September |

Access |

Belgium's Critical Contributions in 1914

The Admirable Resistance of the Belgian Soldiers

|

||||||||

|

To the Yser, Part I

By David Craig

Belgian Soldiers Defending Antwerp

An area of study often overlooked in any history of the First World War is that of events in Belgium between the declaration of war and the stabilization of the Western Front in late October 1914. The Belgian Army was regarded as an irrelevance by German planners. It was their intent to destroy Belgian fortifications that threatened German movement toward France, brushing aside the tiny and poorly trained Belgian Army while dealing with the remainder of Belgium at a later date. The tiny Belgian Army was composed of two parts: the garrison troops, who manned the fortresses on which defense largely relied, and the ground-maneuver troops, who manned entrenched positions between the forts and provided mobile operations.

German plans for dealing with Belgium proceeded as

planned. At Liège, the town was taken on 6 August, and

the major fortresses, which covered the Meuse

crossing, were shelled with newly arrived and specially

designed long-range Krupp 420mm siege howitzers on

the 12th, the final fort surrendering at 8:30 a.m. on the

16th. On the 19th, the Germans attacked the Namur

fortress, again with Krupp 420mm howitzers. By the

evening of the 23rd, five of the nine forts at Namur

were in ruins. At midnight the survivors of the Belgian

garrison made their escape. Any major Belgian threat

to the German advance into France was no more.

The Belgian Army retreated into the "National Redoubt" of Antwerp, where it was vainly hoped that the huge double ring of forts would enable a successful defense. The weakness of fortress defenses when attacked by German "super heavy" artillery was added to by the Belgian Army's clearing of the field of fire between the forts, an action which only improved the German ability to spot for their guns, which outranged those of the defense.

On 29 September the Germans attacked the outer ring

of forts. By 6 p.m. the first to fall, Wavre-Sainte-Catherine,

was so badly damaged it was abandoned. The British

Official History remarks that “The German shooting

was extraordinarily accurate and was, to all intents,

range practice, without hindrance from the Belgians,

whose guns were outranged. Practically all hits were

on vital parts of the forts.” On the same day Belgian

Army headquarters began planning the abandonment

of Antwerp and a move to Ostend.

The relief of Antwerp became a major concern. French

Supreme Commander Joffre, hard-pressed on all

fronts, could promise only a Territorial division and a

marine brigade from Le Havre as a French contribution,

to arrive around 10 October. The British, at the

instigation of Lord Kitchener, undertook to send their

7th Division and 3rd Cavalry Division, both then in

England.

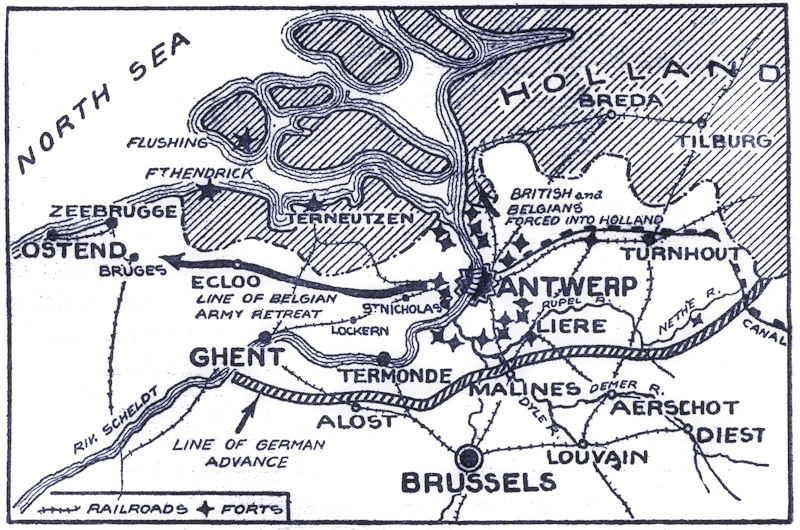

National Redoubt Antwerp & the Withdrawal West

Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, and ever

a man of action, did have men immediately available, a

brigade of Royal Marine Light Infantry under Navy

command. Hastily thrown together, this force arrived

at Dunkirk on 19/20 August. It had been augmented by

Royal Navy aircraft and armored cars. By 30

September this force was patrolling the area between

Dunkirk and Cassel. On 3 October, Churchill himself

travelled to Antwerp and offered British help to the

Belgian government. On the same day, four battalions

of the Royal Marine Brigade set off for Antwerp,

arriving by train at 6 a.m. on 4 October.

On the night of 7/8 October the British 7th Division and

3rd Cavalry Division landed at Zeebrugge and

concentrated at Bruges, with orders to cooperate with

French forces in Belgium and support the Belgian Army

defending Antwerp. However, on the 6th, the Belgian

Field Army had already crossed the Scheldt River to

facilitate a withdrawal, and the situation in Antwerp

itself had continued to deteriorate. The only good

news was that the long-delayed French aid, in the form

of a brigade of French Marines, had left Paris on the

way to Belgium.

On the morning of 8 October the decision was made to

evacuate Antwerp in the face of increasing German

pressure. The withdrawal was made in some confusion

over the next 48 hours, with the majority of the Royal

Marine brigade withdrawn. The British force,

which meanwhile had landed at Zeebrugge, was

placed under the command of Sir John French of the

BEF, moved from Ghent toward Ypres. The remains of

the Belgian field army, dispirited and in some disorder,

joined civilian refugees clogging the roads to the coast

or made their way into Holland. After more than two

months of continuous action against overwhelming

odds, they were exhausted and needed rebuilding, but

they still existed.

When the Germans accepted the surrender of Antwerp

on the morning of 10 October, they found only the

military governor, his staff officer, and a handful of

men from the fortresses. The rest had successfully

escaped. The Belgian stand at Antwerp, while failing to

hold the city, bought the BEF and the French valuable

time and employed large numbers of German troops

that would otherwise have been available to fight in

the crucial battles on the Marne and Aisne rivers.

The Belgian Army Marching to the Yser

Proposals for the Belgian Army were that it should

withdraw west of Calais to regroup. Albert saw two

great dangers in this. He knew that any attempt to take

his army under French command would be resisted by

his Dutch-speaking soldiers (who made up most of the

lower ranks), and he also saw that if he abandoned

Belgian soil he could be usurped as king. It was finally

agreed that the Belgian Army would concentrate in the

Dixmude-Nieuport-Furnes area, just inside Belgium,

with the French marines of Admiral Ronarch on their

right in Dixmude. By the 14th of October, the Belgian

Army started to prepare positions along the Yser, and It

would be this small strip of Belgium which would be

defended by Belgian soldiers, commanded by their

own king, until the end of the war.

(Part II continues below)

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

Different Perspectives

There was a lot of action throughout Belgium in 1914. Here are some additional sources of material.

![]() Overview of Belgium's War

Overview of Belgium's War

![]() The Destruction of Louvain

The Destruction of Louvain

![]() Were There Atrocities in Belgium?

Were There Atrocities in Belgium?

![]() The German Failure in Belgium (Book Review)

The German Failure in Belgium (Book Review)

![]() Slowing Down the Schlieffen Plan

Slowing Down the Schlieffen Plan

![]() The Trench of Death at Diksmuide

The Trench of Death at Diksmuide

![]() The Armored Cars of Antwerp

The Armored Cars of Antwerp

![]() Eyewitness: A German Soldier Marches Into Belgium

Eyewitness: A German Soldier Marches Into Belgium

![]() The Battle of the Yser, 1914

The Battle of the Yser, 1914

![]() A Guide to the WWI Battlefields of Belgium

A Guide to the WWI Battlefields of Belgium

![]() Alfred Bastien's Panorama de l'Yser

Alfred Bastien's Panorama de l'Yser

King Albert's Message to Parliament

In the name of the nation, I give it a brotherly greeting. Everywhere in Flanders and Wallonia, in the towns and in the countryside, one single feeling binds all hearts together: the sense of patriotism. One single vision fills all minds: that of our independence endangered. One single duty imposes itself upon our wills: the duty of stubborn resistance.

In these solemn circumstances two virtues are indispensable: a calm but unshaken courage, and the close union of all Belgians.

Both virtues have already asserted themselves, in a brilliant fashion, before the eyes of a nation full of enthusiasm.

The irreproachable mobilization of our army, the multitude of voluntary enlistments, the devotion of the civil population, the abnegation of our soldiers' families, have revealed in an unquestionable manner the reassuring courage which inspires the Belgian people.

It is the moment for action.

I have called you together, gentlemen, in order to enable the Legislative Chambers to associate themselves with the impulse of the people in one and the same sentiment of sacrifice.

You will understand, gentlemen, how to take all those immediate measures which the situation requires, in respect both of the war and of public order.

No one in this country will fail in his duty.

If the foreigner, in defiance of that neutrality whose demands we have always scrupulously observed, violates our territory, he will find all the Belgians gathered about their sovereign, who will never betray his constitutional oath, and their Government, invested with the absolute confidence of the entire nation.

I have faith in our destinies; a country which is defending itself conquers the respect of all; such a country does not perish!

Albert I, King of the Belgians, 4 August 1914

The Strain of Occupation

[A] mid-1917 report by Governor-General von Falkenhausen stated that the occupation regime was detested as much as ever, but that the occupied Belgians detested one another, too. Various segments of society accused others of profiteering; the burden of “sacrifice” seemed unequally borne.

Occupied Belgium was riddled with class tension. Relief arrangements broke with old laissez-faire attitudes but did not question hierarchies of class and gender. Impoverished middle-class people did not have to queue for soup. Soldiers’ wives received aid in kind; officers’ wives had an allowance. Most women received relief (a form of charity) instead of unemployment benefits (a social right). In addition to the tensions generated by relief arrangements, the occupation regime’s deportation of the jobless hit only the working classes, thus dividing those who had to live under this spectre (or who took on “voluntary” work as a last resort) from those who did not.

Alienation also ran along generational lines: young men, especially, found themselves resented by patriots with sons at the front. Young bourgeois men were under especial pressure to try to escape and enlist in the Yser army, in spite of terrible danger. In response, some accepted the occupation regime’s offers of higher education and of employment. Young literati defied convention, published in new magazines, and made German friends. Others, more compromisingly, worked for German counterespionage.

Sophie De Schaepdrijver, 1914-1918 Online

The Wrath of Big Bertha

I am wrong there. We did not look at what was left of Fort Loncin. Literally nothing was left of it. As a fort it was gone, obliterated, wiped out, vanished. It had been of a triangular shape. It was of no shape now. We found it difficult to believe that the work of human hands had wrought destruction so utter and overwhelming. Where masonry walls had been was a vast junk heap; where stout magazines had been bedded down in hard concrete was a crater; where strong barracks had stood was a jumbled, shuffled nothingness.

Standing there on the shell-torn hilltop, looking across to where the Krupp surprise [the 420 mm howitzer known as Big Bertha] wrote its own testimonials at its first time of using, in characters so deadly and devastating, I found myself somehow thinking of that foolish nursery tale wherein it is recited that a pig built himself a house of straw, and the wolf came; and he huffed and he puffed and he blew the house down. The noncommissioned officer told us an unknown number of the defenders, running probably into the hundreds, had been buried so deeply beneath the ruins of the fort in the last hours of the fighting that the Germans had been unable to recover the bodies. Even as he spoke a puff of wind brought to our nostrils a smell which, once a man gets it into his nose, he will never get the memory of it out again so long as he has a nose. Being sufficiently sick, we departed thence.

Irving S. Cobb, Paths of Glory

To the Yser, Part II

By David Craig

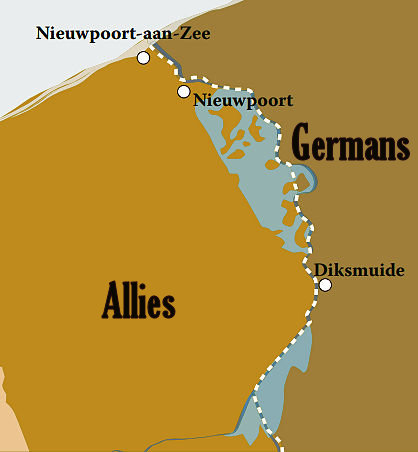

As the Belgian engineers began the task of constructing defences along the Yser, they became aware

of French intentions to flood low ground around

Dunkirk, a move which would run the risk of them

being trapped by water behind them and the advancing Germans to their front. The obvious solution was to inundate the low-lying farm land running

from Dixmude, some nine miles inland, to Nieuport, on

the Belgian coast, thus producing a major obstacle to

stop the German advance. The low-lying ground of the

area was below high tide level and even the canalized

rivers flowed between embankments, the water level

higher than the surrounding land.

The Yser Line &

Inundated Area

A major problem was that the Belgian Army engineers

did not understand the complex relationships

governing the dykes, weirs, and locks that operated

the drainage. Moreover, the engineers tended to be

the Flemish descendants of the Dutch, who had

drained the polders in the first place, and naturally did

not take kindly to misinformed army francophone

efforts to order them about or to damage the system.

In particular, the Army failed to realise that a key figure

was the man responsible for operating the complex

system of drainage and navigation locks at Nieuport,

Lockmaster Dingens, with 40 year's experience in the

Waterways Department.

Dingens was not cooperative with the demands of the

Army. On 16 October, the first Germans arrived and

started to dig in at Westende, half a mile from

Nieuport. The next day, the inhabitants of Nieuport were

ordered to leave or be prepared to take to their cellars

when the German bombardment started.

By the 17th, ships of the Royal Navy's Dover Patrol

were off Nieuport ready to give naval gunfire support

to French and Belgian defenders of the Yser, first

engaging German positions on Sunday the 18th with

two cruisers and three monitors, as well as smaller

vessels. Despite this, German troops advanced to

Lombardsijde, less than 600 metres from the crucial

lock complex known as the Goosefoot, which included

Lockmaster Dingens's house. Among the refugees

moving into France under German fire were Dingens

and his family together with most of the other key

waterways workers.

Hendrik Geeraert, Hero

If the German Army had been able at this point to

secure a crossing over the Yser River there would have

been little to prevent the Allied line being in grave risk

of being turned. What happened next is one of those

accidents of history that are almost unbelievable. On

21 October Major General Daufresne of the Belgian 2nd

Army Division sent an order to Major Le Clement,

commanding the engineer unit at Nieuport, to flood an

area known as the Nieuwendamme Polder. Like any

good officer commanding, Le Clement sent a written

order to his man on the ground, Second Lieutenant

Françoise, telling him to set up a flood and instructing

him to work with the lock keeper on how this should

be done. Françoise replied that the lock keeper had

gone and asked for further instructions. At this point

one of Françoise's men, Corporal Ballon, had been

drinking with a tugboat captain, Hendrik Geeraert, who

knew the workings of the lock system and explained

that he had a friend, a drainage supervisor named Karel Cogge, who might be able to help.

Cogge was approached and immediately volunteered to assist.

While Geeraert knew how the lock system worked,

Cogge knew precisely which locks should be opened

and which watercourses manipulated in order to

inundate the land as rapidly as possible. Cogge

estimated that, if the openings under the railway

embankment were all sealed and an old inundation

lock at Nieuport used to let the seawater in, in concert

with the locks in the Goosefoot being held closed, the

land between the Yser river and the railway could be

satisfactorily flooded in three successive high tides to

the requisite depth, too deep for troops on foot but

not deep enough to allow large boat passage.

On the evening of Sunday 25 October, Belgian Army

engineers started work on preparing the area to be

flooded. Exhausted soldiers, working with whatever

materials were at hand, started to make the railway

embankment watertight. In the small hours of the 28th,

Cogge supervised the final part of the plan, when the

Spanish lock at Nieuport, now under German

observation during daylight, was secured in the open

position to allow the rising tide inland.

Karel Cogge, Hero

On the 29th, Hendrik Geeraert, together with a small

group of soldiers, crept across the Goosefoot locks,

now in no-man's-land, to open a further crucial group

of paddles in the Vaart lock gates, hastening the tidal

flood. Six hours later the 16 paddles were closed. They

did the same on the two following nights. Realizing the

importance of these locks, the Belgian Army reoccupied

the area. Belgian Army engineers would control the

flooding for the rest of the war, constantly under

German artillery bombardment.

On 30 October the Germans launched eight infantry

regiments on a six-mile front in an attempt to force the

railway embankment before the rising water defeated

them. In the little village of Pervyse, Belgian soldiers of

the 13 and 10 infantry regiments, together with a

battalion of French Chasseurs, repelled the attackers

and took 200 prisoners. The Germans succeeded in

taking Ramscappelle but, observing the water behind

them was still rising (ankle-deep in the morning the

water was knee-high by midday,) started to filter back

across the rising flood. The inundation continued to

rise while the last few isolated farms still held by the

now-marooned enemy were taken.

On the morning of the 31st, a Franco-Belgian attack was

launched on the Germans in Ramscapelle, but General

von Beseler, commanding the German Third Reserve

Army Corps, had already ordered a withdrawal across

the Yser, a defeat engineered in no small part by two

civilians, Hendrik Geeraert and Karel Cogge.

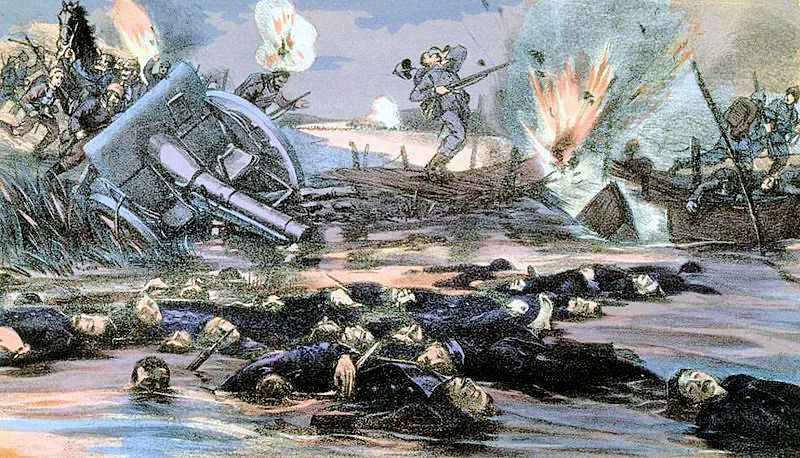

The Inundation at Ramscapelle

Ed. Note: This was one of the decisive setbacks of the Great War. It was never reversed: the Channel ports supplying the British Army never fell and an immovable anchor was set on the northern end of the emerging Western Front. Farther south on 31 October, the fighting west of Ypres was giving the German Army one last opportunity for a breakthrough that could flank and roll up the entire Allied position. That attack failed and from that moment the Western Front from the Channel to the Swiss border was locked in. Trench warfare had begun.

Excerpted from David Craig's article "The Road to the Yser," originally published in the April 2012 issue of Over the Top.

Meanwhile, the Civilian Population Suffered

Almost as soon as Germany invaded neutral Belgium on 4 August 1914, numerous reports came in of German troops killing and mishandling civilians. In the weeks that followed, those reports turned into a deluge of killings, burnings, wholesale executions of hostages, including civilian men, women, and children. There were too many such reports to ignore.

Naturally, the Allied press reprinted the reports in length. The German atrocities also spawned dozens and dozens of illustrations created by artists and illustrators, mainly because of lack of photographic material or because the photos of dead and mutilated civilians were too horrid to be shown in print at the time. Many of the resulting illustrations were over the top and especially dramatically composed, drawing on theatrical traditions of posing actors/people in certain recognizable poses indicating emotions and drama. To people in these modern times, such artwork often looks overly dramatic and contrived, not realistic at all. But in this case, the vignettes presented in the illustration are not exaggerated and only show the killing and mistreatment of civilians by German soldiers. By year's end, some 5500 Belgian civilians were deliberately killed in one way or another by Germans, probably in far more horrid and violent instances than depicted here.

The drawing here comes from a popular French publication as a sort of collectible, a war-time collectors card, printed on cheap paper, like the parent publication itself (Le Petit Journal, a Parisian daily with Sunday color supplement). Tony Langley

Albert I, King of the Belgians & National Hero

By Tony Langley

Albert I succeeded to the Belgian throne in 1909 and ruled until his death in 1934. He was the third king of the Belgians to reign since the independence of the country in 1830. Like many of the ruling family, he was a devout Catholic, but he was also a social progressive pushing for universal suffrage and for linguistic equality between the two language groups making up the country.

His reign is mostly associated with the Great War, during which virtually the whole of Belgium was occupied by the Germans. Constitutionally at the head of the armed forces during time of war, he led the country through these difficult times while gaining an international reputation for heroism and integrity. He was idealized in the written and illustrated Entente and Allied media during the war, while at the same time being mistrusted by war leaders and politicians. Both Britain and France feared that Albert I might make a separate peace with the Germans. That is why his government and military were never informed about or participated in any of the great Allied offensives until the very last months of the war. The Belgian overall strategy was to wait out events and hope for the best. In the last weeks of the war, Albert's forces, supplemented by French and American divisions, went on the offensive.

His strategy was borne out by events, and Albert I returned to a liberated Belgium, welcomed as a returning hero, ever steadfast in his resolve. After the Great War his stature and personal integrity were unquestioned. An avid mountaineer and rock climber, he died in an accident while climbing in 1934. He would not be available when Belgium was once again threatened with invasion five years later.

Antwerp, Belgium

In the postwar years, towns and cities in many countries vied to erect public monuments commemorating the war. Even Paris has an equestrian monument of King Albert. The memorial in Antwerp shown above is one of many that were built during this period. An equestrian Albert dominates the ensemble. which includes side groupings of Belgian soldiers and mourning families. Dedicated in 1930 in the presence of the king and queen themselves, it was of a grand design in the realistic school, one of the more ornamental and imposing monuments to the Great War in Belgium. Its official title is "Monument for the Dead." It was designed and sculpted by Belgian artist Edward Deckers.

100 Years Ago:

|

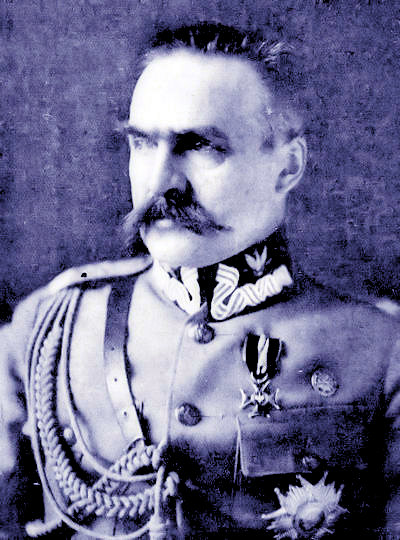

Pilsudski |

The Polish-born and much-feared head of the Cheka (Bolshevik secret police), Feliks Dzerzhinsky, was made head of a Polish Revolutionary Committee, which would follow the Red Army and form the new government. Lenin was absolutely confident of success. Initially all went well, and within six weeks the Red Army was at the gates of Warsaw. But as the Polish Communists had warned, all classes did indeed unite, and there was no uprising in the city. Also the Polish commander, Jozef Pilsudski, drew up a bold, if not foolhardy, plan of counterattack. The Polish army would stand on the defensive in front of the city, and when the Red Army was fully committed to the battle, Poland’s best units would launch a flanking attack from the south, cut the Bolshevik lines of communication, and encircle much of the Red Army. Some Polish generals were aghast at the risks involved, but in their desperation, there seemed no alternative.

Aftermath: Polish Officers Gathering Soviet Battle Flags

When the Red Army launched what was expected to be the final assault on Warsaw, Pilsudski had to begin his counterattack 24 hours early, with some units not yet in position, for fear that Warsaw might fall if he waited. The Red Army fought its way to the village of Izabelin, only 8 miles (13 km) from the city, but the Polish attack succeeded beyond wildest expectations. Driving through a gap in Bolshevik lines, the Poles advanced rapidly against little opposition. In the Red Army, all was chaos; commanders lost control of their units, with some divisions continuing their advance on Warsaw, others fleeing. Three armies disintegrated, and thousands fled into East Prussia, where they were interned. In an encounter that saw Polish lancers charging and overwhelming Bolshevik cavalrymen, the First Cavalry Army, trapped in the "Zamosc Ring," was all but annihilated.

The Fourth Army meekly surrendered after being encircled. Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky desperately tried to pull his troops back to a defendable line, but the situation was beyond redemption. A few more engagements followed, but the war was effectively won. Lenin was forced to agree to peace terms that surrendered a large tract of territory whose population was in no way Polish—the Red Army returned to reclaim it in 1939.

Sources: Encyclopedia Britannica article by John Swift, Univ. of Cumbria

Yes, the Menin Gate Last Post Ceremony Continues

Alas, with Buglers Only

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications |

||

Order Our

|

Shop at |

Order the Complete Collection

|

A World War One Film Classic

Did you like Dr. Zhivago? The lush photography? The top-of-of-the-line acting? The combination of Russia in catastrophic upheaval in the background and a compelling love story front and center? If so, then the 2016 Russian-produced epic with the mushy English title The Heritage of Love is just for you. (However, the marketing genius who decided to abandon the very cool and to the point original title– Hero in English, Geroy in Russian–should receive a special "Razzie" award.)

The utterly improbable and claimed to be true (I don't care one way or the other) multi-generational love story begins in recent Paris and switches back and forth to the Imperial Russia of a century earlier. In the present-day setting, we get acquainted with Vera, great-granddaughter of a princess named Vera, and Andrey, the great-grandson of another Andrey, an officer of the Tsar's Army and, later, the Whites. As the movie unfolds, the Paris-based couple discovers other odd coincidences connecting their ancestors, while the audience, with the help of flashbacks, stays a few steps ahead of them. Through the eyes of the earlier Vera and Andrey, these historical sequences cover the history of Russia from the immediate aftermath of the Archduke's assassination to the flight of the White Russian émigrés after their defeat in the Civil War. Though I'll have to remain silent on the fates of the then and now romances, I'll bet the reader can make a pretty good guess about both.

For film buffs and students of the Great War, there are many things to like in The Heritage of Love. As you would guess, the same perfectly-cast individuals play the old and new Vera and Andrey and, in their current-day modes, both succeed in capturing some of their inherited qualities of their namesakes, while also displaying some unique and modern quirks. The feeling of authenticity—dress, manners, military equipment and weaponry—for both ends of the storytelling is especially pleasing. Maybe the thing that impressed me most was the script by Nataliya Doroshkevich and Olga Pogodina-Kuzmina. Sometines the jumps in time were a little jarring, both otherwise, they effectively told two interesting tales and melded them in a very satisfying denouement. And most impressive, they accomplished this in 80 minutes, about one-third the length of Doctor Zhivago. Available for purchase or streaming through Amazon Prime. MH

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon