July |

Access |

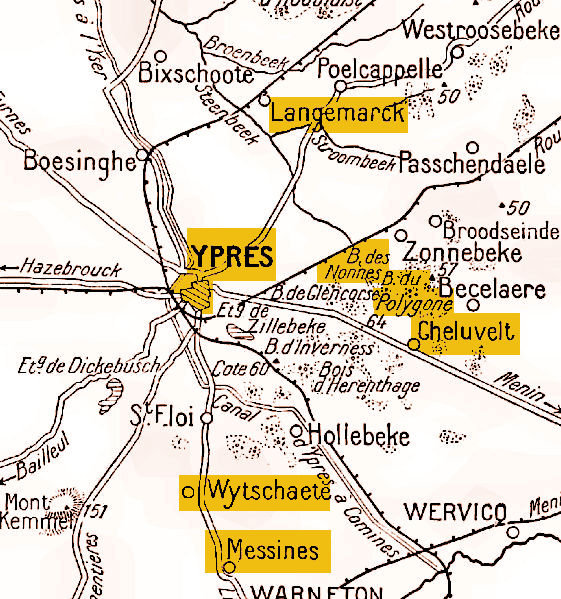

Belgium 1914

|

Different Perspectives

About the "Old Contemptibles" and "Student Battalions" that fought at Ypres in 1914:

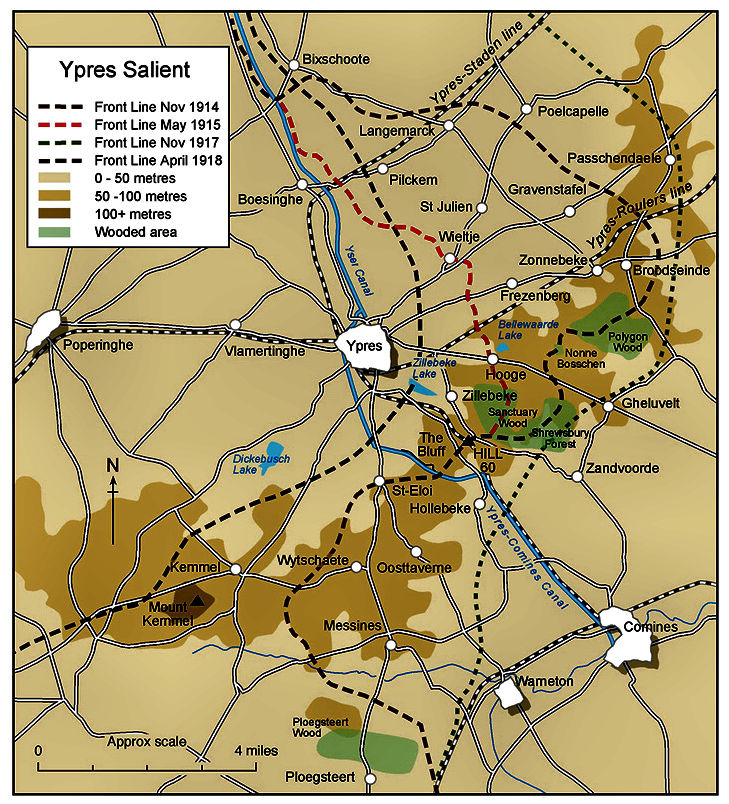

Ypres Salient, 1914-1918

|

|||||

Free Publications |

||

|

Amazon.com |

||

Black Watch Corner Memorial

One of the newer, but most dramatic on-site monuments to the 1914 fighting around Ypres, is the Black Watch Corner sculpture at the southwestern tip of Polygon Wood. Unveiled 100 years after the fighting it commemorates, the memorial, created by Edinburgh sculptor Alan Herriot, quickly became an essential photo-op for visitors to the battlefield. His work, showing a kilted Black Watch sergeant with a Lee-Enfield rifle and fixed bayonet, honors the 8,000 Scottish officers and soldiers from the regiment who were killed during the Great War. A further 20,000 were wounded between 1914 and 1918.

Near this position on 11 November 1914, men of the Black Watch (the Royal Highlander Regiment) and other Guards regiments stopped the last effective attack of the First Battle of Ypres. It had been mounted by the elite Prussian Imperial Guards Regiment.

Hitler's List Regiment at Ypres

Mourning German Soldiers

Langemark Cemetery

Then came a cold, wet night in Flanders and we marched through it in silence. When day began to break through the mist, we were suddenly met with an iron greeting as it hissed over our heads. With a sharp crack, it hurled the little pellets of shrapnel through our ranks, splashing up the wet soil. Before the little cloud was gone, the first “hurray” came from two hundred voices in response to this greeting by the Angel of Death. Then the crackling and thunder began; singing and howling, and with feverish eyes, everyone marched forward, faster and faster. At last, across beet fields and hedges, the battle began—the battle of man against man.

Adolph Hitler, Mein Kampf

Note: Hitler's inexperienced unit was part of the assault near Ghelhuvelt Chateau that commenced on 29 October 1914. He was not part of the "Student Battalions" that attacked near Langemark. Hitler did, however, visit the Langemark Cemetery on his June 1940 victory tour.

From a distance, the sound of song reached our ears, coming closer and closer, and jumping from company to company. Just as Death began to busy himself in our ranks, the song reached us too, and we in turn passed it on: “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles, über alles in der Welt!” (“Germany before all, Germany ahead of everything in the world”.) Four days later, we went back to camp. We even walked differently. Seventeen year-old boys now looked like men. Maybe the volunteers of the List Regiment (The Second Infantry Bavarian Regiment) had not really learned to fight, but they did know how to die like old soldiers.

The First Battle of Ypres: Langemark

21–24 October 1914

German Machine Gun Team

The battle of Langemark, 21-24 October 1914, north of the town, was part of the wider First Battle of Ypres. It began as an encounter battle between troops of the British I Corps and German troops of the Fourth Army, both probing for offensive opportunities. It ended with the Allies on the defensive around Ypres, holding off the first of a series of fierce German attacks that would be typical of the remaining battle for Ypres.

At the end of 20 October the two divisions of I Corps were separated. Sir John French—still unaware of the power heading towards Ypres—ordered the corps to gather near Langemark and then launch an attack to the north, with the overly ambitious aim of liberating Bruges. French believed that there was only one German army corps north of Ypres, when there were actually five between Ypres and the coast.

The start of the British attack was delayed by the time needed for the two divisions of I Corps to reach Langemark. After finally getting underwar, the advancing British began to encounter an increasing number of German troops, advancing to the attack from the north. At 1500 hrs. General Douglas Haig, commander of I Corps, cancelled his advance and ordered his men to hold their positions. The new front line was only 1,000 yards beyond Langemark. At the end of 21 October, the Allies finally realized that the Germans were present in much more strength than expected. Any idea of an offensive by the BEF was abandoned for the moment, and Foch, senior French general in the north, agreed to send the French IX Corps to Ypres.

The fighting on 21 October had left the 1st Division of I Corps badly stretched out west of Langemark. On 22 October, the Germans launched an attack along a large stretch of the British line, against the 1st, 2nd and 7th Divisions. The German attack was repulsed along most of the British line, apart from in the centre of the 1st Division. Here the 1st Battalion of the Cameron Highlanders held a semi-circular position north of the Kortekeer Cabaret. The line British line consisted of a series of unconnected trenches and rifle pits. Late in the afternoon, the Germans penetrated the northwest portion of the line. Once inside the semi-circle, they were then in a position to attack the remaining British positions from behind. At 1800 hrs, the Camerons were forced to retreat a quarter of a mile, leaving a potential gap in the British lines.

Haig responded to this crisis with a certain amount of flexibility, creating a reserve force from a variety of units. On the morning of 23 October, that scratch force recaptured the cabaret. At the same time a broader German attack against Langemark village to the east was defeated. Both battles were over by 1300 hrs.

Wounded German Soldier at Langemark

The same day also saw a French counterattack, launched by the 17th Division of IX Corps. The attack was launched from the front held by the 2nd Division. Foch had hoped for British support during his offensive, but his request didn’t reach General Haig until 0200 on 23 October, only seven hours before the attack was expected to begin. The French attack itself failed, but the French division replaced the British 2nd Division in the front line. The next day the 1st Division was also relieved, this time by two French territorial brigades. Often forgotten in summaries of the battle that focus on the bravery of the Old Contemptibles of the British Army, it was the French reinforcements who finally stabilized the line in front of Langemark.

An action at Langemark in the later stages of First Ypres added much to the mythic heritage of the war. The German reserve units attacked the well-ensconced positions of the enemy between Bixschote and Noordschote over open terrain on 10 November 1914 and suffered heavy losses. More than 10,000 German soldiers were wounded or killed in a battle that had no military significance. To conceal the disaster on the Western Front, the OHL published a famous official communiqué on 11 November 1914, which announced misleadingly that: "Westwards Langemarck young regiments rushed forward under the song 'Deutschland, Deutschland über alles', advancing against the first line of the enemy and taking it." The losses of these "Student Battalions" came to symbolize German heroism, patriotism, and a spirit of sacrifice, accentuated in the increasingly embellished accounts of how German troops had assaulted English machine guns without cover.

Sources: "Battle of Langemark," History of War Website; 1914-1918 Online

The First Battle of Ypres:

Down the Menin Road

19 October – 22 November 1914

At three dates during the larger battle, the tide of victory turned on actions at three locations near where the extreme eastern boundary of the salient crossed the Menin Road: Polygon Wood, Gheluvelt Chateau, and Nonne Bosschen. Here we will focus on these key struggles in their chronological order.

Some of the Old Contemptibles Fighting at Ypres in 1914

All battles are important, certainly to those who fought them. Moreover, the first battle in Polygon Wood was noteworthy as another of those fleeting opportunities for the Germans to push through a weak spot in the Allied forces, which they failed to exploit. Polygon Wood was on the northern side of the salient held by the British. On the morning of 24 October, the German XXVII Reserve Corps launched an attack to reduce the salient using four regiments of their 54th Reserve Division, supported by artillery, attacking the British 21st Brigade. The line south of Zonnebeke had been thinned due to movement of units of the 2nd Division to support a French counterattack to the west. This left just the 21st Brigade to defend Polygon Wood, five miles due east of Ypres and a few hundred yards south of Zonnebeke, and the only geographical barrier to a German assault on Ypres itself.

The grounds of Gheluvelt Chateau was where the war of movement on the Western Front stopped. Afterward, there would be no big breakthroughs until 1918, and 41 months of trench warfare would ensue. Launched at 0530 on 29 October, the German's big push would fall on the Gheluvelt crossroads which was located at the junction between the British 1st and 7th Divisions. Covered by fog, the German attackers advanced aggressively, taking many captives. As at Polygon Wood earlier, they did not seem to understand the opportunity presented to them. In any case, their capture of the crossroads gave them an excellent staging point for further attacks and an observation post for their artillery. The German commander planned to renew the attack the next morning, shifting the axis of attack south of the Menin Road. The 30th ended with progress in the south, Messines Ridge would fall in a day or two, and with the defending British line thinned out. The next morning, 31 October, the attack shifted back to the north with German artillery pounding the British 1st Division dug in just west of the village of Gheluvelt. With the utter destruction of the Second Welch Regiment, the road to Ypres and the Channel opened.

Polygon Wood

The two platoons forming the right of the Wiltshires defending the southern edge of Reutel were overwhelmed by attacks in their front, flank, and rear at about 0800. Germans in the village of Reutel, on the right flank and even behind the Wiltshires, attacked in force, while the rest of the Wiltshires were fully engaged at the front, and shot their way down the trenches from right to left, capturing what remained of the companies, the casualties exceeding 450 men. Brig. Gen. Watts, commanding the 21st Brigade, reported to the 7th Division headquarters the desperate straits of the Wiltshires and the 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers (who had already fallen back). The division commander immediately took from his cavalry reserve at Hooge the only unit available, the 1/1st Northumberland Hussars (known familiarly in the Army as "The Noodles") to check further enemy progress through Polygon Wood. Advancing dismounted, they stopped the Germans, who had paused—apparently unaware of the breakthrough they had made—long enough for the 2nd Warwicks, detached from the 22nd Brigade, to join them and this ad hoc force then drove the Germans back, suffering nearly 300 casualties, including the senior officer Lt. Col. W.L. Loring of the Warwicks.

The next day, with the Germans still holding the northern half of the wood, the 1st Irish Guards and the 2nd Grenadier Guards, from 4th Brigade, 2nd Division, were ordered to clear them out. The scene was later described as "a slaughterhouse." During the early hours of the 26th, these two battalions were reinforced by the 3rd Coldstream Guards, and all attacked again. However, the Germans held their ground and the action was over. Three days later, though, the German Army would be back in the area with their maximum effort of the First Battle of Ypres.

Gheluvelt Chateau

By mid-day on 31 October 1914, there were no more flanks, just one last gap in the entire line from the Swiss border to the English Channel where a breakthrough seemed possible. Shortly before noon the line of the British 1st Division was broken at Gheluvelt. If at that moment German reinforcements available close at hand could thrust through the gap and spread out fanwise, they could have rolled up the defenders on either flank in their rear and simply broken the cohesion of the British in Flanders to pieces. The impulse of retreat began to seize the British troops. Already men and guns were streaming back toward Ypres. The Germans quickly assembled 13 battalions for a final follow-through attack.

.

Gheluvelt Chateau Today

General Charles FitzClarence, commanding the British Army 1st Brigade, was riding nearby and saw the deteriorating situation. At Polygon Wood north of Gheluvelt, he found the 2nd Worcestershires, part of the reserve of the 2nd Division on the north, and ordered them to counterattack immediately. This movement had scarcely begun when a shell burst in Hooge Chateau, where the staff of both divisions had assembled for a conference, and practically destroyed them.

The German Army, though, had not quite given up on breaking through at Ypres. The Fourth Army was ordered to prepare another assault over a broad front. On 11 November, after an intense bombardment, their best advance was just north of the Menin Road. They captured Gheluvelt Chateau and they pushed almost a mile to Nonne Bosschen, a small wooded area next to Polygon Wood. Once again, however, counterattacks drove the Germans back. The most famous of these is commemorated with the painting shown at the very top of this issue. At 1400 hours, the 2nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, accompanied by a company of the Northamptonshire Regiment and the 5th Field Company, Royal Engineers who did not want to be left out of the action, moved forward to clear Nonne Boschen of the 1st Prussian Foot Guard.

But the Worcestershires — a tiny force of eight officers and 360 men — swept all before them nonetheless. They fell upon their adversaries, who were mostly Bavarians, and drove them back in confusion from the chateau grounds. The line was reestablished. The Western Front of the Great War was de facto completed. It would not move dramatically until the first Ludendorff Offensive of 1918. General FitzClarence, sadly, did not have much longer to live. He died in the last big action, on 11 November 1914 in fighting along the Menin Road, where many more would fall in the remaining four years of war.

Nonne Bosschen

After a final attack on 17 November, German forces moved into a defensive mode in the west and sent available troops to the Russian front. Sporadic fighting continued until 22 November, when the arrival of winter forced an end to the battle. The Allies claimed a victory. Yet, both sides had lost many of their finest soldiers. The generals had discovered modern industrial war was a man-eater. If ever there was a time to invoke diplomacy to bring the war to an end, this was it. But no one was ready for that. A month later, the Ypres battlefield would be the site of the most famous episode of the 1914 Christmas Truce.

100 Years Ago:

|

The Fallen at Hill 80 Now Rest in Peace

Burial Service at Langemark Cemetery

Over 800 people gathered on windy 11 October 2019 day at the Langemark cemetery to attend the ceremonial interment of the German soldiers discovered during the internationally funded Hill 80 archeological project. The dead were found during archaeological work at the former position "Hill 80" near Wytschcaete, five miles south of the town of Ypres. Starting in 2018, volunteer helpers under scientific supervision recovered 110 German, British, French, and South African dead bodies and documented their findings.

Earlier, the president of the Volksbund, Wolfgang Schneiderhan, together with the mayor of Langemark-Poelkapelle, Lieven Vanbelleghem, and the German ambassador to Belgium, Martin Kotthaus, laid wreaths in the communities of Langemark and Wytschcaete to commemorate the many victims of the villages killed in the Great War. In his greeting, the mayor thanked the Volksbund and summed up "... that the memories of that war were still powerful 100 years later".

Service at Wytschaete CWGC Cemetery

The previous day, a smaller crowd witnessed the burial service for the 13 deceased soldiers found at the Hill 80 site from Commonwealth nations including the UK, who were buried side by side at a ceremony at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s Wytschaete Military Cemetery.

A World War One Documentary

This 47-minute presentation is one of the six episodes presented by ITV on British television in 2005 collectively named The Great Battles of the Great War. I've seen a number of Gallipoli presentations in the past and this is broader in its scope than any I've encountered. For instance, it begins at nearby Troy explaining why the straits have been so important historically. Then, it gives a detailed discussion of how Turkey managed to decide to join the Central Powers. From this base of knowledge, it describes the naval and land campaigns as they unfolded and successively failed for the Allies. My only disappointment is that the producers did not point out what I've concluded after my own visits to Gallipoli—that the whole expedition was ill conceived, doomed to failure, and beyond the operational capabilities of the invaders at the time. Nevertheless, it's an excellent introduction to one of the most famous military events of the 20th Century. Almost forgot—it uses present-day camera work in conjunction with historic photos to show just how large the Gallipoli Peninsula is and how disconnected the various forces at Cape Helles, Anzac, and Suvla Bay turned out after each landing got bogged down.

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon