August |

Access |

Medal of Honor Recipients

Medal of Honor Ceremony at Chaumont GHQ, 7 February 1919

|

||||||||

|

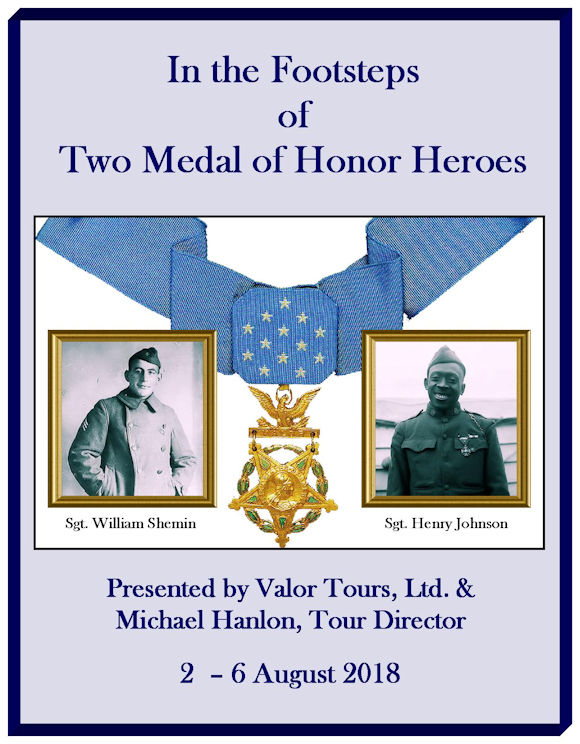

Two years later, I was contacted by Elsie Shemin, daughter of Sgt. Shemin, and was told I had been recommended to her as someone who could organize a tour to the sites where both the recipients had served in France and had fought their most memorable actions. The tour participants would be members of the Shemin family and a representative of the Henry Johnson family, who turned out to be a soldier from the successor unit of the 369th, which is now part of the 42nd Rainbow Division.

The trip (cover of the trip book on left) turned out to be one of the most enjoyable I've ever conducted. One thing I learned from this experience–thanks to Elsie's collection of files–was that the services conduct a tremendous amount of research to ensure that the award of the Medal of Honor is fully justified and that there's much more to the story than the terse citations that are usually used in articles to describe the individual's achievements. So, for this issue, I've searched for material that gives some broader information about a representative selection of Medal of Honor recipients, their lives, and their memorable achievements. I hope you enjoy what I've put together. MH

Recipients: Lieutenants Harold E. Goettler & Erwin R. Bleckley (KIA),

50th Aero Squadron

By Steve Ruffin

Airdrop to the Lost Battalion by Merv Corning, depicting Goettler and Bleckley's first of two missions they flew on 6 October 1918. (Courtesy Esterline Power Systems' LEACH Heritage of the Air Collection)

A total of 121 American servicemen earned the Medal of Honor for actions performed in World War I. Military aviators–the Great War's newest breed of military hero–earned eight of these. Four went to men of the Army Air Service and two each to Navy and Marine Corps airmen.

Of these elite eight, two were famed Army Air Service fighter aces. Both are still widely remembered today. Captain Edward V. Rickenbacker was America's "Ace of Aces," with 26 victories, and the commander of the 94th "Hat in the Ring" Aero Squadron. Lieutenant Frank Luke, Jr., was the 27th Aero Squadron's flamboyant "Arizona Balloon Buster" who downed a record-breaking 18 German aircraft in as many days in September 1918.

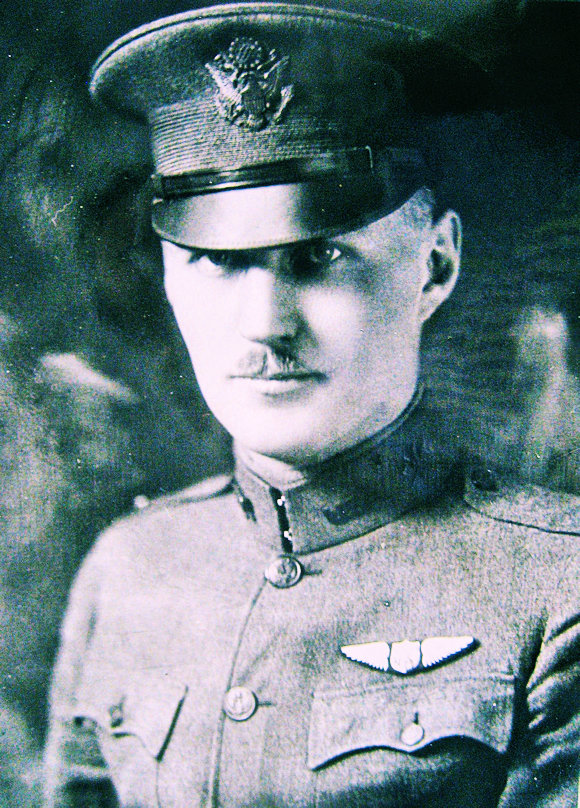

Lieutenant Goettler

The two lesser-known Army Air Service Medal of Honor recipients are Lieutenants Harold E. Goettler and Erwin R. Bleckley. They were a pilot/observer team, flying the De Havilland DH-4 "Liberty Plane" for the 50th Aero Squadron. Goettler was a Chicago native and former University of Chicago football star, while Bleckley, who manned the back seat as gunner/observer, hailed from Wichita, Kansas. The two men lost their lives earning the coveted Medal on 6 October 1918, while trying to aid the men of the ill-fated "Lost Battalion."

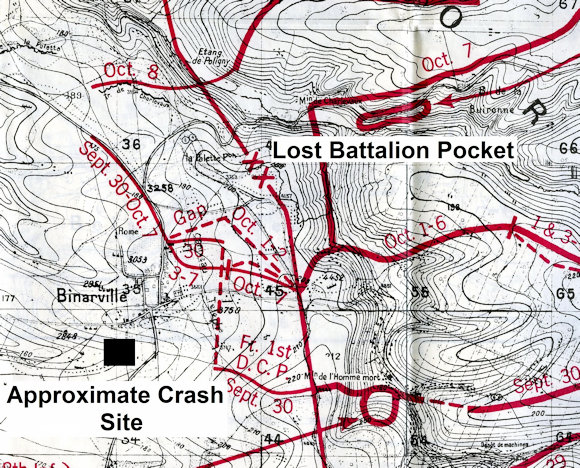

This group of some 700 American 77th Division soldiers, commanded by Major Charles W. Whittlesey, had advanced through the Argonne Forest ahead of their left and right flanks. When they reached a steep tree-covered ravine northeast of the town of Binarville, enemy troops slipped behind and surrounded them. They were running critically short of food, ammunition, and medical supplies while being decimated by deadly gunfire coming from all directions. The 50th Aero, an aerial observation squadron operating in the vicinity, was immediately called on to deliver provisions to the beleaguered men.

Aircrew after aircrew flew over the presumed location of the trapped Doughboys, dropping bags filled with everything from chocolate and bandages to ammunition and carrier pigeons. While doing so, they took heavy, concentrated ground fire from the ring of enemy guns below. But since the Americans crouching in the underbrush were unable or unwilling to display their location panels, most of the precious supplies fell into German hands.

Late on the afternoon of 6 October, Lieutenants Goettler and Bleckley volunteered for their second mission of the day over the deadly ravine. They knew firsthand how hazardous it was, having already experienced the withering enemy gunfire. They also knew that four of their squadron mates had failed to return that day. However, they were resolved to locate and supply the encircled Americans.

Ground observers watched in awe as the two daring airmen methodically flew over the deadly ravine and through the murderous gauntlet of German gunfire concentrated on them. Completely disregarding the danger, they flew through it low and slow–not once but several times. It was the only way to pinpoint the position of the entrapped men whose lives depended on the goods the airmen were carrying.

Lieutenant Bleckley

Inevitably, luck ran out when a German machine gun bullet hit and instantly killed Goettler. Moments later, the big Liberty DH-4 dove into a field just inside French lines and crashed, fatally injuring Bleckley as well.

The two airmen were posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for their heroic actions. In 1922, the War Department awarded them the Medal of Honor "for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty. . ."

Goettler and Bleckley's initial burial site, near the American Red Cross Hospital No. 110 at Daucourt. Note the identification disks nailed onto the wooden crosses. (NMUSAF)

Goettler and Bleckley may lack the name recognition of Rickenbacker and Luke, but the raw courage they displayed while attempting to save their fellow soldiers was second to none. Their sacrifice will never be forgotten.

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

Different Perspectives

Here are some sites with details about Medal of Honor Awards and remembrances of other recipients.

![]() History of the Medal of Honor

History of the Medal of Honor

![]() Standards for the Award of the Medal of Honor

Standards for the Award of the Medal of Honor

![]() Design of the Medal of Honor

Design of the Medal of Honor

![]() Benefits for Medal of Honor Recipients

Benefits for Medal of Honor Recipients

![]() WWI Medal of Honor Citations

WWI Medal of Honor Citations

![]() WWI Air Service Medals of Honor (Video)

WWI Air Service Medals of Honor (Video)

![]() Pershing's 100

Pershing's 100

![]() Lt. Edouard Izac, USN, MOH

Lt. Edouard Izac, USN, MOH

![]() Frank Luke's Last Mission (Video)

Frank Luke's Last Mission (Video)

![]() The Sgt. York Discovery Trail

The Sgt. York Discovery Trail

![]() Sgt. Alan L. Eggers, 27th Division

Sgt. Alan L. Eggers, 27th Division

Raindrops on Your Old Tin Hat

There's a whispering of wind across the flat,

You'd be feeling kind of lonesome if it wasn't for one thing

The patter of the raindrops on your old tin hat.

An' you just can't help a-figuring—sitting there alone—

About this war and hero stuff and that,

And you wonder if they haven't sort of got things twisted up,

While the rain keeps up its patter on your old tin hat.

When you step off with the outfit to do your little bit,

You're simply doing what you're s'posed to do—

And you don't take time to figure what you gain or lose—

It's the spirit of the game that brings you through.

But back at home she's waiting, writing cheerful little notes,

And every night she offers up a prayer,

And just keeps on a-hoping that her soldier boy is safe—

The Mother of the boy who's over there.

And, fellows, she's the hero of this great, big ugly war,

And her prayer is on the wind across the flat,

And don't you reckon it's her tears, and not the rain,

That's keeping up the patter on your old tin hat?

Commentary by Connie Ruzich

Written by Lt. J. Hunter Wickersham of the 89th Division the night before the St. Mihiel Offensive began. The next day, after being severely wounded by artillery fire, he continued leading his platoon despite a great loss of blood. He eventually died on the battlefield and received the Medal of Honor posthumously.

WWI Medal of Honor Awards

One hundred twenty-six Medals of Honor were awarded to 121 United States soldiers for actions performed during World War I. Of those recipients, 34 of whom received the Medal posthumously, 92 served in the Army, 21 served in the Navy, and eight served in the Marine Corps. In addition, Congress awarded six Medals of Honor to unknown, unidentified soldiers of Belgium, France, Great Britain, Italy, Rumania, and the United States to pay tribute to each country’s unknown dead.

At the time, Army and Army Air Service soldiers received the Army Medal of Honor and Navy, and Marine Corps soldiers received the Navy Medal of Honor. Despite this distinction, five marines received both the Army Medal and the Navy Medal for actions performed while their Marine units were under Army command. To prevent future double recipients, Congress amended the criteria for receiving the Medal of Honor in 1919 to limit soldiers to one Medal.

Congress authorized the Medal of Honor to three deceased World War I veterans over 70 years after their service. Freddie Stowers received the Medal of Honor in 1991, and Henry Johnson and William Shemin received the Medal of Honor in 2015.

Source: The Pritzger Museum

Recipient Alvin York: After Action

8 October 1918: So when I got back to my major's p.c. I had 132 prisoners. We marched those German prisoners on back into the American lines to the battalion p.c. (post of command), and there we came to the Intelligence Department. Lieutenant Woods came out and counted 132 prisoners. And when he counted them he said, "York, have you captured the whole German army?" And I told him I had a tolerable few.

We were ordered to take them out to regimental headquarters at Chatel-Chehery, and from there all the way back to division headquarters, and turn them over to the military police. On the way back we were constantly under heavy shell fire and I had to double time them to get them through safely.

There was nothing to be gained by having any more of them wounded or killed. They had surrendered to me, and it was up to me to look after them. And so I done it.

I had orders to report to Brigadier General Lindsey, and he said to me, "Well, York, I hear you have captured the whole #$&@^@ German army." And I told him I only had 132.

After a short talk he sent us to some artillery kitchens, where we had a good warm meal. And it sure felt good. Then we rejoined our outfits and with them fought through to our objective, the Decauville Railroad.

And the Lost Battalion was able to come out that night. We cut the Germans off from their supplies when we cut that old railroad, and they withdrew and backed up.

So you can see here in this case of mine where God helped me out. I had been living for God and working in the church some time before I come to the army. So I am a witness to the fact that God did help me out of that hard battle; for the bushes were shot up all around me and I never got a scratch.

So you can see that God will be with you if you will only trust Him; and I say that He did save me. Now, He will save you if you will only trust Him.

Source: Alvin York's Diary, Sgt. York Patriotic Foundation

Recipient: Corporal John H. Pruitt, 6th Marines, 2nd Division (KIA)

John Henry Pruitt was born on 4 October 1896, in Fallsville, Arkansas. He entered military service from Phoenix, Arizona, in May 1917. He enlisted as a private in the U.S. Marine Corps on 3 May 1917 and joined the 6th Regiment of Marines in July 1917. He went overseas with the 78th Company, 6th Regiment.

Corporal Pruitt

He participated in engagements with the enemy at Chateau-Thierry, Bouresches, and Belleau Wood before he was gassed on 14 June 1918 and sent to a base hospital. Upon his recovery, he returned to the front and fought in the Marbache Sector, St. Mihiel, Thiaucourt, and later at Blanc Mont in the Champagne Sector. He was officially cited for bravery in action, near Thiaucourt, France, 15 September 1918, for aiding in the capture of an enemy machine gun.

At Blanc Mont Ridge on 3 October 1918, Pruitt single-handedly attacked two machine guns, destroying them and killing two of the enemy. He then captured 40 prisoners in a dugout nearby. This gallant Marine was killed the next day by shell fire while he was sniping at the enemy. It was his 22nd birthday.

John Henry Pruitt's remains were returned to the United States and buried at Arlington National Cemetery. The United States Navy named a destroyer USS Pruitt (DD-347) in his honor in 1920. Pruitt Hall on Marine Corps Base Quantico is named for him.

Sources: Marine Corps University; Wikipedia

Recipient: Private Nels Wold, 138th Infantry, 35th Division (KIA)

Winger, Minnesota

Nels Wold was born in Winger, Minnesota, in 1895 to parents who had emigrated from Norway. He was one of ten siblings. As a teen, Wold worked a few jobs before joining the Army in April 1918. Shortly after that, his unit–Company I, 138th Infantry, 35th Division–shipped off to Europe.

Much of that summer was spent training, but by autumn the 22-year-old Wold found himself in the trenches during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, a major part of the final Allied offensive of the war.

On the foggy morning of 26 September 1918, his unit and thousands of other Allied troops near Cheppy, France, made up the spearpoint of a massive drive to finally push the German Army out of France.

According to the 35th Division’s history, Wold’s company had been held up by several German machine gun nests, so he volunteered to sneak up on one of them. It was a success–he managed to silence the guns, kill some enemies, and bring back some Allied prisoners–so he sneaked up on three more nests. After silencing all four, he had brought back 11 prisoners

Later that day, Wold jumped from a trench and rescued a fellow soldier who was about to be shot, taking down the would-be enemy shooter in the process.

Nels Wold Before the War

His success was short-lived, unfortunately. Wold tried to sneak up on a fifth machine gun nest, but the Germans saw him coming and fired. He went down.

When Wold’s company realized he wasn’t coming back, they rushed the nest as a group and took out the enemy inside, dragging the injured Wold nearly a mile to safety, where he died telling his comrades to tell his family he loved them.

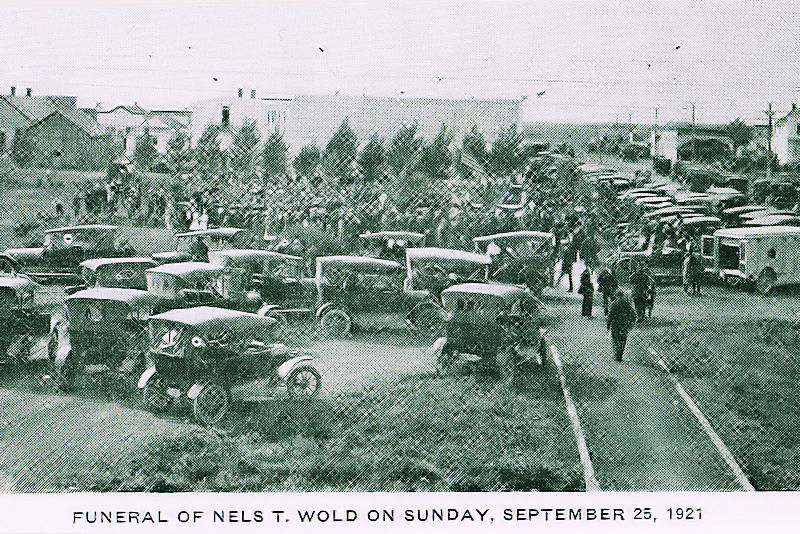

Wold didn’t survive, but his company was able to advance thanks to his courage. For that, he earned the Medal of Honor, which was given to his siblings by famed Gen. Leonard Wood during a ceremony in his hometown on 31 December 1919.

Wold was originally buried in France, but three years to the day after his death, his remains were returned and buried next to his parents in a cemetery near his hometown.

Source: "Medal of Honor Monday," Department of Defense, 28 January 2019

Wearing the Medal

Clockwise from Top Left: Lt Samuel Woodfill, 60th Infantry, 5th Division,

Sgt. Louis Cukela, 5th Marines, 2nd Division,

Capt. Edward Rickenbacker, 94th Aero Squadron,

Sgt. Sydney Gumpertz, 132nd Infantry, 33rd Division

Click on Individual's Name to Read His Medal of Honor Citation

Recipient: Lieutenant Willis W. Bradley, USN

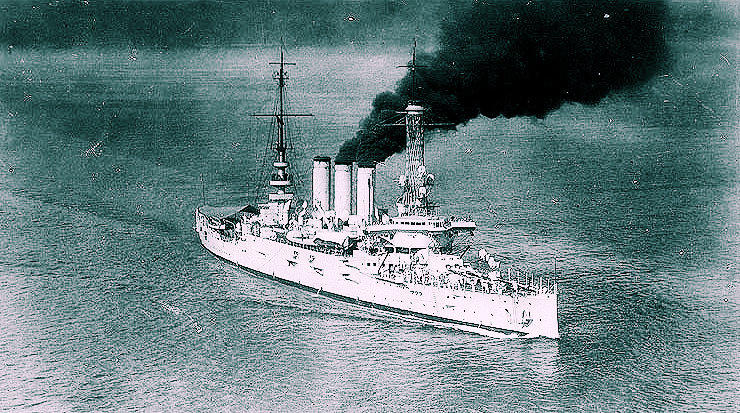

USS Pittsburgh

The first Medal of Honor recipient during World War I was a naval officer from North Dakota. On 23 July 1917, Lt. Willis W. Bradley undoubtedly saved his ship, the armored cruiser USS Pittsburgh, when ammunition cases exploded as they were being loaded into the ship's artillery enclosure.

Lieutenant Bradley

Bradley was blown back and temporarily knocked unconscious, but he crawled back into the burning enclosure after regaining consciousness. He saved a sailor and extinguished the burning materials located next to "a considerable amount of powder," preventing further explosions and likely saving the ship and crew.

Bradley was born on 28 June 1884, in Ransomville, New York, to Dr. Willis and Sarah Anne (Johnson) Bradley. When Willis, Jr., was only a few days old, the family took a train to Milnor in Dakota Territory. The family eventually settled in Forman, where the doctor established his medical practice. Because there was no high school in Forman, Willis, Jr., was sent to Hamline University preparatory school. He also took courses at the Archibald Business College and the Curtis Commerce College in Minneapolis. During the summers, he was deputy registrant of deeds for Sargent County.

His life changed, however, when in 1903, Bradley was appointed to the U.S. Naval Academy, which would lead to a long and interesting naval career. After graduating first in his class at Annapolis, Bradley was assigned to the battleship USS Virginia for sea duty and participated in the world tour of the Great White Fleet.

The USS Pittsburgh Between the Wars

After the World War, he served and commanded a number of ships and land installations, such as the Pearl Harbor docks, and took assignments with the Bureau of Ordnance. Bradley even served two years as governor of Guam. During World War II, he was commander of the Naval Inspection and Survey Board, with headquarters in Long Beach, California.

In August 1946, he retired from the Navy after 40 years of service. During 1947-1949, Bradley was elected as a representative of the Eighteenth District of California as a member of the Eightieth Congress of the United States. Willis W. Bradley died on 27 August 1954 and is buried at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery, San Diego, California. The USS Bradley (FF-1041), which was in service 1965-1988, was named in honor of Captain Willis W. Bradley.

Source: INFORUM, of Fargo, North Dakota

100 Years Ago:

|

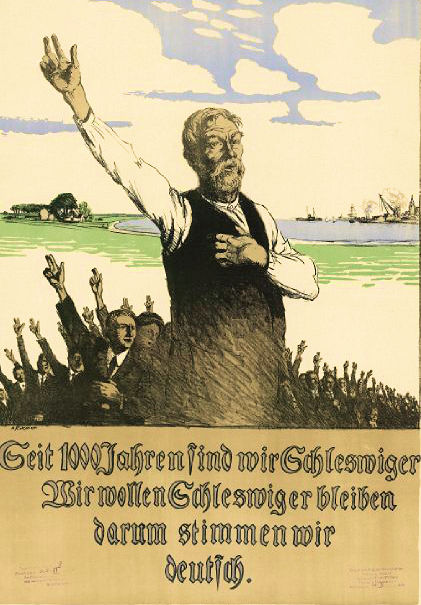

Pro-German 1920 German

|

The Treaty of Prague (1866), which had concluded the Seven Weeks’ War, provided that North Schleswig would be reunited with Denmark if the majority of that area voted to do so. In 1878, however, Prussia and Austria agreed to cancel this provision.

Following Germany’s defeat in World War I, separate plebiscites were held in 1920 in the northern and southern portions of North Schleswig so that their respective inhabitants could choose between Denmark and Germany. The northern part of North Schleswig voted 70 percent to join Denmark, while the southern part voted 80 percent to remain within Germany. The northern part of North Schleswig thus became part of Denmark as the Danish province of Slesvig, effective with King Christian X's ratification of the treaty with Germany on 6 July 1920. The resulting Danish-German boundary in Schleswig has lasted to the present day with a minor adjustment following the Second World War and is no longer a matter of contention.

Present-day Border (Compare to Historic Map Above)

Sources: Encyclopedia Britannica Article; Wikipedia

More World War I Vandalism in 2020

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (L)

Pettis County Courthouse, Sedalia, Missouri (R)

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications |

||

Order Our

|

Shop at |

Order the Complete Collection

|

A World War One Film Classic

For the second consecutive month, Gary Cooper stars in our World War One classic film. He won an Oscar for his performance as Medal of Honor recipient Alvin York in Howard Hawk's 1941 blockbuster. The movie was also nominated for the best picture award in that year. It was a tough field that included masterpieces Citizen Kane, The Maltese Falcon, and Hitchcock's Suspicion, but they all lost out to the intensely sentimental How Green Was My Valley. Go figure.

Surely, dear reader, you're familiar with Sergeant York's story, at least the screen version. A backhills man from Tennessee is drafted into the army and undergoes a difficult conversion from his deeply religious reluctance to kill to a willingness to become an effective infantryman. Later, in the middle of the Meuse-Argonne battle, when everything seems to be going wrong, he steps forward and accomplishes one of the most remarkable feats of arms in American history. By the way, the leaders of two different groups who have investigated York's action at the actual site on the Western Front have both told me that the battle sequence in the film is quite accurately depicted. I've been there, too, and the scenary looks right to me.

The film's supporting cast is also excellent and engaging, especially Joan Leslie as the home front sweetheart, Walter Brennan as his minister, and George Tobias as Pusher, York's best pal in the company. But it's Gary Cooper who owns the film. He was just so damn good about playing heroes – remember for example, the sheriff in High Noon, Lou Gehrig, "Pride of the Yankees", and Lt. McGregor of the Bengal Lancers? At his top form in Sergeant York, Cooper convincingly shows us the turmoil Alvin experiences in his transformations from country bad boy, to God-fearing pacifist, to master of the battlefield.

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon