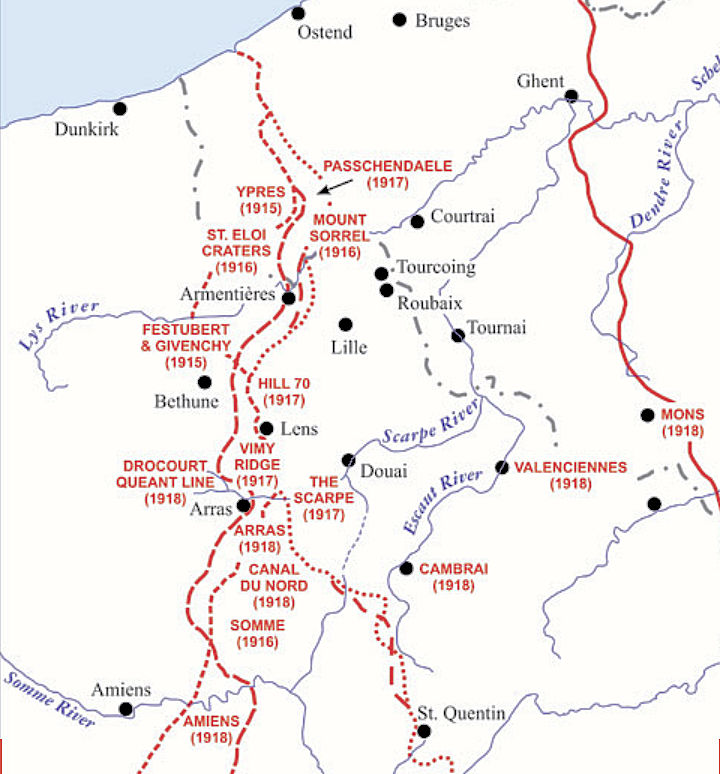

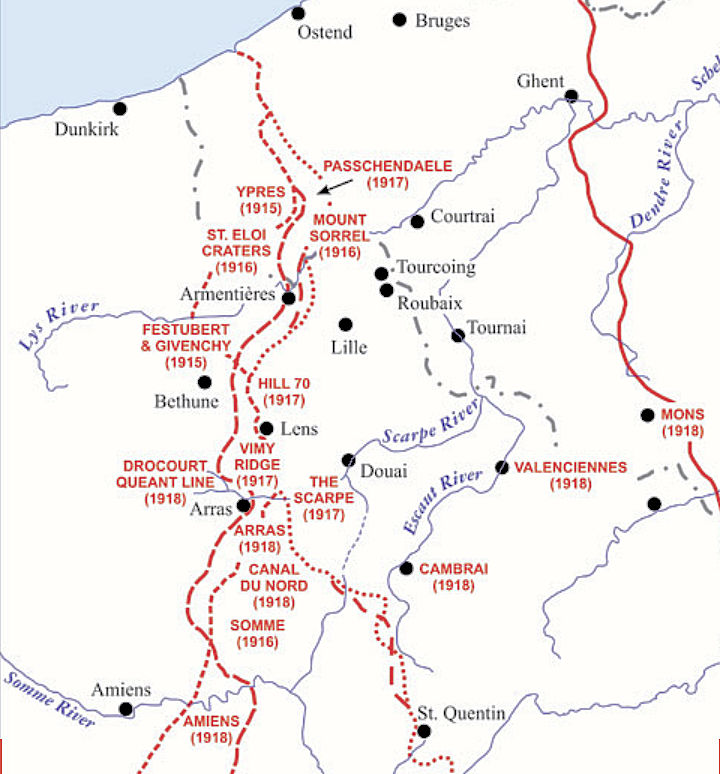

Canadian Operations, 1915-1918

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

|

|

Different Perspectives

There is a plethora of quality material on the Internet about the Canadian effort in the war. Here's a starting list of some of the best sites.

Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War (PDF)

Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War (PDF)

Canadian War Museum: Official First World War Photographs

Canadian War Museum: Official First World War Photographs

Life on the Canadian Home Front (PDF)

Life on the Canadian Home Front (PDF)

The Forgotten Ruthlessness of Canada’s Great War Soldiers

The Forgotten Ruthlessness of Canada’s Great War Soldiers

Underage Soldiers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (PDF)

Underage Soldiers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (PDF)

Canada's Golgotha or the Legend of the Crucified Soldier

Canada's Golgotha or the Legend of the Crucified Soldier

Overlooked Victory: The Attack on Kitchener's Wood

Overlooked Victory: The Attack on Kitchener's Wood

Sir Sam Hughes

Sir Sam Hughes

Yanks in the CEF (There was a bunch.)

Yanks in the CEF (There was a bunch.)

How the First World War Changed Canada

How the First World War Changed Canada

After Vimy Ridge

We went up [Vimy] ridge as Albertans and Nova Scotians, we came down as Canadians.

Unidentified CEF Veteran

Canadian Fact Sheet

Wounded Soldier Delivered

There are two astonishing details about the contribution of the Canadian Expeditionary Force in the Great War. The first is Canada's enormous per capita casualty count. From 1915 to 1918, a nation of barely 8,000,000 citizens sent 425,000 men overseas, lost 61,000 killed and 173,000 wounded. The second concerns the sheer number of battles in which Canadian units played a positive and sometimes decisive role. Besides their legendary victory at Vimy Ridge, Canadian forces saved the day at Ypres in 1915 by plugging the gap in the Allied line with their attack from Kitchener Wood, and they played a prominent and effective role in the great turn-around battle at Amiens on 8 August 1918. The list of battles where Canadian forces played a key role includes:

Neuve Chapelle

Second Ypres

Festubert and Givenchy

St. Eloi, Mont Sorrel, Hill 62

Battle of the Somme (Courcelette)

Vimy Ridge

Hill 70

Passchendaele

Amiens

Second Cambrai

Return to Mons

Attacked by Flamethrowers

I don't know of a better, or more terrifying, description of what it was like to be attacked by flamethrowers than that contained in The General Dies in Bed. The novel, written by Canadian veteran Charles Yale Harrison, was published in 1930. Critics at the time considered it the finest of the war's semi-autobiographical antiwar treatments.

They are coming! We look behind us. They have laid down a barrage to cut us off. We are doomed. Anderson jumps from his gun and lies groveling in the bottom of the shallow trench. I tell Renaud to keep firing his rifle from the corner of the bay. Broadbent takes the gun and I stand by feeding him with what ammunition we have left. They are close to us now.

They are hurling hand grenades. Broadbent sweeps his gun but still they come. The field in front is smothered with grey smoke. I hear a long-drawn-out hiss. Ssss-s-sss!

I look to my right from where the sound comes. A stream of flame is shooting into the trench.

Flamenwerfer! Flame-throwers! In the front rank of the attackers a man is carrying a square tank strapped to his back. A jet of flame comes from a nozzle which he holds in his hand. There is an odor of chemicals. Broadbent shrieks in my ear: "Get that bastard with the flame." I take my rifle and start to fire. Broadbent sweeps the gun in the direction of the flame-thrower also. Anderson looks nervously to the rear. "Grenades," I shout to him. He starts to hurl bombs into the ranks of the storm troops.

Odor of burning flesh. It does not smell unpleasant. I hear a shriek to my right but I cannot turn to see who it is. We continue to fire towards the flame-thrower. Broadbent puts a fresh pan on the gun. He pulls the trigger. The gun spurts flame. He sprays the flame-thrower. A bullet strikes the tank on his back. There is a hissing explosion. The man disappears in a cloud of flame and smoke.

To my right the shrieking becomes louder. It is Renaud. He has been hit by the flame-thrower. Flame sputters on his clothing. Out of one of his eyes tongues of blue flame flicker. His shrieks are unbearable. He throws himself into the bottom of the trench and rolls around trying to extinguish the fire. As I look at him his clothing bursts into a sheet of flame. Out of the hissing ball of fire we still hear him screaming. Broadbent looks at me and then draws his revolver and fires three shots into the flaming head of the recruit. The advance is held up for a while. The attackers are lying down taking advantage of whatever cover they can find. They are firing at us with machine guns.

Doughboys in the Meuse-Argonne

Detail, Lost Battalion Memorial

Charlevaux Mill, France

From: Lost Battalion Tours / Rob Laplander & Mike Cunha, Tour Leaders

When: 8-15 August 2020

Details: Download Flyer

HERE.

For reasons well-known to our readers, all the World War One organizations have

canceled their near-term events and are holding off announcing anything new. We will include news on any events that are scheduled for 2020 as soon as we hear about them.

|

|

Forgotten Victory: Hill 70, August 1917

Canadian Trench Closest to Hill 70

From The Canadian Encyclopedia Article by Brereton Greenhous and Jon Tattrie

The capture of Hill 70 in France was an important Canadian victory during the First World War, and the first major action fought by the Canadian Corps under a Canadian commander. The battle, in August 1917, gave the Allied forces a crucial strategic position overlooking the occupied city of Lens.

Lieutenant General Arthur Currie took command of the Canadian Corps (see Canadian Expeditionary Force) in June 1917, following the Corps' victory at Vimy Ridge. Replacing British General Julian Byng, Currie was the first Canadian put in charge of the Corps, Canada's main fighting force on the Western Front.

German Strongpoint Defending Hill 70

In July, Currie received orders from Douglas Haig, commander-in-chief of all British-led forces in western Europe, to capture the French coal-mining city of Lens. Haig hoped this action would divert German attention and military resources away from the major Allied offensive then raging at Passchendaele, in Belgium.

Lens, which lay inside German-occupied territory not far from Vimy Ridge, had suffered terribly in the war. The Canadians were sent to capture a city that lay half in ruins. Currie thought that Hill 70 — an elevation on the outskirts of Lens, so named because it was 70 meters above sea level — was tactically more important. He believed that a traditional, frontal assault on Lens, followed by an Allied occupation of the city, would be futile if the Germans could simply shoot down at the Canadians from the commanding hills. So Currie convinced his superiors, including Haig, to drastically alter the plan of attack, by making Hill 70 the Canadians' main objective.

Canadians Occupying a Trench on Hill 70

Currie believed that by capturing the hill he could aggravate the Germans in surrounding positions and provoke them to come out of their dugouts and attack. The Canadians could then kill large numbers of the enemy and drive them out of the area.

Throughout late July and early August, as the Canadians prepared to assault Hill 70, they harassed and distracted the German forces.

Hill 70 was a treeless elevation that dominated Lens. The city itself had been bashed by years of warfare, and German trenches cut through the ruins of the brick homes of the city's coal miners. The ruins offered plenty of cover for the Germans in the city.

The Canadians eventually captured the heights of Hill 70, but the cost was high. By the end of only the first day, 1,056 Canadians were dead, 2,432 were wounded and 39 had been taken prisoner. It's not known how many Germans died that day.

Memorial at Hill 70 Under Construction (Opened 2017)

Fighting continued around Hill 70 through 18 August, with the Canadian Corps withstanding continued German resistance and counterattacks, in localized fighting that included mustard gas and flamethrowers. After four days of hard combat, the Canadians turned back 21 German counter attacks and held on to their new positions atop Hill 70. About 9,000 Canadians were killed or wounded in the overall battle, while an estimated 25,000 Germans were killed or wounded.

The fighting at Hill 70, overshadowed by the more famous Canadian battles at Vimy Ridge in April 1917 and at Passchendaele in the fall of that year, is not as well-known to many students of the war. However, some historians argue that Hill 70 was one of Canada's most significant contributions of the First World War, more important even than Vimy Ridge. A memorial to the Canadians who fought at Hill 70 was finally dedicated

Sappers at Work

Canadian Tunnelling Company R14, St. Eloi

David Bomberg (IWM Collection)

Canada's Leading Commander: General Sir Arthur Currie

A former militia volunteer, Arthur Currie [b. 1875] advanced through ability and force of personality to become the senior Canadian officer of the Great War. After serving with distinction as a brigade and division commander, he was ready for more responsibility. Currie was an advocate of intense planning and preparation before going into battle — "Thorough preparation must lead to success. Neglect nothing." He was considered aloof from his troops and nicknamed "Guts and Gaiters"; however, Currie often visited his troops at the front

Canadian Corps commander Sir Julian Byng let him apply his theories, placing him in charge of the training and preparations for the assault on Vimy Ridge. After that great success, he succeeded Byng in command and subsequently led his troops in the conclusion of the Third Battle of Ypres [Passchendaele] and a string of victories commencing at Amiens in August 1918.

Knighted after his accomplishments at Vimy Ridge, Arthur Currie became Canada's first full general in 1919. He then served as principal and vice chancellor of McGill University until his death in 1933. His wartime honors included: Commander of the Bath, Legion of Honor, Knight Commander of the Order of St. Michael and St. George, Croix de Guerre, Distinguished Service Medal (USA).

Personally Supervising a Rehearsal for the Assault on Vimy Ridge

Notable Quotes

"I am a good enough Canadian to believe, if my experience justifies me in believing, that Canadians are best served by Canadians."

"We have shown that even in trench warfare it is possible to mystify and mislead the enemy."

"Thorough preparation must lead to success. Neglect nothing."

Address to Canadian Corps, March 1918:

"To those who fall I say: You will not die but step into immortality. Your mothers will not lament your fate but will be proud to have borne such sons. Your names will be revered forever and ever by your grateful country, and God will take you unto Himself."

Source: Roads to the Great War, 10 July 2014

|

100 Years Ago:

The Ruhr Crisis of 1920

Red Revolutionaries in Dortmund

A crisis in Germany came to a head 100 years ago that challenged both the enforceability of the newly implemented terms of the Versailles Treaty and the credibility of the Weimar Republic. It was triggered by an attempted right wing coup in Berlin on 13 March 1920 which aimed to replace the Weimar Republic. It failed, but Communist elements in the industrial Ruhr area seized on the instability to call for a general strike, as a preliminary to mounting their own revolution against the government. Within a week a Red Ruhr Army had been activated, took the initiative, and, after capturing several hundred paramilitary Freikorps troops, occupied the city of Dortmund.

The Weimar government had to respond, and on 2 April 1920 Germany sent troops into the Ruhr valley to confront the Reds. This was in violation of the Treaty of Versailles. Wilhelm von Mayer, Germany's chargé d'affaires to France, met with Prime Minister Alexandre Millerand and said that some German troops had entered the demilitarized neutral zone (the 50 kilometers [31 mi] west of the Rhine River) on Thursday evening but requested a waiver of the treaty in order to confront the leftist rebels.

German Soldiers and Executed Reds

Premier Millerand informed von Mayer that the German troops would have to be withdrawn and on 4 April announced that he would send troops to occupy the German cities of Frankfurt, Darmstadt, Homburg, and Hanau, located within the neutral zone in the Ruhr Valley. Two days later French Army troops under the command of General Degoutte marched into Frankfurt and Darmstadt and began disarming striking workmen. Meanwhile, Germany's Army, the Reichswehr, marched into Essen, site of the largest concentration of leftist rebels in the Ruhr zone. Their suppression efforts, and those of the Red forces were especially brutal, and included summary executions. By 8 April the German Army had gained control of the entire Ruhr north of the River Ruhr with the remaining leftist forces fleeing to the kinder, gentler French-occupied sector.

In total, about 1,000 of the Red forces died, with roughly half that figure for the German Army and Freikorps. The greatest victim of the crisis, however, was the Weimar Republic, which had shown itself both politically weak and diplomatically impotent due to the hated Versailles Treaty. The Ruhr Crisis was a signal that more emergencies were coming soon.

|

The Lasting Impact of Canada's War Effort

Canadian War Memorial at Ottawa

Canada entered World War I as a colony and came out a nation. . .

Corp. Robert Harvey Hoover, CEF

Canada emerged from the First World War a proud, victorious nation with newfound standing in the world. It also emerged grieving and divided, forever changed by the war’s unprecedented exertions and horrific costs.

The war united most Canadians in a common cause even as the extremity of national effort nearly tore the country apart. Few had expected the long struggle or heavy death toll. A war fought supposedly for liberal freedoms against Prussian militarism had exposed uneasy contradictions, including compulsory military service, broken promises to farmers and organized labor, high inflation, deep social and linguistic divisions, and the suspension of many civil liberties. Some women had received the right to vote, but other Canadians–recent immigrants associated with enemy countries–had seen this right rescinded.

Government had intervened in the lives of Canadians to an unprecedented degree, introducing policies that would eventually mature into a fully-fledged system of social welfare. But it had not prevented wartime profiteering, strikes, or economic disasters, leading many to question the extent to which rich Canadians had sacrificed at all. A massive and unprecedented voluntary effort had supported the troops overseas and loaned Ottawa the money it needed to fight the war. The resulting postwar debt of some $2 billion was owed mostly to other Canadians, a fact which fundamentally altered the nature of the postwar economy.

Politically, the war was also a watershed. Prime Minister Borden’s efforts to win the 1917 election and carry the nation to victory succeeded in the short term but fractured the country along regional, cultural, linguistic, and class lines. English and French relations were never lower, and accusations of French traitors and English militarists were not soon forgotten. Quebec would be a wasteland for federal Conservative politicians for most of the next 40 years. Laurier’s forlorn stand against conscription lost him the election and divided his party but helped ensure the Liberals’ national credibility, with a firm basis in French Canada, for decades to come..

Canadian Graves, Albert-Bapaume Road, Somme

Labor, newly empowered by its important role in supporting the war effort, pushed for more rights, first through negotiations and then through strikes. Farmers seethed over agricultural policies and Ottawa’s broken promise on conscription. In the postwar period, both groups would form powerful new political and regional parties.

The war accelerated the transformation of the British Empire into the British Commonwealth and demonstrated Great Britain’s military and economic reliance on the self-governing dominions. Most of the principal Commonwealth heads of government recognized this and saw clearly in their wartime contributions the route to greater independence and standing within imperial councils.

Canada independently signed the Treaty of Versailles (1919) that formally ended the war and assumed a cautious, non-committal role in the newly established League of Nations. London’s wartime agreement to re-evaluate the constitutional arrangements between Great Britain and its dominions culminated in the Statute of Westminster (1931), which formalized the Dominions’ full control over their own foreign policy. Canada’s determination to do so regardless had already been made evident during the 1922 Chanak Crisis, when Ottawa insisted on a Parliamentary debate before considering possible support to Great Britain in a military confrontation with Turkey.

Despite the social and political challenges of the postwar, most Canadians also emerged from the struggle believing they had done important and difficult things together. Their primary fighting force at the front, the Canadian Corps, had achieved a first-class reputation as one of the most effective formations on the Western Front. Their generals and politicians had played an obvious role in victory, and the country itself enjoyed an international standing that few observers in 1914 could have predicted.

Source: Canadian War Museum

|

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications

|

Order Our

WWI Musical CD

Click on Image for Information

|

Shop at

Amazon.com

|

Order the Complete Collection

Over the Top Magazine

Click on Image for Information

|

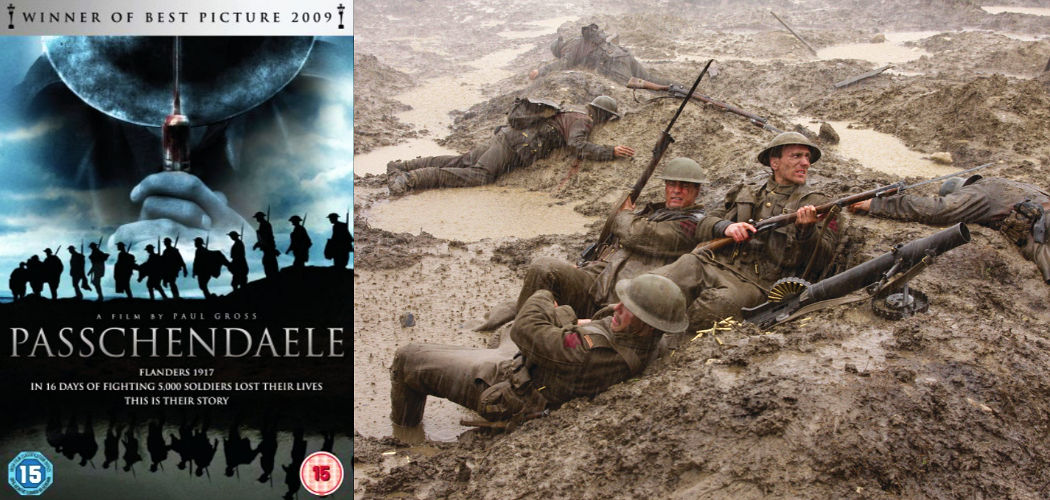

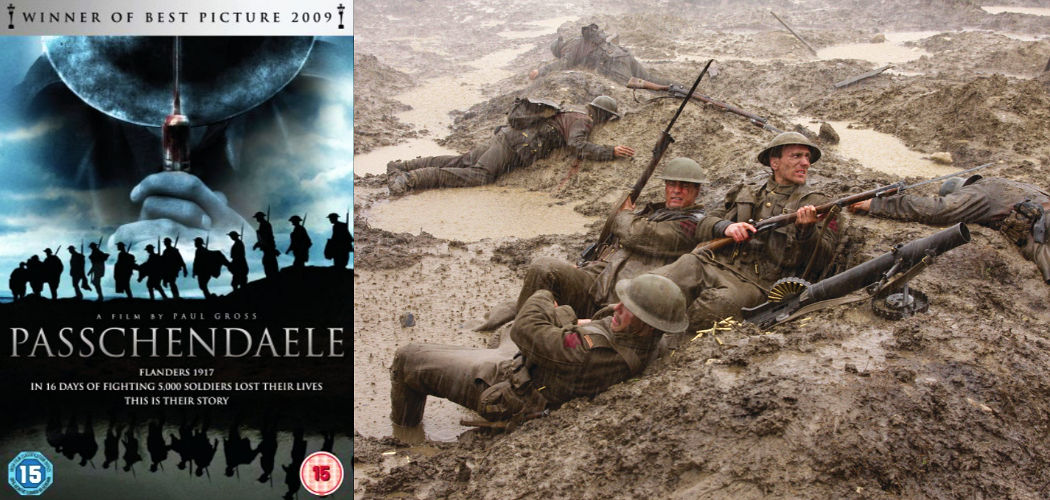

A World War One Film Classic

Passchendaele is one of those war films, like Gallipoli, that spends an awful amount of time on its home front and friendship/love story before getting to the battlefield. The relationships in Passchendaele, however, just aren't as interesting as in the other film. Nonetheless, there are good reasons why the movie won the award of best Canadian film of 2008. Passchendaele does capture and honor Canada's experience in the Great War, particularly the especially unpleasant experience of the Canadian Corps in the battle that gives the film its title.

The central character of the movie, Sergeant Michael Dunne (played by Paul Gross), is sent home with shell shock after the battle of Vimy Ridge. He meets Sarah, falls in love, but also inadvertently encourages her sickly brother David to enlist and join the fight. Despite having escaped further action himself, Michael is guilt-stricken about helping send David off to war. He falsifies an identity and re-enlists. The film takes off when the two soldiers and Sarah, who has signed up as a nurse, all meet up in Flanders. After an hour of this improbable plot and a lot of pedestrian dialog, the last phase of the Battle of Passchendaele unfolds, and it is so well captured (see photo above) it makes the price of admission (or video rental fee) worthwhile. Available through Amazon and Netflix.

|

|

Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

(Or send it to a friend)

(Or send it to a friend)

|

Design by Shannon Niel

Content © Michael E. Hanlon

|