July |

Access |

Highlighting the U-Boat War

It Started with Napoleon

Long-time readers of my publications know that I often return to the 19th Century to look at the roots of the First World War. In the January 2014 issue of Over the Top magazine, I tried to make the case that it all started when Bonaparte was driven from the battlefield at Waterloo. Here's some of what I had to say. I think much of it still stands up.

Napoleon Departs the Waterloo Battlefield

"Those monarchies tried to squelch the French Revolution and then organized to fight Napoleon. After

Waterloo, their threat was still Bonaparte, not the man himself, but the revolutionary change he

symbolized and any successors who might claim his mantle. More than any movement, it seems it was

the heavy-handed effort to prevent another Bonaparte and to arrest change, both liberalizing and

radical and violent, that created much of that tension and latent energy. That is why we chose to start

our presentation of the 99-year journey to the Great War at Waterloo on 22 June 1815 at the moment when

Napoleon entered his carriage to leave the battlefield." MH

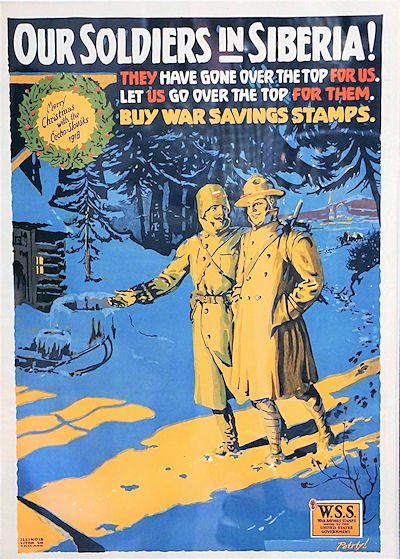

America's Siberian Intervention: Part 4 of 4,

|

||||||||||||||||

Not Forgotten at Home |

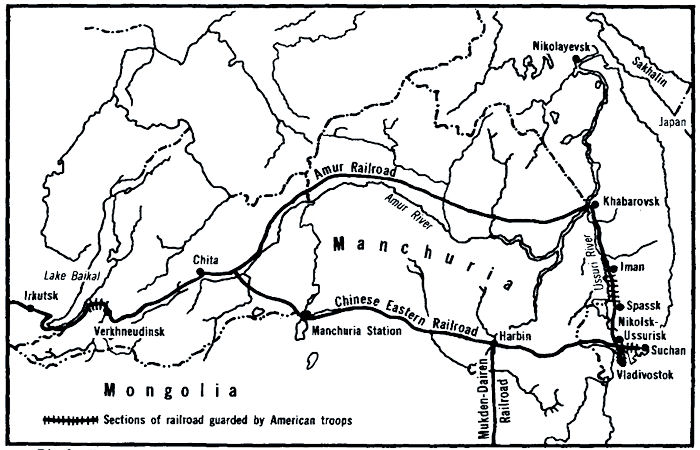

Without grace or glory, American forces left Siberia. The 27th and 31st Infantries returned to the Philippines. As Graves left with the last troops on 1 April 1920, a Japanese band played "Hard Times Come Again No More". The intervention, which cost the lives of 353 American soldiers (including 127 listed as killed in action despite suspicions that they had been taken as prisoners) was officially over.

The departure of the AEFS from the Siberian scene in March 1920 spelled the end of the struggle between Graves, Semenoff, and the Japanese for control of the Trans-Siberian Railway. Semenoff soon fled to Manchuria. The Japanese took over complete control of eastern Siberia and created a puppet state, the Far Eastern Republic, which lasted until 1922. The Communists ultimately triumphed in this area as well. Japanese forces left Siberia to wait for another day.

Years later, Secretary Baker confessed, "The expedition was nonsense from the beginning and always seemed to me one of those sideshows born of desperation." An insufficient number of troops, political misconceptions, a lack of military strategy all contributed to the failed intervention. And yet, the war against Bolshevism had every opportunity for victory. Trotsky remarked at the time, "When the Allies manage to act unanimously and undertake a campaign against us, all shall be lost."

Doughboys About to Board Their Ship for Departure

Meanwhile, Semenoff dispatched an agent to Washington to see if he could arrange political asylum and immigration to the United States for him. Upon learning of the visit, General Graves had a real chuckle. Graves noted that the requirements for legal immigration to the United States stated that an individual seeking asylum need to be mentally sound, morally clean, and physically fit. "If Semenoff was 'morally clean' then I never saw a human being who was not morally clean," wrote Graves. The U.S. Senate turned him down after extensive hearings revealed some of the atrocities he had committed while the ruler of the Trans-Baikal. Semenoff spent the majority of the 1920s and 1930s in Japan. He managed to remain hidden for some time until 1946 when Stalin's henchmen caught up with him and put him before a firing squad.

General Graves returned to the United States in 1920 and received the Distinguished Service Medal for his service in Siberia. Afterward, he held command positions in the Philippine Islands, New York, Chicago, and the Panama Canal Zone. After serving on the court-martial of Gen. Billy Mitchell in 1925, he retired from the Army in 1928 and died in 1940–the central figure in a most unusual chapter of the history of the United States Army.

Sources: Guarding the Railroad, Taming the Cossacks, U.S. National Archives; "AEF Siberia," The Doughboy Center

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

The Rise, Fall, & Rebirth

of the

U-boat

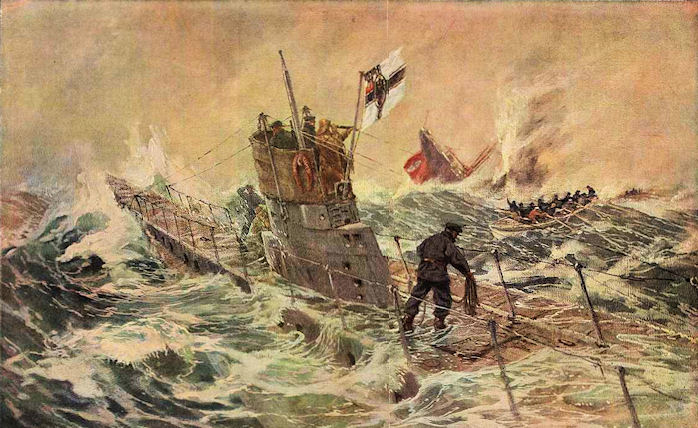

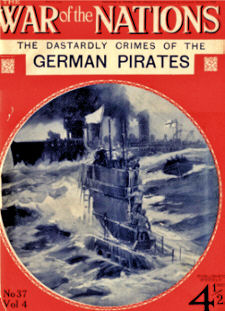

Pre-WWI predictions were mostly highly skeptical about the usefulness of submarines in future wars. British admiral Jackie Fisher did, however, point out that no successful antidote for the submarine had "been found even by the most bitter anti-submarine experts with unlimited means for experiments." The Imperial German Navy took Fisher's point and added a chaotic dimension to the war. The U-boat menace terrified the Allies, who needed over three years to find that antidote.

![]() U-Boats and the War at Sea

U-Boats and the War at Sea

![]() His Imperial German Majesty's U-Boats in WWI

His Imperial German Majesty's U-Boats in WWI

![]() The U-9 Shocks the Royal Navy

The U-9 Shocks the Royal Navy

![]() The Lusitania Controversy

The Lusitania Controversy

![]() Details on Every U-Boat Sinking of WWI

Details on Every U-Boat Sinking of WWI

![]() Germany Announces Resumption of Unrestricted Submarine Warfare

Germany Announces Resumption of Unrestricted Submarine Warfare

![]() Anti-Submarine Warfare and the Coming of the Convoy System (PDF Download)

Anti-Submarine Warfare and the Coming of the Convoy System (PDF Download)

![]() Dönitz and the Rebirth of the U-Boat for WWII

Dönitz and the Rebirth of the U-Boat for WWII

Winston Churchill Reflects on the War

11 November 1918

It was a few minutes before the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. I stood at the window of my room looking up Northumberland Avenue towards Trafalgar Square, waiting for Big Ben to tell that the War was over. My mind strayed back across the scarring years to the scene and emotions of the night at the Admiralty when I listened for these same chimes in order to give the signal of war against Germany to our Fleets and squadrons across the world. . . And then suddenly the first stroke of the chime. I looked again at the broad street beneath me. It was deserted. From the portals of one of the large hotels absorbed by Government Departments darted the slight figure of a girl clerk, distractedly gesticulating while another stroke of Big Ben resounded. Then from all sides men and women came scurrying into the street. Streams of people poured out of all the buildings. The bells of London began to clash. Northumberland Avenue was now crowded with people in hundreds, nay, thousands, rushing hither and thither in a frantic manner, shouting and screaming with joy. . . After fifty-two months of making burdens grievous to be borne and binding them on men’s backs, at last, all at once, suddenly and everywhere the burdens were cast down.

In Winston S. Churchill, volume IV World in Torment 1916-1922, by Sir Martin Gilbert.

AEF Battlefields

Gallipoli

From: Valor Tours, Ltd. / Mike Grams, Tour Leader

When: September 2019

Details: Request brochure via Email

HERE.

From: National World War I Museum / Clive Harris & Mike Sheil, Tour Leaders

When: October 2019

Details: Itinerary and Tour FAQ

HERE.

French Army Mutiny:

The Numbers

The first incidents of disobedience occurred on 16

April, the first day of the ground attack in Nivelle's

offensive. Guy Pedroncini, who has published a

detailed study of the “mutinies,” identified six soldiers

from the 24th Infantry Division who “abandoned their

post” on the first day of the ground attack. Other

incidents occurred in subsequent days, but according

to the French Service historique in the official history of

the war (published in 1936), the real acts of “collective

indiscipline” began on 29 April. It identified 119 cases

of collective indiscipline through September, 110 of which they considered “grave,”

and an additional 51 that were not considered

“collective,” for a total of 170 incidents.

Elementary: The U-Boat Threat Identified

The most accurate prewar prognosticator of the threat presented to England by German U-boats was none other than Arthur Conan Doyle. After visiting Germany in 1911, Conan Doyle began to study German war literature. He saw that the submarine and the airplane were going to be important factors in the next war. He was particularly concerned about the threat of submarines blockading food shipments to Britain.

“Danger!” (The Strand Magazine, July 1914)

Doyle’s proposals, given voice in the imagined Times leader, included: reformation of agriculture and trade policies to provide “sufficient food to at least keep life in her [Britain’s] population;” construction of “two double-lined railways under the Channel” to facilitate movement of goods and, presumably, armies; and “the building of large fleets of merchant submarines for the carriage of food.” Clearly, Doyle’s major concern was with having enough food to feed the nation during hostile times.

Convinced that this was a vital precaution, Conan Doyle eventually took his idea to the public in the form of a story, "Danger! Being the Log of Captain John Sirius" that originally appeared in the July 1914 edition of The Strand Magazine. The story dealt with a conflict between Britain and a fictional country called Norland. In the story, Norland is able to bring Britain to its knees by the use of a small submarine fleet. Its opening passage was an eye-opener:

It is an amazing thing that the English, who have the reputation of being a practical nation, never saw the danger to why they were exposed. For many years they had been spending nearly a hundred million a year upon their army and their fleet. . . Yet when the day of trial came, all this imposing force was of no use whatever, and might as well have not existed.

Sadly, Conan Doyle's warnings were ignored, at least by the British. German officials were later quoted as saying that the idea of the submarine blockade came to them after hearing Conan Doyle's warnings against such an event. How much of that statement was truth and how much was propaganda designed to cause conflict within Britain is not known.

From: Continuum, Newsletter of the University of Minnesota Libraries

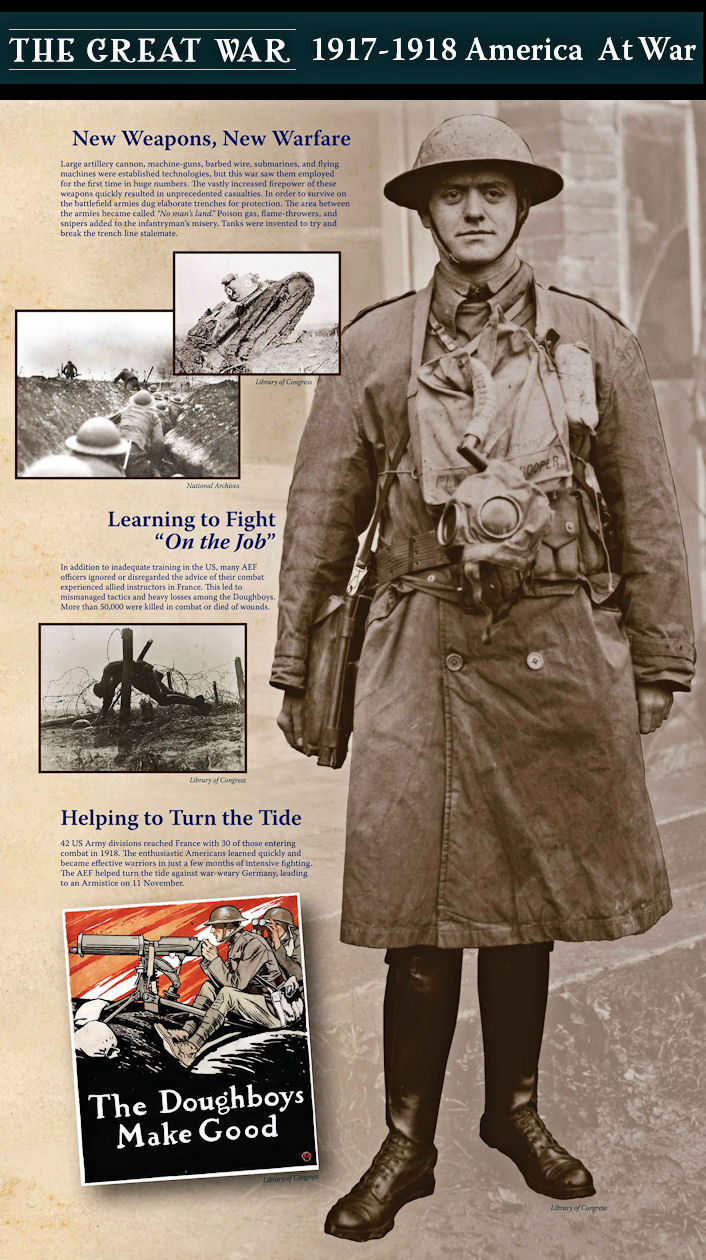

Looking Back: A Retrospective of the War

Part VI

This is our seventh historic banner provided by the San Francisco War Memorial's World War I Armistice Centennial Commemorative Committee. Thanks to Dana Lombardy, who led the effort to produce these. Visit HERE to learn more about the commemorative exhibition being held in the City by the Bay.

The Machine Gun Shaped the Great War

From the Infantry Journal

Enhanced German Machine Gun Outpost

Artillery may have been the greatest killer of the First World War, but it was the machine gun that shaped the way the war was fought. This is the argument that U.S. Army Major Jack R. Northstine made in a recent issue of Infantry.

. . . The defensive power of the machine gun created

the stalemate on the Western Front, and almost all of the

technologies that were introduced during the war were built

in order to defeat it. The introduction of this weapon radically

changed the strategies and tactics used by militaries in the

future.

The Franco-Prussian War and the Russo-Japanese War are the

two most significant wars that influenced military theorists prior to the Great War. These wars revealed the improvements made in artillery and small arms. The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 demonstrated the impact of the machine gun and revealed two important lessons:

* First, that use of the machine gun in the defense resulted in the digging of trenches, and

* Second, that machine guns could be used to decimate a far larger offensive force as was demonstrated by the Japanese use of the

Hotchkiss gun.

World militaries were not ignorant to these lessons, but they tended to view the battlefield developments as proof of Russian military weakness and not the result of the inherent defensive power

of the machine gun or the inevitability of trench warfare.

Instead, the European militaries were influenced primarily by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. This war occurred in Europe and had been won using classic maneuver and encirclement tactics. It became the archetype for all of the European powers—particularly France and Germany—on how to conduct a successful military campaign. The major powers of the Great War failed to understand that in the

43 years since the Franco-Prussian War, technology had developed in such a way as to make previous tactics obsolete, as demonstrated in the Russo-Japanese War. These militaries envisioned a highly mobile offensive as the key to success in future battles. France was soundly defeated and humiliated at the Battle of Sedan (Franco-Prussian War, September 1870), and the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine were annexed.

British Machine Gunners in Flanders

Joffre [commander of French military] was an ardent admirer of the all-out offensive, l’offensive à outrance. He vowed never again to allow a French army to be encircled as at Sedan. It was from these origins that

the spirit of the offense became the cornerstone of all the major

powers’ military strategies. Prior to the Great War, a Polish writer named Jean de Bloch wrote a book arguing that “the increased firepower of infantry weapons would force troops to dig in for defense. Between

the trenches, a fire swept zone would be created which could be crossed only at the cost of devastating losses.”

Although his prediction turned out to be remarkably accurate, the professional militaries of the time dismissed his claims, citing once again the importance of troop morale and offensive spirit. History seems to judge France particularly harshly when regarding its reliance on the

offensive spirit (élan). It is true that the French believed that

it was the offensive spirit that would win battles, but in reality,

all of the European powers were duped into the belief that the

spirit of the infantry would be able to break a fortified defense.

They all believed it would be the power of their offense that

would be decisive in future wars.

When the Great War began in 1914, the attacks were linear

in nature and based on prewar theories which didn’t account

for the machine gun. Each battalion advanced shoulder to

shoulder with a screen of skirmishers out front. Once the main

force made contact with the enemy, reserves were fed into

the battle in order to fill the gaps created by casualties. The

advancing force had two objectives: to suppress enemy fire

and inflict sufficient causalities in order to make the opposition

waiver. Then, theoretically, once the enemy began to waver,

a bayonet charge would deliver the final blow. “Victory would

result, therefore, not from superior tactics, or even superior

weaponry, but from the imposition of superior will.”

In reality, attacks very rarely ever culminated in a bayonet charge.

Much has been made of the battles of attrition, such as

Passchendaele, Verdun, and on the Somme that occurred

later in the Great War. Often the initial battles, which were not

fought from trenches, have been forgotten. The impact of the

machine gun was felt early on, and the result was the largest

number of losses during the war. “The enormous losses in

August and September 1914 were never equaled at any

other time, not even at Verdun: the total number of French casualties (killed, wounded, or missing) was 329,000. At the

height of Verdun, the three-month period February to April

1916, French casualties were 111,000.

It was the impact and associated losses of the machine gun that drove the major combatants into the trenches. The machine gun came

to represent the use of technology applied to weaponry. The

power it gave to a single man made the offensive doctrine

of the European powers obsolete, forcing the armies on the

Western Front into trenches. All of the combatants were left

with the option to dig in or be annihilated.

Turkish Machine Gun Team at Gallipoli

The primary reason the machine gun caused trench

warfare was that the weapon was defensive. The Maxim and

Hotchkiss models were significantly smaller than previous

models, but they were still heavy by modern standards. The

German Maxim 08 weighed between 136.4 to 146.3 pounds.

and required at least six men to carry it and its ammunition.

The French and British machine guns of 1914 were not

much better: the French Hotchkiss weighed 103.4 pounds

and the British Vickers-Maxim 118.8 pounds.

This meant that the machine gun could only be utilized in a defensive

role because it was far too heavy to incorporate in a highly

mobile offensive manner. The results were catastrophic and

completely unforeseen by the military leadership. Sir John

French, commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF),

captured the bewilderment of the now-engaged European

militaries when he said, "I cannot help wondering why none

of us realized what the modern rifle, the machine gun, motor

traction, the aeroplane, and wireless telegraphy would bring

about."

By 1915, a series of trenches stretched from the English

Channel near Ostend to the northern border of Switzerland.

This situation would remain relatively unchanged until 1918.

. . . There were a number of technological advances introduced

during the Great War, but the machine gun was the most

decisive. WWI European powers failed to recognize how the

machine gun would impact their tactics; they all believed it

would be the power of the offense that would be decisive in

future wars. They were proved wrong in numerous battles

which resulted in significant loss of life for minimal territorial

gains. Ultimately, it was the implementation of small unit tactics

developed by the Germans—not the grand offensives of the

Allies—that provided the best solution. The machine gun was

the decisive weapon of the Great War, and its introduction

to the battlefield would radically change the strategies and

tactics used by militaries in the future.

Source: Infantry Journal, August 2009

Read Major Nothstine's full article

HERE.

Final Issue of Stars and Stripes

13 June 1919

100 Years Ago:

|

|||||||||||||

|

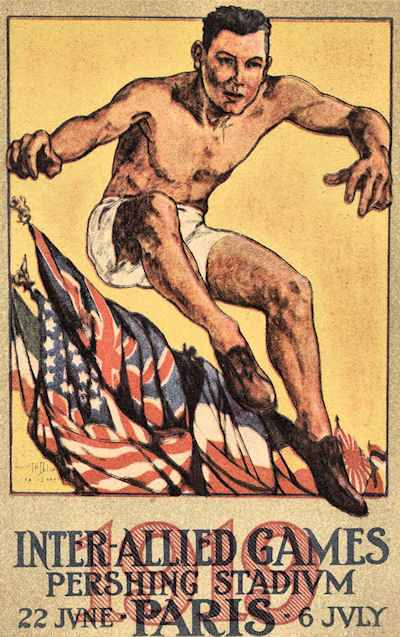

Discharging the 1.5 million men still in the U.S. training camps was a relatively easy proposition, and most were headed home by February 1919. This was not true for overseas soldiers, and discontent grew over the delay in getting them back home. Authorities, concerned that peace negotiations might break down and the army would be forced to fight again, imposed a steady diet of daily drills, target practice, and tactical exercises. Low morale over the continued training and the slow pace of demobilization reached near crisis proportions just as a third wave of influenza hit the debarkation camps in France. This created tremendous bitterness among troops who watched their comrades fall ill and die while awaiting transport home.

Clearly, something voluntary and enjoyable was needed to unite the troops and occupy their time until the War Department could get them all home. Sports competitions offered the ideal solution.

| Participating Nations |

U.S.A. Australia Belgium Canada Czechoslovakia France |

Greece Hedjaz (Arabia) Italy Newfoundland New Zealand Portugal |

Romania Great Britain (rowing & golf only) China and Guatemala (ceremony only) |

The American Delegation at the Opening Ceremonies

| Events |

Baseball Basketball Boxing(bantam to heavyweight) Fencing (foils, sabers, épée) Horseriding (known then as Equitation) |

Football (rugby style) Golf Hand Grenade Throwing Rowing (single sculls, four and eight-oared) |

Tug-of-War Shooting: Army Rifle and Pistol Swimming Tennis Track and field Wrestling (bantam to heavyweight) |

An Olympics-style opening ceremony featuring more than 1,500 participants was held and athletes from 14 nations competed. Competitions were held in a number of sports, including baseball, basketball, boxing, football, golf, swimming, track and field, tennis and even hand grenade tossing. Participants included several famous tennis players, including previous/future Wimbledon champions Andre Gobert (France), Randolph Lycett (Australia) and Pat O’Hara Wood (Australia).

The large American contingent dominated the competition. The boxing competition featured future world heavyweight champion Gene Tunney. Future wrestling world middleweight champion Ralph Parcaut (U.S.) competed, and future president of the National Boxing Association (later the World Boxing Association) Paul Prehn captured the middleweight gold medal in wrestling.

In the service shooting events, the AEF men were successful with both rifle (with the Springfield rifle) and pistol, taking four first places. Other first places were gained by the U.S. in baseball, basketball, boxing, equestrian jumping, swimming, and freestyle wrestling. In the tug-of-war finals, the Yanks prevailed against a Belgian team.

The Swimming Competition

World-class sprinter Charles

Paddock, who would win two gold medals at the Antwerp Olympics, was the star of the

track meet. U.S. Army chaplain F.C. Thompson set a world record in the newly created sport of hand grenade tossing with a mark of 245 feet, 11 inches. An article in the New York Times, dated 6 July 1919, stated that the crowd at the Inter-Allied Games “loudly cheered the negro private Solomon "Sol" Butler, the American broad jump champion.”

Arguably the greatest individual achievement came from American swimmer Norman Ross, who won the 100m, 400m, and 1,500m freestyle events, the latter in a world-record time of 5 minutes, 40 seconds. Ross eventually won three Olympic gold medals and set 13 world records during his career.

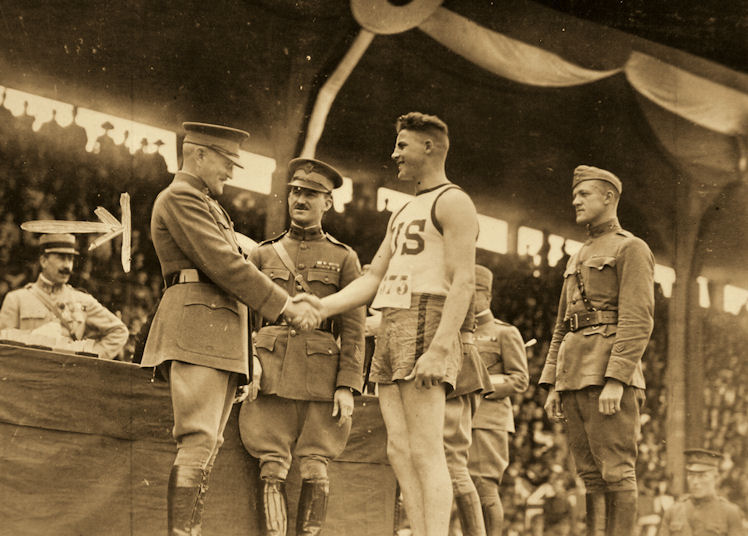

General Pershing Congratulates a Doughboy Medal Winner

After more than two weeks of competition, the event concluded with an extravagant closing ceremony on 6 July. Bands in the crowded stadium played the “Star-Spangled Banner” followed by the “Marseillaise,” and the flags of the Allies were slowly lowered with more than 30,000 spectators witnessing the stadium being gifted to France. On that last afternoon, prizes were awarded to the winners by General Pershing and the French flag, alone, was hoisted over Pershing Stadium for the first time.

The Inter-Allied Games, one of the most unique athletic events ever contested, served as a fitting testament to the conclusion of World War I–the first conflict in human history in which every inhabited continent participated, resulting in destruction and carnage, unlike anything the world had ever seen. The following year the Olympics would be restarted in Antwerp, selected in honor of its suffering and surviving enemy occupation for nearly the entire war. By one estimate, almost 10 percent of the competitors at Antwerp were veterans of the Inter-Allied Games.

Main Article and Images Provided by Mike Vietti of the National WWI Museum and Memorial

25 April 2019: The 104th Anniversary of Anzac Day, Commemorated at Lone Pine Cemetery and Memorial, Site of One of the Fiercest Battles of the Gallipoli Campaign (TRT World Photo)

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications |

||

Order Our

|

Shop at |

Order the Complete Collection

|

A World War One Film Classic

This is a beautifully-done, mostly-factual, depiction of the romance between wounded and very young ambulance driver Ernest Hemingway and 26-year old nurse Agnes von Kurowsky. The relationship deeply affected Hemingway's life and writings, most notably his World War I novel A Farewell to Arms. The late Richard Attenborough directed an authentic-feeling film to view, and the lead actors are totally believable in their roles, Chris O'Donnell as Ernest, and Sandra Bullock–in one of her most engaging performances–as Agnes. On the downside of things, there's probably more sex in the film than actually occurred, but the biggest problem is with the ending. It features Agnes making a fictional postwar visit to the States to terminate the affair with Ernest face-to-face. Despite this jarring conclusion (for anyone familiar with the story) In Love and War is a must-see for any World War I aficionado. The film is available on Netflix and for purchase on Amazon.

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon