July

2020 |

|

|

|

Those Volunteer Ambulance Drivers

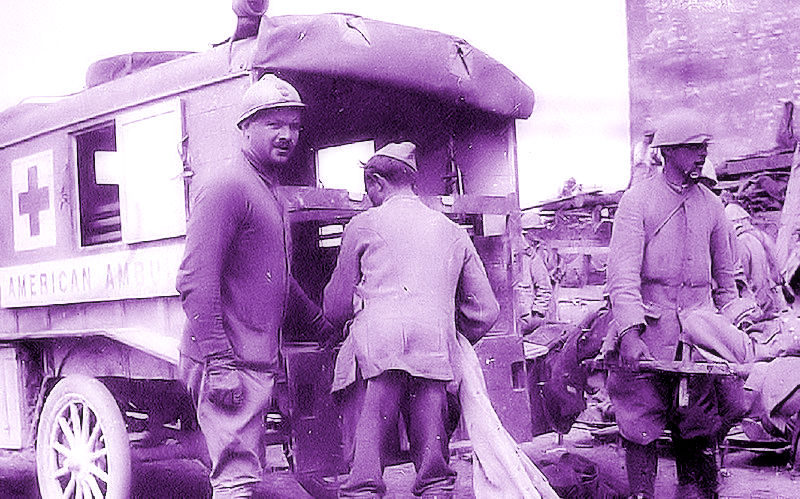

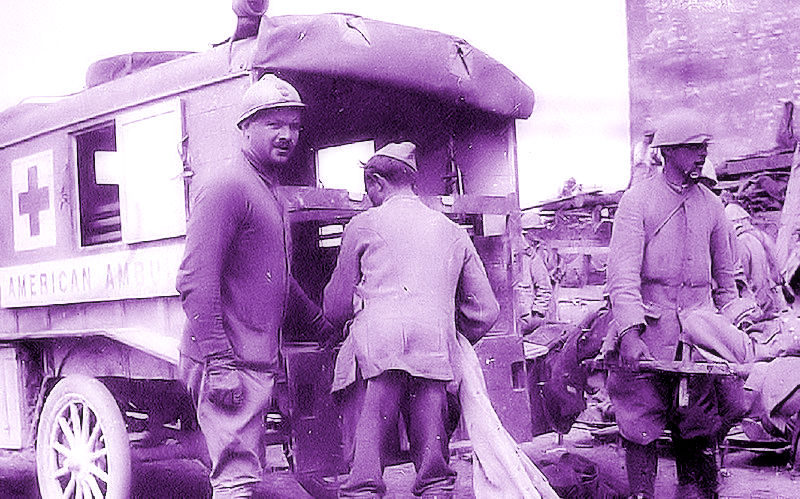

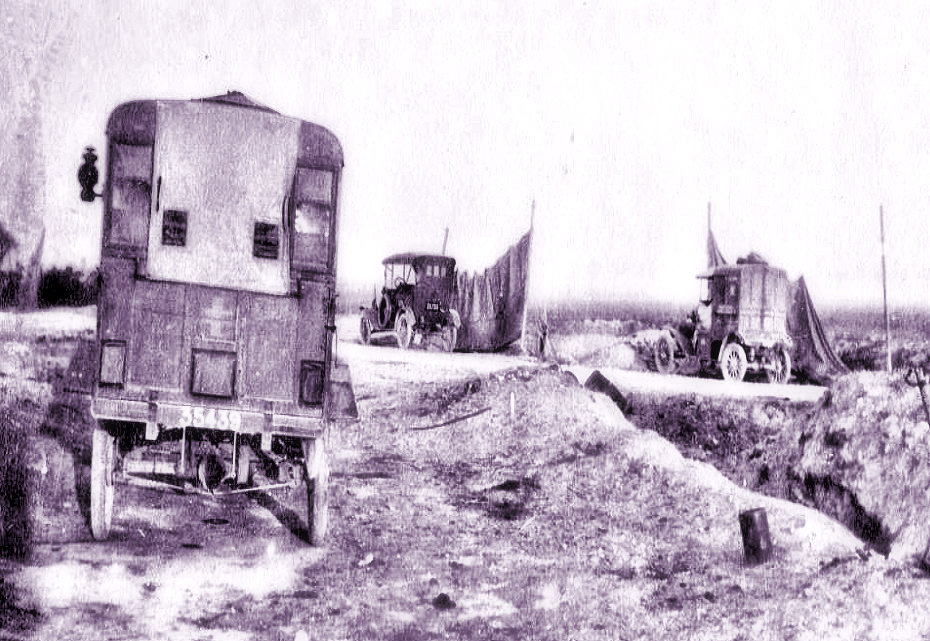

American Field Service Ambulance, Verdun Sector

While the United States remained a neutral power up to April 1917, American volunteers

contributed a total of over 3,500 personnel to ambulance work between 1914 and 1917,

primarily serving with the French Army. Three principal ambulance corps were involved: the

American Field Service, the Harjes Formation, and the "Anglo-American" Corps, as well as a number of smaller units. Around one third went on to serve in the American Expeditionary Force and other Allied armies and air services. By the way, it's probably no accident that America's Last Doughboy was an ambulance driver. Seventeen-year-old Frank Buckles wanted to get Over There to see the Big Show. He asked around and discovered the fastest way to get to France was to enlist as an ambulance driver, so he lied about his age and enlisted in the U.S. Army Ambulance Service. And, indeed, he got Over There, later to become an outstanding representative of his generation.

Our principal contributor to the story of the volunteer ambulance drivers is British journalist and author Patrick Gregory, who has been a past contributor to theTrip-Wire and our daily blog Roads to the Great War. He is also the co-author of An American on the Western Front, the story of Arthur Clifford Kimber, a Stanford University student, who volunteered as an ambulance driver, helped carry the first official American flag to the battlefields of Europe, and eventually died in action as a pilot with the U.S. Air Service (LINK)

Patrick's three-part article in this issue originally appeared in the 1914-1918 Online International Encyclopedia of the First World War. MH

The U.S. Volunteer Ambulance Services

Patrick Gregory

Part 1: Multiple Origins

American Drivers from the Norton-Harjes Group

American war volunteering efforts in Europe began as soon as hostilities commenced in early

August 1914, centering in large part on ambulance and other medical relief initiatives in France. Most

of these efforts had an early association with the original American Hospital, founded four years

earlier in Neuilly in Paris. Members of the expatriate American business community and individuals

in and associated with the US embassy helped coordinate relief efforts and donated cars, money, and equipment.

In order to be able to treat battlefield wounded, a second institution, the American Ambulance

Hospital (or American Military Hospital) was established on 9 August 1914, also in Neuilly, at the

Lycée Pasteur. It had the backing of a number of prominent figures including Myron Herrick (1854-

1929), the US ambassador in the early months of the war; his wife Carolyn "Kitty" Herrick (1855-

1918); wealthy donors such as Anne Harriman Vanderbilt (1861-1940); and Herrick’s immediate

predecessor as ambassador, Robert Bacon (1860-1919). The hospital was soon treating wounded

soldiers ferried from the front during the First Battle of the Marne in early September. The work was

aided by volunteer ambulance drivers, often young Americans who found themselves in Europe at

the commencement of war; and it was in this direction of ambulance transport that relief efforts would increasingly focus.

In the latter part of 1914 and early 1915, three distinct ambulance units emerged: the Harjes

Formation or Morgan-Harjes Ambulance Corps founded by H. Herman Harjes (1872-1926), senior

partner of the Morgan-Harjes investment bank (an early French subsidiary of Morgan Stanley); the

American Volunteer Motor Ambulance Corps or "Anglo-American" Corps of the American

archaeologist Richard Norton (1872-1918); and the third, the American Ambulance Field Service,

later shortened (in summer 1916) to "American Field Service" or AFS.

American Ambulances in Italy

In early October 1914 Harjes and his wife Frederica Berwind Harjes (1877?-1954), a member of the

American Ambulance Hospital board, set up a mobile field hospital comprising several surgeons,

orderlies, and drivers and set off to work in the Compiègne-Montdidier sector north of Paris,

providing medical assistance for the French army. Their work continued through the autumn and

winter of 1914-15 but increasingly, with more use by the French authorities of the mobile ambulance

aspect of their operation, the drivers and vehicles began to operate independently of the medical

facilities. In turn, more young American men were attracted to volunteer for work in this more active

role. Harjes dropped the hospital branch in mid-February 1915.

An element of ambulance duty that began to cause frustration for Harjes drivers and those of the

other corps now operating in the field was that the French Army was reluctant to allow the Americans

to operate in or from frontline postes de secours (advanced dressing stations), given their status as

nationals of a neutral power. The French feared that volunteers might harbor pro-German

sympathies. Instead, the drivers were restricted to more routine "jitney" work, ferrying the sick and

wounded from incoming sanitary trains to hospitals in rearguard towns and cities.

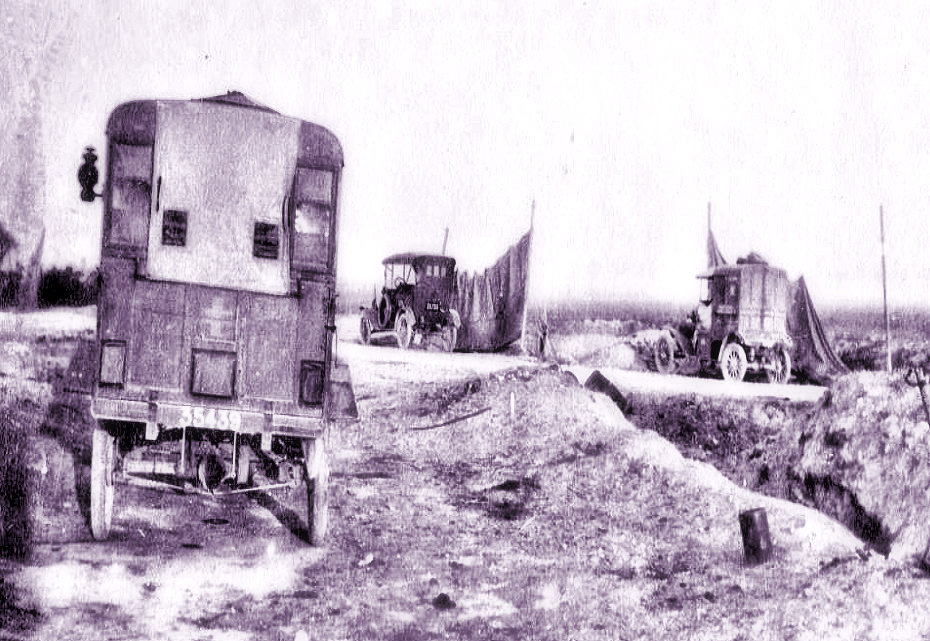

American Ambulances on the Champagne Battlefield

East of Reims

Richard Norton’s "Anglo-American" Corps began around the same time as Harjes and allied itself

with the British Red Cross (BRC) after the American Ambulance Hospital refused to sponsor it. The hospital was initially unwilling to develop a large ambulance wing. The BRC helped underwrite some

of Norton’s operating costs and used the corps to distribute supplies. Although technically attached

to the BRC in Boulogne, the corps carried out most of its work in the following months under the

auspices of the French Second Army some seventy miles to the south-east. Norton’s relationship

with the BRC was a strained one, with Norton finding his sponsor inflexible and administratively

cumbersome. By December 1915 he joined Harjes – who had begun such a relationship six months

earlier – in forging a link with the American (National) Red Cross (ANRC or ARC) instead. At the end

of 1916 the Harjes and Norton corps merged into one ambulance unit, the Norton-Harjes Formation

under the ARC banner.

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

|

|

Different Perspectives

The volunteer ambulance drivers of the First World War have a special place in literary history. As a group they were exceptionally highly educated and included many members who wrote well. As one of their members, Malcolm Cowley, put it, "The ambulance corps and the French military transport were college-extension courses for a generation of writers." Furthermore, many were idealists, looking to make a better world, who had their hopes shattered observing the carnage of the war firsthand. Consequently, they were well represented in the "Lost Generation" of the 1920s.

Literary Ambulance Drivers

Literary Ambulance Drivers

The American Volunteer Motor-Ambulance Corps: A Scholarly Assemblage

The American Volunteer Motor-Ambulance Corps: A Scholarly Assemblage

World War One Diaries from the AFS Archives

World War One Diaries from the AFS Archives

Rhymes of a Red Cross Man by Robert Service

Rhymes of a Red Cross Man by Robert Service

A Wounded Ernest Hemingway Writes Home

A Wounded Ernest Hemingway Writes Home

The Women Who Drove Ambulances on the Western Front

The Women Who Drove Ambulances on the Western Front

Personal Letters of a Driver at the Front

Personal Letters of a Driver at the Front

How Ambulance Drivers Hemingway and Dos Passos Rerouted the Course of American Literature

How Ambulance Drivers Hemingway and Dos Passos Rerouted the Course of American Literature

Fany (First Aid Nursing Yeomanry) at the Western Front

Fany (First Aid Nursing Yeomanry) at the Western Front

"Was It a Dream," by Driver Amos Wilder

"Was It a Dream," by Driver Amos Wilder

Jerome K. Jerome on the Western Front

Jerome K. Jerome on the Western Front

Dear Family

When I come back to you some day, we shall feel a greater peace and sympathy for knowing that with the same eagerness, if in different ways, we have tried to serve and to save those men whose heroism makes our best effort seem a very small thing.

Letter, Leslie Buswell,

Ambulance No. 10

Driving Skill

The automobile was so new that many of the young men had to learn to drive before they could serve. "I'm going to France with the Norton-Harjes as soon as I can take a course in running a machine," wrote John Dos Passos in a personal letter.

(Firstworldwar.com)

Charles Nordhoff

Ambulance Driving Memories:

The first published work by ambulance driver/ aviator/ and author Charles Nordhoff was a war memoir title The Fledgling that focused on his days flying with Escadrille SPA 99 of the Lafayette Flying Corps. Some reflections on his earlier service as an ambulance driver with the American Field Service worked its way into the narrative:

I was on the road all day yesterday, afternoon and evening, getting back to the post at 10 P.M. One of the darkest nights I remember – absolutely impossible to move without an occasional clandestine flash of my torch. Far off to the right (twenty or thirty miles) a heavy bombardment was in progress, the guns making a steady rumble and mutter. I could see a continuous flicker on the horizon. The French batteries are so craftily hidden that I pass within a few yards of them without a suspicion. The other day I was rounding a familiar turn when suddenly, with a tremendous roar and concussion, a "380" went off close by. The little ambulance shied across the road and I nearly fell off the seat. Talk about "death pops"-these big guns give forth a sound that must be heard to be appreciated. . .

The siege warfare to which, owing to strategic reasons, we are reduced in our part of the lines, with both sides playing the part of besieged and besiegers, gives rise to a curious unwritten understanding between ourselves and the enemy. Take the hospital corps, their first-aid posts, and ambulances. The Germans must know perfectly well where the posts are, but they scarcely ever shell them-not from any humanitarian reason, but because if they did, the French would promptly blow theirs to pieces. It is a curious sensation to live in such a place, with the knowledge that this is the only reason you enjoy your comparative safety. Likewise our ambulances. I often go over a road in perfectly plain view of the Boche, only a few hundred yards distant, and though shells and shrapnel often come my way, I am confident none of them are aimed at me. The proof of it is that no one has ever taken a pot-shot at me with rifle or machine-gun, either one of which would be a sure thing at the range.

Source: The Fledging by Charles Nordhoff

Doughboys in the Meuse-Argonne

Detail, Lost Battalion Memorial

Charlevaux Mill, France

From: Lost Battalion Tours / Rob Laplander & Mike Cunha, Tour Leaders

When: 8-15 August 2020

Details: Download Flyer

HERE.

|

|

Part 2: The American Ambulance Field Service

American Field Service Director A. Piatt Andrew and Future Director Stephen Galatti

The work of the American Field Service, meanwhile, grew more directly and organically out of the

American Ambulance Hospital in Neuilly. Differences remained between those on its board who

wished to concentrate on core hospital work and others who saw the practical value of a mobile

service. (The "Ambulance" in the hospital title had the association in France more akin to that of a

military hospital than an emergency vehicle.) But by late autumn 1914 its cars were allowed out into

the field to serve regional hospitals.

The AFS became the largest of the volunteer ambulance services, expanding rapidly with the arrival

at the turn of 1914/1915 of A. Piatt Andrew (1873-1936), a former assistant secretary of the U.S.

Treasury, who was to become the AFS director. Andrew extended the scope of his operation and

eventually separated completely from the Ambulance Hospital in 1916. He developed the role of all

the different volunteer corps in the field by persuading the French authorities in April 1915 to allow the volunteers of the three American services to function immediately behind frontline trenches in

battlefield areas.

As such, units of 25 to 30 men and some twenty ambulances were each assigned to

individual French divisions, becoming the divisions’ principal ambulance service. Separate camion

truck supply units were added, also manned by volunteers. They were to serve with the French

across the Western Front and, in the case of two units of the AFS, with the French Army of the

Orient in the Balkans.

A principal source of recruitment for the services came from American colleges, with east coast Ivy

League institutions such as Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Dartmouth, and Cornell well represented plus

west coast universities such as the University of California (Berkeley), and Stanford. The colleges alone

contributed some 1,855 men to the American Field Service, aided in the U.S. by the recruitment

efforts of Henry Sleeper (1878-1934), a friend of Piatt Andrew. AFS medical director Edmund Gros (1869-1942) also helped recruit AFS volunteers and others into the French legionnaire Lafayette

Escadrille and Lafayette Flying Corps.

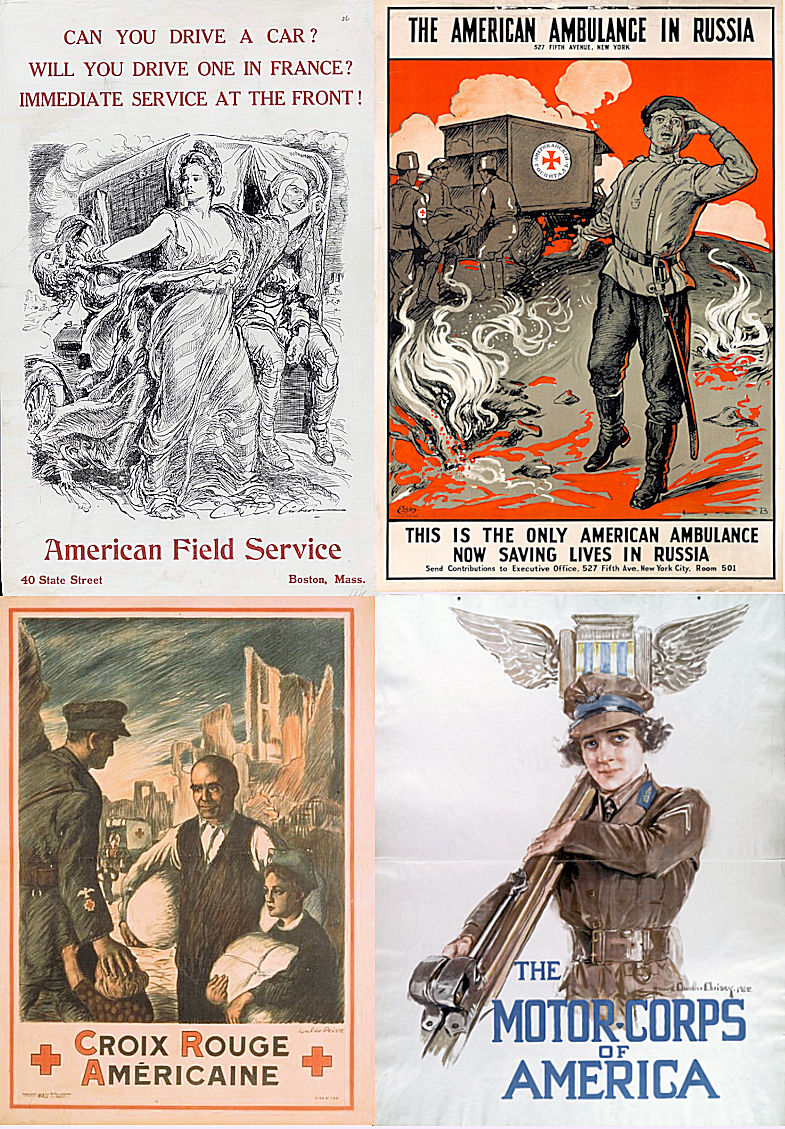

Part 3: America Enters the War

U.S. Army Ambulance Drivers in Training

The volunteers continued in service under their own auspices until the US entered the war in April

1917, when they were amalgamated in October 1917 into the United States Army Ambulance

Service (USAAS) and AEF Transportation Division. At the time of handover, the American Field

Service comprised 33 sections (34 at its peak) with some 1,200 ambulance

volunteers, almost 1,000 ambulances, 14 camion sections, and 800 camion drivers. The

combined Norton-Harjes Formation strength reached 13 sections, over 100 ambulances, and

200 men. Only around 500 volunteers transferred over to USAAS; however, the majority of them

from the AFS. Nearly 1,000 former AFS volunteers went on to serve in American Expeditionary

Force units, US Air Service, and US Navy, as well as French and British forces.

Leading the French military mission visit to the U.S. in May 1917, Marshal Joseph Joffre (1852-1931)

specifically highlighted the work and model of the volunteer ambulance services, identifying the

continued supply of ambulance units to the French army as a priority area. Mobilization by the US

Medical Department of the United States Army Ambulance Service was consequently swift and from

the outset continued the previous policy of accepting whole volunteer units raised by colleges, as

well as others raised by cities and corporations.

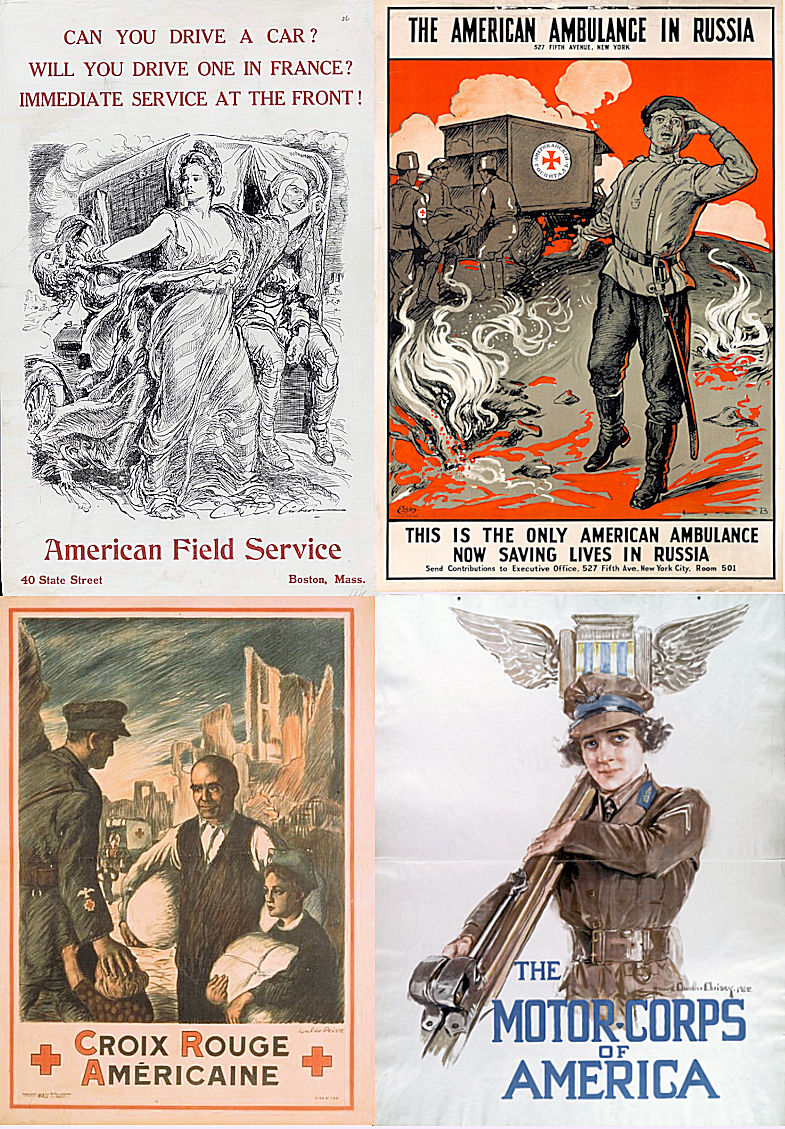

Recruiting Volunteer Ambulance Drivers

Volunteer James Rogers McConnell

Ambulance Driver & Aviator

McConnell, American Field Service Driver

James Rogers McConnell was born in Chicago, Illinois, the son of a prominent judge, in 1887. The family later moved

to North Carolina. McConnell attended private schools throughout his childhood and went to college at the

University of Virginia. He attended law school briefly and then worked in several business ventures back home in North

Carolina.

A family friend described McConnell’s “adventurous spirit,” which led him to volunteer in 1915 for the American

Ambulance Field Service, a volunteer ambulance corps newly founded by Americans in Paris that same year (later

called the American Field Service or AFS). As an ambulance driver, McConnell gathered injured men from the

battlefield and brought them for treatment to military field hospitals. After bravely serving for a year, he earned the

distinguished Croix de Guerre medal from the French government for courage under fire.

Increasingly passionate about defending France, however, McConnell had begun to consider leaving the noncombatant ambulance service to enlist as a volunteer with the French military. The newly created Lafayette Escadrille provided him

the opportunity to do so.

McConnell in the Cockpit of a Nieuport 11

The Lafayette Escadrille was a group of American pilots serving with the French Air Service (Aéronautique Militaire) prior to the entry of the United States into the war. Authorized by the French government in the spring of 1916, the group was named in honor of the Marquis de Lafayette, considered by many to be a French hero who helped win the war for the American colonists during the American

Revolution. The pilots wore fur-lined uniforms to keep

them warm in the fragile planes, often going out on two-hour

patrols.

Thirty-eight Americans served in the Lafayette Escadrille,

many of whom became famous on the home front for

their dangerous volunteer service. McConnell wrote a

book about his experiences during the war titled Flying

for France (1916); it helped Americans at home understand the

kind of service they were doing overseas on the side of

France and built support for the U.S. to enter the war.

Volunteering as a military pilot for France allowed

McConnell to take sides in what he saw as a righteous

cause. It also gave him the privilege of learning to fly. As

he wrote about flying for the French Air Service in his

book, “It was the beginning of a new existence, the entry

into an unknown world. . . For us all it contained unlimited

possibilities for initiative and service to France.”

Casualties in this type of volunteer service

skyrocketed during the war, as air-to-air combat

increased. McConnell’s plane was shot down

on 19 March 1917, during aerial combat with two

German planes. McConnell was killed just weeks

before his government joined the Allied cause in

Europe as a combatant nation.

Source: The Volunteers: Americans Join World War I, 1914-1919, AFS International

|

100 Years Ago:

France Enforces Its Mandate in Syria

French Representative General Henri Gouraud Announces Creation of Lebanon As Independent Nation

In November 1918, Britain and France declared their intention of establishing in Syria and Iraq “national governments drawing their authority from the initiative and free choice of the native populations.” By the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, France was to be free to establish its administration in Lebanon and on the coast and to provide advice and assistance to whatever regime existed in the interior. In March 1920 a Syrian Congress meeting in Damascus elected Faisal king of a united Syria including Palestine; but in April the Allied Conference of San Remo decided that both should be placed under the new mandate system and that France should have the mandate for Syria. In June 1920 a French ultimatum demanding Syrian recognition of the mandate was followed by a French occupation and the expulsion in July of Faisal.

The mandate placed on France the responsibility of creating and controlling an administration, of developing the resources of the country, and of preparing it for self-government. A number of local governments were set up: one for the Al-Anariyyah Mountains region, where the majority belonged to the Alawite sect, one for the Jabal al-Duruz region, where most of the inhabitants were Druze, and eventually one for the rest of Syria, with its capital at Damascus. The French mandatory administration carried out much constructive work. Roads were built; town planning was carried out and urban amenities were improved; land tenure was reformed in some districts; and agriculture was encouraged, particularly in the fertile Al-Jazirah. The University of Damascus was established, with its teaching being mainly in Arabic.

It was more difficult to prepare Syria for self-government because of the difference between French and Syrian concepts of what was implied. Most French officials and statesmen thought in terms of a long period of control. Further, they did not wish to hand over power to the Muslim majority in a way that might persuade their Christian protégés that they were giving up France’s traditional policy of protecting the Christians of the Levant.

Druze Rebel Leader Sheikh Hilal al-Atrash, 1925

The first crisis in Franco-Syrian relations came in 1925 when a revolt in Jabal Al-Droze, sparked by local grievances, led to an alliance between the Druze rebels and the nationalists of Damascus, newly organized in the People’s Party. For a time the rebels controlled much of the countryside. In October 1925, bands entered the city of Damascus itself, and this led to a two-day bombardment by the French (see Druze revolt). The revolt did not subside completely until 1927, but even before the end of 1925, the French had started a policy of conciliation.

The administration of the region under the French was carried out through a number of different governments and territories, including the Syrian Federation (1922–24), the State of Syria (1924–30) and the Syrian Republic (1930–1958), as well as smaller states: the State of Greater Lebanon, the Alawite State, and Jabal Druze State. Hatay was annexed by Turkey in 1939. The French mandate lasted until 1943, when two independent countries emerged, Syria and Lebanon. French troops completely left Syria and Lebanon in 1946.

Sources: Encyclopedia Britannica Article; Wikipedia

|

Birmingham, Alabama, Doughboy Memorial

June 2020

|

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications

|

Order Our

WWI Musical CD

Click on Image for Information

|

Shop at

Amazon.com

|

Order the Complete Collection

Over the Top Magazine

Click on Image for Information

|

A World War One Film Classic

In 1932, A Farewell to Arms became the first Ernest Hemingway novel to make it to the silver screen. I read once that Hemingway disliked it as insufficiently pessimistic. Both my parents, who saw the film separately when it came out, thought it was a wonderful romance but not much of a war movie. Mom said, though, it was when she knew that Gary Cooper and Helen Hayes would both be big stars. The last time I viewed it, I found myself conceding that it is more a tragic love story than an exciting action tale. Yet, I still think it's a must-see for all World War One buffs. If nothing else, it helps in moving one's historical horizon beyond the Western Front. There WAS a big war going on in Italy at the same time.

Most likely our readers are familiar with the plot, which is set on the post-Caporetto Italian Front, along the Piave River where Hemingway himself was wounded. American ambulance section chief Lt. Frederic Henry (Cooper) encounters British nurse Catherine Barkley (Hayes) when he's drunk. Naturally, the first impressions are not good. However, fate intervenes. They meet up again on a blind date and the romance blossoms. It blossoms to the point that Catherine finds herself with child and is dispatched to distant Milan. Frederic, however, is subsequently wounded in action and finds himself cared for by Catherine at that very hospital in Milan. Complications and tragedy follow, but I'll leave it there.

Some notable attributes of the film are the Academy Award-winning cinematography, which was ground-breaking for the time (see the still above), and the well-played, heart-wrenching ending with both Cooper and Hayes at their dramatic best. Also deserving of a special mention is Adolph Menjou, who almost steals the early part of the movie as Frederic's cynical sometimes friend, sometimes manipulative supervisor Capt. Rinaldi. A Farewell to Arms is fairly easy to find. It's on Netflix as a DVD, Amazon Prime for streaming, and can even be found on some of those movie specialty networks that seem to be proliferating. By the way, the 1957 remake with Rock Hudson and Jennifer Jone has great mountain photography, but that's its sole merit.

|

|

Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

(Or send it to a friend)

(Or send it to a friend)

|

Design by Shannon Niel

Content © Michael E. Hanlon

|