August |

Access |

The Mutilated and Shell-Shocked Come Home to America

Amputees from Walter Reed Hospital on an Excursion to the Seashore

Not Forgetting 1914–1918

I recently ran across an old (2011) editorial from another publication about my approach to presenting material on the Great War. Since it applies equally to all I'm trying to do on Worldwar1.com's publications, I thought I might share it with our Trip-Wire readers with a few updates and revisions.

Panthéon de la Guerre (Detail), U.S. National World War I Museum, Kansas City

I am sure a number of you have shared my experience of being told by acquaintances that studying the First World War seems pointless, irrelevant, and (I really hate this one) that it must be "So Boring!" We all

deal with these comments in our own way and we "soldier on." Recently, though, an even more curious reaction sometimes comes in my contacts with more highly educated types (degrees in multiple numbers and/or from "elite" colleges). In their view, if I'm interpreting it correctly, the war was so awful that it belongs in a special intellectual category: unworthy of consideration, not to be spoken of, stricken from the collective memory of mankind. On my gloomier days, I've begun to fear that our "best and brightest" in some post-modern suicide pact are rejecting our heritage–disregarding Justice Holmes's caution that continuity with the past is a necessity. More recently, I've found the overall response by Americans to both the Civil War Sesquicentennial and the World War One Centennial quite underwhelming. [Those of you who were around for the 1961–1965 Civil War Centennial will probably understand what I mean.]

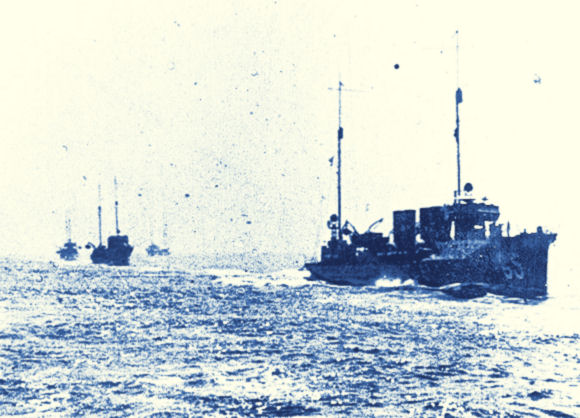

"The Return of the Mayflower"

|

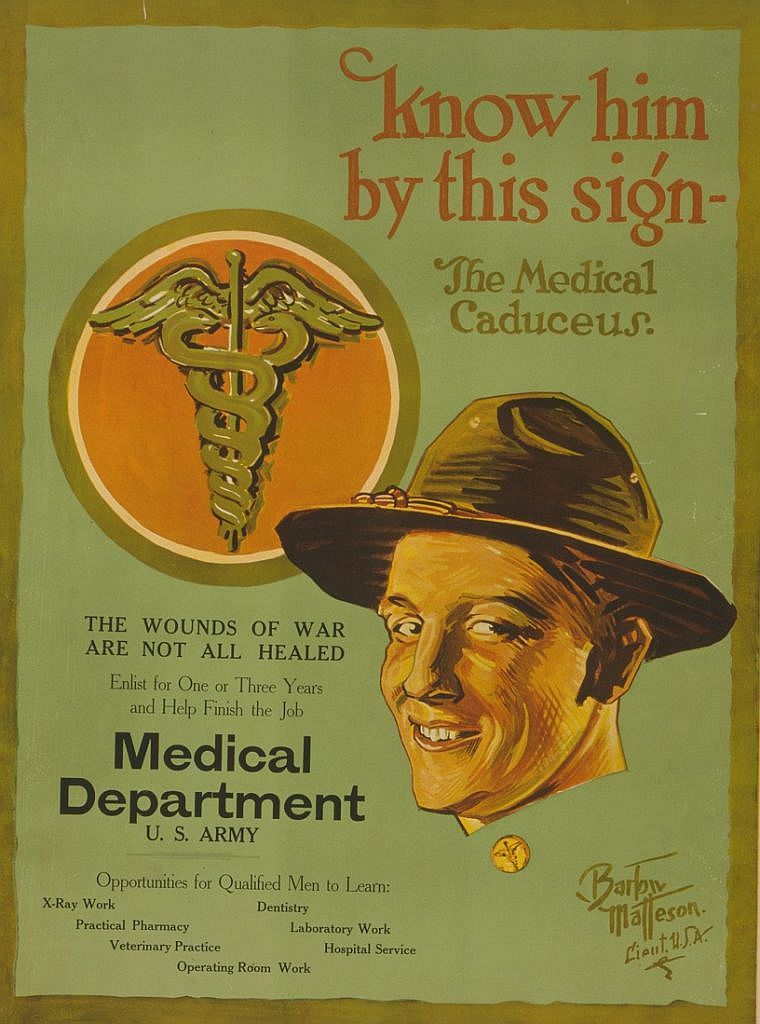

Disabled Doughboys

The Great War never ended for the men of the AEF who found themselves permanently scarred physically or psychologically by the war. The Library of Congress provides some shocking figures. About 148,000 patients had to be transferred to hospitals back in America through the end of 1919 for additional or long-term care. Eventually 200,000 veterans would be granted permanent disability status. Adding together all the categories of injury, such as respiratory problems from gassing, facial disfigurement, amputations (a surprisingly low figure of 4,900 cases), neuropsychiatric issues, and allowing for those who just refused to seek care, researchers estimate that about 300,000 of the returning Doughboys lived the rest of their lives with serious damage from the war. And, tragically, many of these men also died early deaths.

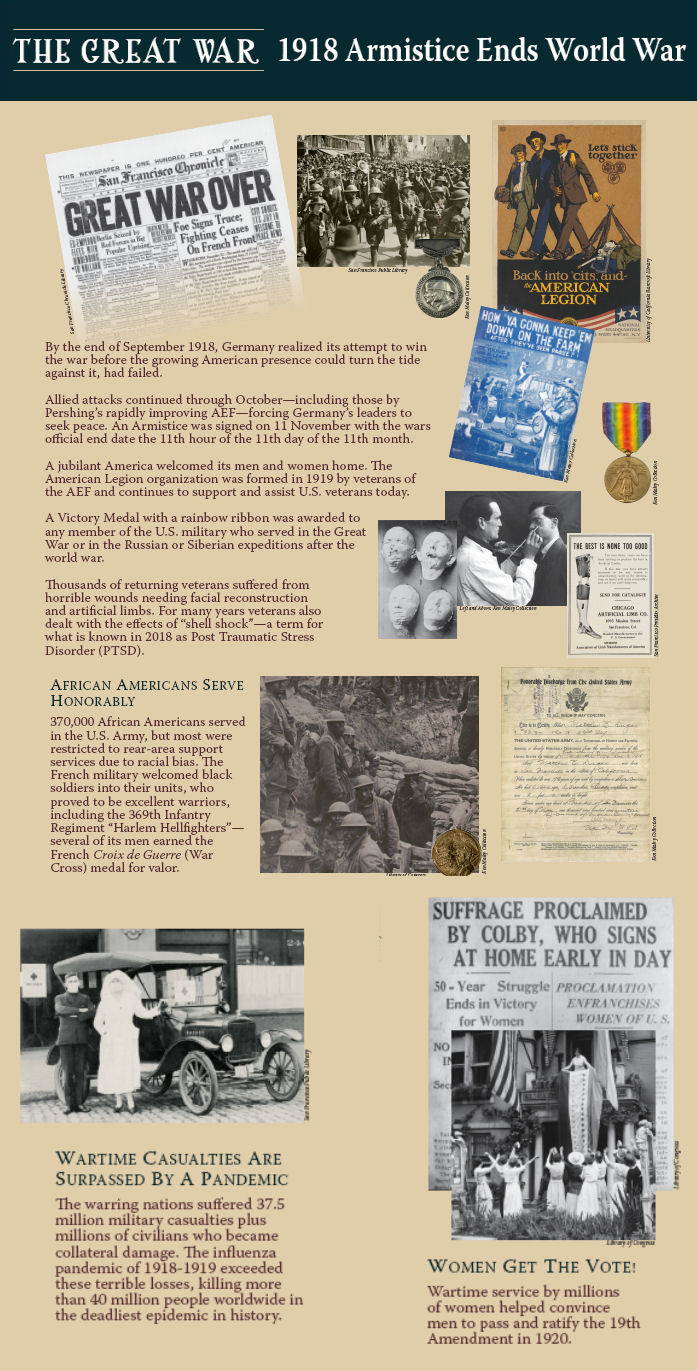

Rehabilitation vs. the Pension System

Opposed to the perceived economic inefficiencies and political corruption of the pension system, Progressive Era reformers encouraged the Wilson administration to institute programs in rehabilitation, providing injured soldiers with long-term medical care and vocational training in order to drastically reduce–and potentially–erase cash payments made out to veterans. . . Progressive reformers believed that the government could (and should) "rebuild war cripples," curing them of their disabilities. . . Men returning home with amputated arms and legs were to be "refitted," not only with prosthetic limbs, but also to an appropriate workplace, so that, as one rehabilitation advocate put it, a soldier's disability would not be a "handicap."

Recuperating Doughboys in London

|

|||||||

Looking Back: A Retrospective of the War | ||||||||

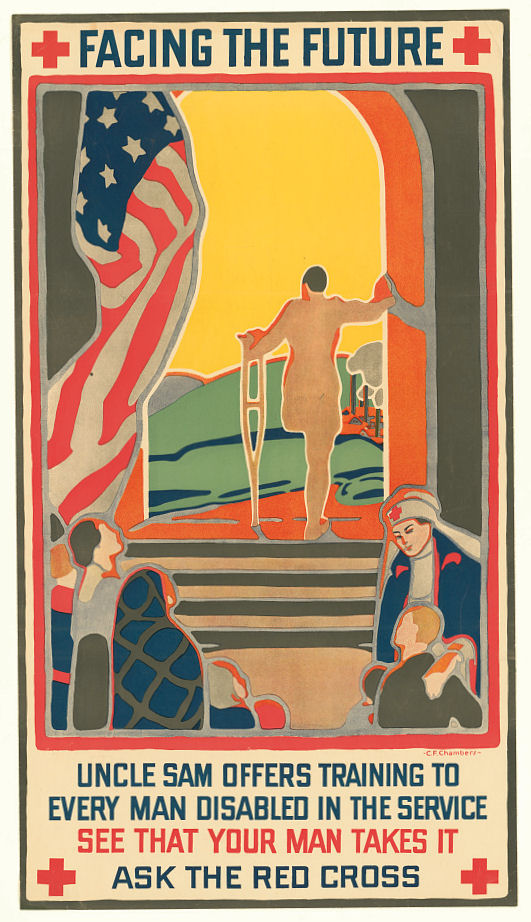

Sgt. Roy Thompson |

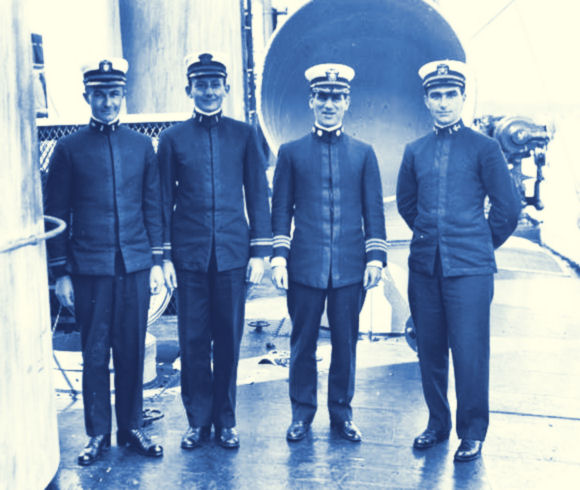

Future Doughboy Roy Thompson grew up on a farm outside Albion, Washington. As a teenager he found neither farming nor schoolwork appealing, leaving high school far short of graduation. He loved to fix things, however, and his inclinations soon led him to working on farm machinery in a local garage, and he found employment operating a massive wheat thresher. He came to realize, though, that there were some useful things to absorb in school for a budding mechanic, such as algebra. Roy spent late 1916 and early 1917 back in high school. Then—surprise—Uncle Sam came knocking. America needed lots of soldiers immediately, if not sooner. He was drafted and inducted into the Army at Fort Lewis, Washington on 4 November 1917. By some magical personnel processing, the Army actually discovered that Roy would be more valuable to the war effort as a mechanic than an infantryman and trained him accordingly. By February 1918 he was aboard the USS President Lincoln heading for France with the other men of the 1st Motor Mechanics Regiment. Roy wrote many letters home to the "Dear Homefolks" and kept a diary, well documenting his service time. An early letter he wrote from his troopship on 13 February suggests he was better suited for the army than the navy.

Dear Homefolks:

Well, I'm out in the middle of the big water, and still able to handle my meals as usual. I think this fact is due to the good weather, as we have only had one day that was very rough. I have been feeling somewhat shaky, and have had a headache a good deal, but haven't been disabled yet.

At the time he wrote this letter, Roy obviously had sensed no omen that he was sailing on a doomed ship–on 31 May 1918 the President Lincoln was torpedoed by German submarine U-90 and sunk about 500 miles off the French coast on a return trip to the U.S.–nor that, within a year, he would be "disabled" for the rest of his life.

Roy was soon assigned to the Air Service as a mechanic and spent the duration of the war at shops and depots in the eastern part of France, behind the huge American battlefields in the vicinity of Verdun. His duty, he reports, was away from the shooting war, involving long hours doing the typical work of mechanic (mostly automotive) with some construction thrown in:

Sat. 8 June

Putting up track in boiler shop and lining up the A-beams thereof.

Weds. 12 June

Went to work at 7 am overhauling Studebaker. Quit at 10 pm.

Mon. 12 August

Working on a Benz (German). Took in French lesson at the Y but didn't learn a great deal.

So the diaries continue on, through the great St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne Offensives, the Armistice, and the winding-down right up until January 1919, when Roy's life would take a terrible turn. An unlucky accident would set him off on a medical odyssey to seven military hospitals, where multiple amputations took his right foot and then additional sections of his right leg as infection spread. At the final stop, Letterman General Hospital at San Francisco's Presidio, he had the good fortune to be treated at the very place a groundbreaking new type of artificial limb was being developed, the "Letterman Leg."

An Orthopedics Ward at Letterman General Hospital

The chain of events started when he was granted leave in January 1919 and started out on bicycle with a buddy heading for the town of Abainville where other Air Service shops were located. Attempting to jump a passing train, he had some unspecified mishap and badly injured his right foot. While his letters to his family at the time consistently understated the seriousness of his wound, he was much more candid in his diary:

Sun. 5 January

Griner and I started to Abainville on bicycles. Train accident at 2:10. Taken to Gondrecourt hospital and immediate operation.

Mon. 6 January

Lots of pain. Morphine before I could sleep

Tues. 7 January

More pain. Wound dressed A.M. Foot amputated about 3 pm. Lots of pain after I came out of ether. Finally morphine and some sleep.

Several hospital stops and operations later, after seven weeks, Roy was pleased with his progress:

Weds. 27 February

Wound entirely healed. . .

Three weeks later at the AEF hospital at Beau Desert, France, he received his first artificial leg. It didn't fit very well, and this led to a blister and another infection. But these problems were apparently treated sufficiently to allow Roy to head home. He departed France aboard the USS President Grant on 24 April and arrived in Hoboken, New Jersey, on 6 May. He spent over a month getting checked out at Army General Hospital #3 at Rahway, New Jersey, before being assigned to Letterman General Hospital located in what Roy called "Frisco." He arrived at the Presidio on 12 June. Two weeks later he was measured for his "Letterman Leg." In his diary, Roy doesn't indicate exactly when he was issued this new leg, but he was granted an extended furlough in the latter half of 1919, returning to Letterman in January 1920, when he received his full discharge. Roy Evans Thompson, disabled vet, was now a civilian. But, he intended to be a fully productive citizen and began immediately to build his skill set.

Roy and His Mother Cora at His Graduation from Washington State College, June 1925

After his discharge, he immediately enrolled and attended a one-year accelerated high school program to prepare him for Washington State College in Pullman. In a class paper he wrote about his revised views of education:

My experiences have brot [sic] about some very decided changes in my opinion of educations. From complete satisfaction over an eighth grade diploma to a great desire for all the education I can get is a considerable reversal of sentiment. I am indeed thankful that I was shown the advantages of education before all opportunity of acquiring one was gone.

By 1921 he had completed his high school work in the specialized college preparatory program and enrolled in Washington State, pursuing two degrees, a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering and a Bachelor of Arts in Education. He received both degrees in June of 1925. Sometime before graduation Roy also became a landowner. He filed for a homestead in Okanogan County, Washington, lived on it for six months to obtain title, and then rented out the land to a local farmer. When he graduated, he left the state to pursue his career as a mechanical engineer.

From 1925 Roy worked as a professional engineer. His first position was with the United States Patent Office in Washington, DC. He left after a year and worked for a series of manufacturing companies across America for over 40 years. He specialized in the design of gears and power transmission equipment and was granted at least two patents for his inventions. Roy had married Hester McCracken at the start of his career in 1925. They had two children, Dale and Marjorie, and four grandchildren. Roy retired in 1968 and lived ten more years, during which the former high school drop-out and Doughboy became a dedicated booster of continuing education.

Roy's son, Dale Thompson, has compiled all his father's war letters, diary, documents, and photos, along with considerable biographical commentary on his dad in a 206-page book titled Dear Home-folks. (Cover shown on right.) If you would like an autographed copy email Dale at: DALE.THOMP2@GMAIL.COM. The price is $12.00 plus mailing.

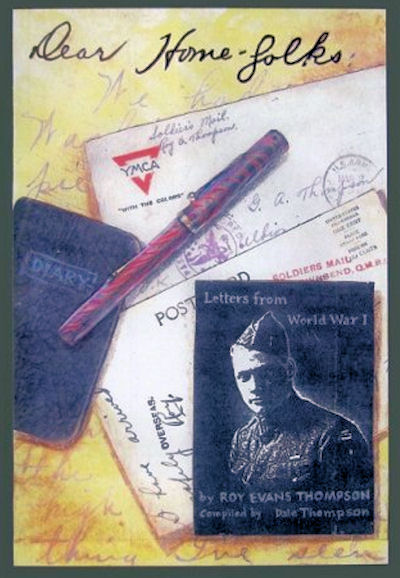

A Red Cross Nurse's Vision

William Allen Rogers (1854–1931). "Red Cross Nurse Seeing Vision of Wounded Soldiers Across Stormy Sea," (Detail) Library of Congress Collection

100 Years Ago:

|

General Denikin |

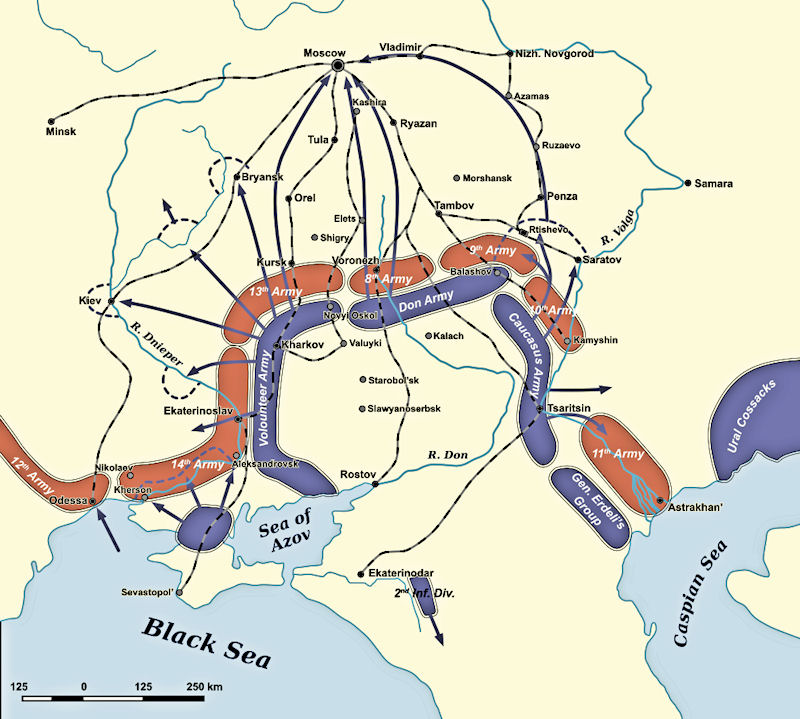

While Denikin’s armies advanced throughout August and September, the Red Army bitterly disputed the direction of its counterblow, much of it driven by inter-party politics. Vacietis was replaced as Red Army supreme commander by Sergei Kamenev, who organized counterattacks in the directions of Tsaritsyn and Kharkov in an effort to cut off Denikin from his base. After two months of heavy fighting, Red forces were stymied and beaten back.

The Advance as Planned

Denikin, on the other hand, continued to advance into Ukraine and southern Russia, entering the Reds’ weakened center on Moscow, and taking in succession Poltava, Odessa, Kiev, Kursk, and Voronezh. By mid-October Denikin’s troops had reached Oryol, roughly 240 miles south of Moscow, essentially the closest he

would come to his goal, but he also stretched 700 miles from his base of operations in the Kuban. At that point,

Red Army Headquarters admitted its error and rushed Trotsky to take command of the southern front.

Although the White Army successfully drove back the communists, its campaign into Ukraine incited much

confusion and misery, which included violent pogroms inflicted on the Jews, especially by Cossacks, who also engaged in looting. Ukraine was further beset by anarchy, partisan activity, local uprisings, and the beginnings of the Bolshevik Red Terror in the provinces

General Denkin’s offensive lost steam as his front widened. The distance between him and his forces incurred a loss of control and direction, which contributed to depredations committed by his troops and the alienation of the

peasant majority. Furthermore, troops in the field lacked supplies, as well as reinforcements. Equally important, he refused even to consider Ukrainian independence, thus depriving his cause of a potential ally.

As Denikin’s forces were turned back in mid-October, a smaller North-Western White Army under the command of General Nikolai Yudenich advanced from Estonia into Russia, stopping just 15 miles from a beleaguered Petrograd.

Alexander Yegorov, Commander

Red Southern Front

Following the defeat and retreat of White forces in autumn 1919 and winter 1920, an oppositional group of generals under Petr Nikolaevich Wrangel (1878-1928) developed. The military council of Feodosia in March 1920 chose Wrangel as the new commander-in-chief. Denikin confirmed this decision and went into retirement.

The general took his family to Constantinople and then London. In August 1920, he moved to Brussels and in June 1922 to Budapest. After that, he returned to Belgium in 1925, later settling in a suburb of Paris in 1926. He did not take an active role in the political and social life of the Russian emigration, concentrating instead on writing. During the German occupation of France, from 1940 to 1944, he lived in Moussan, in the south of the country and refused to cooperate with the German authorities. He came out in support of the Red Army in the Second World War and against the Russian All-Military Union, which was in favour of working with Nazi Germany. In November 1945, he emigrated to the USA, where he lived for more than two years. He was first buried in Detroit, but, in December 1952, was reinterred in the St. Vladimir Orthodox cemetery in Jackson, New Jersey. In October 2005, the Russian government had the remains of Denikin and his wife transferred to his homeland, where they were reburied in the Donskoi Monastery in Moscow.

Sources: Sources: Library of Congress, Wikipedia, and 1914-1918 Online

One of the more creative memorials to be dedicated during the recent WWI Centennial is spread across the dunes along the North Sea near Thyorøn, at the very tip of Denmark's Jutland Peninsula. Twenty-five granite stones shaped as ship bows represent every ship sunk in the 1916 Battle of Jutland, which was fought about 100 km. offshore. They are surrounded by human figures showing a proportional representation of the 8,645 seamen who perished in the battle.

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications |

||

Order Our

|

Shop at |

Order the Complete Collection

|

A World War One Film Classic

Visually, The Blue Max flies higher than almost any WWI aviation flick ever produced. Its aerial sequences are enthralling, as is the introductory trench warfare episode. The ambitious, medal-chasing central character, infantryman turned aviator Bruno Stachel (played by George Peppard), proves abrasively fascinating in every scene where he appears. The author of the original 1964 novel, Jack D. Hunter, found Bruno so magnetic he resurrected him for his readers for two sequels in the 1970s and '80s that are excellent reads. Also, under the visual category, a big asset is the casting of in-her-prime-gorgeous Ursula Andress as the love interest.

The only shortcomings (for me) involved some characterizations of the principals with respect to the novel. The ruthlessness of former corporal Stachel and the matching seething disdain radiating from his aristocratic rivals are watered down unnecessarily. I was also annoyed that Bruno's mentor was stripped of the pornography collection that made him interesting and added a little humor to the original story. Finally, there's a contrast that I found distracting due to the mixed nationalities (British, U.S., German) of the cast. The Yanks and Brits playing Germans (including the great James Mason) just don't project as Germanic as their compatriots. Consequently, the German Air Service seems more broadly multicultural than the collection of Prussians, Bavarians, and Saxons it was. Nevertheless, this is just the usual stuff from Movieland and shouldn't deter any aviation, history, or high adventure buffs from watching The Blue Max. The film is available on Netflix and for purchase on Amazon.

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon