April |

Access |

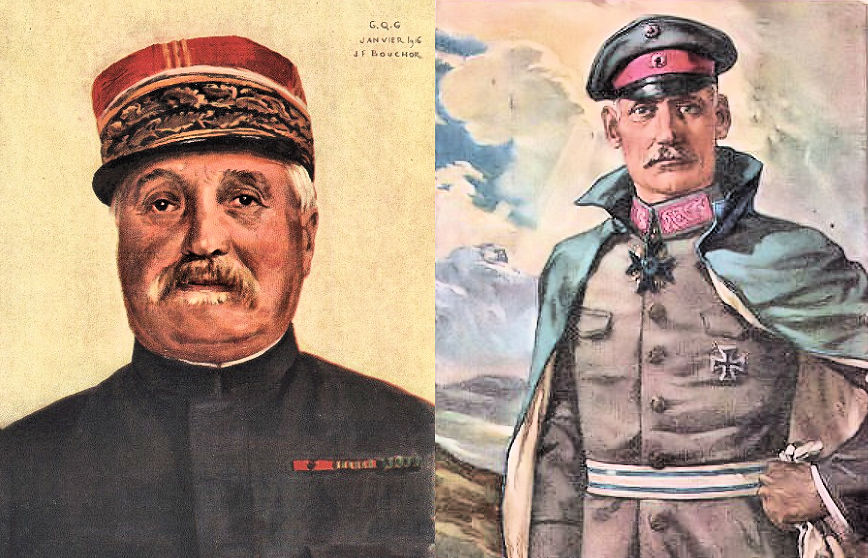

The Lorraine Gap of 1914 Kaiser Wilhelm II Observing Prewar

|

|||||||

Early German Trenches in the Sector |

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

Different Perspectives

Here are some helpful supplemental sources on the early 1914 campaign in eastern France available online.

![]() Prewar Military Planning

Prewar Military Planning

![]() First Shots and First Fatalities

First Shots and First Fatalities

![]() The Great War on the Vosges Front

The Great War on the Vosges Front

![]() The Battle of Mulhouse, 7–10, 14–26 Aug 1914

The Battle of Mulhouse, 7–10, 14–26 Aug 1914

![]() Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria

Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria

![]() U.S. Army Study of the Battle of Morhange-Sarrebourg, 20-23 Aug 1914

U.S. Army Study of the Battle of Morhange-Sarrebourg, 20-23 Aug 1914

![]() Battle of Nancy, 31 Aug–6 Sep 1914

Battle of Nancy, 31 Aug–6 Sep 1914

![]() Two Days in the Rain at the Tranchée de Calonne

Two Days in the Rain at the Tranchée de Calonne

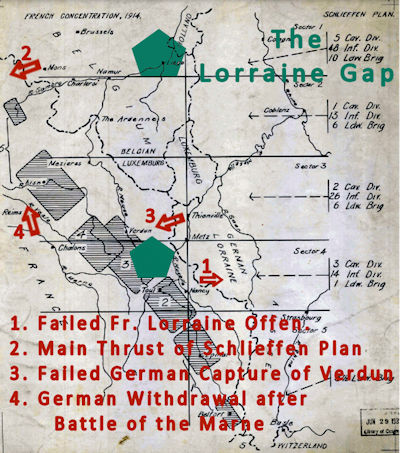

![]() Lorraine Gap Map

Lorraine Gap Map

Click on Link to Open Large Version in New Window

Germany's Vulnerable Point Was Lorraine

Therefore it is obvious that the enemy will attempt to find a vulnerable point, not only of our front but of our country, which can be reached more easily and quickly. Such an opportunity would be offered by invading LORRAINE against the Nineteenth Army. The enemy would be on coveted soil which he wants to liberate, he would threaten one of our most important lines of communication, as well as the SAAR coal and industrial region. Moreover, a sally from the region of VERDUN offers the prospect of paralyzing our utilization of the BRIEY Basin and would likewise endanger one of our most important lines of communication. The two operations combined, enveloping METZ, would drive a wedge into our country which would not only be effective, but which also would seriously influence the conduct of the fighting on the northwest front, in a manner that would prove to be less expensive to the enemy than an attack on that front."

Army Group Commander Max von Gallwitz, 11 Sep 1918

Free Publications |

||

|

Amazon.com |

||

The Zabern Affair

Although by 1914, the retaking of Alsace-Lorraine was not a sufficient casus belli for France, there was one indication that the locals themselves were hoping for liberation just before the war actually broke out. Remembered as the 1913 "Zabern Affair," it started with civil disturbances in the Alsatian garrison town of Zabern. It was caused when, more than four decades after Alsace's occupation by the Germans, an idiot German Second Lieutenant, Günter von Forster, openly insulted the local population at least twice. This led to popular unrest, which was quelled with brutal means.

A broader German-centered political crisis was fuelled by the support given by senior army figures and the German Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg to the behavior of the military in suppressing the protests. On 4 December the German parliament accepted a vote of no confidence in the Chancellor by a huge majority. This unprecedented move remained without effect as, in the German Empire, the Chancellor was appointed by the Emperor and needed his support only. The parliament was ultimately half-hearted in its attempts to increase its power against the executive. Lt. von Forster would be killed on the Eastern Front in August 1915.

Source: Oxford Reference

Tuchman on the Decisive Moment in Lorraine

OHL had convinced itself that a forcing of the Charmes Gap between Toul and Epinal was feasible and would obtain, in Tappen’s words, “encirclement of the enemy armies in grand style and in the event of success, an end to the war.” In consequence, the left wing under Rupprecht was retained in its full strength of twenty-six divisions, about equal to the diminished numbers of the three armies of the right wing. This was not the proportion Schlieffen had in mind when he muttered as he died, “Only make the right wing strong.”

On August 24, having massed 400 guns with additions brought from the arsenal at Metz, Rupprecht launched a series of murderous attacks. The French, now turning all their skills to the defense, had dug themselves in and prepared a variety of improvised and ingenious shelters against shellfire. Rupprecht’s attacks failed to dislodge Foch’s XXth Corps in front of Nancy but farther south succeeded in flinging a salient across the Mortagne, the last river before the gap at Charmes. At once the French saw the opportunity for a flank attack, this time with artillery preparation. Field guns were brought up during the night. On the morning of the 25th Castelnau’s order, “En avant! partout! à fond!” launched his troops on the offensive. The XXth Corps bounded down from the crest of the Grand Couronné and retook three towns and ten miles of territory. On the right Dubail’s Army gained an equal advance in a day of furious combat.

. . . For three days of bloody and relentless combat the battle for the Trouée de Charmes and the Grand Couronné continued, reaching a pitch on August 27. Joffre on that day, surrounded by gloom and dismay elsewhere and hard put to find anything to praise, saluted the “courage and tenacity” of the First and Second Armies who, since the opening battles in Lorraine, had fought for two weeks without respite and with “stubborn and unbreakable confidence in victory.” They fought with every ounce of strength to hold the door closed against the enemy’s battering ram, knowing that if he broke through here the war would be over. They knew nothing of Cannae but they knew Sedan and encirclement.

Barbara Tuchman, The Guns of August

Minding (the Former) Gap

Éparges Spur on the Meuse Heights Would Be

an Epic Battleground for the Entire War

Rupprecht's single action during the post-Marne Second War of Movement influenced the course of the long war to follow, substantially lengthening the butcher's bill for both sides. The Kaiser's troops had seized a substantial enough portion of the Meuse Heights, the town of St. Mihiel and its adjacent fort, Camp du Romans, to eliminate any traffic, river, rail, or road, into Verdun from the south, and their forces had dug in on the south edge of what came to be known as the St. Mihiel Salient, to make their position impregnable - at least for the next four years.

In 1915, the French, now appreciative of the threat presented by the Salient—they came to call it "The Hernia"—made a concerted effort to drive out the defender but failed with heavy losses. Once the basic lines of the Salient were set, intermittent fighting for local advantage took placel almost everywhere along the perimeter with a shift

from fighting on the move to siege-style warfare as

more artillery units arrived on the scene. By January

1915, General Joffre had concluded that the German

occupation of the right side of the Meuse had

effectively neutralized Verdun as a base for future

offensive operations, and he needed to reduce the

general threat it presented to his position in eastern

France. He ordered increased French attacks on the

Meuse Heights initially, but these did not yield

satisfactory results. A new offensive against the

Salient was ordered and then launched at the end of

March.

Peculiarly, this battle does not seem to have—at least

in English language sources—a commonly recognized

name. References can be found to its components, Les

Éparges Spur, the Forest of Apremont, and to the

fighting between Apremont and Pont-à-Mousson,

sometimes called the Battle of the Woëvre, but very

few works address it as a whole.

The new offensive was an all-out assault on both sides

of the Salient in a massive attempt to eliminate it.

There were attacks on the shoulders at Éparges and a

hilly wood just east of Pont-à-Mousson called Bois-le-Prêtre (or Priesterwald by the Germans), near its tip

west of Apremont and down the Tranchée de Calonne,

and attempts to penetrate the rear of the German

front lines launched out of Seicheprey and Flirey on

the middle of the southern face. The Germans were

able to defeat all these efforts in detail through their

superior selection and use of terrain and heavier

application of machine guns and larger artillery.

Concrete German Trenches in the Sector—They Were Planning to Stay

Except for some local successes, the Salient was

unchanged by mid-1915 after some of the worst

fighting ever on the Western Front, while the French

Army found itself, in a quite literal sense, decimated.

The English-speaking world still awaits a first-class

treatment of all the French operations of 1915,

including this tragic battle. Bookstores are full of

volumes about Flanders and Gallipoli in 1915, but little

on Champagne, Artois, or Lorraine.

For the past century, however, the sheer horribleness

of the 1915 campaign has been on display, accessible

to the public in most cases. The battlefields of St.

Mihiel, surprisingly, have remained untouched except

for some minor restoration work and the addition of

appropriate memorials and informational kiosks at places of desperate fighting like Les Éparges, Tranchée de Calonne, Bois d' Ailly, Bois Brûlé, Flirey Village, Bois de Mort Mare, and Bois-le-Prêtre.

After the stupefying losses of 1915, the next two years featured a scaling down, but not the elimination, of the attrition in the sector. Since the capture of the Woëvre and the Heights constricted the supply lines into Verdun, an assault on the city was much more attractive to the German high command, and that battle occupied everyone's attention. In 1917, the Germans were on the defense in the west, and the post-mutiny French Army wanted to fight anywhere but near Verdun.

The former Lorraine Gap, however, would heat up again in 1918 with the arrival of the Yanks, who would refer to the impending battleground as the St. Mihiel Salient.

What the Gap Led to in 1918

American Forces Advancing During the Opening of the

St. Mihiel Offensive

General Pershing had a deep interest in St. Mihiel. He saw the St. Mihiel-Metz corridor as

the royal road into Imperial Germany and had it

assigned as his main operating and training area. In

1918 he started sending a number of his divisions to

the Salient to train. The deployments of the

1st ("First to Fight") and the 26th (New England

National Guard)divisions around Apremont and Seicheprey

were particularly notable. First Division was Pershing's

model unit and many of its officers would transfer

to other AEF units still being formed. By mid-year, with 10,000 American troops arriving

each day, Pershing's force was ready to operate on its

own. His troops, under French command in the Second

Battle of the Marne, were just wrapping up the largest-scale fighting by the United States since the Civil War.

An independent American army was now feasible. The Germans suspected that an attack in the Lorraine

was being prepared but believed that it would not take

place until late in September. In anticipation of this

attack, and to shorten their front line because their

reserves on the Western Front were being depleted,

the German High Command issued orders on 11 September for a gradual withdrawal from the Salient and

the destruction of all things of military value that could

not be moved. However, heavy rain was moving into

the area, so most of the withdrawal was not initiated.

The rain also masked the last-minute movement of the

U.S. troops into attacking positions.

An intense bombardment of the hostile positions

began at 0100 on 12 September and lasted for four

hours. At 0500 the infantry of the main attack on the

south face jumped off. The attack in the forests of the

Meuse Heights was launched three hours later. The

offensive concept for St. Mihiel was that these two

attacks would converge as soon as possible, cutting

off the Salient and trapping most of the German defenders. Thanks to additional artillery furnished by the

French, the First Army had nearly 3,000 guns to support the attack. French and British reinforcements

brought the total number of airplanes up to nearly

1500, which was the greatest concentration of airpower up to that time.

Your Editor at the Lorraine-American Memorial, Flirey, France

As a limited offensive, the St. Mihiel operation would

be a striking success. The First Army took 15,000

prisoners and 257 guns at a cost of about 7,000 casualties. The battle was the largest in the history of the United States to that time. The success was based on the tactical surprise

that was achieved. A major hindrance to Foch's plan for ending the war had been eliminated. However, the operation had not succeeded in bagging

as many of the 65,000 German troops in the Salient as

it might have. The German commanders ordered the

planned-for withdrawal expedited as soon as they

realized a major assault had been launched. Pershing and some of his subordinates like Douglas MacArthur thought the road to Metz was wide open, but other commitments had been made. The attention of the AEF, though, had to focus on its next offensive, to be mounted in a very few days north of Verdun.

While his army was fighting in the Argonne, though,

General Pershing kept up his planning for exploiting

the St. Mihiel Salient. He reorganized his forces and

created the Second U.S. Army to fight on the ground

before Metz. Eventually, Generalissimo Foch was won

over to the concept of exploiting the area of the now-reduced Salient for a major advance, but one much

more broadly based than what Pershing had been

thinking of in September.

Three armies were to attack on 14 November 1918,

First Army and Second Army attacking side by side out

of their respective positions east of the Meuse and the

Woëvre Plain with a new army commanded by General

Charles Mangin on their left flank. The Armistice

precluded this operation, of course. Second Army was

asked to mount some local attacks starting on 9

November to gain some positional advantage had the

Armistice been terminated, but the war ended before

this evolved into a major operation. Thus, the Allies

never fully exploited the strategic opportunity present

in Lorraine during the war.

100 Years Ago:

|

The Spanish Flu vs. COVID-19: the Numbers

The Benefits of Wearing Masks Were Major Controversies

in Both Pandemics

As we approached the first anniversary of COVID and the associated lockdowns, I tried to find an article comparing the magnitude and impact of the Spanish Flu with our current pandemic. After weeks of searching without finding anything useful, I decided to prepare my own article, focusing on the statistics only. I'll admit upfront there are big weaknesses in this strictly statistical approach. The numbers from 1918 (cases, rates of infection, and deaths) have been argued over for a century and there's not really a consensus, just a range of possibilities. The contemporary statistics for COVID have been gathered more systematically and in realtime, but bring along their own uncertainties, false-positive test results, over attributions on death certificates, missed diagnoses, and so forth. Nonetheless, I decided to publish this article, I guess, just because no one else has done this.

What I have tried to show here are comparative statistics for the two pandemics. I've drawn heavily on material from Stanford University, the Worldodometers website, and an excellent article from Wired.com. From these sources, I've compiled the total deaths from both diseases for both the world and the United States. Then I computed the percentage of infections and deaths for the various populations and also the Case Fatality Rate (CFR), the proportion of known infections that result in death—a measure of the lethality of a disease. To better compare the impact of the Spanish Flu vs. COVID, I have also extrapolated the figures for 1918 to the 2020 populations of the world and the United States. Below the figures, I have some caveats and questions about these numbers. MH

Spanish Influenza

World

1918

Population: 1.8 Billion

Infected: Estimated 500 Million (28%)

Deaths: total, as percentage of 1918 world population, CFR

1918 Lowest Est:

17.4 M, .96% 3.4%

1918 Most cited Est:

50 M, 2.8% 10%

1918 Extreme Est:

100 M, 5.6% 20%

Extrapolated death totals for 2021 world population

1918 Using Lowest Est:

75.4 M

1918 Using Most cited Est:

216 M

1918 Using Extreme Est:

433 M

USA

1918

Population: 103 M

Infected: 30 M (28%)

Deaths: total, as percentage of 1918 US population, CFR

Deaths: 675K Percentage .58% 2.25%

Extrapolated death totals for 2021 US population

Deaths: 2.2 M

COVID

2021

Population: 7.8 Billion

Infected: 127 M (1.6%)

Deaths: total, as percentage of 2021 world population, CFR

2.7 M .035% 2.1%

USA

2021

Population: 331 M

Infected: 30 M (9%)

Deaths total and as percentage of 2021 US population, CFR

550 K .14% 1.8%

Comments: As you can see, I'm no professional statistician. However, my look at these numbers suggests that COVID-19 has been nowhere near as serious a health threat as the Spanish Flu based on the percentage of infections, deaths, or CFR. However, I don't think this is in anyway conclusive. Our health care system is much more sophisticated than in 1918 and this should have helped suppress the spread of COVID. Also, many believe the limitations on travel, group assembly, and mask-wearing mandates have been successful limiting factors. (Of course, there is also more research being released on the negative effects of the lockdowns.) How significant is the apparent different targeting of the influenza for younger people and COVID for the elderly? Most important, COVID has not run its course yet. Anyway, having just received my second vaccination, I'm hopeful like everyone else that this will help arrest the pandemic soon. MH

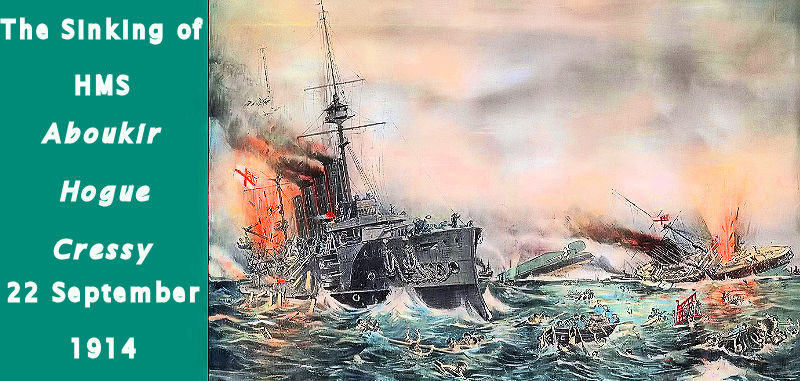

A World War One Documentary

In September 1914, three Royal Navy ships of the obsolete "Armored Cruiser" class were patrolling the English Channel. Under-armed, under-armored, and not very maneuverable, they were sitting ducks or "live bait" in British sailor speak. German U-9's captain saw his opportunity and seized it. In short order, the Aboukir, Hogue, and Cressy, were sent to the bottom. Almost all of the 1,500 seamen aboard the vessels went down with their ships. This fascinating documentary looks at the event from three perspectives: 1) the attack, 2) the shock wave sent through the Royal Navy, when it was made clear how vulnerable their ships were to the enemy's U-boats, and 3) the human tragedy reaching home to the sailor's communities caused by the sudden and massive loss of life.

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon