October

2019 |

|

|

|

Reclaiming Flanders

The Present-Day Fertile Farmland of Passchendaele Ridge Viewed

from Tyne Cot Cemetery Today

Meeting King Baudouin

In an article below on the Cloth Hall of Ypres, readers will see a reference to a former monarch of Belgium, King Baudouin. I thought you might like to know that on a bitterly cold day in January 1990, I got to meet His Majesty and chat up the Great War with him.

Earlier that day, I had decided to ignore my sneezing and running nose and abandon my comfortable hotel room in Brussels to go explore the Waterloo battlefield. At the village train station, I hired a local cab driver to be my guide, and he suggested our first stop should be the artificial "Lion's Mound" that provides an overlook to the battlefield. There were no cars in the parking lot when we arrived and not another tourist to be seen on the entire horizon. Two-hundred and twenty-six steps later, I found myself, huffing and puffing, on the path that circles its peak. Moving toward the side facing the main sites, I was surprised to meet a party of three: a tall fit-looking younger fellow, who I soon realized was a security man, an older portly gentleman, who turned out to be a historian, and a third man, about 6-foot tall, of considerable dignity, but very thin, almost emaciated looking, even in a topcoat.

Just from the positioning and body language of his compatriots, it was clear this third person was the leader of the group. I also gathered that his two subordinates were not especially happy to see me. The academic was frowning and the larger chap seemed to be reaching in his jacket for something. I immediately assumed a maximally friendly posture and announced, "Well, hello—what a surprise!" The slender man responded, "Ah, an American." At this point, I went all in and stuck out my hand towards him and said, "I'm Mike Hanlon; I'm from the Bay Area in California." To which he responded by offering his hand and saying with a slight smile, "I'm Baudouin." I still feel embarrassment at mentioning this almost 30 years later, but when we shook hands, I had no idea that the King of Belgium was named "Baudouin." Something about the way he said his name, though, gave me pause. Fortunately, with great aplomb and a slightly bigger smile, he let me off the hook, by adding, "I'm King of the Belgians."

After my stumbling apology things relaxed considerably, though. I learned he was there on a reconnaissance to prepare for the upcoming 175th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo. The King introduced his historical adviser on the event, who filled me in on some of the improvements planned for the commemoration. The conversation was winding down when I mentioned that the main purpose of my visit to Belgium was to visit the World War I battlefields in Flanders. With this, the King became very animated and asked the specific things I planned to see. He was clearly more interested in the Great War than Waterloo. After listening to my list, which was focused on the Ypres Salient, his historian advised that I shouldn't miss Nieuport, the Trench of Death, and Käthe Kollwitz's Grieving Parents–all sites in the Belgian sector the war, by the way. His Majesty added his own comments, remarking that he had learned as a boy his grandfather, King Albert, had been proud to have commanded American troops during the fighting. We were having a grand old World War One back-and-forth when my cold symptoms kicked in with a vengeance. As I stepped away from the party to deal with a major sneezing fit, the King and his aides signaled their departure and the group headed for the stairway with some alacrity. Thus ended my singular encounter with royalty. My cab driver, who had subsequently seen a limousine pick up the king and his party down at the base of the hill, was pretty impressed, however, when I told him I'd just spent 20 minutes chatting with his monarch. MH

Flanders After War

The Flanders Battlefield in 1919

For thousands of Belgian people, the signing of the Armistice

on 11 November 1918 marked the beginning of another grim

struggle that was to last for decades.

It’s easy to think of the relief and optimism sweeping across

Europe that the signing of the peace treaty must have brought.

Perhaps we have visions of people returning to their homes in

previously occupied territories, greeting loved ones, restocking

the shops, and getting “back to normal.” Or we imagine citizens

and soldiers dancing in the streets of villages and towns, to the

pealing of church bells.

But for thousands of Flemish people returning to Flanders

Fields, the reality was totally different–and brutal. For them,

there were no bells pealing from village churches. There was

no dancing in the streets. There was no restocking of shop

shelves.

Why? Because there were no churches, no shops, no streets.

In fact, there were no villages, nor towns.

There was absolutely nothing remaining of the land they used

to know. In Flanders the front Line extended from Nieuport

on the coast, along the banks of the previously picturesque

River Iser, past Diksmuide, around the medieval town of Ypres

and past Mesen to the French border. Its width varied between

two and ten kilometers. On a clear day, a Belgian soldier would

have been able to stand in relative safety behind the front line

and see the German army moving in relative peace on the

other side.

The land in between, however, was a monstrous hell of death

and destruction. In this long, narrow stretch of West Flanders,

more than half a million soldiers were killed, wounded or

missing. Tens of thousands of civilians were forced to flee for

their lives. Towns, villages, farms, woods, and fields were totally

devastated. The area became known as the Verwoeste

Gewesten–the Devastated Lands. What happened next and

how the landscape was restored to its previous state is a

remarkable story of the perseverance and opportunism of the

Flemish people.

Ypres Immediately After the War (In Flanders Field Museum)

The towns in the battle zone suffered massive damage. Ypres—having been

utterly leveled and being the location of the world-famous Cloth Hall, was especially

a challenge. The idea of not reconstructing the city and leaving Ypres in ruins as a memorial had been suggested during the war. It was thought that a new city could be built nearby and not on the rubble of the destroyed city.

In July 1919 the British government succeeded in getting agreement from the Belgian government to create a “Zone of Silence” in the area of the destroyed Cloth Hall, belfry and St. Martin's cathedral. However, this was not willingly accepted by all of the local people in Ypres and after two years it was agreed that the British would be able to build a monument in Ypres instead. The location was agreed for the construction of a large memorial, the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing, to be built on the old eastern access route in and out of Ypres.

By 1920 the number of people living in Ypres was about 6,000. The population grew significantly during the 1920s and there were already about 15,000 people in the city by 1930. More than half of the 15,000 inhabitants were, however, people who had moved there after the war and had not been born and brought up in the city before 1914. Many of the families who had lived in and around Ypres for generations had decided not to go back.

After the Armistice, two action plans for rehabilitating Flanders were hastily formulated and

implemented. The first was to retrieve, identify if possible, and

bury the bodies of the soldiers who had died on the front. Many

of these had lain unburied for years and all clues to their

identity had been lost. Others had been buried in temporary

graves. These were exhumed and laid to rest in permanent

cemeteries.

The second task was to level the ground. The British Army’s

Chinese Labour Corps played a key role in this work. Initially

shipped over from China to dig trenches and latrines and

provide other support to the fighting soldiers, they stayed in

Flanders after 1918 to help clean up the war zone. They did

not return to China until 1920. German prisoners of war were

also used. Trenches, craters, and shell holes were filled in, and

at some point it was declared that civilians could be allowed to

re-enter the war zone. They were told to expect the worst.

It would have been an extremely traumatic return–a nightmare

scenario. One farmer returned to his farm, found absolutely

nothing recognizable, and committed suicide. Another man

from Ypres couldn’t find a trace of his farm until he found a tap to

an underground water pipe that he had installed in 1914. It

was the only thing remaining of his property.

Their first priority was to build temporary accommodation, and

the resourcefulness and ingenuity of the Flemings came to the

fore. Scattered around the battlefields were huge dumps of

wood and scrap iron. Using such materials, basic huts and

sheds were constructed.

Author and British Veteran Henry Williamson Discovered a Destroyed Tank Still Sitting on the Battlefield Near Zonnebeke During His 1925 Honeymoon (Henry Williamson Society)

Other families took over abandoned Nissen huts. These were

prefabricated, portable multi-purpose huts developed by Major

Peter Nissen of the Royal Engineers in 1916. At least 100,000

of them were produced in World War One as temporary

barracks for soldiers. The Belgian government also provided

their people with temporary wooden huts.

The availability of clean drinking water was a problem. The

River Iser and the two lakes that provided water to Ypres were

totally contaminated and unfit to drink. Local breweries came to

the rescue. They drilled deep boreholes and pumped up

clean water. They used it for their own brewing processes and

to provide potable water to local inhabitants.

The next task was to redevelop and re-stock the land. This

was necessary not only in the war zone itself but up to ten

kilometers on either side. One of the reasons was the

extensive use of chlorine, phosgene, and mustard gases in the

region. These poisonous gases were not only fatal to humans

but killed everything living in their path, including livestock as

well as vegetation. The Belgian Ministry of Agriculture provided

new seeds and plants, while farmers in the Netherlands–particularly from the province of Limburg–donated cattle,

horses and even chickens. Slowly but surely, new life began to

return to the Devastated Lands.

However, working in Flanders Fields in the early 1920s was a

dangerous occupation. It has been estimated that a quarter of

the failed to explode but remained live. Flanders' farm laborers were constantly being maimed or killed by unexploded ordnance. It was apparent that the initial clean-up operation had been too superficial.

Around this time some clever opportunists appeared on the

scene. They would perform a service of “deep digging.” For a

fee they would thoroughly dig out a hectare of land, remove all

the shells, and proclaim it as clean land. A number of family

fortunes were made in this way.

Also amassing great personal wealth were the scrap metal

merchants who went from battlefield to battlefield collecting

shells and selling the iron and copper. Both jobs were fraught

with danger and frequently led to workers losing limbs, if not

their lives. Unbelievably, the so-called Period of Reconstruction

of the Verwoeste Gewesten lasted until 1967, when the final

annex to the Cloth Hall in Ypres was finished.

Sources: Discovering Belgium, The Great War, 1914-1918 Website, the Henry Williamson Society, Wikipedia

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

|

|

The Iron Harvest

Each year, nearly 300 tons of rusting bombs, grenades, mortars, and shells are unearthed in Flanders. About one in 20 contains poison gases that are still potent enough to kill. The locals call it the “Iron Harvest.” The job of finding the munitions and making them safe in Belgium falls to the Explosive Ordnance Disposal Service (DOVO), which recovers between 150 and 200 tons each year. More than 20 members of the unit have been killed since it was formed in 1919. The old explosives, however, have taken a much greater toll among civilians, who have accidentally encountered them. In the Ypres district alone, over 600 have died since the Armistice.

Found at Varlet Farm, Poelkappelle

Battle Remains on the WW1 Western Front

Battle Remains on the WW1 Western Front

Atlantic Magazine's Photo Album of the Western Front

Atlantic Magazine's Photo Album of the Western Front

Assessing the toxic legacy of First World War battlefields

Assessing the toxic legacy of First World War battlefields

Flanders 1921 (Photos)

Flanders 1921 (Photos)

Bombing During World War I

Bombing During World War I

Flanders Iron Harvest Today

Flanders Iron Harvest Today

Two Workmen Die in Ypres

Two Workmen Die in Ypres

Case Study: Varlet Farm Near Poelkapelle by Charlotte Descamps (PDF)

Case Study: Varlet Farm Near Poelkapelle by Charlotte Descamps (PDF)

Belgian Bomb Disposal Today (Video)

Belgian Bomb Disposal Today (Video)

A war never ends

This is one of the arguments

against any war: a war never

ends. Even when peace is

declared, even when the armies

have left and the generals are

counting their decorations, a

war continues to hang, like a

menacing scythe, over the local

population. Not only here, but

in any battlefield, anywhere in

the world.

Luc Dehaene, Mayor of Ypres, 2010

Gas Warfare in Flanders

DOVO Storage Yard, Ypres

It is well-known that the first major use of gas on the Western Front was at the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915. However, several other chemical warfare "milestones" took place in Flanders: chlorine, phosgene, blue cross, and mustard gas were all first used on the Belgian front, and Yperite derived its name from its use in Belgium. Civilians near the battlefields also suffered from their use during the fighting. In the last month of the war 27 civilians were reported killed by Yellow Cross (Mustard-type) gas at Hansbeke.

Returning to Flanders

Yes, there was no

doubt about it. It is the big pasture at R33 on

the map. How often he came back there, he

cannot think, but it is the place he remembers

best, in all those wanderings from camp to billet. It is what he has been looking for, the reason of

his detour by out-of-the-way Hondebecq, instead

of following the usual route of tourists, visiting

the Front.

The thing they call the Front, preeminently a place where men have died, soon saddened and sickened him, but at R33 perhaps one might catch a glimpse of the place where men

had lived. Better here than anywhere else. The

biggest and best known camp was only a war-time

affair, inhabited by soldiers, cleared away since

the Armistice. But the low two-storied old house,

there at the back of the pasture, under the elms

and round its cobble-edged manure heap, is a

place that had kept its civilian character all through the War, and has survived, more or less intact, now that War is gone. He looks and

looks and slowly he understands why it seems so

strange. The pasture is empty. Not a soul

stirs. Not even a pig is in sight. Leaning on

the gate, he closes his eyes, to recall how it used

to look.

Slowly the picture comes back. The

quagmire about the gate, the “road” built of

faggots and brick-ends from bombarded buildings that led to the house, the tents to the left,

the transport parked to the right. He can feel the rough surface under his feet, can hear the

lugubrious jollity of men doing odd jobs, the

squawking and fidgeting of the mules, being as awkward as possible. At the corner of the barn,

to the left, the cookers blacken everything, but on

some of the hard ground just by the entry, the lip

of the old dry moat it may have been, a party of

men are falling in, to go up to the line for some

special duty. He passes in front of them,

watching the N.C.O. checking their equipment . . .

He opens his eyes, and the sound, the sight, the

odor vanish. Nothing! There is nothing there. Some birds are chattering in the elms, the greyish

spring day is waning. It is no good standing there waiting for something to come back, which

will never come back. At least one hopes not. He has still some time to put away before his

train, he will follow the lane down to the pave,

have a last glance from the high land there, and so back to the village and the station. That will be

a good wind-up, for he feels that he will not come that way again.

From: The Spanish Farm Trilogy, R.H. Mottram

I must return to my old comrades of the Great War–to the brown, the treeless, the flat and grave-set plain of Flanders–. . . for I am dead with them, and they live in me again.

From: The Wet Flanders Plain, Henry Williamson

Gallipoli

From: National World War I Museum / Clive Harris & Mike Sheil, Tour Leaders

When: October 2019

Details: Itinerary and Tour FAQ

HERE.

National WWI Museum 2019 Symposium

1919: Peace?

When: 1-2 November 2019

Where: Kansas City, MO

Details:

HERE.

Mid Atlantic, League of WWI Aviation Historians

Chapter Meeting

When: 23 November 2019

Where: Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, near Dulles International Airport

Details:

HERE.

|

|

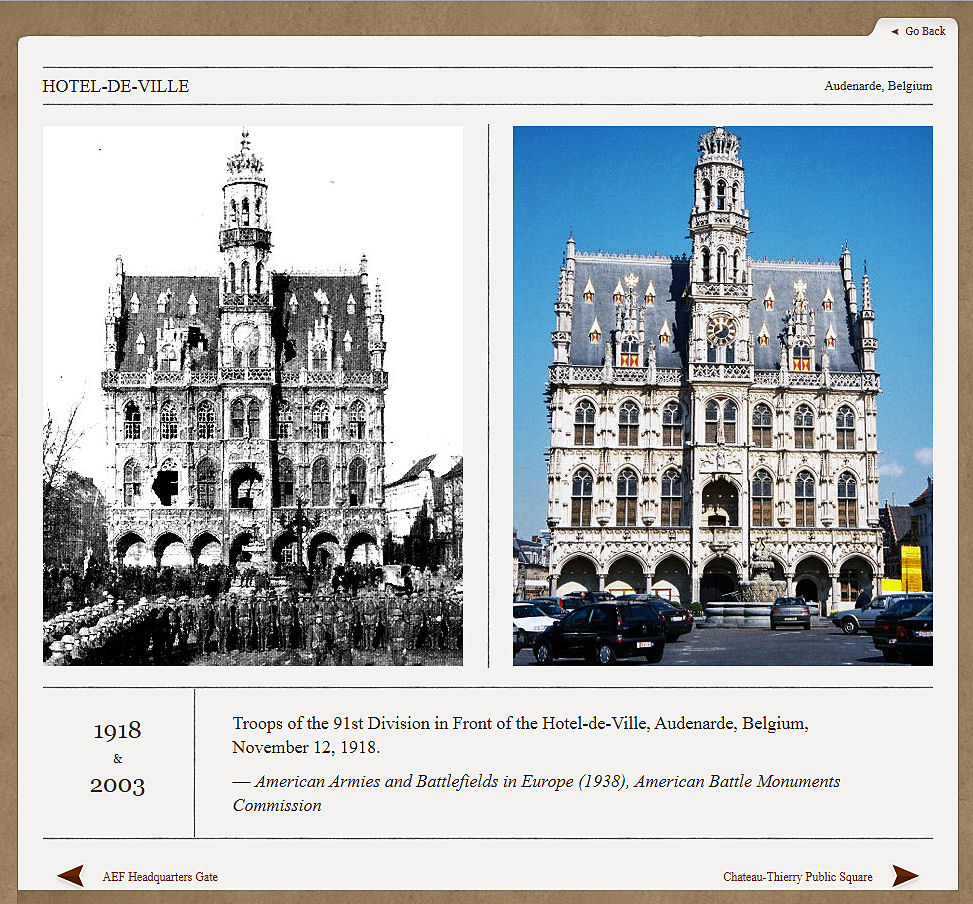

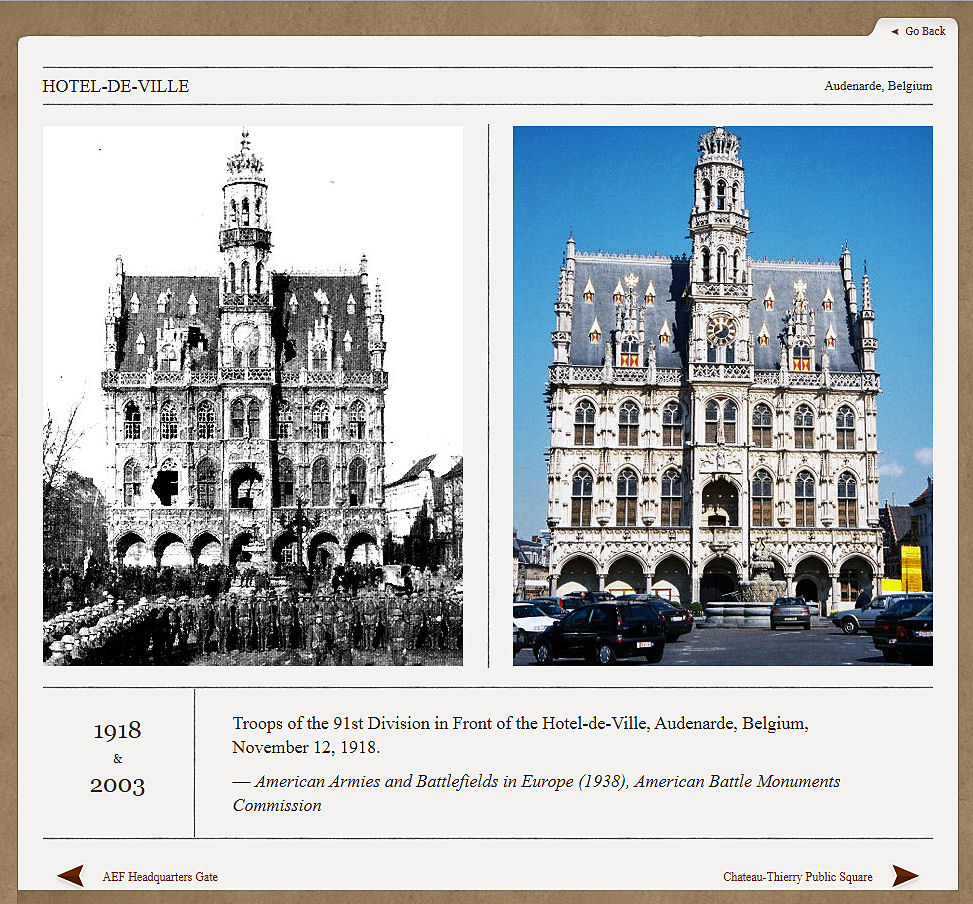

Then and Now: Hotel-de-Ville, Audenarde, Belgium

Western Front traveler Andy Pouncey's full website War Untold can be visited

HERE.

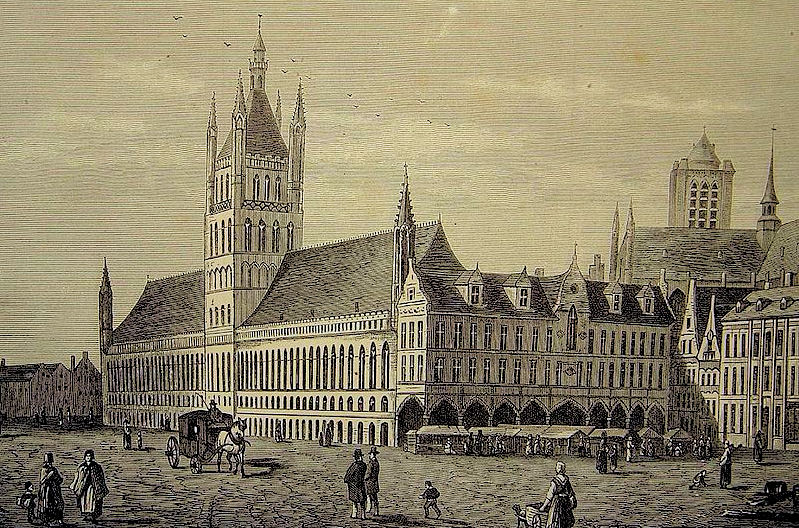

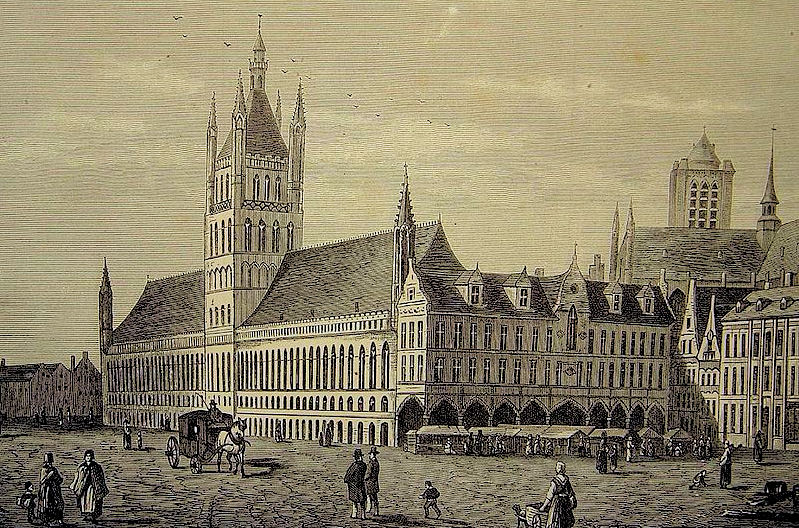

Restoring the Cloth Hall

Cloth Hall, 1872

The greatest cultural destruction from the war in Flanders was in

the leveling of Ypres. And the most visible treasure of the town

was its immense medieval Cloth Hall, built in the 13th and 14th

centuries. During the days when Ypres was a world leader in

the textile industry it served as the market place, warehousing,

and offices for what was then the cutting-edge new technology

and source of wealth.

The southern wing of the hall had a magnificent facade,

surmounted by a tall belfry in the center, its oldest element. The

foundation stone for the belfry (and watchtower) was laid by Baudouin IX, Count of Flanders. Over the centuries the Hall was frequently restored and embellished and in 1914 held many irreplaceable artistic masterpieces, frescoes, murals, tapestries, and painting. Many of these would be lost forever during the Great War.

Reduced to Rubble and the Stub of the Belfry

In early November German artillery units drew close enough to

begin shelling Ypres and a few random hits were made on the

Cloth Hall itself. The southeastern section of the Hall, a less

strongly built addition known as the Nieuwerk, constructed in

the 17th century, was the first feature to fall. Struck by German

artillery on 21 November 1914, its south gable was destroyed.

The following day the Cloth Hall burst into flames, destroying its

upper floors, and a few weeks later the Nieuwerk was

completely destroyed. Over the next four years, shells

relentlessly reduced the structure, although—oddly—just

enough of the belfry survived so that the Tommies marching

through the town always recognized the ruins.

With the necessity to focus on rebuilding the necessary infrastructure of Ypres, it took a full decade after the Armistice to initiate restoration of the Cloth Hall. Funding, local redevelopment priorities, architectural purity–would the design match the original or would contemporary styles be incorporated in the design–were all areas of great contention. The strategy to try to match the look and quality of the pre-1914 structure mostly prevailed and construction finally began in 1933 on the belfry. Eventually, despite the slow precise craftsmanship involved and the coming of another war that saw the town occupied by the enemy for five years, the project carried forward. The rebuilt Cloth Hall was dedicated in 1967, by my one-time acquaintance King Baudouin, grandson of Albert I, Belgium's greatest hero of the war.

The Cloth Hall Gloriously Restored

Today, the Cloth Hall is once again one of the world's cultural treasures and a premier tourist destination. It holds the town council and tourism offices, but most notably, the In Flanders Fields Museum, which our readers surely know, is one of the finest military museums anywhere and an unforgettable experience for visitors.

Sources: Michelin Ypres & the Battles of Ypres and Major and Mrs. Holt Ypres Salient Guides

Gas Attack in Flanders

Rare photo of a British gas barrage on Le Bizet Hamlet south of Ploegsteert on 7 September 1918. Despite the bombardment, German forces held the position until 3 October 1918.

|

100 Years Ago:

President Woodrow Wilson's Stroke

Returning Home from the Peace Conference, July 1919

President and Mrs. Wilson with Wounded Soldiers Aboard SS George Washington

Woodrow Wilson may have been one of our hardest-working chief executives and by the fall of 1919, he looked it. For most of the six months between late December 1918 and June 1919, our 28th president was in Europe negotiating the Treaty of Versailles and planning for the nascent League of Nations, efforts for which he was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize (an award he did not officially receive until 1920). Back home, however, the ratification of the treaty met with mixed public support and strong opposition from Republican senators, led by Henry Cabot Lodge (R-Mass.), as well as Irish Catholic Democrats. As the summer progressed, President Wilson worried that defeat was in the air.

Bone-tired but determined to wage peace, on 3 September 1919, Woodrow Wilson embarked on a national speaking tour across the United States so that he could make his case directly to the American people. For the next three and a half weeks, the president, his wife Edith Bolling Galt Wilson, assorted aides, servants, cooks, Secret Service men, and members of the press rode the rails. The presidential train car, quaintly named "Mayflower," served as a rolling White House. Also joining the party was the president’s personal physician, Cary T. Grayson, who had grave concerns over his patient’s health.

All during September of 1919, as the presidential train traveled across the Midwest, into the Great Plains states, over the Rockies into the Pacific Northwest and then down the West Coast before turning back east, the president became thinner, paler, and ever more frail. He lost his appetite, his asthma grew worse, and he complained of unrelenting headaches. Unfortunately, Woodrow Wilson refused to listen to his body.

Late on the evening of 25 September 1919, after speaking in Pueblo, Colorado, Edith discovered Woodrow in a profound state of illness; his facial muscles were twitching uncontrollably and he was experiencing severe nausea. Earlier in the day, he complained of a splitting headache. Six weeks after the event, Dr. Grayson told a journalist that he had noted a “curious drag or looseness at the left side of [Wilson’s] mouth – a sign of danger that could no longer be obscured.” In retrospect, this event may have been a transient ischemic attack (TIA), the medical term for a brief loss of blood flow to the brain, or “mini-stroke,” which can be a harbinger for a much worse cerebrovascular event to follow–in other words, a full-fledged stroke.

On 26 September, the president’s private secretary, Joseph Tumulty, announced that the rest of the speaking tour had been canceled because the president was suffering from “a nervous reaction in his digestive organs.” The Mayflower sped directly back to Washington’s Union Station. Upon arrival, on 28 September, the president appeared ill but was able to walk on his own accord through the station. He tipped his hat to awaiting crowd, shook the hands of a few of the people along the track’s platform, and was whisked away to the White House for an enforced period of rest and examination by a battery of doctors.

President Wilson Meeting with a Women's Group in San Francisco About Ten Days Before

the 25 September Episode

Everything changed on the morning of 2 October 1919. According to some accounts, the president awoke to find his left hand numb to sensation before falling into unconsciousness. In other versions, Wilson had his stroke on the way to the bathroom and fell to the floor with Edith dragging him back into bed. However those events transpired, immediately after the president’s collapse, Mrs. Wilson discretely phoned down to the White House chief usher, Ike Hoover, and told him to “please get Dr. Grayson, the president is very sick.”

Grayson quickly arrived. Ten minutes later, he emerged from the presidential bedroom and the doctor’s diagnosis was terrible: “My God, the president is paralyzed,” Grayson declared.

What would surprise most Americans today is how the entire affair, including Wilson’s extended illness and long-term disability, was shrouded in secrecy.

In recent years, the discovery of the presidential physicians’ clinical notes at the time of the illness confirm that the president’s stroke left him severely paralyzed on his left side and partially blind in his right eye, along with the emotional maelstroms that accompany any serious, life-threatening illness but especially one that attacks the brain. Only a few weeks after his stroke, Wilson suffered a urinary tract infection that threatened to kill him. Fortunately, the president’s body was strong enough to fight that infection off, but he also experienced another attack of influenza in January of 1920, which further damaged his health.

By February of 1920, news of the president’s stroke began to be reported in the press. Nevertheless, the full details of Woodrow Wilson’s disability and his wife’s management of his affairs were not entirely understood by the American public at the time. What remained problematic was that in 1919 there did not yet exist clear constitutional guidelines of what to do, in terms of the transfer of presidential power, when severe illness struck the chief executive. What the U.S. Constitution’s Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 on presidential succession does state is as follows:

In Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President, and the Congress may by Law provide for the Case of Removal, Death, Resignation or Inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what Officer shall then act as President, and such Officer shall act accordingly, until the Disability be removed, or a President shall be elected.

20 June 1920: First Post-Stroke Photo of

the President and First Lady

|

But Wilson, of course, was not dead and not willing to resign because of inability. As a result, Vice President Thomas Marshall refused to assume the presidency unless the Congress passed a resolution that the office was, in fact, vacant, and only after Mrs. Wilson and Dr. Grayson certified in writing, using the language spelled out by the Constitution, of the president’s “inability to discharge the powers and duties of the said office.” Such resolutions never came.

For the remainder of her life, Edith Wilson steadfastly insisted that her husband performed all of his presidential duties after his stroke. As she later declared in her 1938 autobiography, My Memoir:

So began my stewardship, I studied every paper, sent from the different Secretaries or Senators, and tried to digest and present in tabloid form the things that, despite my vigilance, had to go to the President. I, myself, never made a single decision regarding the disposition of public affairs. The only decision that was mine was what was important and what was not, and the very important decision of when to present matters to my husband.

Over the last century, historians have continued to dig into the proceedings of the Wilson administration and it has become clear that Edith Wilson acted as much more than a mere “steward.” She was, essentially, the nation’s chief executive until her husband’s second term concluded in March of 1921. Nearly three years later, Woodrow Wilson died in his Washington, DC, home, at 2340 S Street, NW, at 11:15 A.M. on Sunday, 3 February 1924.

Source: PBS News Hour, 2 October 2015, Dr. Howard Markel, Correspondent

|

New Memorial at Passchendaele

Maori Memorial at Zonnebeke, Belgium

Detail

|

An eight-meter-tall carved Maori monument was unveiled last Anzac Day (25 April) in Zonnebeke, Belgium, honoring the role of New Zealand's Maori and other service people in the First World War. During World War I, 2227 Maori served in the Maori Pioneer Battalion, of which 336 died on active service and 734 were wounded. Maori also served in other units and were among the 18,058 New Zealanders killed during the war.

The project was championed by Flanders local Freddy Declerck, former chairman of the Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917, who has long supported recognition for both the New Zealand and Australian Anzac contingents, each of which fought costly battles near the museum grounds. The "pou maumahara" was created at the New Zealand Maori Arts and Crafts Institute from 4,500-year-old native New Zealand timber by master carvers, led by James Rickard. The monument is located at the Passchendaele Memorial Gardens on the grounds of the Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917.

Maori Pioneers Building a Plank Road on the Western Front

Sources: The New Zealand Belgian Embassy and RNZ News Website

|

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications

|

Order Our

WWI Musical CD

Click on Image for Information

|

Shop at

Amazon.com

|

Order the Complete Collection

Over the Top Magazine

Click on Image for Information

|

A World War One Film Classic

On 7 June 1917 the Battle of Messines, waged just south of the town of Ypres, opened with the explosion of 19 massive mines. These enabled one of the most decisive Allied victories of the war prior to the 1918 victory campaign. The most northern of these mines were placed under an artificial mound known as Hill 60. Beneath Hill 60 is a dramatization of the challenges faced by the team of Australian tunnellers made caretakers of the explosives after they were set in place, up to their detonation.

The two great threats the Aussies face are water seepage and German counter-tunnellers who are on to them. As the day of the attack draws near the tension grows and the film swells from a well-done, but standard, war movie into a first-class, fasten-your-seat-belts thriller. Beneath Hill 60 scores A in the categories: Historical Authenticity, Visual Look and Effects, and Utterly Believable Characters (both Australian and German). The film is available at both Amazon and Netflix. Don't miss it!

|

|

Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

(Or send it to a friend)

(Or send it to a friend)

|

Design by Shannon Niel

Content © Michael E. Hanlon

|