May |

Access |

We Will Always Have Paris

Opening Session, Paris Peace Conference, 18 January 1919

Since we are focusing on the Paris Peace Conference and Versailles Treaty in this issue, I'll take this opportunity to share what comes to mind for me about those momentous events. Be forewarned, these are not happy thoughts.

"The Inquiry" – Colonel House's Advisory Staff at Paris

America's Siberian Intervention: Part 2 of 4,

|

||||||||

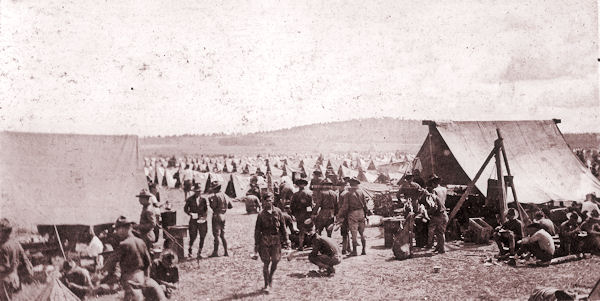

AEF Siberia

|

General Graves arrived at Vladivostok on 3 September 1918 with 5,000 8th Division troops. Finding no threat to the city, he ordered the troops back to their garrison. Graves had hoped to avoid situations like the Ussuri Campaign, and interpreted from the Aide Memoire that U.S. troops were "not here to fight Russia or any group or faction in Russia." A strict policy of neutrality was immediately announced to the troops. Bolsheviks and White Russians would be treated equally. He soon turned his attention to guarding the military stores in Vladivostok and in depots along the Trans-Siberian Railway. He also learned that the most influential Russian commander in the region was the Cossack, Gregori Semenoff. By the time of Graves's arrival in Vladivostok, Semenoff's connections with the Japanese had ripened into a firm but unstated alliance. Nonetheless, Semenoff tried to obtain better artillery pieces and airplanes from the Americans. Graves, who viewed his mission as upholding American neutrality regarding the various factions in Siberia, refused. But he had to acknowledge that Semenoff was a major force to be reckoned with because he controlled the strategic rail link along the Trans-Baikal Railway from Lake Baikal City to Chita.

General Graves Meeting with Semenoff

The first meeting between Graves and Semenoff took place in late September in Vladivostok. Although the tone of the meeting was

civil, Graves claimed that the ataman was not only in the pay of the Japanese but that he could not have lasted a week in Siberia

without the "protection of the Japanese." In October, Graves went to visit the 27th Infantry, which was guarding the major railway

station of Khabarovsk. While there, he met the other main Cossack ataman, Ivan Kalmikoff. The main difference between Kalmikoff and

Semenoff was that the former chose to kill, maim, and rape his victims directly. Semenoff used subordinates to do his dirty work.

The end of World War I in Europe in November 1918 would have a profound effect on conditions in Siberia, but it brought no

immediate change for Graves's AEF Siberia. The Armistice in November 1918 ending the conflict in Europe gave Graves and most

American soldiers in Siberia hopes of returning home. Instead, four American companies settled with the first snows of winter 300

miles south in Spasskoe. While Congress questioned the intervention, Wilson found new excuses for the troops to stay. The

American forces would stay put because President Wilson wanted to wait until after the Paris peace conference before deciding which

of several Russian governments to recognize and whether to withdraw the AEF Siberia from Vladivostok. However, by the time

Graves arrived in Siberia, circumstances had changed. The Czech Legion no longer needed rescuing. The Japanese had 70,000

troops spread all over the region. The search for German and Austria-Hungarian prisoners of war was unnecessary as they willingly

turned themselves in, preferring American rations and humane treatment to freedom. With little else do to, American troops patrolled and guarded the city.

Next Month in Part 3: Winter Comes for AEF Siberia

Sources: Guarding the Railroad, Taming the Cossacks, U.S. National Archives; "AEF Siberia," The Doughboy Center

Reassessing the Paris Peace Conference & the Treaty of Versailles

Meanwhile in Paris, the nucleus of a wild, international, pleasure-crazy crowd, the Big Four were making a desert and calling it peace.

Vera Brittain

![]() "The Paris Peace Conference and its Consequences" by Alan Sharp

"The Paris Peace Conference and its Consequences" by Alan Sharp

![]() "Versailles and Peacemaking" by Dr Ruth Henig

"Versailles and Peacemaking" by Dr Ruth Henig

![]() The Frantic Effort to Finish the Treaty

The Frantic Effort to Finish the Treaty

![]() "An Act of Madness Unparalleled in History" by Jacques Cheminade (PDF)

"An Act of Madness Unparalleled in History" by Jacques Cheminade (PDF)

![]() "The Paris Peace Conference, 1919 – Peace without Victory?" (PDF, Ten Articles Mostly from a British Perspective)

"The Paris Peace Conference, 1919 – Peace without Victory?" (PDF, Ten Articles Mostly from a British Perspective)

![]() Keynes’ Attack on the Versailles Treaty:

(PDF, A Broad Discussion of the Dynamics of the Negotiations)

Keynes’ Attack on the Versailles Treaty:

(PDF, A Broad Discussion of the Dynamics of the Negotiations)

![]() Historian Sally Marks' Response to Keynes et al (PDF)

Historian Sally Marks' Response to Keynes et al (PDF)

![]() Versailles Revisited: After 75 Years

(PDF, Review Essay from 2000)

Versailles Revisited: After 75 Years

(PDF, Review Essay from 2000)

![]() "Warnings From Versailles" by Margaret MacMillan

"Warnings From Versailles" by Margaret MacMillan

![]() "The Strange Case of Versailles" by Martin van Creveld

"The Strange Case of Versailles" by Martin van Creveld

Six from Paris & Versailles

Charles L. Mee, 1981

[T}his meeting signifies for us the end of this terrible war, which threatened to destroy civilization and the world itself. It is a delightful sensation for us to feel that we are meeting at a moment when this terrible menace has ceased to existWoodrow Wilson, Opening Address,

18 January 1919

George Clemenceau, Interview, 9 February 1919

Those insolent Germans made me very angry yesterday. I don't know when I have been more angry. Their conduct showed that the old German is still there. Your Brockdorff-Rantzaus will ruin Germany's chances of reconstruction. But the strange thing is that the Americans and ourselves felt more angry than the French and Italians. I asked old Clemenceau why. He said, "Because we are accustomed to their insolence. We have had to bear it for fifty years. It is new to you and therefore it makes you angry"David Lloyd George, 8 May 1919 (Quoted in Lord Riddell's Diary)

The great day of Versailles has come. The victorious peace will be signed in the Hall of Mirrors on Saturday, June 28. The government wishes the ceremony to have the character and austerity that goes with the memory of the grief and sufferings of our country. Nevertheless, public buildings will be decorated and illuminated. The citizens will surely follow this example.All measures to preserve order have been taken by the government: the public is asked to conform to them for the successful outcome of the ceremony.

The day of Versailles will take place as should such a great day in the world's history.

Mayor of Versailles, Henri Simon,

28 June 1919

Marshal Ferdinand Foch, 1919

Despite my retirement from the business, there will still be possibilities for you to visit the battlefields of the Great War.

AEF Battlefields

Gallipoli

To commemorate the Centennial of the signing of the Treaty of Versailles and to celebrate American philanthropy before and after World War I a Versailles Palace Dinner will be held in the palace's magnificent Hall of Battles on 28 June 2019. Proceeds from the event will be dedicated to building America's National WWI Memorial at Pershing Square. For information email

HERE

2019

From: Valor Tours, Ltd. / Mike Grams, Tour Leader

When: September 2019

Details: Request brochure via Email

HERE.

From: National World War I Museum / Clive Harris & Mike Sheil, Tour Leaders

When: October 2019

Details: Itinerary and Tour FAQ

HERE.

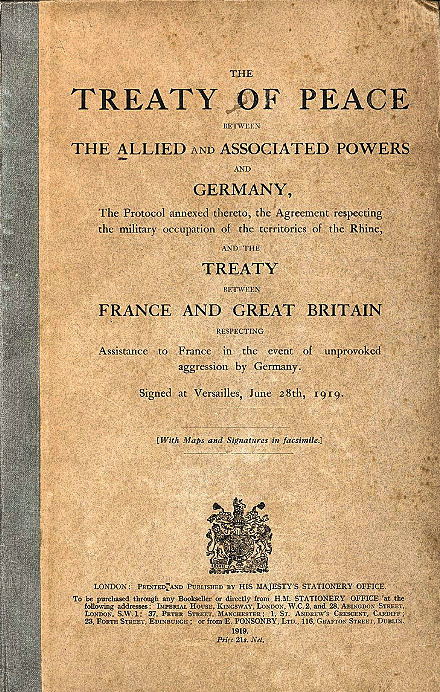

Germany Did Pay Off the Versailles Treaty Reparations.

The Treaty of Versailles originally required Germany to pay 266 gold marks (US $63 Billion). It was rescheduled in 1921 at the Conference of London to 132 gold marks (US $33 Billion). Germany made its final reparations-related payment for the Great War on 3 October 2010, nearly 92 years after the country's defeat by the Allies.

What did you do in the Great War, Mr. Joyce?

I wrote Ulysses. What did you do?

Tom Stoppard, Travesties

Having left his native Dublin in 1904, James Joyce (1882–1941) settled for a decade in picturesque Trieste on the periphery of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He published his masterful short story collection Dubliners on the eve of war. When Italy joined the hostilities in 1915, however, Trieste was threatened with invasion, and the author abhorred the thought of any exposure to war.

He fled to Zurich for the duration, where he was highly productive– completing A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in 1916 and much of Ulysses (published in 1922). In his free time in Zurich, he managed to meet fellow author Stefan Zweig, cross paths with Vladimir Lenin, and observe the birth of Dada, the First World War's contribution to modern art. it was in Zurich, however, where his eye troubles became serious. After the Armistice, Joyce and his family returned to Trieste, but it had become a backwater, no longer an imperial jewel. It was on to Paris, but Zurich held a permanent place in his heart. Fleeing the Nazis, he returned in the Second World War and died there in January 1941

Visit Our Daily Blog

Looking Back: A Retrospective of the War

Part V

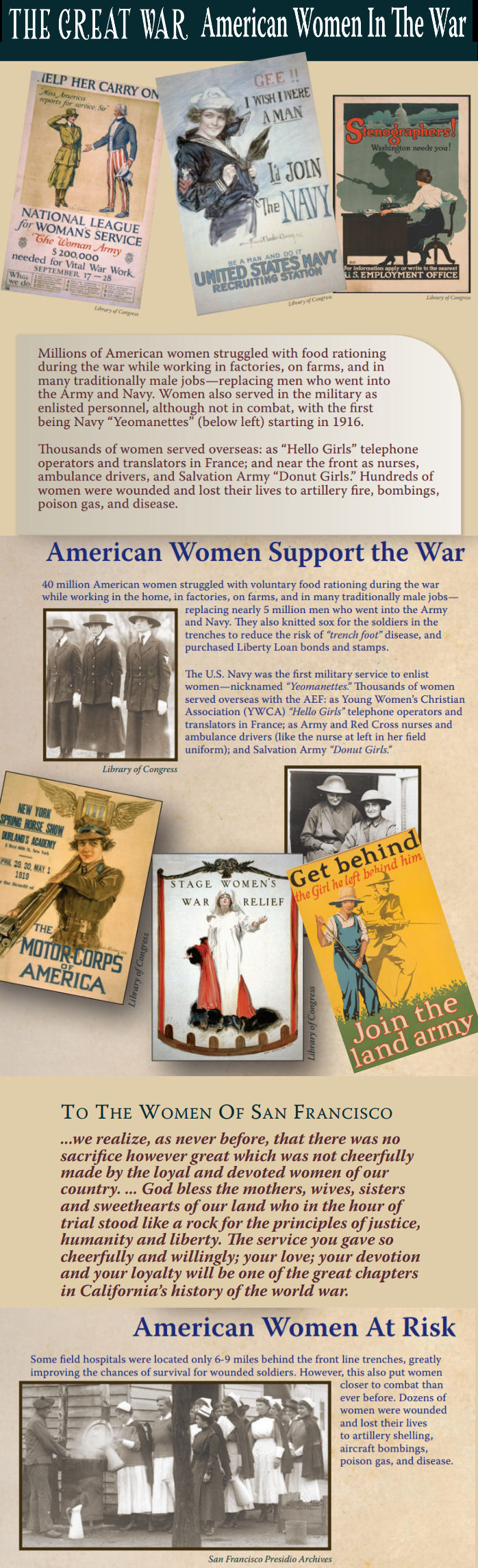

This is our fifth historic banner provided by the San Francisco War Memorial's World War I Armistice Centennial Commemorative Committee. Visit HERE to learn more about the commemorative exhibition being held in the City by the Bay.

The Legend of Hutier Tactics

German Troops Gathering in St. Quentin for Operation Michael

In Hutier Tactics, infiltration attacks began with brief and violent artillery preparation of the enemy front lines in place of the traditional week's long barrage. The new artillery purpose was to suppress enemy positions rather than destroy them. The new artillery preparation would shift to the enemy rear area to disrupt lines of communications, artillery, logistics, and command and control nodes. The goal was disruption at the critical moment. The resulting confusion would degrade the enemy's ability to launch credible counterattacks, concentrate fires, and shift units to fill gaps or block penetrations.

Light infantry led infiltration attacks. They would evade and bypass frontline fortified positions, thus identifying gaps in the front line. The infiltrating light infantry units would "pull" the larger, more heavily equipped, units through. More heavily armed units would follow and attack the bypassed and isolated enemy strong points. Other follow on forces would enter the gaps to reduce the strongpoint and precipitate the collapse of the entire front. These infiltration attacks relied on surprise and speed. Source: Armchair General

Many English-language and French accounts of World War I speak of "Hutier Tactics" as a German secret weapon that nearly won the war in Ludendorff's spring offensive of 1918. When Ludendorff launched his spring offensive on 21 March 1918. . . he achieved surprising success. The German Second, Seventeenth, and Eighteenth Armies broke through the Allied lines on a 100-kilometer front. Especially spectacular was the advance of General Oskar von Hutier's Eighteenth Army, which gained 10 kilometers on the first day, 12 on the second, 8 on the third, and 8 again on the fourth. When this operation came to an end on 4 April, Hutier's army had crushed General Sir Hubert Gough's Fifth British Army, had taken 50,000 prisoners and had come close to driving a wedge between the British and French fronts. Hutier's army had moved forward a total of 38 kilometers, an astounding drive.

The second German attack on 9 April, and the third launched on 27 May, were equally astonishing. For example, on the opening day of the second offensive, German troops advanced 20 kilometers, the longest surge made on the western front since the beginning of trench warfare. The impact of these German successes was tremendous. To many contemporaries, as well as to later historians, it seemed that the recipe for mobile warfare had been found. The victories of the Eighteenth Army were praised not only by the German Emperor, who decorated Hutier with the Pour la merite, but also by the Allies, and especially by the French.

The Paris magazine L'lIlustration in June 1918 called Hutier "Germany's new strategic genius."1 Later that month the New York Times Mid-Week Pictorial presented the portrait of Hutier along with such generals as Ludendorff and Below, with the remark that Hutier was" one of the most successfuI of the German commanders." Several days later the Army and Navy Journal said of Hutier:

General Oskar von Hutier

The enemy has worked out elaborate logistic features in his offensive of the present war which enable him to station his assaulting troops at a great number of points, twenty, thirty and possibly even fifty miles behind the intended point of attack. To General von Hutier in his March offensive. . . is ascribed the successful inauguration of the new method. . . If this method is correctly ascribed to von Hutier's attack, the crushing and sustained effect it produced upon Gough's Fifth Army gives proof of its formidable nature.

Hutier's successes made headlines, and military writers and historians came to·accept him as a genius. Commandant Desmazes of the Military School at Saint-Cyr wrote in 1920: "The battles against the Russians (Sereth and Riga). . . had been the laboratory for a new tactical doctrine fostered by General von Hutier, the Army Commander. . . and by Colonel Bruckmuller, who commanded the army artillery under General von Hutier." Major W. H. Wilbur, who would be a US general officer in World War II, said in his thesis at the Command and General Staff School in 1933: "In the offensive of March 21st, the Germans put into effect a new tactical doctrine. . . (that was) highly successful." Wilbur gave credit for this to Hutier and referred to it as the "new scheme for rupturing the enemy line."

[However] despite widespread emphasis on the Hutier tactics by French, American, and British authors, the German accounts of World War I present no evidence whatsoever of Hutier as the innovator of a tactical doctrine. Ludendorff himself makes no connection in his memoirs between Hutier's Riga campaign and the tactics of 1918. All that Ludendorff says of Riga is: "Supported by higher commands General von Hutier. . . made with his chief of staff, General von Suaberzweig, thorough preparations for the undertaking. The passage was successful. The Russians had evacuated the bridgehead. . . and with few exceptions, offered but slight resistance."

Crossing a Canal During the Third (May) Spring Offensive

General Wilhelm Balck, writing on the development of tactics in the First World War, says nothing of Hutier tactics. Nor does he credit Hutier as an innovator of a specific technique. Nothing is to be found in the German Army's official publication of documents. The same applies to an official publication of lessons of the great war. And in a later official survey, Hutier is treated only as a troop commander. Other German studies are similarly silent. An authoritative and detailed analysis as late as 1938 makes no mention of the Riga operation or of Hutier Tactics or of the influence of eastern front and Caporetto experiences on the Ludendorff offensive A German research historian examined the works of more than thirty German officers who participated in the actions in which the Hutier tactics were employed. . . concluded that "A special Hutier tactics or a so-called Hutier tactic in the presently available German sources [is] nonexistent."

Unfortunately, Hutier's diary was destroyed in World War II, and no document in the German military archives indicates his stand on the matter. It is likely that Hutier, along wit h many other army and corps commanders, contributed to the new tactics. Although it is difficult to credit the individuals involved in these innovations, one thing is certain–Hutier did not invent the tactics. They resulted from an evolutionary process in which many persons participated. If a single individual is more responsible than the others, it is Ludendorff himself, for he made the decision to collect, analyze, and formulate the use of these efficacious ideas.

Ascribing all this to Hutier was the work of the Allied Press, and particularly the French. It is reasonable to assume that the other media carrying the news considered the French Headquarters a reliable source insofar as a contemporary combat report can be reliable. Subsequently, American works would cite principally French sources to support their statements about "Hutier tactics." Combining the press reports with the prestige of the post-World War I French Army, we may reasonably suppose that it was the French who originated and propagated the legend. Why the French made Hutier a hero is a matter of conjecture. . . Perhaps the French had to rely on incomplete and inaccurate information from the front, and therefore made an educated guess as to the origin of the successful German tactics. But to think that the Germans themselves would refuse to credit a hero if one actually existed, is absurd, for they too had to keep up morale. "Hutier tactics" must be relegated to the status of historical legend.

Source: "The Hutier Legend" by Dr. Laszlo M. Alfoldi, Parameters, 1976, No. 2

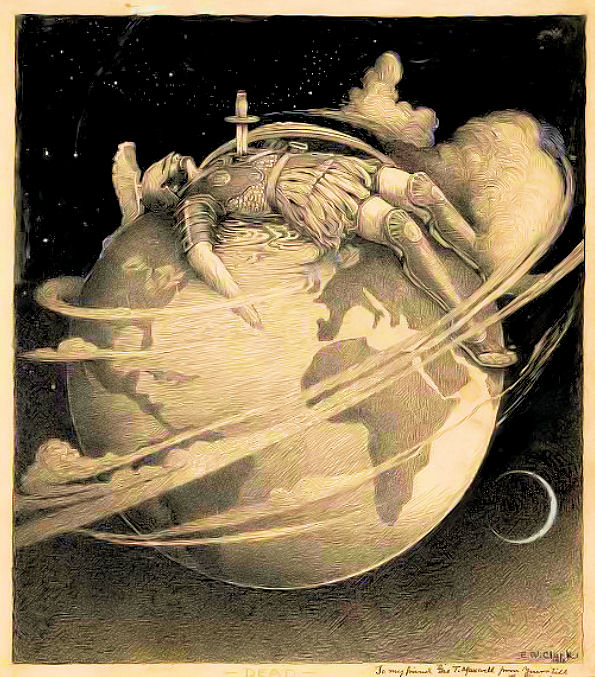

Dead – But the Remains Are Still with Us

Mars, God of War, Vanquished by E.N. Clark, 1918

Remembering Conrad von Hötzendorf

Reviewing the Troops in 1916

Despite Conrad's rather dismal wartime record, after

his death, most Austrians hailed him as a great hero.

The pro-Austrian Christian Social party claimed him as

a great Austrian patriot, while the pro-Anschluss

German Nationalist party emphasized his conclusion

(however reluctant) that Austria's fate should lie in

union with Germany. Meanwhile, the opposition Social

Democrats condemned him as a war criminal. During

and after the war he enjoyed a good reputation in

Germany; Germans placed him on a par with their own

Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff. Eventually,

the Nazis claimed Conrad as a Greater German hero,

holding frequent ceremonies at his Vienna tomb

during the Second World War. Because the defense of

Conrad's reputation after 1918 became bound up with

the defense of the honor of the old Habsburg army, he

remains a controversial figure within Austria down to

the present day.

|

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications |

||

Order Our

|

Shop at |

Order the Complete Collection

|

A World War One Film Classic

A partially disabled veteran of the Great War–he was served in both France's cavalry and air service–director Jean Renoir, provided a multi-layered look at European society caught up in the conflict in 1937's The Grand Illusion. At one level, it's an exciting prisoner of war escape thriller. More broadly, it highlights the class divisions that segregated the armies of each country, yet transcended national boundaries. Its final message, however, is that, despite these differences, there is a shared humanity for all. The major players include two French officers–auto mechanic Lt. Maréchal (Jean Gabin) and aristocratic Captain de Boieldieu (Pierre Fresnay)–who strive to overcome their differences while plotting their escapes from several German prison camps. Meanwhile, de Boieldieu finds a kindred spirit among his captors in a patrician German officer, Rittmeister von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim). The Grand Illusion was the first foreign language film to receive a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Picture. The film is available on Netflix and for purchase on Amazon.

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon