June |

Access |

Belgium 1914

|

Different Perspectives

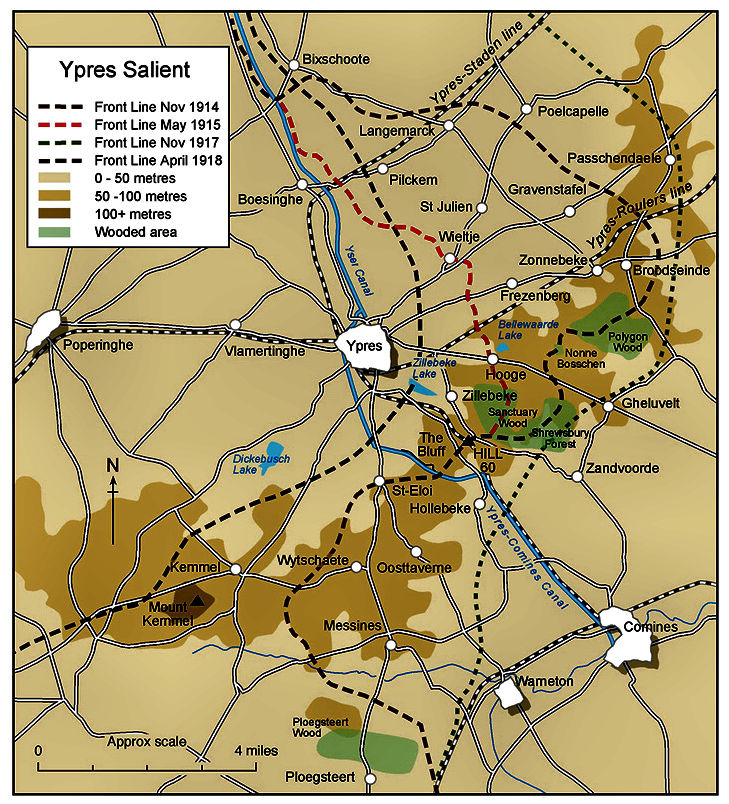

Here are some best maps pertaining to the 1914 campaigns of World War I available online.

Ypres Salient, 1914-1918

|

|||||

Free Publications |

||

|

Amazon.com |

||

Military Casualties During the Antwerp Campaign

Losses to the British forces at Antwerp: 57 dead, 158 wounded, and 936 captured when trying to evacuate the

fortified zone by train. A further 1,500 men would become lost during the retreat and stumble into Dutch territory

where they were interned for the duration of the war.

Losses to the Belgian Army were the following: 9,000 dead, 15,000 wounded, and 40,000 captured as prisoners of

war. A further 33,000 men escaped or were forced into Dutch territory and interned for the duration. Seventy-five

thousand men escaped and retreated toward the Belgian coast.

German losses are difficult to establish since German Army Archives were destroyed during WWII. Great War

period publications were loath to give casualty rates and often inflated or deflated those they did publish. Nor does

the semi-official postwar publication by the German Reichsarchiv in 1925 give any mention of the German Armies own losses other

than being proportionately as high as Belgian casualties when it concerns dead and wounded. The crossing of the

River Nethe line around Lier was the main cause of German losses.

Source: Over the Top, March 2010

The Germans Arrive

Civilians Fleeing Antwerp, October 1914

The last steamer had gone from the Port. The last of the

fleeing inhabitants had departed by the Breda Gate. All that

was left now was the empty city, waiting for the entrance of

the Germans. Empty were the streets. Empty were the boats,

crowded desolately on the Scheldt. Empty were those

hundreds of deserted motor cars, heaped in great weird,

pathetic piles down at the water's edge, as useless as though

they were perambulators because there were no chauffeurs to

drive them. Empty was the air of sound except for the howling

of dogs that ran about in terror, crying miserably for their

owners who had been obliged to desert them. Through the

emptiness of the air, when the dogs were not howling,

resounded only a terrible, ferocious silence, that seemed to call

up mocking memories of the noise the shells had been making

incessantly, ever since two nights ago.

Gendarmes in giant bearskins, chasseurs

in uniforms of green and yellow, carabineers with their shiny

leather hats, grenadiers, infantry of the line, guides, lancers,

sappers and miners with picks and spades, engineers with

pontoon-wagons, machine-guns drawn by dogs, ambulances

with huge Red Cross flags fluttering above them, and cars,

cars, cars, all the dear old familiar American makes among

them, contributed to form a mighty river flowing towards

Antwerp. Malines formerly had a population of fifty thousand

people, and forty-five thousand of these fled when they heard

that the Germans were returning.

Occupation Forces Arriving

The whole city was mine. I seemed to be the only living being

left. I passed hundreds of tall, white, stately houses, all

shattered and locked and silent and deserted. I went through

one wide, deadly street after another. I looked up and down

the great paralyzed quays. I stared through the yellow avenues

of trees. I heard my own footsteps echoing, echoing. The

ghosts of five hundred thousand people floated before my

vision. For weeks, for months, I had seen these five hundred

thousand people laughing and talking in these very streets.

And yesterday, and the day before, I had seen them fleeing for

their lives out of the city-anywhere, anywhere, out of the reach

of the shells and the Germans.

Louise Mack, A Woman's Experiences in the Great War

The Siege of Antwerp: Meanwhile, on to the Yser

Belgian Troops Retreating West of Antwerp

On the morning of 8 October, King Albert issued his evacuation order in response to increasing German pressure. The withdrawal was made in some confusion over the next 48 hours, with the majority of the Royal Marine Brigade withdrawn. The additional British Army force, which meanwhile had landed at Zeebrugge, was placed under the command of Sir John French of the BEF and ordered to cover the Belgian Army retreat and then move from around Gent toward Ypres. The remains of the Belgian field army, dispirited and in some disorder, joined civilian refugees clogging the roads to the coast or made their way into the Netherlands. After more than two months of continuous action against overwhelming odds they were exhausted and needed rebuilding, but they still existed.

One proposal for the Belgian Army was withdrawal west of Calais into France to regroup. Albert saw two great dangers in this. He knew that any attempt to take his army under French command would be resisted by his Dutch-speaking soldiers (who made up most of the lower ranks), and he also saw that if he abandoned Belgian soil he could be usurped as king. It was finally agreed that the Belgian Army would concentrate in the Nieuport-Dixmude area, just inside Belgium, with the French Marines of Admiral Ronarc'h on their right in Dixmude. By 14 October the Belgian Army started to prepare positions along the Yser, and it would be this small strip of Belgium that would be defended by Belgian soldiers, commanded by their own king, until the end of the war.

The Strategically Important Locks at the Nieuport "Goose Foot"

As the Belgian engineers began constructing defenses along the Yser they became aware of French intentions to flood the low ground near Dunkirk, a move which would risk the Belgian forces being trapped by water behind them and by advancing Germans to their front. The obvious solution was to inundate the low-lying farmland running from Dixmude, some nine miles inland, to Nieuport, on the Belgian coast, thus producing a major obstacle to stop the German advance. This low-lying ground was below high tide level and even the canalized rivers flowed between embankments, their water levels higher than the surrounding land.

On the evening of Sunday 25 October, Belgian Army engineers started preparing the area to be flooded. Exhausted soldiers, working with whatever materials were at hand, made the railway embankment watertight. In the small hours of the 28th, the final part of the plan was executed when the Spanish Lock at Nieuport, now under German observation during daylight, was secured in the open position to allow the rising tide to move inland.

The Germans launched eight infantry regiments on a six-mile front on 30 October in an attempt to force the railway embankment before the rising water defeated them. In the little village of Pervyse, Belgian soldiers of the 13th and 10th Infantry Regiments together with a battalion of French Chasseurs repelled the attackers and took 200 prisoners. The Germans succeeded in taking Ramscappelle but, realizing the water behind them was still rising (ankle-deep in the morning, the water was knee-high by midday), started to filter back across the rising flood. The inundation continued to rise while the last few isolated farms still held by the now-marooned enemy were taken.

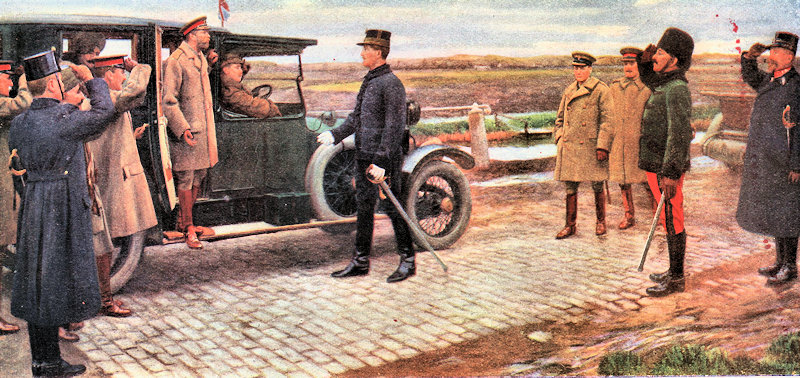

Kings George V and Albert I Meet After the Retreat to the Yser Line

On the morning of the 31st, a Franco-Belgian attack was launched against the Germans in Ramscapelle, but General von Beseler, commanding the German Third Reserve Army Corps, had already ordered a withdrawal across the Yser. This defeat for the Germans, engineered in no small part by two civilians who were familiar with the lock system, was one of the decisive setbacks of the Great War. It was never reversed: the Channel ports supplying the British Army never fell and an immovable anchor was set on the northern end of the emerging Western Front. Farther south on this same day, the fighting west of Ypres was giving the German Army one last opportunity for a breakthrough that could flank and roll up the entire Allied position, but that's another story that will be told in the July issue of the St. Mihiel Trip-Wire.

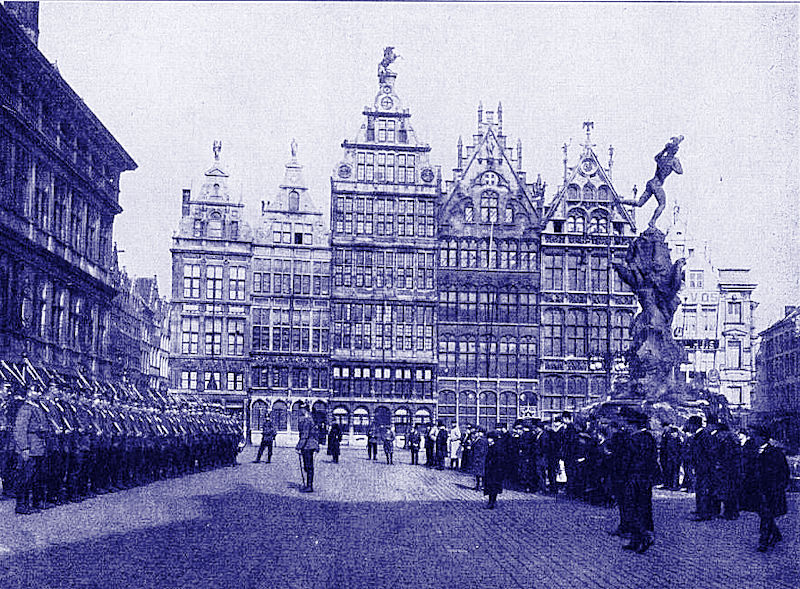

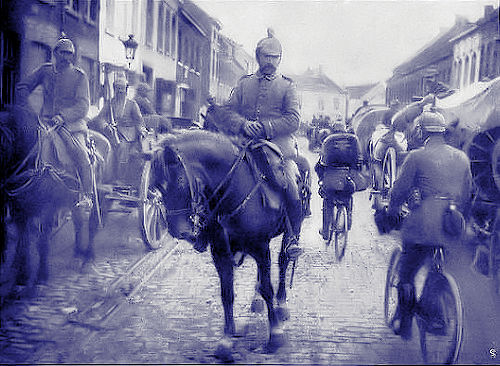

The Siege of Antwerp: Occupation

The first German troops entered the city proper on the

evening of the 10th, by which time the main remnants of

the Belgian field army had regrouped around Gent. The

entry was by and large a calm affair with no resistance

offered anywhere in the city itself. The German media

afterward printed movingly heroic scenes of street

combat in the narrow streets of Antwerp, but these

were (as often the case) simply confabulations, a news

editor's fantasy. Inhabitants of Antwerp who hadn't fled

the bombardment came out to look at the columns and

columns of German and Austrian cyclists, infantry,

cavalry, artillery, naval riflemen, and territorials.

Musters and parades were held in front of the city hall.

The capture of Antwerp was heralded throughout

Germany as a great victory and was celebrated by

the ringing of church bells and displays of captured

Belgian artillery in several cities. German estimates give

106 civilian houses destroyed during the bombardment

of the city with less than 100 civilian deaths, 1300

Belgian artillery pieces taken intact, and food and

military supplies worth several tens of millions of

Reichmarks captured. The German and Central Powers

press made much of the fall of the city, for it was after all one of the largest harbors on the continent, with

extensive shipyards and manufacturing facilities, not to

mention a heavily fortified area. In the end, for the Germans, Antwerp

was not much more than a consolation prize for failing

to take Paris.

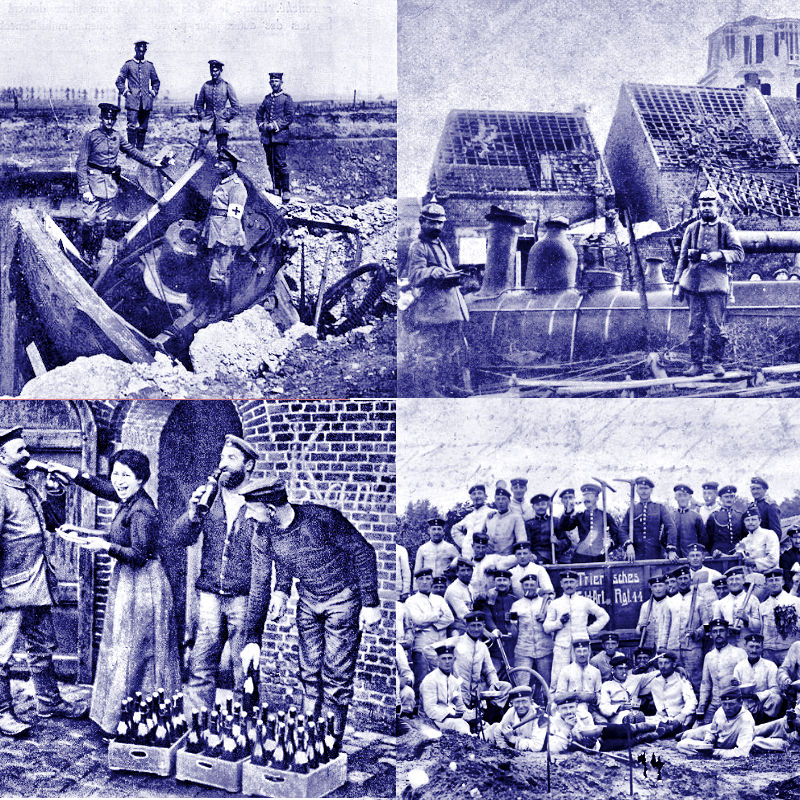

Antwerp's Occupiers at Work and Play

Military traffic downriver was completely closed off by

the neutral Dutch authorities. This was strictly enforced,

with no exceptions made of any kind. Commercial river

traffic and trans-Atlantic emigration were allowed, but

here the British blockade came into play.

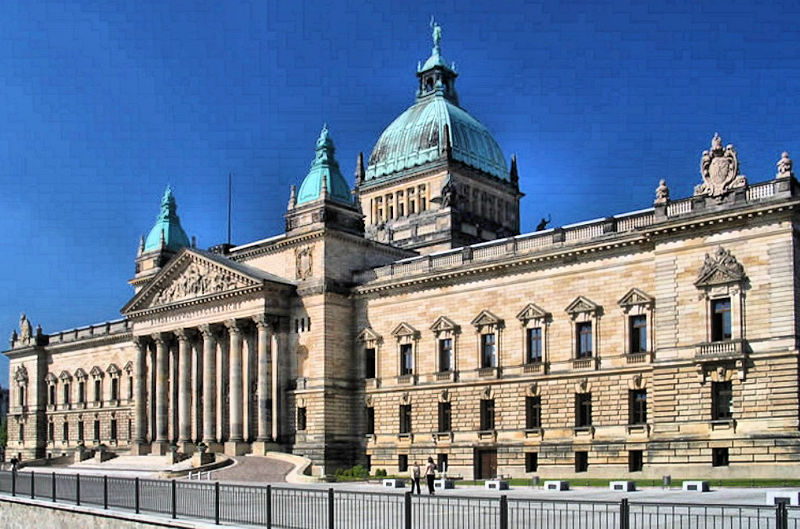

During the occupation years, Antwerp was used as a

logistical hub, a military supply depot and

manufacturing center, and also as an administrative

location for a separate military occupation entity apart

from the Etappe area and General Government. Due to

the proximity to the Dutch border, it was also a

notorious location for "spies," secret agents, persons of

dubious allegiance, members of various resistance cells,

and black market smugglers. So porous was the border

between occupied Belgium and the Netherlands, that in

1915 the Germans constructed an electrified barbed wire

fence between the two countries, a world premiere of

dubious accomplishment.

Belgium had never been self-sufficient in supplying

adequate amounts of food for its ever-growing

population, and the occupation years were especially

lean as not only imports were cut off but also local

agricultural production was faced with requisitions. If

not for Herbert Hoover's Committee for the Relief of

Belgium, starvation would have been rampant in the

country instead of "merely" severe shortages. Foodstuffs

donated by this committee were mainly shipped to

Rotterdam and from there transported by railway or

inland barge to Antwerp as one of the main distribution

points in Belgium. It was in many ways an asset for the German Army.

As an ocean port, not much at all happened during the war due to the effective British blockade. However, Antwerp was also an important inland waterway port, with barges running all over the place into northern France and the Netherlands, and Germany itself. So that was still in business but at a lower key of course.

And then there was heavy manufacturing in Antwerp, shipyards (e.g. the Cockerill Yards in Hoboken), heavy metal machinery production such as the Minerva Motor Company that built luxury cars before the war and armored cars during the siege, and all kinds of ship repair facilities and other manufacturing facilities that could be put to use supplying German armed forces in one way or another, even breweries and industrial-scale bakeries.

There were railways leading to the Etappe and frontline areas and canals as well. Antwerp had grain storage facilities, mills, sugar refineries. It had had an oil storage capacity in Hoboken with huge tanks that were both shelled by the Germans during the siege and afterward destroyed by the Belgian Army during the retreat to the sea.

Antwerp was also a welcome location for German

soldiers to be stationed for periods of recuperation or to

go on leave. As mainly a self-respecting harbor city, it

boasted a gratifyingly abundant number of legal

brothels as well as cafés and drinking houses galore.

During the war German authorities also established an

official spy school in the city, taking over a teaching

institute for nurses in a fashionable city suburb in which

to house the personnel. Its most famous, or infamous,

member was a female German officer named Elsbeth

Schragmueller, nicknamed "Frau Doktor" by her adversaries.

She was credited with being an unscrupulous and immoral

instructor in the fine arts of espionage, employing all

manner of (mostly imagined) lewd and amorous techniques

to extract information from unsuspecting and naive

Allied officers and statesmen. Antwerp loomed large

in the often feverish imagination of many a British or French

counterespionage officer, and tall tales of the escapades

of the mysterious "Frau Doktor" abounded both during

and after the war, (a highly fictionalized movie about her

adventures as a spy was made in the 1930s.)

100 Years Ago:

|

Memorial Day 2021

The Entrance to the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery, Romagne, France (ABMC Photo)

I was saddened, but not surprised, to learn that the Memorial Day commemorations at America's overseas cemeteries will not be open to the public again this year due to the Wuhan

Flu. I've been able to attend a number of these over the years and have always found them moving and inspiring, especially the Marine Corps themed event at Aisne-Marne (Belleau Wood) Cemetery and the Air Force-supported event at St. Mihiel.

Here's a photo from one of those past Memorial Days:

Aisne-Marne Cemetery, Belleau Wood in the Rear, 1916

A World War One Documentary

6

This ten-minute newsreel film presents itself as authentic footage of the 1916 Battle of Verdun. Well, some of the footage might have been filmed on the Verdun battlefield after the 1916 battle, but I wouldn't look to this video for an authentic depicticion of the Great War's longest battle. It's patched together, I think, with footage from several other sectors. Nevertheless, it has some of the most outstanding action footage of the French Army I've seen. Some of the best segments show the actual firing of both rail-mounted and field artillery, the gathering of German prisoners of war, small scale attacks, and the frightening approach of an enemy barrage during which the French photographer either does not flinch or had set his camera on automatic while he was sheltering elsewhere. Well worth a look.

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon