May

2020 |

|

|

|

Why Siberia?

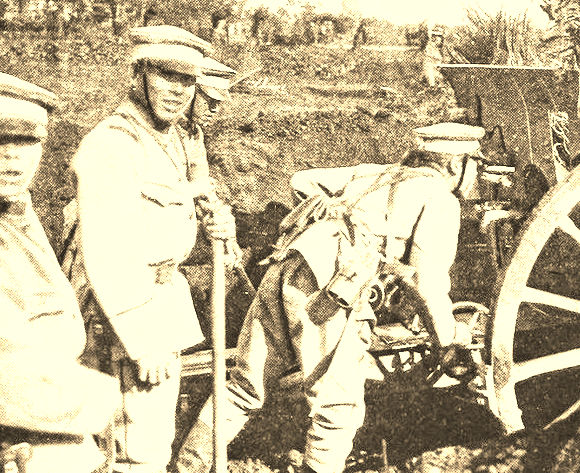

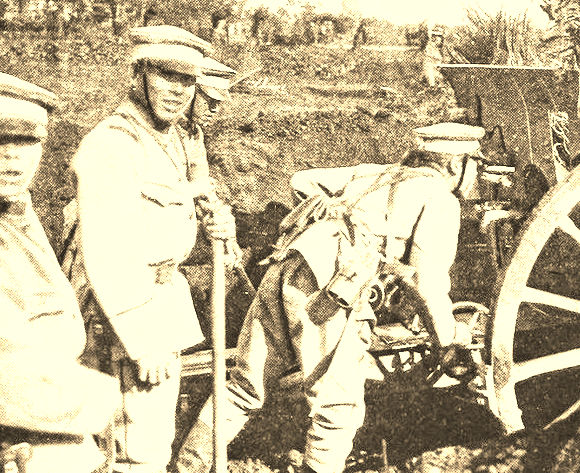

Soldiers of U.S. 27th Infantry Drilling in Siberia

Shoulder Patch AEF Siberia

|

In our next two issues, besides our usual features, we are going to take an in-depth look at one of the most peculiar military excursions of the American republic—the 1918-1920 intervention in Siberia. Professor Christopher McMaster of New Zealand's University of Canterbury will be our guide. Of course, readers will know that, concurrently, the United States also participated in another adventure in Russia, the Allied expedition to northern Russia. I've found, however, that accounts that try to discuss both missions eventually get confusing for the reader (as least for me). Furthermore, as our contributor puts it: "I have concentrated solely on the Siberian Expedition as the two expeditionary forces were separate in command, distance, and in no communication with each other. It is my belief, however, that the reason for dispatching both was similar, although various other factors play a more prominent role in the decision to send troops to north Russia." In this issue, Dr. McMaster concentrates on the politics and diplomacy of President Wilson's decision to intervene. Next month he will cover the multiple dimensions of the military operations and the inevitable decision to extricate the Doughboys from the Siberian briar patch. MH

Woodrow Wilson and the American Expeditionary Force to Siberia

Christopher T. McMaster, PhD

Part 1: Wilson Confronts the New Russia

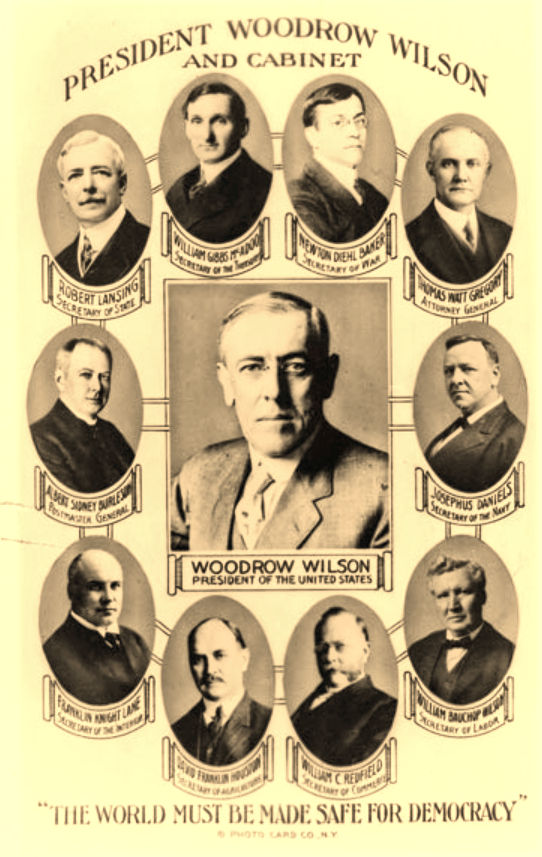

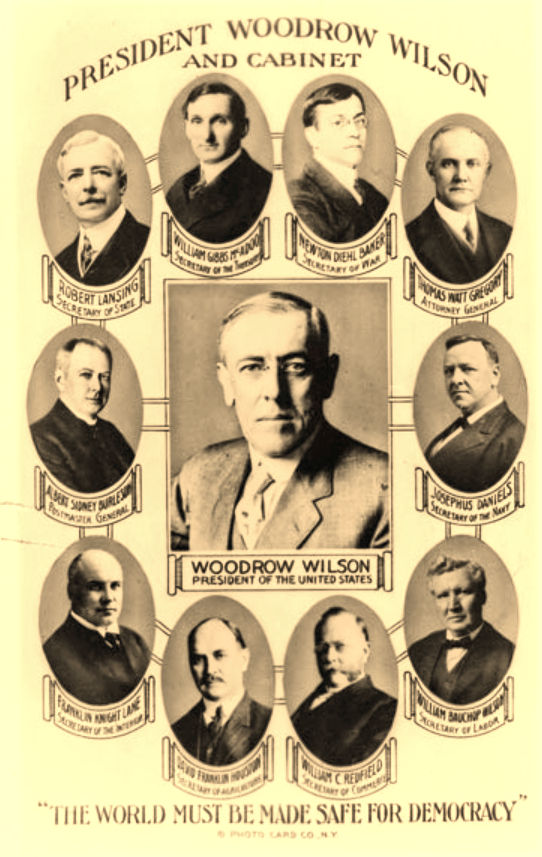

President Wilson and His War Cabinet

On 15 August 1918, American Doughboys landed in Siberia to begin one of the more contentious episodes in U.S.-Soviet relations. The 8,000 thousand troops of the American Expeditionary Force were to remain for more than 18 months, playing a rather forgotten role in the Russian Civil War. Historians have since tried to understand the motives behind President Woodrow Wilson's decision to dispatch U.S. troops to the region. Wilson, as usual, never plainly stated his intentions but cloaked them instead in the eloquent rhetoric that became his hallmark.

Several explanations of Wilson's actions have since emerged. Two interpretations see intervention as part of the Allied war effort, with the president portrayed as believing claims that the Bolsheviks were actually German agents, or as acting in a way to steer his allies into supporting Russian "liberal nationalism" against the threats of both Russian Bolshevism and German militarism. A third interpretation, offered by the former diplomat George Kennan, explains the dispatch of troops ultimately as an effort to rescue the beleaguered "Czech Legion," which had just captured the port of Vladivostok (the future base of operations for Allied intervention) and who were at the time of the U.S. landing eagerly pursuing the Red Guard into the Siberian wilderness.

Perhaps the most pervasive interpretation, however, places the onus for U.S. troops in Siberia onto the emerging empire of Japan. By sending troops to Siberia at a time when Allied intervention appeared inevitable, the president had hoped to restrain Japanese expansion and thereby preserve the "Open Door" in the Far East. The Japanese responded to Wilson's action by sending ten times the number of troops called for by the U.S. president, and proceeded to establish themselves at strategic locations along the Trans-Siberian Railway. The historian John White saw the U.S. military expedition as "a forceful reminder of the American desire" to prevent further Japanese expansion. An expeditionary force that was outnumbered ten to one, vastly out-gunned in artillery, and suffering an 8000-mile supply line stretching across the Pacific Ocean to San Francisco may have appeared more as a reminder of Wilson's difficult position. The fact that American troops worked with the Japanese (despite the mutual and often violent dislike) in achieving a common objective has never been addressed adequately by White, or any other historian researching the 6 July 1918 decision to intervene.

Waiting in Siberia: White Forces

The actual military record of the American Expeditionary Force is extremely useful in understanding Wilson's decision and can be seen as supporting yet another interpretation. To William Appleman Williams the president was decidedly anti-Bolshevik and the primary purpose for intervention was to counter the revolution. "Intervention as a consciously anti-Bolshevik operation was decided upon by American leaders within five weeks of the day Lenin and Trotsky took power". There were no illusions about the threat posed by the Bolsheviks. They were social revolutionaries, as U.S. leaders acknowledged, albeit in private. Their view of socialism and Bolshevism was accordingly accompanied by antagonistic policies, firstly through recognition of counter-revolutionary leaders. Other measures included funding of British and French sponsored campaigns against the Bolsheviks, channeling aid to the White armies forming in Siberia and South Russia, unofficial participation in blockades designed to starve out Communist held regions (and manipulating relief programs to the same end) and clandestinely using the Russian Embassy in Washington's resources to further support counter revolutionary efforts. In the reality of war in Siberia and within the limitations of domestic politics, the AEF was used as another measure in the campaign to topple the government in Moscow. Rather than the culmination of American policy in Russia, the dispatch of the American Expeditionary Force was a natural extension.

Wilson's pragmatic wait-and-see policy allowed him (and his expeditionary force) to exit Siberia when all hope of successful counterrevolution had vanished. Rather than idealistic or misguided, Wilson's Siberian policy allowed the president to cautiously play the situation with a minimum political and military cost.

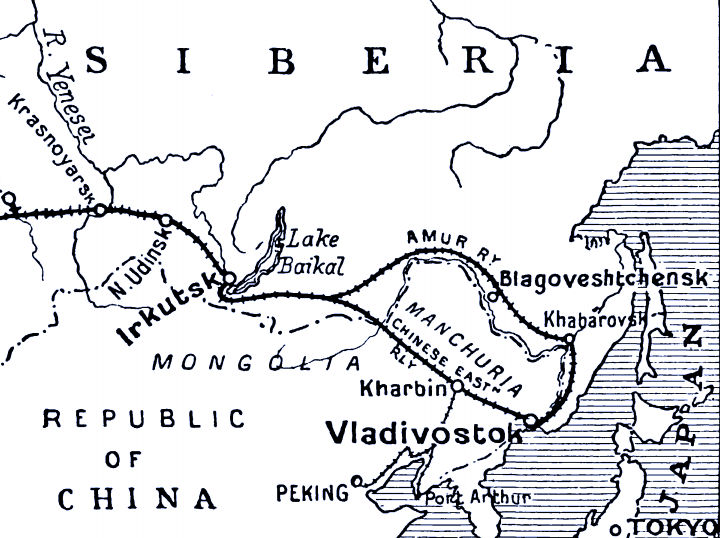

The Port of Vladivostok Would Make an Intervention Feasible

Throughout the winter and spring of 1918 Wilson watched a succession of White leaders emerge to fight the Bolsheviks. The policy of supporting "reputable and sound elements of order" (the chief euphemism for anti-Bolshevik forces) continued in its many forms. The president was extremely cautious, however, in making any definite military commitment. He was not willing to back any horse until there was definite winner. That such a sure thing never arose during the entire period of intervention was a feature of the civil war that Wilson was to adapt to. It is clear that the President had good reasons for his caution and worked within numerous constraints. The war in Europe took precedent in any military planning. Any "line of action through Russia" against Germany was, furthermore, discounted by the Army War College. The issue, the College concluded, "will be settled on the Western Front".

Domestically, Wilson had his priorities. Always with an eye on the postwar settlement in Europe, he could not afford to alienate the Republican controlled Congress with a dubious Russian policy. It was the Republicans, after all, who had the final say over his plans for a "new world order" represented by a League of Nations. The president had to be flexible in policy implementation despite being inflexible and deterministic in policy objectives. Any military option, if required, would therefore have to support counterrevolution whilst simultaneously appearing impartial and not bring a storm of indignation at home. The official reasons for U.S. intervention, as announced in an aide-mémoire of July 17, 1918, would, for a time, fulfill those criteria.

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

|

|

Different Perspectives

This group of links focuses on the build-up and launching of the mission. Next month we will cover the operational aspects of the Siberian intervention.

How Siberia Became Part of Russia

How Siberia Became Part of Russia

Battle for Baikal: The Czech Legion vs. the Red Army (PDF)

Battle for Baikal: The Czech Legion vs. the Red Army (PDF)

Plan of the Entente to Suffocate the Soviet Regime, May–October 1918

Plan of the Entente to Suffocate the Soviet Regime, May–October 1918

Siberian Intervention 1918-1922 (Overview)

Siberian Intervention 1918-1922 (Overview)

Woodrow Wilson’s Ideological War: American Intervention in Russia,

1918-1920

Woodrow Wilson’s Ideological War: American Intervention in Russia,

1918-1920

Lessons from America’s Intervention in Russia

Lessons from America’s Intervention in Russia

Hokushin-ron: Japan's Strategy to Become a Continental Power

Hokushin-ron: Japan's Strategy to Become a Continental Power

The Odyssey of the Czechoslovak Legion

The Odyssey of the Czechoslovak Legion

The Red Victory in Siberia

The Red Victory in Siberia

Leaving Siberia

We left the docks at 6pm. . . It was a satisfying feeling: to watch the lights of Vladivostok slide into darkness and have no regrets in leaving and hope to never have to come again.

Corporal Jesse Anderson, Diary, 9 October 1919

Siberian Timeline

Japanese Troops Were the Earliest

to Arrive

January 1918

First Japanese cruiser arrives in Vladivostok

April 1918

Japanese landing party in Vladivostok

July 1918

President Wilson decides to send American Forces to Siberia

August 1918

U.S. forces receive deployment orders

November 1918

Admiral Kolchak declares himself "Supreme Ruler"

April 1919

Allies reach agreement for guarding railroads

July-August 1919

U.S. Suchan Offensive against Bolsheviks

December 1919

U.S. command notified to prepare for withdrawal

February 1920

Admiral Kolchak executed by Bolsheviks

April 1920

Last American troops leave Vladivostok

April 1922

Japan announces withdrawal of all troops from Vladivostok

Wilson's Biographer Explains the Decision

By Arthur S. Link

During the height of the Second Battle of the Marne, the hard-pressed British and French put heavy pressure upon Wilson to join the Japanese in opening a second front in Siberia, in order to prevent the transfer of German troops from Russia to the western front. Wilson suspected, rightly, that the Allies wanted the United States and Japan to make war against the Bolshevik regime. Wilson thought that Allied hopes to reestablish the eastern front were futile and foolish. He also believed very deeply that the Russian people had the right to work out their own destiny and to establish any kind of government that they pleased, without any outside influence or pressure whatsoever. Hence, he vetoed all suggestions for a Siberian operation.

Wilson relented slightly under the pressure of events in the summer of 1918. A force of seventy thousand Czechs, former Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war in Russia, had banded together in what was called the Czech Legion and were fighting to escape along a route from Russia proper to the Siberian port of Vladivostok. Wilson, in a memorandum of 17 July 1918, announced that he would send a small force to Vladivostok to guarantee the safe exit of the Czechs; he also invited the Japanese to join him in this limited operation. In the same memorandum, Wilson reiterated his intention to oppose all efforts to interfere in Russian internal affairs.

Wilson was motivated in large part by the suspicion, which turned out to be well grounded, that the Japanese had designs on Siberia. Thus, Wilson, while he sent only seven thousand men to Vladivostok, did his best to keep the Japanese contingent to the same size. However, the Japanese government eventually sent in seventy thousand men and seized northern Manchuria and eastern Siberia. Wilson, in August 1918, also sent four battalions from Pershing's force to Murmansk and Archangel in northern Russia to cooperate with British and Czech forces there to safeguard large munitions supplies against capture by the Germans.

Source: Presidential Profiles, World Biography: U.S. Presidents

Doughboys in the Meuse-Argonne

Detail, Lost Battalion Memorial

Charlevaux Mill, France

From: Lost Battalion Tours / Rob Laplander & Mike Cunha, Tour Leaders

When: 8-15 August 2020

Details: Download Flyer

HERE.

For reasons well-known to our readers, all the World War One organizations have

canceled their near-term events and are holding off announcing anything new. We will include news on any events that are scheduled for 2020 as soon as we hear about them.

|

|

Part 2: The Czech Legion

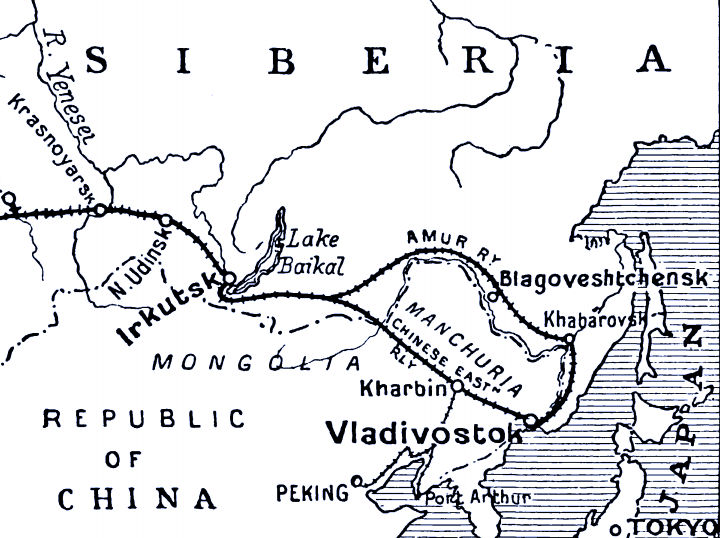

The Czech Legion Secures Vladivostok

The so-called "Czech Legion" ultimately provided Wilson with the justification for intervention. During the early months of the First World War an army of Czechs and Slovaks was formed to fight alongside the Russians against the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Despite sanctioning its formation, Tsar Nicholas II deeply distrusted the Legion and refused to allow it to fight with his troops. The Bolsheviks, after their seizure of power, also uncomfortably viewed the Legion as a foreign army on their soil. Indeed, the Czechs were one of the only disciplined and cohesive fighting forces in Russia at the time, numbering almost 70,000. Finding themselves after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which ended the war between Russia and Germany, as an army without a war, agreements were reached between the Czechs and Bolsheviks whereby the Legion could exit Russia via the Trans-Siberian Railway. The Legion would embark at Vladivostok for France to continue the fight for national independence.

None were to complete the trip during the war. In May at the town of Chelyabinsk the agreement broke down. What began as a clash between Czech echelons moving east and Austro-Hungarian prisoners-of-war being repatriated under the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk moving west resulted in open warfare between the Bolsheviks and the Czechs. The Bolsheviks demanded the Czechs surrender their weapons for passage out of Russia. The Czechs quite naturally refused, and the conflict quickly spread the length of the 5000-mile long railway, over which detachments of the Legion were strewn. After receiving news of the uprising President Wilson informed his allies that he was rethinking the situation.

Armored Train of the Czech Legion

During early June news came that the Czechs had captured Vladivostok and the president made up his mind. With Vladivostok under 'friendly' control, the Allies possessed a secure base of operations. As the eastern terminus of the Trans-Siberian Railway, Vladivostok was the key to launching and supplying any military effort. Ahead lay thousands of miles of track, running westward across Manchuria, and north to Khabarovsk, then also turning west into the Siberian hinterland, leading ultimately to Moscow. It was the supply line built by the last tsar to expand his empire, and it was now the lifeline of the counterrevolution struggling to get back to the center. Indeed, it was the jugular vein of Siberia. Any hope of determining the outcome of the civil war in eastern Russia depended upon controlling and keeping open that railway system.

The Czechs, in one sense, were just the type of force Wilson sought to support in Siberia. They were anti-Bolshevik, anti-German, and anti-Japanese. They were the most effective fighting force at the time in Siberia through which to support counterrevolution. Wilson took the opportunity "to help the Czechoslovaks consolidate their forces and get into successful cooperation with their Slavic kinsmen," as the aide-mémoire announced. Left undefined was who exactly their Slavic kin were. The memoir was equally vague in other areas. The AEF was "to steady any efforts at self-government or self-defense in which the Russians themselves may be willing to accept assistance" and also to guard the vast amount of military supplies that had built up in and around Vladivostok during the war, "which may subsequently be needed by Russian forces in the organization of their own self-defense." Which Russians Wilson had in mind was likewise left undefined.

Siberia

Part 3: President Wilson Sends the Army

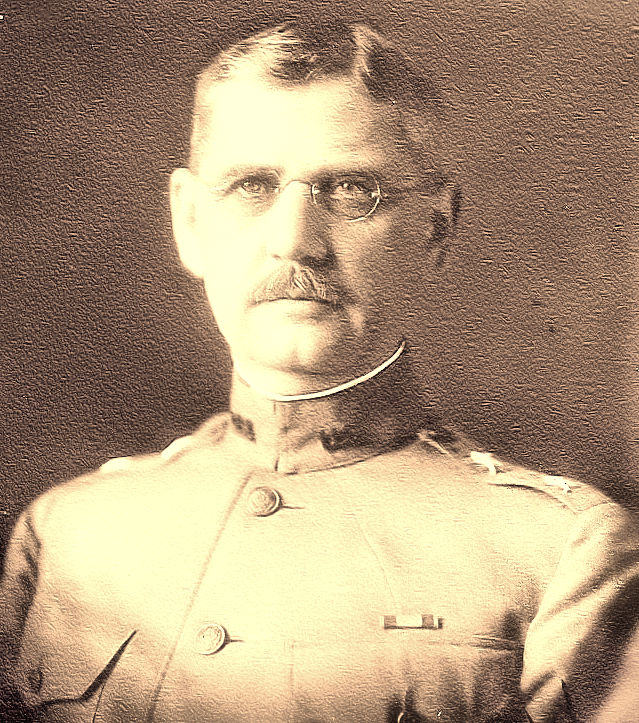

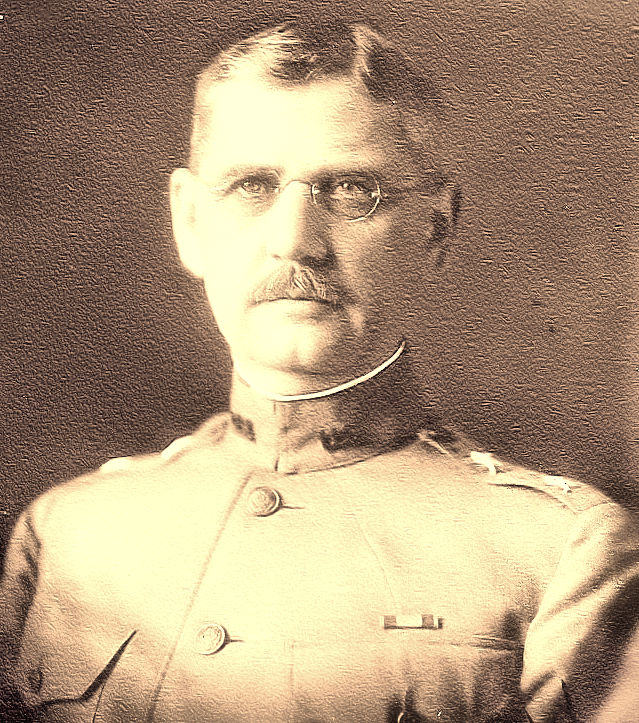

MG William S. Graves, 1918

|

Such a vague example of the president's rhetorical flair was to become the actual orders presented to the man chosen to command the expeditionary force, Major General William Graves. "Watch your step," Secretary of War Newton Baker warned as he handed Graves the pale brown envelope containing the memoir. "You will be walking on eggs loaded with dynamite".

By the time of his arrival in Siberia the general felt he could decipher his instructions fairly well. According to the memoir the AEF was not to become embroiled in the civil war; hence the "non-interference" in Russian internal affairs outlined in the document. Implicit in his orders was aid to the Czechs, which meant, first, maintaining order in Vladivostok. This was achieved in the form of an International Military Police force comprising troops from 12 nations and that preformed its duties in an efficient and disciplined manner.

Second, for the Czechs to consolidate their forces the railway system had to remain operable. Acceptance of this duty immediately compromised any "neutrality" sought by General Graves. The Czech Legion was in revolt against the Bolsheviks and were active partisans in the civil war. To maintain the railway system, moreover, was not just aid to the Czechs; it would benefit the counterrevolution that depended upon the railway. Graves had little illusion about the role his troops played in Siberia. "As I see this question," he would wire Washington, "we become a party, by guarding the railroad, to the actions of this governmental class".

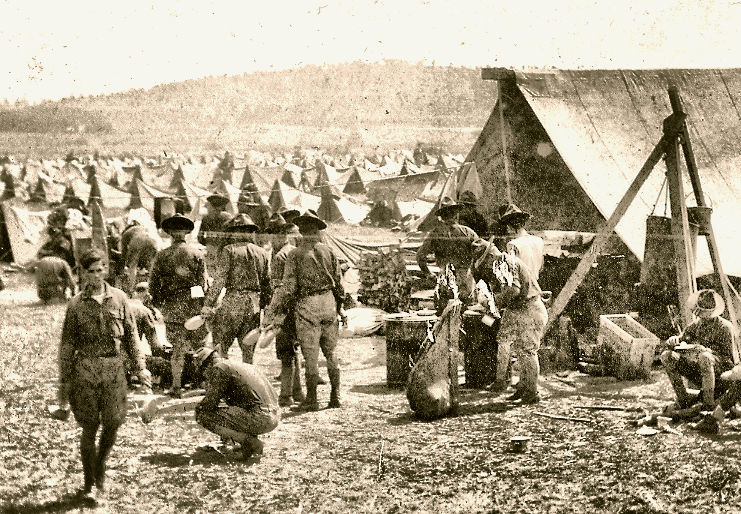

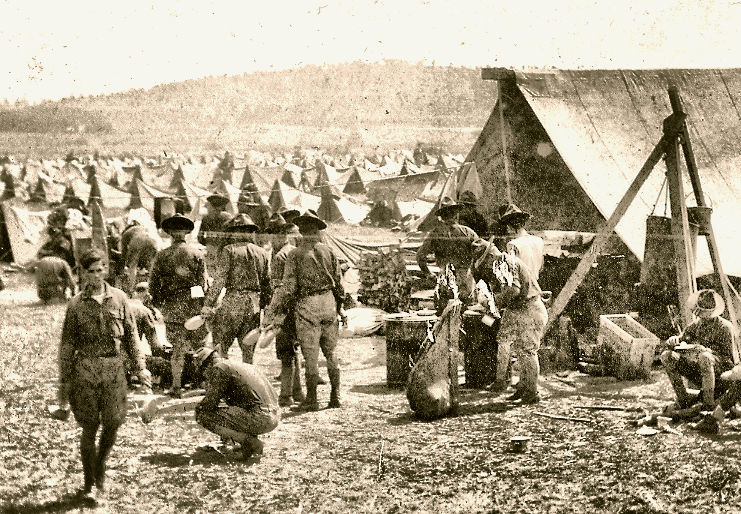

Siberian Assembly Camp for the U.S. 27th Infantry Regiment

His interpretation of Wilson's memoir was to gain the animosity of his allies, who called for more direct action, the violent response from Red Partisans, and numerous calls for his replacement in favor of a more forceful American commander. If, however, Graves were a more impulsive leader, Chief of Staff Payton C. March later wrote, "we would have had to send 100,000 men to get them out alive". Graves was instructed by March 1919 during the intervention to continue his policy until changed by the president. This the president, who could ill afford 100,000 men, never did.

Next month we continue with Dr. McMaster's analysis of President Wilson's decision to join in the Siberian Intervention.

|

100 Years Ago:

Kiev and the Fate of Ukraine in Play

Polish-Ukrainian Forces Parade in Kiev, 9 May 1920

After Germany's collapse, a national uprising broke out in Ukraine in November 1918. The National Directory, which took over Ukraine after a victorious uprising immediately

understood the danger of the Bolshevik Revolution to its independence. War broke out when Lenin sent Red forces into Ukraine and southern Russia. Left alone as the Russian Civil War intensified on other fronts toward the end of 1919, the Nationalists sought an alliance with the newly created state of Poland, whose head, Marshal Józef Pilsudski also opposed the Bolsheviks' expansionist aims. Ukraine was also a tantalizing prize; its grain, coal, and industry would drive a Polish economic revival as part of an intended borderland federation; once again Poland would re-govern the vast lands once ruled by their powerful szlachta, or landed gentry.

In April 1920, Poland and Ukraine concluded a treaty in conjunction with a military convention. Pilsudski signed an agreement recognizing the Directory, headed by Semyon Petliura, as the legitimate authority of an independent Ukraine, in exchange for the return of eastern Galicia to Poland. Later conventions provided for combined military operations and the eventual withdrawal of Polish troops. Though operating at cross purposes, they were united in their goal of driving the Russians from Kiev, with their mutual obstacle being the Red Army.

The Red Army Recaptures Kiev, 13 June 1920

Two longstanding considerations drove Pilsudski's Ukrainian policy. First and foremost, no true state of Poland had existed from 1795 to 1918–the year Poland regained its independence at the end of the war. And second, as a consequence of the first issue, no legitimate frontier had separated the Russian-Polish borderlands for 123 years. Pilsudski was compelled to regain the Polish frontier territory lost to earlier partitions and wished to secure his new border with a Polish-dominated federation of states, which included Lithuania, Belarus, and an independent, though truncated, Ukraine. The coveted territory also included thousands of Jewish villages, known as shtetls, within a region that stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea up to a depth of about 300 miles.

Suspecting a prompt Soviet attack on Poland, Pilsudski quickly organized and launched a preemptive strike into Ukraine on 25 April 1920. While pretending to entertain generous terms from the Soviets for settling the frontier dispute, Pilsudski gathered an army of roughly 300,000 soldiers along the eastern front and struck the Ukrainian capital with around 50,000 troops. His success in capturing Kiev was short-lived, though, as the invasion incited feelings of patriotism among Russian communists, liberals, conservatives, and ex-tsarist officers, who were willing to unite behind the Bolsheviks to drive their enemy from lands considered traditionally Russian. In early June, Semyon Budyonny's Red Cavalry penetrated the Polish lines, driving the Poles and Ukrainians from Kiev and eventually back to Polish territory toward Warsaw. The Ukrainian Nationalists resisted the expanding control by the Red Army until November 1921 when they were routed in a final action at Bazar. A new Polish government, without Pilsudski as head of state, abandoned its dream of an eastern buffer federation and the Ukrainian nationists.

The end of the Ukrainian-Soviet war saw the incorporation of most of the territories of Ukraine into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic which, on 30 December 1922, became one of the founding members of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

Sources: Library of Congress, CIA, and Wikipedia

|

Learn About the Centerpiece of America's New World War One Memorial

On 3 April 2020, I was invited to view a webinar on the status of the National World War One Memorial in Washington, DC, which is now under construction. The report included updates from the engineers and construction managers, as well as a report from lead designer Joe Weishaar. Joe did a wonderful job of describing how the final design has evolved. In my view, the final version has come out simpler but more elegant and stroll-inducing than the 2016 initial proposal. I think it will draw more traffic in this configuration. That said, the reputation and public perception of the quality of the new memorial will be based almost entirely on Sabin Howard's 58-foot long bas-relief sculpture, A Soldier's Journey. In a realistic, non-abstract style, that young and old can readily understand, it dynamically tells its story–that of a Doughboy's service in the war, from home to battlefield back home– moving progressively left to right. The more I'm exposed to his design, with its 38 life-sized figures, the more I'm convinced he has come up with an inspiring theme that honors with grandeur the Doughboys and the nation's experience in the war.

To listen to Sabin Howard discuss his work, I highly recommend this 14-minute documentary, which also includes comments by Americans whose relatives served in the war and some of the best period photographs I've seen.

|

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications

|

Order Our

WWI Musical CD

Click on Image for Information

|

Shop at

Amazon.com

|

Order the Complete Collection

Over the Top Magazine

Click on Image for Information

|

A World War One Film Classic

It has been nearly 40 years since the release of Reds, the much-honored 1981 glorification of the Russian Revolution produced, written, directed and starred-in by Warren Beatty. It's rather hard for a proud former Cold Warrior like myself to recommend a film that was produced by people who apparently had neither read Solzhenitsyn's Gulag Archipelago nor grasped the catastrophic costs of the Russian Revolution—20 million deaths in the Soviet Union, 94 million worldwide, according to the authoritative Black Book of Communism. Nonetheless, I think a view of the film (with some major qualifications) might be worth the 3 hours+ investment of your time to view it, even—maybe especially—if you saw it four decades ago.

Beatty plays a left-tilting Harvard-educated journalist from Portland, OR, named John Reed, who found himself in the middle of the Russian Revolution and won fame for a instant-history of that catastrophe, titled Ten Days That Shook the World. His sympathetic treatment earned him the distinction of being the only American buried within the Kremlin walls. For me, the outstanding quality of the movie–and which makes it worth rewatching (despite what I'm writing otherwise)–is Beatty's directing, for which he was deservedly awarded the "Best Director" Academy Award. He shows an impressive feel for the scale of historical epic film-making and the need to coherently tie many elements and points-of-view together neatly. The movie still has a fresh look, like it could have been filmed last week, and his on-location selections of Helsinki for Petrograd and Spain's Sierra Nevadas for the Caucusus, work perfectly as well. The viewer can't help feeling he's watching a grand and important story, artfully presented. When I viewed it recently, I had the sense I was experiencing a complementary interpretation (the winning side's view) of the Russian Revolution to David Lean's Dr. Zhivago.

Director Beatty interweaves four elements to tell his story, which I will describe and comment on separately:

1. The Love Story: Reed's affair and marriage with Louise Bryant (Diane Keaton) is the dominant narrative, permeating the entire movie. It's not a compelling or interesting relationship for me as Louise implausibly morphs from candidacy for the "Most Annoying Girlfriend on Earth" title (first hour) to "Most Devoted and Heroic Lovemate" (third hour).

2. Interminable, Boring and Pompous Radical Intellectual Debates and Arguments: Talk, talk, talk. Fast forward through these scenes. (Better yet, just skip the first hour. It's filled with Louise and Greenwich Village posers.)

3. The Russian Revolution: After that dreadful first hour, Jack and Louise arrive in Russia just in time for the October Revolution. This is the best part of the movie, beautifully filmed, and capturing the intense energy of the moment and collective awareness by the participants and observers that important history was being made.

4. The Witnesses: The main narrative is supplemented with documentary-style, talking-head cut-ins and voiceovers by 32 elderly, mostly left-wing, political and literary "celebrities" who were around at the time of the revolution, some of whom knew Jack or Louise. They are uninhibited and often informative, with on-point anecdotes, bitchy gossip (wow, women have really long memories), and out-of-left-field non sequiturs. I particularly enjoyed a still sex addled Henry Miller, the astute Dame Rebecca West, and Georgie Jessel singing his favorite World War One tunes.

Available by DVD or streaming from Amazon and Netflix.

|

|

Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

(Or send it to a friend)

(Or send it to a friend)

|

Design by Shannon Niel

Content © Michael E. Hanlon

|