October |

Access |

The Great War's Olympiad

|

||||||||

|

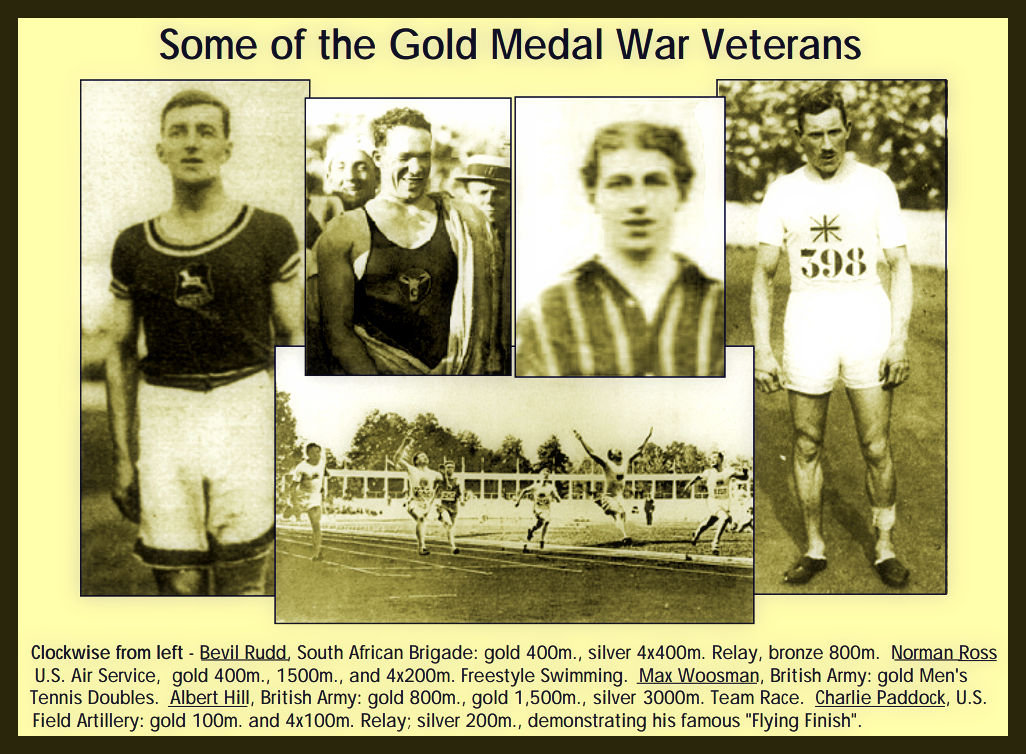

Consider this: Conspicuously placed outside the Olympic Stadium was a statue of a "competitor" executing a difficult athletic throw. The figure (shown here), however, is not an athlete, but a Belgian soldier. And, he is not launching a discus or a javelin, but a hand grenade. Many of the competitors and medal winners at Antwerp had seen combat during the war. A transitional event held the previous year prepared many of these warriors for their move from the battlefield to the arena. After the Armistice, the victorious Allied armies had millions of troops with nothing to do. In the spirit of keeping the men busy and out of trouble and to help them start the transition to civilian life, sports programs sprung up in all the military camps. By January 1919, arrangements were made for a competition in Paris modeled on the Olympics, hosted by American commander General John J. Pershing. Eighteen nations competed in these Inter-Allied Games. Sprinter Charlie Paddock and swimmer Norman Ross would be gold medalists at both Paris and Antwerp. Inter-Allied light heavyweight boxing champion Gene Tunney would later defeat Jack Dempsey for the world heavyweight championship. By one estimate, almost 10% of the competitors at Antwerp were veterans of these games. A year later, the athletes and the world were ready for the return of the Olympic spirit, but the war was not yet forgotten. MH

How Antwerp Got the Games

By Bert Govaerts

The International Olympic Committee at Their Last Prewar Meeting, Paris, 1914

On August 14th, 1920, King Albert I of Belgium,

wearing the uniform of supreme commander of the

Belgian Army, opened the VII Olympiad with

these words: "In reply to our invitation, athletes

from the four corners of the earth have gathered together

in Antwerp to celebrate with us the return of peace."

It had been a gamble for the Belgian Olympic

Committee and for the city of Antwerp to accept the

responsibility of organizing the Games in the

difficult years following the Great War. Their

actually fully taking place was something of a notable

accomplishment in itself. Financially the Games

of 1920 turned out to be an unmitigated disaster, but

sports historians agree that they were also a

landmark in Olympics history.

Antwerp had a long interest in hosting the games. By 1900 the city boasted a number of athletic

associations, fencing and tennis clubs, equestrian

facilities, etc. Soccer and cycling attracted larger,

mainly working-class crowds. Some of the leading

men of Antwerp's sporting life assisted at the 1912

Olympiad in Stockholm. They decided that the time

had come to put in a bid to organize the 1920

Games. The Olympic city for 1916 had already been

chosen. That was to be Berlin.

The Belgian bid to organize the 1920 Games was

sent to the International Olympic Committee (IOC)

on 9 August 1913. Three other cities were in the

race: Budapest, Amsterdam and Rome. No decision

had been taken by the time hostilities broke out in

August 1914. Like many other people at the time, the

IOC's patron, Baron de Coubertin, thought the war

would soon be over. For a while, he remained

convinced that the 1916 Games could be held in

Berlin as planned. But when the war dragged on, he

accepted there would be no games at all in 1916. The

IOC started looking forward to 1920.

German plans for dealing with Belgium proceeded as

planned. At Liège, the town was taken on 6 August, and

the major fortresses, which covered the Meuse

crossing, were shelled with newly arrived and specially

designed long-range Krupp 420mm siege howitzers on

the 12th, the final fort surrendering at 8:30 a.m. on the

16th. On the 19th, the Germans attacked the Namur

fortress, again with Krupp 420mm howitzers. By the

evening of the 23rd, five of the nine forts at Namur

were in ruins. At midnight, the survivors of the Belgian

garrison made their escape. Any major Belgian threat

to the German advance into France was no more.

Antwerp Occupied

In the first months of the Great War, "Poor Little

Belgium" became the focus of Allied propaganda–and for good reason. Around 5,500 Belgian civilians

were killed during the invasion in 1914, often as

victims of reprisals, hostage taking, and needless

cruelty by German soldiery and officers.

What about the war's impact on Antwerp? Besides being Belgium's

commercial capital, the city had always had a

military function as well. Three vast circles of forts

protected it, and it was within these walls that the

tiny Belgian Army was to seek refuge in the face of

overwhelming military force, to await aid from

friends or allies. However, to save his army, King Albert ordered its evacuation from the Antwerp Zone.

By 10 October the city and entire fortress area of

Antwerp were in German hands. The city had

suffered from heavy bombardment. Hundreds of

houses were destroyed, but the city would most

likely have been entirely razed to the ground (as

was later to happen to Ypres) had the Belgian Army

stayed within the fortified camp and been able to

hold the front lines with aid from reinforcements

from abroad. The media exposure

it had received at the beginning of the war (many

foreign reporters had come to the city in the weeks

leading up to the siege) was an "asset" in the

peaceful race to get the 1920 Games. As a "victim of

war," the city was deemed entitled to host the

Games as soon as the war was over. Of the prewar competitors, Amsterdam

was a "neutral" city, as was Rome, capital of then

still-neutral Italy, Budapest a "hostile," and so they were all out of the running.

But things didn't work out that smoothly. A fourth

contender presented itself: the French city of Lyon.

As soon as this became known, one of the members

of the Belgian Olympic Committee, Count de Baillet Latour, got in touch with the Belgian government-in-exile (which had set up headquarters in Le Havre,

just behind the front lines) and together they

confirmed the Belgian bid, admitting at the same

time that postwar conditions might turn out to be

daunting. In Baillet-Latour's own words (from a

letter to Coubertin, 23 dated May 23 1915):

It is true that once the invader has been forced back by

the victorious armies, the amount of work to be done will

be enormous(...) It may prove impossible to carry out the

proposed improvements to the stadium's surroundings,

but the ruins awaiting rebuilding will give the country

the stamp of glory. Along the route of the marathon race,

the graves will be a reminder of the heroes who fell for

their country, soldiers who died in combat, or civilians

who were executed, and when the winner will enter the

stadium it will be as if a hero from ancient times arrives

to announce the victory of Legality.

Baron Pierre de Coubertin in His Office

This bit of wartime pathos worked well: days after

Armistice Day, Baron de

Coubertin let the Belgian government know that he

had made up his mind. The 1920 games were to be

held in Antwerp, at least, if the Belgians were still

prepared to host them in their war-ridden country.

Some were but others weren't. It is easy to

understand that little was left of the enthusiasm of

1913. Postwar conditions were quite hard in a

country that had suffered four long years of

occupation and exploitation by the Germans. There

was more: during the war a minority group of

Flemish nationalists collaborated with the occupiers.

This was used as a pretext by the French-speaking

elite to suppress the demands of the majority of

Dutch-speaking Belgians. In other words: this was

no time for the Belgians to play games. The prime

minister himself had to call in some favors. The

Belgian Olympic Committee "more or less had its arm

twisted" by the politicians, and then, eventually, the

Belgian bid was reconfirmed, and on 5 April 1919,

Antwerp was officially selected as the location for

the Games of the VII Olympiad. There were

sixteen months left to prepare everything.

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

Different Perspectives

Here are some very informative sources about Antwerp, the war, and the 1920 Games

![]() A Brief History of Antwerp

A Brief History of Antwerp

![]() Sites to See in Antwerp

Sites to See in Antwerp

![]() Antwerp 1914

Antwerp 1914

![]() The German Occupation of Belgium

The German Occupation of Belgium

![]() The 1919 Inter-Allied Games

The 1919 Inter-Allied Games

![]() 100 Years: the Antwerp Olympic Games (One Hour Video)

100 Years: the Antwerp Olympic Games (One Hour Video)

![]() Official Results: Olympics of Antwerp,1920

Official Results: Olympics of Antwerp,1920

![]() Antwerp and the Olympic Flag (PDF)

Antwerp and the Olympic Flag (PDF)

![]() "Scandal of Schelde": The Olympic Football Finals at the 1920 Antwerp Olympics (PDF)

"Scandal of Schelde": The Olympic Football Finals at the 1920 Antwerp Olympics (PDF)

The Olympic Oath

We swear that we are taking part in the Olympic Games as

loyal competitors, observing the rules governing the

Games and anxious to show a spirit of chivalry for the

honor of our countries and the glory of our sport.

First Delivered by Belgian War Veteran Victor Boin at the Antwerp Games

The Olympic Flag

These five rings represent the five parts of the world now won over to the cause of Olympism and ready to accept its fecund rivalries. What is more, the six colors thus combined reproduce those of all nations without exception.

Pierre de Coubertin, Founder of the Olympic Movement (First flown at the Antwerp Games)

Olympian Casualties

Olympics historian Steve Harris has provided us a sampling of participants in earlier Olympics, who were

casualties in the Great War. A full list of Olympians killed in the war can be found HERE.

1900 Paris Games:

Underwater swimming gold medalist Charles Devendeville of France was killed near Reims in September 1914.

1904 St. Louis Games:

Captain Arthur Wear of the 356th Infantry, 89th Division, of the AEF, died during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. He had won a bronze medal in doubles tennis at the III Olympiad.

1908 London Games:

400-meter gold medalist Wyndham Halswelle,

Britain, who had also fought in the Boer War and

the only man in Olympic history to win on a

disqualification, was killed fighting in France in

1915.

Rowing, four-oared shell, gold medal team from

Magdalen College, Great Britain, two members,

Duncan McKinnon and Robert Somers-Smith, killed

in action.

1912 Stockholm Games:

400-meter silver medalist Hanns Braun of

Germany, killed in action.

1,500-meter gold medalist Arnold Nugent Strode Jackson of Great Britain, wounded three times and

in 1918 promoted to brigadier, the youngest

general in the British army.

5,000-meter silver medalist Jean Bouin of France

and bronze medalist George Hutson of Great

Britain, both killed in action, September 1914.

When Did the Games Begin?

When the Olympic Games began is not known. Their origin lay far back in the shadows of time. Several peoples of Greece claimed to have instituted such games, but those which in later times became famous were held at Olympia, a town of the small country of Elis, in the Peloponnesian peninsula. Here, in the fertile valley of the Alpheus, shut in by the Messenian hills and by Mount Cronion, was erected the ancient Stadion, and in its vicinity stood a great gymnasium, a palæstra (for wrestling and boxing exercises), a hippodrome (for the later chariot races), a council hall, and several temples, notably that of the Olympian Zeus, where the victors received the olive wreaths which were the highly valued prizes for the contests.

This temple held the famous colossal statue of Zeus, the noblest production of Greek art, and looked upon as one of the wonders of the world. It was the work of Phidias, the greatest of Grecian sculptors, and was a seated statue of gold and ivory, over forty feet in height. The throne of the king of the gods was mostly of ebony and ivory, inlaid with precious stones, and richly sculptured in relief. In the figure, the flesh was of ivory, the drapery of gold richly adorned with flowers and figures in enamel. The right hand of the god held aloft a figure of victory, the left hand rested on a sceptre, on which an eagle was perched, while an olive wreath crowned the head. On the countenance dwelt a calm and serious majesty which it needed the genius of a Phidias to produce, and which the visitors to the temple beheld with awe.

The Olympic festival, whose date of origin, as has been said, is unknown, was revived in the year 884 B.C., and continued until the year 394 A.D., when it was finally abolished, only to be revived at the city of Athens fifteen hundred years later. The games were celebrated after the completion of every fourth year, this four year period being called an "Olympiad," and used as the basis of the chronology of Greece, the first Olympiad dating from the revival of the games in 884 B.C.

These games at first lasted but a single day, but were extended until they occupied five days. Of these the first day was devoted to sacrifices, the three following days to the contests, and the last day to sacrifices, processions, and banquets. For a long period single foot-races satisfied the desires of the Eleans and their visitors. Then the double foot-race was added. Wrestling and other athletic exercises were introduced in the eighth century before Christ. Then followed boxing. This was a brutal and dangerous exercise, the combatants' hands being bound with heavy leather thongs which were made more rigid by pieces of metal. The four-horse chariot-race came later; afterwards the pancratium (wrestling and boxing, without the leaded thongs); boys' races and wrestling and boxing matches; foot-races in a full suit of armor; and in the fifth century, two-horse chariot-races. Nero, in the year 68 A.D., introduced musical contests, and the games were finally abolished by Theodosius, the Christian emperor, in the year 394 A.D.

Charles Morris, Historic Tales, vol 10: the Romance of Reality

Whose Games?

By Bert Govaerts

The first Olympic Games after the tragedy of the

Great War might have been a fine stage for global

reconciliation. But the war was won by some and

lost by others. These were to be the Games of the

winners (and the neutrals). Just as Antwerp had

been selected because it had suffered on the

winning side during the war, a number of nations

were excluded because they had fought on the

wrong side. The Olympic ideal was supposed to

be "above" all politics and the International

Olympic Committee had purposely settled down

in neutral Lausanne during the hostilities, but its

president, Baron de Coubertin (who, as a

Frenchman, had luckily enough found himself on

the correct side), had enough common sense to

understand that less than two years after the end

of the war, German or Austrian athletes would

not be welcomed with open arms in a country

that they had helped ruin. The former Central

Powers (or what was left of them) were not really

excluded. They were simply not invited to

participate in 1920. It would not be until the 1928

Olympics that Germany once again sent athletes

to the Games.

Gold Medal for Antwerp Champions

Neither was Bolshevik Russia

invited; not only was it considered a subversive

state advocating the spread of world revolution, but it

had also left the Allies in the lurch in 1918 by

signing a separate peace treaty with Germany and

Austria. Moreover, Bolshevik Russia was engaged

in warfare with the newly independent Polish

state, a state that was receiving military aid and

assistance from France. Coubertin found an

administrative trick that allowed this one-time

"exclusion" of Bolshevik Russia and of the former

Central Powers without mortgaging the future of

his Games.

Of course, on the "winning" side there would be

many absentees. Many sportsmen, including a

number of Olympic champions, had died or been

crippled at the front. After years of continued

slaughter of Europe's youth, the competition

between nations could hardly be fair. This had

already been demonstrated during the so-called

"Inter-Allied Games" of 1919, during which the

United States, latecomers in the Great War,

showed their athletic superiority. The neutral

countries as well were in a favorable position.

Anyway, the Games had to be taken up again.

Twenty-nine nations accepted the invitation to

participate. Among them were the newly independent

states of Estonia, Czechoslovakia, and Finland, created

in the aftermath of the Great War. Belgium, Canada,

France, Great Britain, Greece, India, Japan, New

Zealand, Portugal, South Africa, and the USA had all

been combatants during the war. Yugoslavia, Brazil,

and Monaco participated for the first time, though at

the time Yugoslavia was still known as the Kingdom

of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. New Zealand

participated independent of the Australians for the

first time.

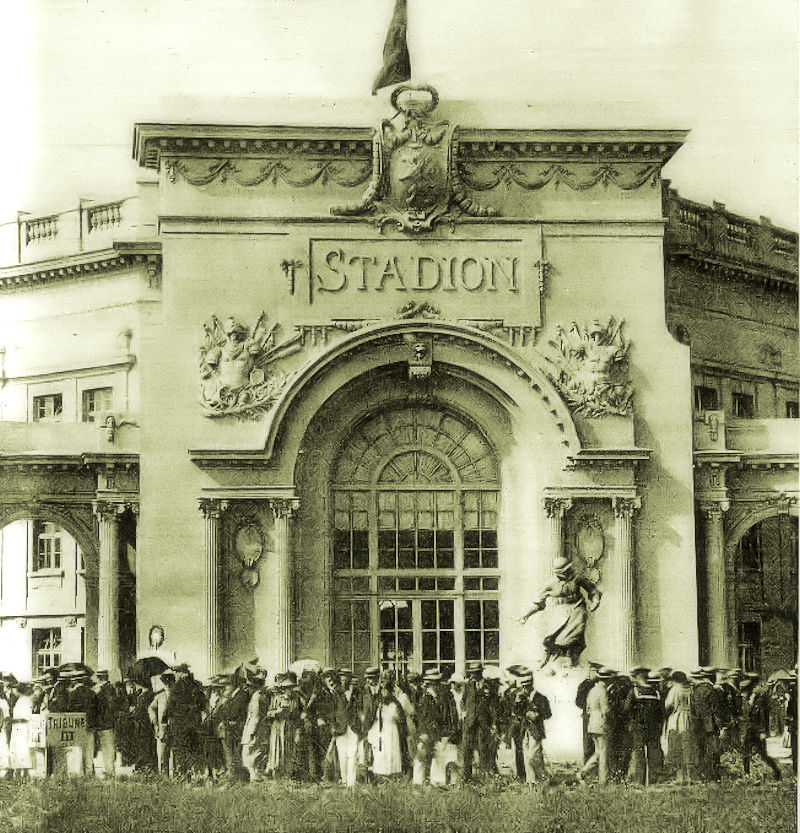

Stadium Entrance

It had been a top-level decision to go ahead with the

Games in Belgium. The "generals" had spoken, now

the sportive "soldiers" had to march once again. The

practical problems were forbidding. There was simply

nothing available, except the will (of some) to push

forward. Of course, money was the first major

problem. It was not just that the organizing committee

lacked funding. Belgium was then going through a

period of galloping inflation, which made it very

hard to calculate realistic budgets. And so much

remained to be done. There was no Olympic

Stadium, to mention just one obvious point. Some of

Belgium's sportive infrastructure survived

the war years, but the swimming pool, the tennis

lawns, the boxing and fencing arenas, etc. would all

have to be renovated and refurbished. Finding

accommodations for the athletes was another tricky

task in an impoverished country that was experiencing

a post-hostilities housing crisis. All this was solved in

one way or another, partly on borrowed money and

with a lot of improvisation "à la Belge."

The stadium was

finished in time, if only two months before the

opening of the Summer Games.

The most striking feature of the Olympic Stadium

was the "imperial," neo-classical entrance gate (a

temporary construction, made of cheap materials,

but few people knew that at the time). In front, a

statue by Albéric Collin was placed. Not of a classic

discus thrower, but of a Belgian soldier throwing a

hand grenade.

The accommodation problem proved harder to

solve. Some of the athletes would have to sleep in

city schools, others in military barracks. The poor

Dutch had to stay onboard a small vessel, the

Hollandia, which was moored at an Antwerp dock.

The 1920 Games were not exactly the most luxurious

or comfortable in history.

Local publicity for the Games suffered immensely

from a shortage of paper. A great poster campaign

was planned, but it was never realized. The official

poster for the summer games (one version shown above) was

designed by local artist Martha Van Kuyck. It

showed a classical discus thrower, more or less

wrapped in national banners and posing in front of

the Antwerp skyline, featuring the city's great pride,

the gothic spire of Our Lady's Cathedral. The poster

was not precisely a "state of the art" design. In fact,

it was very old fashioned, still breathing the

atmosphere of the Belle Époque, the period during

which the leading sportsmen of Antwerp had

started thinking of "their" Games. If anything, the

occupation had not really revolutionized their taste.

Anyway, local propaganda for the Games was so

lacking that when several prelude athletic events

were held, a Belgian newspaper wrote: "Friday

evening (April 23rd), at nine o'clock, the Olympic games

are supposed to begin. How many Antwerp citizens are

aware of this?"

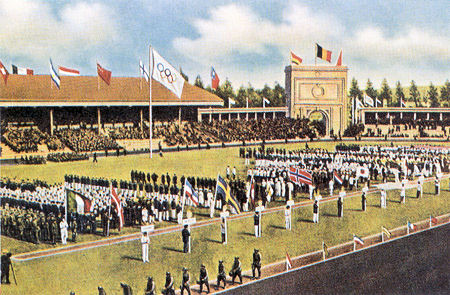

Opening Ceremony

The opening ceremony of the VII Olympiad took

place on 14 August 14 1920. It began with a religious

service in Antwerp's impressive gothic cathedral.

The entire Olympic family gathered in a Catholic

prayer house to listen to the admonishing words of

a cardinal of the Church. Many military delegates

from the Allied and neutral countries were present

as well, and the memory of the Great War was

omnipresent. The speaker, Cardinal Désiré Mercier,

Archbishop of Malines, belonged in part to the

national Belgian history of the war. During the

occupation he had taken an attitude of staunch

resistance toward the Germans, at times even

embarrassing the "neutral" Pope himself. Yet,

Mercier was not a universally popular hero in his

own country. The French-speaking Mercier

considered the Dutch language, spoken by the

Flemish, Belgium's majority community, as an

inferior tongue, fit only for everyday life but not for

use in science, politics, or diplomacy. His "Olympic"

speech (delivered after he had sung a de Profundis in

memory of the athletes who died during the war)

was entirely in French. That did not go unnoticed

outside the cathedral. It rankled the atmosphere

even before the Games began.

The speech itself clearly, be it obliquely, referred to

the Great War once again and not simply in

pacifying terms. Before 1914, the Games, the

Cardinal told the athletes, had been a preparation

for war. History proved the correctness of the

provisions of their founder. Today the Games were

preparation for peace but also...."against the terrible

risks that have not entirely disappeared from our

horizon." Mercier urged the athletes to be moderate,

disciplined, and prepared to accept authority. All

this in order to prevent sports becoming the "brutal,

haughty translation of the Nietzschean conception of life."

Germany wasn't mentioned by name, but everyone

understood the message.

After the religious ceremony, the Olympic family

moved to the stadium on the outskirts of the city.

After gun salutes were fired, King Albert, wearing

his military uniform, solemnly opened the 1920

Games. Just as nowadays, the delegations marched

in and paraded in front of the grandstand. When

everyone was in, the new five-ringed Olympic

banner was raised for the first time in history.

Belgian soldiers released white doves to celebrate

the return of peace. Another novelty followed: a

Belgian athlete, decorated wartime veteran, and prewar Olympic medalist Victor Boin stepped forward,

carrying a Belgian flag and flanked by two Belgian

officers. He was the first athlete ever to take the

Olympic oath. He did it, of course, in French.

And that was it. The Games could finally begin. The

press praised the quality of the ceremony but could

not fail to notice that the stadium was hardly filled

to capacity. In any case, the Antwerp Games had begun.

The Veteran's Big Presence at Antwerp

Joseph Guillemot (1899-1975), French winner of the 5,000-meter race, possibly best

embodied the transition from war to sports for the athletes at Antwerp. Born in Le Dorat,

France, Joseph Guillemot's lungs were severely damaged by mustard gas when he fought in

World War I. Also, his heart was located on the right side of his chest. Despite this, Guillemot,

an athlete of small stature (5'2", 118 lbs.), but with extraordinary vital capacity, won his

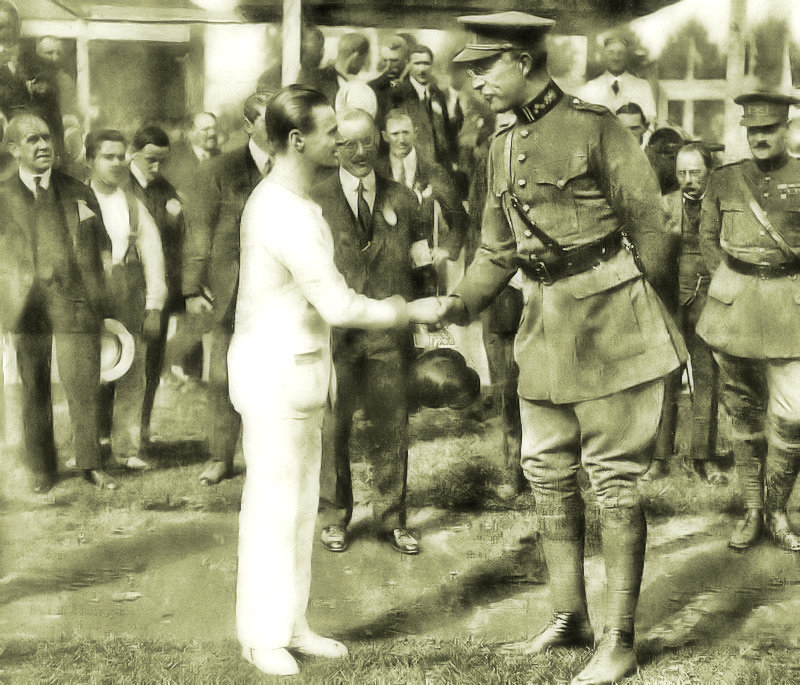

regiment's cross-country championships.  Joseph Guillemot Receiving the Congratulations of King Albert

After the Olympics, Guillemot won the International Cross-Country Championships in 1922

individually and led the French team to first place in 1922 and 1926. He won the French

Nationals in 5000 m. on three occasions but missed the next Olympics due to the

disagreements between him and the French Athletics Union. He also held two world records:

2,000-meter (5:34.8) and 3,000-meter (8:42.2). Joseph Guillemot, a pack-a-day cigarette

smoker, died in Paris at the age of 75.

|

The Athletes Get to Work

By Bert Govaerts

Start of the Marathon; Insert: Gold Medalist Hannes Kolehmainen of Finland

Despite many complaints about the practical

circumstances in which the 2,626 athletes had to

perform (some swimmers saw rats in the pool and the

oarsmen had the feeling they had been put away on

one of the ugliest canals of Europe, to mention just a

few complaints), the sportive agenda was comprehensive. All in all, 154 competitions were held in

different fields, ranging from athletics to arcane

types of archery. Some of the disciplines, like the

folkloristic "tug of war," were included for the last time

in the Olympic program. Soccer and rugby football

were both fully present, but only one rugby match

took place, in which the United States defeated France

for the Gold Medal.

Italy's Gold Medal Bicycle Team

If Olympic records are the standard for quality, the 1920 Games were a modest success. Fourteen new records were established: six in swimming (some of which were also world records), eight in athletics. Bad weather with heavy rains that damaged the new cinder track in the stadium was held responsible for some of the more disappointing results. The Games were dominated by the USA, whose athletes won the most medals. The finest performance was no doubt that of Finnish long-distance runner Paavo Nurmi, who won four medals: silver for the 5,000-meter, and gold for the 10,000-meter, and a double gold in cross-country (individual performance and with the Finnish team). Other legendary Olympians whose reputations emerged or were enhanced at Antwerp included Hawaiian swimmer Duke Kahanamoku, French tennis star Suzanne Lenglen, and the greatest fencer in Olympic history, Nedo Nadi of Italy, who won six gold medals in the games.

Finalists for the Women's 100-Meter Swim

Host Belgium's greatest moment at the games occurred in September when

their team (solid jerseys) won the football championship in a disputed 2-0

victory over Czechoslovakia. The 65,000

fans in and outside the stadium, who

stormed the field afterward, showed

little concern that the losing squad

felt that the referees were "homers".

Action in the Soccer Final, Concluding Event of the Antwerp Games

The VII Olympiad ended on 12 September 1920. Coubertin wrote very flatteringly: "The success of the Antwerp Olympic Games is beyond all expectations. In spite of political, economic and even meteorological conditions which were all against them, the VII Olympiad took place. . . with mastery, perfection, and dignity, in keeping with the strenuous and persevering efforts of the organizers."

Some weeks earlier Coubertin praised the

fighting spirit and resourcefulness of the Belgian

people, "qualities which have become apparent in

peace as they did in the 1914 war." So, the first Games

after the Great War had taken place, and the

Olympic ideal had survived. That is no doubt the

most important fact to be established about them.

As for the "perfection" of their execution,

opinions were divided. Some delegations kept on

nagging about amateurism issues and a lack of

coordination, which were supposed to explain

their disappointing results. The Parisian press was

very severe. One paper wrote: "What a pity that the

VII Olympiad was given to the city of Antwerp because it can be said, that no moral benefit has come from it." Some Flemish newspapers too found that

the elitist organizers had failed. They had

concentrated too much on their favorite

disciplines and neglected the popular sports.

Our principal contributor for this issue, Bert Govaerts (born 1952), is an Antwerp-based journalist. He was series editor for historical documentaries produced by the public television network of Flanders (Belgium) for many years. Under his supervision, a number of documentaries on World War I were produced for Belgian television. Also an author, with our contributing editor Tony Langley, he wrote an illustrated history of advertising during the war titled Kassa! Kassa! and is currently working on a series of biographies on notable Belgian citizens, of which two have been published.

100 Years Ago:

|

Capt. Frederick Banting, MC |

When the war ended in 1919, Banting returned to Canada and was for a short time a medical practitioner at London, Ontario. He studied orthopedic medicine and was, during the year 1919-1920, Resident Surgeon at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. From 1920 until 1921 he did part-time teaching in orthopedics at the University of Western Ontario in London besides his general practice.

Banting Performing Surgery on the Western Front

On 31 October 1920, Frederick Banting woke up at 2:00 in the morning in London, Ontario, and made note of his insight that would lead to the discovery of insulin as a treatment for diabetes. The evening before, Dr. Banting had read an article in the journal Surgery, Gynecology, and Obstetrics, titled "The relation of the islets of Langerhans to Diabetes with special reference to cases of Pancreatic Lithiasis" He wrote in his journal "Diabetus [sic] Ligate pancreatic ducts of dog. Keep dogs alive till acini degenerate leaving Islets. Try to isolate the internal secretion to relieve glycosurea." Later in the day, he called a colleague to explain his idea— that the way to isolate the theorized (but undiscovered) hormone within the pancreas that controlled blood sugar level would be to let the acinar cells secreted from the pancreas to wither, leaving the insulin. Fourteen months later, on 11 January 1922, Banting and his assistant Charles Best, would make the first human test of the extract. The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1923 was awarded jointly to Frederick Grant Banting and John James Rickard Macleod "for the discovery of insulin."

Sources: Wikipedia; Banting House

Banting insisted on serving in the Second World War just as he had served in the First. He was promoted from captain to the rank of major. His knighthood transformed his official title to “Major Sir Frederick Banting, MC.” Because of his research, the Canadian government would not allow him to serve on the front lines. However, they urged him to continue his involvement with the National Research Council of Canada. He worked on such diverse projects as treatments for mustard gas, anti-gravity suits and oxygen masks, and biological and chemical warfare.

In February 1941, Banting was given the opportunity to return to England for three weeks. He was sent to review wartime medical research in England, with the possibility of bringing some of this research back to Canada for protection. At 8:30 pm on 20 February 1941, he left with a crew of three on Hudson Bomber Flight T-9449. Approximately half an hour later, the oil cooler failed, leading to the failure of both engines and the radio. The pilot, Captain Mackey, attempted to land the plane on Seven Mile Pond, Newfoundland (eventually renamed Banting Lake). The aircraft clipped the trees and was brought down only metres away from a potentially safe landing place. Two of the crew died upon impact; Banting and Mackey survived. In a last act of service, he managed to

wrap and treat the injuries of the pilot, allowing Mackey to leave the crash site to get help. Banting, wounded and delirious, wandered away from the plane and died of exposure. He was buried in Toronto’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

As a Researcher Between the Wars

Remembering Those "Lost Battalion" Aviators

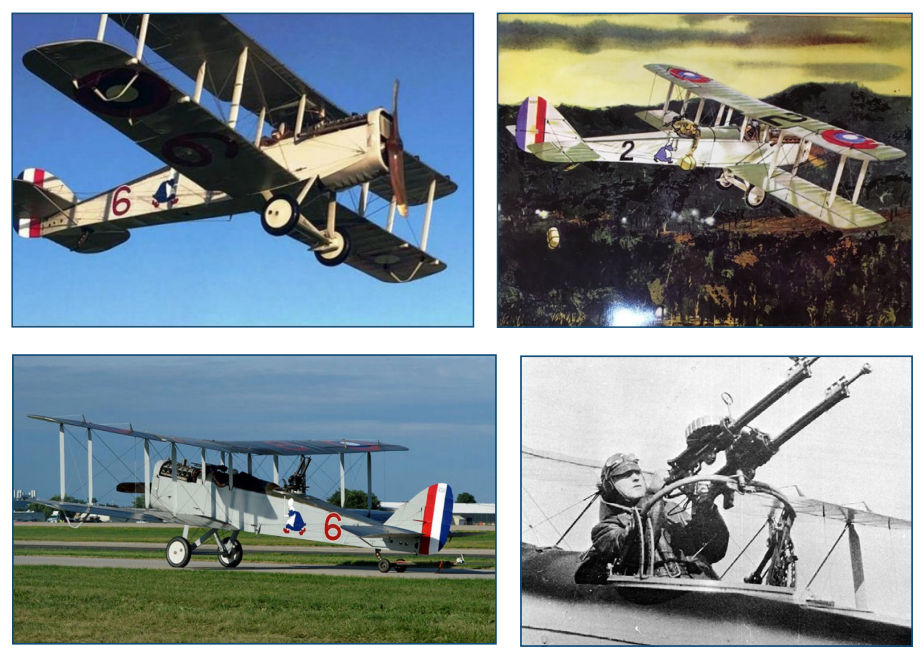

Images of Medal of Honor Mission DH-4 and Observer/Gunner Lt. Erwin Bleckley

One of the interesting developments during the post-WWI Centennial period is a convergence of interest in the aerial effort to support the surrounded Lost Battalion of the Meuse-Argonne battle and honor the two aviators, Lieutenants Erwin Bleckley and Harold Goettler, who were killed in that effort and later awarded the Medal of Honor, posthumously. Their service, truly, was "above and beyond the call of duty." Here's one description of the mission:

On 6 Oct 1918, during the first search for the Lost Batallion, [Pilot] Goettler and [Observer/Gunner] Bleckley thought they had captured a glimpse of the unit. The mission was a terrifying ordeal, and their original aircraft had been grounded upon returning due to damage from heavy enemy fire. Nevertheless, they volunteered for a second, riskier mission using a borrowed DH-4. That mission was to locate, map, and resupply the besieged American soldiers. Their strategy: fly lower and slower to purposely attract enemy fire to pinpoint the missing unit’s position. Tragically, both men died in the attempt.

Lt. Harold Goettler |

Apparently independent of these efforts, the U.S. Air Force is honoring the two Medal of Honor recipients. Goettler's and Bleckley's original unit, the 50th Aero Squadron, is still operational. Now known as the 50th Attack Squadron. They operate the MQ-9 Reaper drones from Shaw, AFB, SC. In October, the Squadron Commander will be hosting an event to commemorate the Lost Battalion mission of their founding members. Unfortunately, because of Wuhan Flu restrictions, it will not be open to the public. However, readers of the Trip-Wire are encouraged on 6 October, the 102nd anniversary of the mission, to fill a glass of your favorite adult beverage, and hoist it to the memory of two American heroes, Lieutenants Erwin Bleckley and Harold Goettler.

Thanks to Jerry Hester and Lt. Nick Jewell, 50th Attack Squadron, for much of the information and illustrations provided here.

The New Insignia of the 50th Attack Squadron with DH-4

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications |

||

Order Our

|

Shop at |

Order the Complete Collection

|

A World War One Film Classic

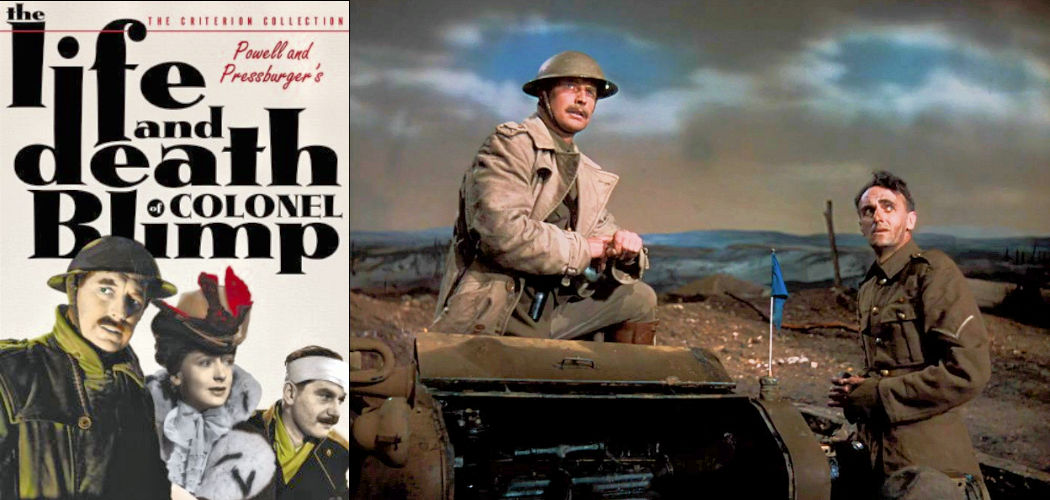

On the list of 100 Greatest British Films is a mid-WWII production that sounds like it's a satire of some sort, based on a figure used by cartoonists to personify everything ill-informed, and insufferable about the uppercrust. However, the central character of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, Clive Candy, is everything admirable a soldier, a friend, lover, and yes, a British gentleman, should be.

We meet Candy, played by Roger Livesey, in the midst of the Second World War, when he is commanding general of a troop of Home Guardsmen, who have no appreciation for the experience and knowledge their portly leader has gained in the Boer War and, most importantly, the Great War. The film mostly involves flashbacks to his earlier career, when he served on the battlefields with distinction, enjoyed/suffered three different romances (his love interests are all played by Deborah Kerr), and benefited mightily from the longtime friendship of a Prussian officer.

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is more a character study than a war film. In his review, I thought Roger Ebert put it best, "The movie looks past the fat, bald military man with the walrus mustache and sees inside, to an idealist and a romantic. To know him is to love him." You might read somewhere that Winston Churchill tried to scuttle the film. That's true, I believe. Winston was dead wrong, though, this film is a pro-British classic. Available on Netflix and Amazon MH

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon