November

2019 |

|

|

|

Celebrating Our

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive

101 Years Ago the Greatest Battle America Had Ever Fought Ended

Photo: 78th Division North of the Argonne Forest, October 1918

Looking Back 17 Years

If you had asked me 17 years (and 180 issues) ago, whether I would still be producing the St. Mihiel Trip-Wire in the year 2019, I probably would have been very skeptical and laughed out loud at the very thought. First of all, I would have thought my readers would have long moved on to other interests, or just become flat bored with the tales of the Great War. However, the subscriber list–from a peak of about 3,400–has stabilized at about 2,600 and the traffic of drop-in visitors each month via Internet browsers and folks who just don't like to share their emails has grown to at least ten times that number. So, I've still got a substantial and growing readership. Second, 17 year ago, I might have thought I would have become bored myself with the First World War and the surrounding events. But, lo and behold, I still find my favorite historical interest endlessly fascinating. So, with the audience I have, and my unflagging enthusiasm, you can count on seeing new issues of the Trip-Wire for the foreseeable future. Also–yes, another shoe is about to drop–you will still get my gentle reminders that, though the Trip-Wire and my daily blog Roads to the Great War are free to my readers, they are not free to produce. If you would like more information on how you can help, just look below just above this month's WWI Film Classic. Now please read on to learn a lot about the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and check in on our regular stuff. Onward! MH

Meuse-Argonne Primer

Quick Facts

Where: Northwest and North of Verdun

When: 26 September 1918–11 November 1918

Allied Units Participating: U.S. First Army, commanded by General John J. Pershing until 16 October, then by Lt. General Hunter Liggett. Three U.S. corps plus one French corps; 23 American rotating divisions were involved plus specialized units assigned to the Corps and Army commands.

German Forces: Approximately 40 German divisions from the Army Groups of the Crown Prince and General Max Carl von Gallwitz participated in the battle, with the largest contribution by the Fifth Army of Group Gallwitz commanded by General Georg von der Marwitz.

Memorable for:

The Largest battle in American history by casualties and ground forces involved.

Learning ground for the American military for the rest of the 20th century. Numerous future Army Chiefs of Staff and Marine Corps Commandants participated in the battle.

Gave America its largest European military cemetery.

Source of many legends and traditions, including the Lost Battalion, Sgt. York, Balloon Buster Frank Luke.

Operations, 26 September – 31 October 1918:

The area between the Meuse River and the Argonne Forest was chosen for the U.S. First Army’s greatest offensive of the war because it was the portion of the German front which the enemy could least afford to lose. The lateral communications between German forces east and west of the Meuse were in that area and they were heavily dependent upon two rail lines that converged in the vicinity of Sedan and lay within 35 miles of the battle line. The nature of the Meuse-Argonne terrain made it ideal for defense. To protect this vitally important area, the enemy had established almost continuous defensive positions for a depth of 10 to 12 miles to the rear of the front lines. The movement of American troops and materiel into position the night of 25–26 September 1918 for the Meuse-Argonne attack was made entirely under the cover of darkness. On most of the front, French soldiers remained in the outpost positions until the very last moment in order to keep the enemy from learning of the large American concentration. Altogether, about 220,000 Allied soldiers were withdrawn from the area and 600,000 American soldiers brought into position without the knowledge of the enemy.

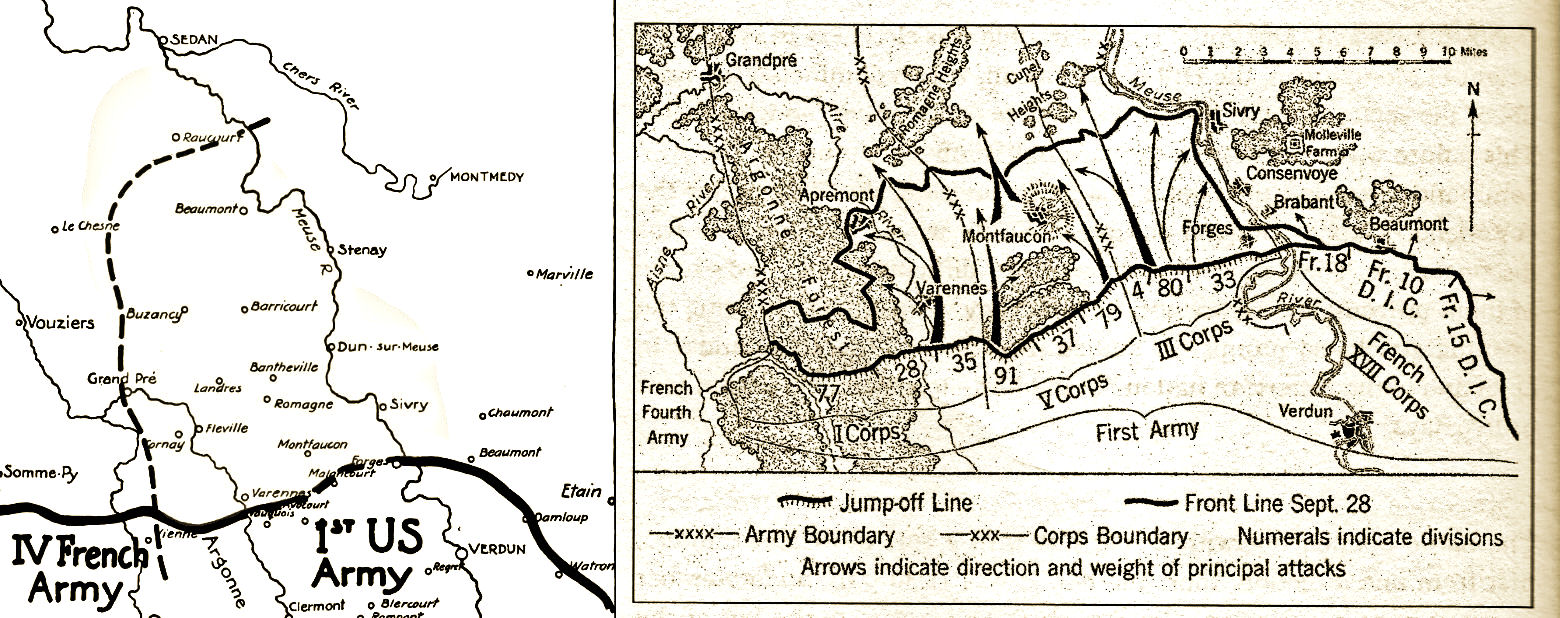

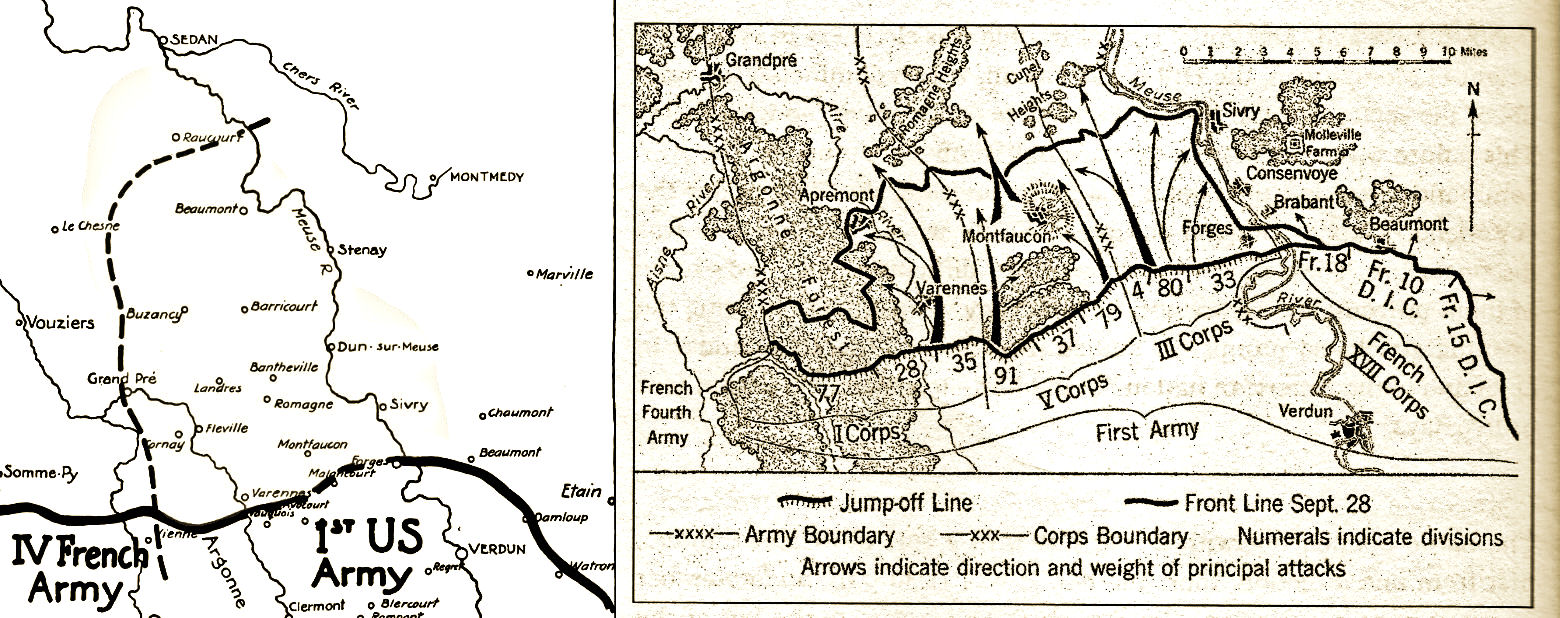

The Full Battlefield & the Opening Assault

Right Click Open Image in New Tab for Larger View

Following a three-hour bombardment with 2,700 field pieces, the U.S. First Army jumped off at 0530 hours on 26 September. On the left, I Corps penetrated the Argonne Forest and advanced along the valley of the Aire River. In the center, V Corps advanced to the west of Montfaucon but was held up temporarily in front of the hill. On the right, III Corps drove forward to the east of Montfaucon and a mile beyond. About noon the following day, Montfaucon was captured as the advance continued. Although complete surprise had been achieved, the enemy soon was stubbornly contesting every foot of terrain. Profiting from the temporary holdup in front of Montfaucon, the Germans poured reinforcements into the area. By 30 September, the U.S. First Army had driven the enemy back as far as six miles in some places, but the advance was bogged down due to inexperienced units and commanders, poor logistics due to a lack of transport and non-existent roads, and a lack of coordination between artillery and infantry.

The Last Days of the War

October proved to be the costliest month of the war for the AEF. The Argonne Forest was cleared, the strongest positions of the multi-layered Hindenburg Line across the central Romagne and Cunel Heights were broken, the Meuse River was crossed in force, and the Meuse Heights on First Army's right flank were invested.

Yet, First Army had to learn better and lest costly methods while continuing the attack if it was to succeed in the fuller mission. General Pershing brought in experienced divisions and more combat engineers and eventually appointed his best senior general, Hunter Liggett, to command First Army. George Marshall was given the job of operations officer and new corps commanders were brought in. A new approach for a renewed general offensive was speedily prepared.

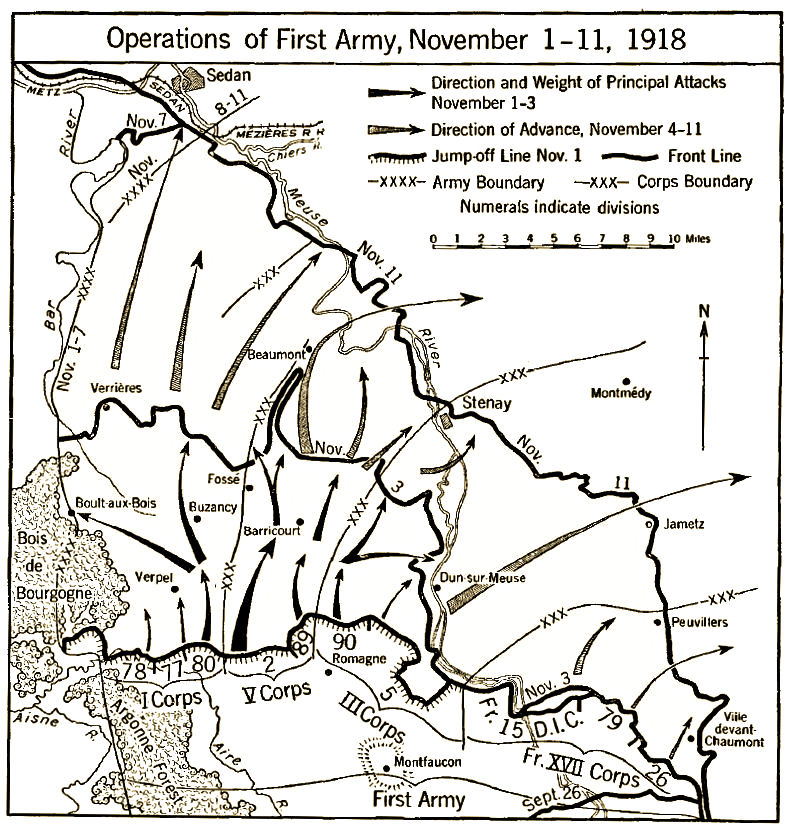

The final chapter of the great offensive by the U.S. First Army began at daybreak on 1 November after a two-hour concentrated artillery preparation. It would be the most important and successful American operation of the Great War.

The key roles in the assault were played by the III and V U.S. Corps, commanded by two future Army chiefs-of-staff, John Hines and Charles Summerall, respectively. They were supported by more artillery than had ever been assembled by the United States military. Tactics emphasizing mobility and better re-supply techniques to support a rapid advance were implemented. For the first time, the AEF aggressively used gas warfare to its advantage. The lessons of the earlier battles had been absorbed and corrections made. Probably the most significant innovation made in the final attack was the massive, overpowering rolling barrage that incorporated both heavy and light artillery. The attack on November 1 was the first to incorporate the heavy guns into a comprehensive fire plan for infantry support.

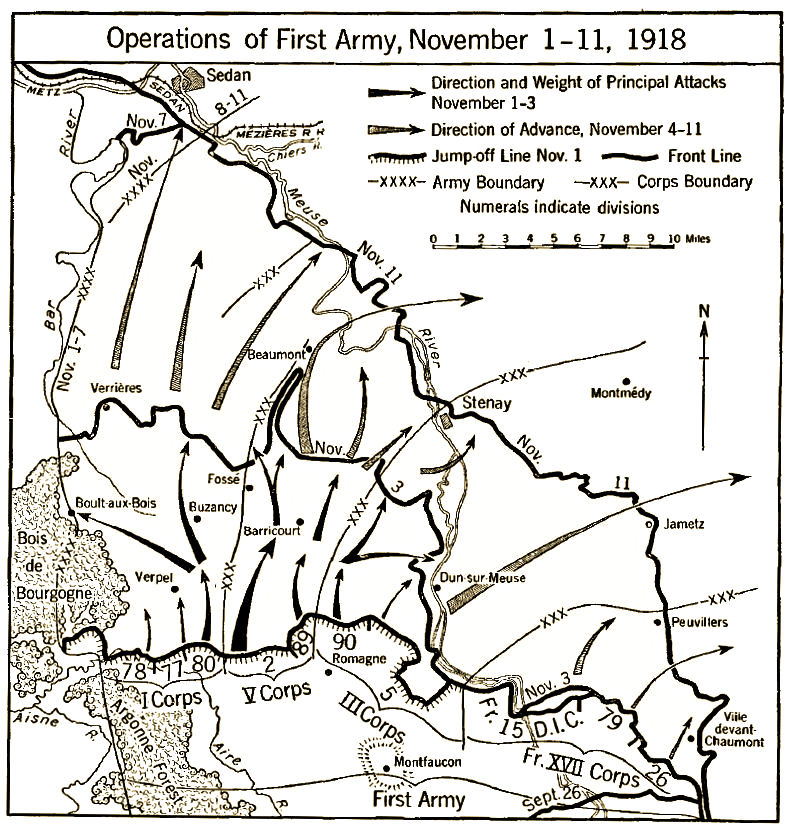

End Game of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, Note: Units on Right Shifting Axis Eastward

Right Click Open Image in New Tab for Larger View

Operations 1-11 November 1918:

By early afternoon of that first day the formidable last Hindenburg Line position on Barricourt Heights had been captured, ensuring success of the whole operation. That night the enemy issued orders to withdraw west of the Meuse and the battle turned into a rout, sometimes with U.S. forces racing north faster than the retreating Germans. By 4 November, after an additional crossing of the Meuse by the U.S. First Army, the enemy was in full retreat on both sides of the river. Three days later, when the heights overlooking the city of Sedan were taken, the U.S. First Army gained domination over the German railroad communications there, ensuring early termination of the war. The main objective of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive had been achieved. The U.S. military had learned the lesson that superior firepower, movement, and logistical support, rather than the blood of its soldiers, would be the key to victory in the 20th century.

Attention was shifting to the next U.S. strategic objective, Metz to the northeast, as the entire First Army began shifting their axis of attack in that direction. Meanwhile, the Second U.S. Army was renewing action down on the temporarily quiet St. Mihiel Sector. The Armistice ensued, however, before further major offensives could be mounted.

Sources: ABMC, Doughboy Center Website, Over the Top, September 2008

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

|

|

The Meuse-Argonne Challenge

Distressingly heavy casualties, disorganized and only partially trained troops, supply problems of every character due to the devastated zone so rapidly crossed, inclement and cold weather, as well as stubborn resistance by the enemy on one of the strongest positions on the Western Front.

Col. Geo. Marshall, First Army HQ

The Montfaucon American Monument consists of a massive granite Doric column, surmounted by a statue symbolic of liberty, which towers more than 200 feet above the war ruins of the former village. It commemorates the American victory during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

General George Marshall on St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne (PDF)

General George Marshall on St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne (PDF)

Army Heritage Meuse-Argonne Overview (PDF)

Army Heritage Meuse-Argonne Overview (PDF)

U.S. Army Meuse-Argonne Campaign History (PDF)

U.S. Army Meuse-Argonne Campaign History (PDF)

Marines to the Meuse (PDF)

Marines to the Meuse (PDF)

Stragglers: Disappearing Doughboys (PDF)

Stragglers: Disappearing Doughboys (PDF)

The Battle of the Meuse-Argonne, 1918: Harbinger of American Great Power on the European Continent?

The Battle of the Meuse-Argonne, 1918: Harbinger of American Great Power on the European Continent?

The Night Before the Launching of the Great Offensive

The Night Before the Launching of the Great Offensive

Memorials on the Meuse-Argonne Battlefield

Memorials on the Meuse-Argonne Battlefield

The History of the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery

The History of the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery

The Big Show

...After a tiresome, weary march through shelled road, devastated villages and destroyed forests, we advanced to the Argonne Forest, arriving and relieving the French at about three in the morning of September 26, 1918.

...Boy! Oh boy! What a beautiful sight just about dawn. It was light enough so that you could see for a hundred yards or so and stretched along was our first wave as straight as possible, skirmish formation advancing steadily as if we were on parade. Sergeants led about 10 paces ahead and spaced every 20 feet, lieutenants and captains a few paces more advanced with their automatic pistols in one hand and pistols in the other.

Sgt. Joe Rizzi, 110th Engineers

Memoir

Yesterday evening I started out with Captain Driscoll & Lt. Evans to set up an advance post -- but we found the former no man's land absolutely impassible except for foot and horseback, -- so we couldn't carry our equipment up. Roads were filled with supply and munitions trains which had the right of way.

Sgt. Sidney Adams, 91st Division

Unpublished manuscript

On October 15th, 1918, we were charging machine guns and men were being cut down like grass all around me. Then I was hit and fell, and couldn't get up. I laid there on the battlefield for three days and was assumed dead. Some man came by and said: Fields, what the hell are you doing laying there? The man picked him up, put him on his shoulder, and carried him three miles to the aid station.

Gangrene had already set-up, and they amputated my leg just below the knee. I was passing in and out of consciousness during the whole time and never recognized the man that carried me to safety. How he recognized me I'll never know because I was unshaven and was a mess. I've always regretted never knowing the man that saved my life.

Pvt. Clifton R. Fields, 32nd Division

Interview

While we were getting ready to take our wounded man to the rear, a runner appeared with the official news that an Armistice had been signed. Most everybody let out a few healthy yells, but I did not. For one reason, didn't feel much like yelling. I had some difficulty getting three more fellows to help me carry the stretcher.

Pvt. Clarence Richmond, 5th Marines, 2nd Division

Diary

First Army Strength During the Meuse-Argonne Offensive?

First Army on the Move

I've often seen comments to the effect that 1.2 million Americans fought in the great offensive. However, I've never seen those numbers substantiated or broken down. At the Hoover Institution archives there is a First Army report that gives these figures. "The strength of the U.S. First Army varied somewhat during

the Meuse-Argonne Offensive."

The First Army official report

cites the peak strength in early October as "896,000 American

and 135,000 French, [who were] deployed on the east side of the Meuse." However, there were fresh divisions being rotated in during October, and other units like pioneer infantrymen and coastal artillery were pulled in, so, as an aggregate figure the 1.2 million Americans in the battle, rings true. I just have never found an official accounting that shows that figure.

Obstacle Course

The first obstacle was the country itself. The forest was 10 miles of jungle growth,

rocky slopes, cliffs, ravines, innumerable brooks, its terrain shell-holed like the

moon.

The course of the Aire River, twisting north till it turned left to join the Aisne after it

outflanked the Argonne Forest below Grandpré, was just as difficult as the

forest, with the extra hazard of open spaces offering no cover to the attackers.

In addition, the Germans had had four years to prepare defenses, and they had

gone at it with Teutonic thoroughness.

The First Position was mainly barbed

wire and sacrificial machine gun units. Three miles behind it was the

Intermediate Position, cannoned and fortified in depth. . .

Behind this outlying complex was the first of the three main Hindenburg

barriers–the Giselher Stellung with the hill of Montfaucon at the grim center of

a promontory. . . Behind Montfaucon, five miles to the rear were the whalebacks

of the Romagne Heights—the second great barrier, the Kriegmhild Stellung,

storngest natural line in France. Five miles back of those heights were the the

bristling eminences around Buzancy, the last ditch barrier, the Freya Stellung.

From: The Doughboys, Laurence Stallings

National WWI Museum 2019 Symposium

1919: Peace?

When: 1-2 November 2019

Where: Kansas City, MO

Details:

HERE.

Mid Atlantic, League of WWI Aviation Historians

Chapter Meeting

When: 23 November 2019

Where: Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, near Dulles International Airport

Details:

HERE.

Within the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial in France, which covers 130.5 acres, rest the largest number of our military dead in Europe, a total of 14,246. Most of those buried here lost their lives during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive of World War I.

|

|

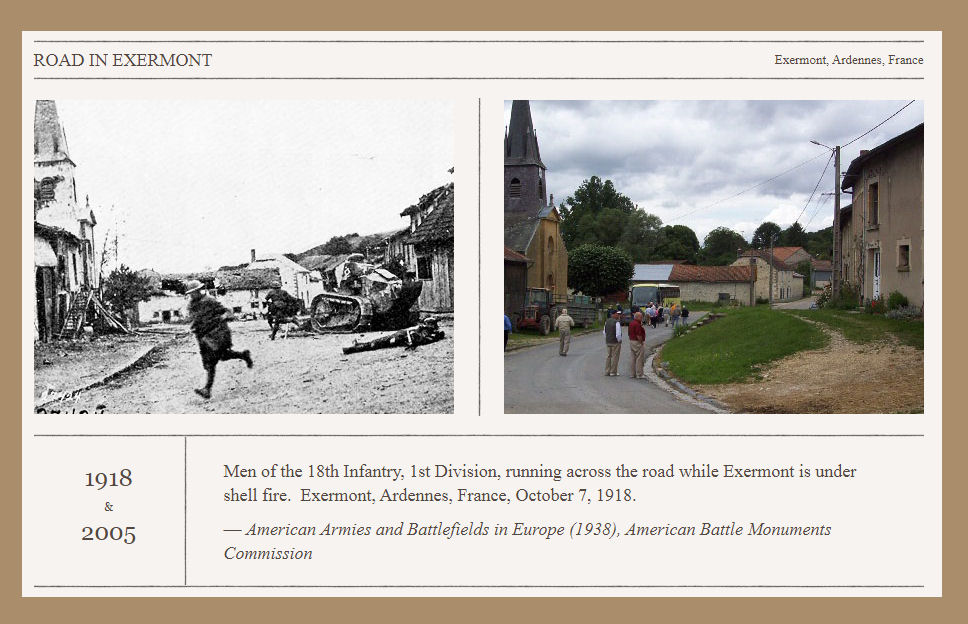

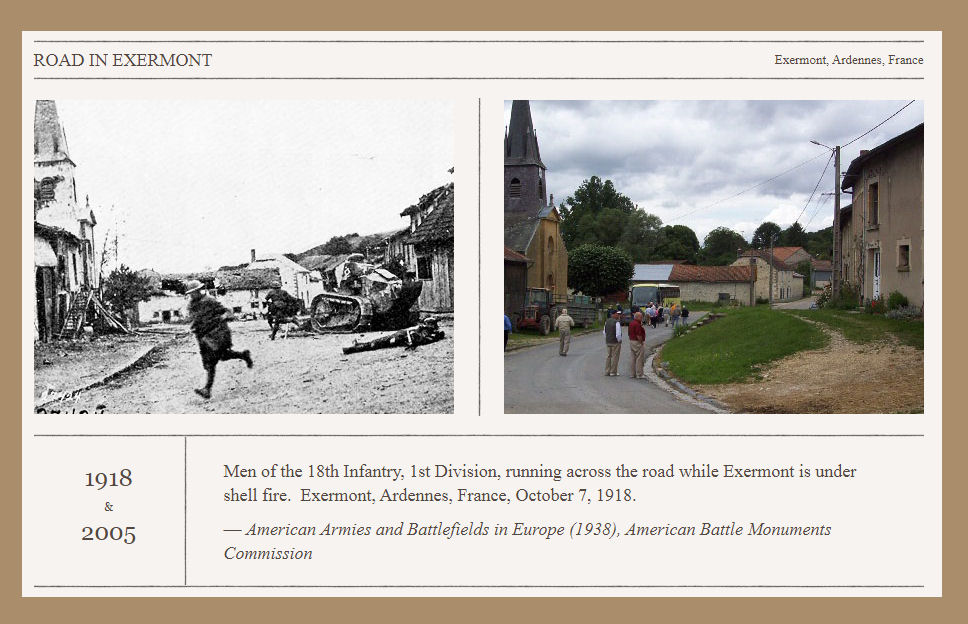

Then and Now: Exermont in the Argonne

Western Front traveler Andy Pouncey's full website War Untold can be visited

HERE.

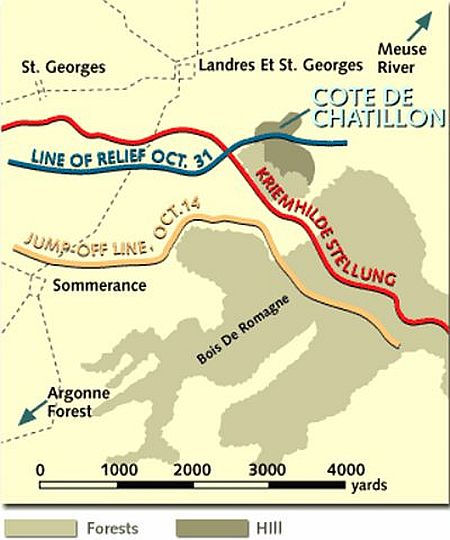

Côte de Châtillon:

The Meuse-Argonne Experience in Microcosm

Highly fortified Côte de Châtillon was a formidable obstacle to the advance of Pershing's First Army in the middle of October 1918. Its capture was a critical success for the AEF and is one of dozens of possible examples of the intensity of the fighting during the 47-day campaign. III Corps commander Lt. General Robert Bullard described the defenses in this sector:

The way out is forward, through the Kriemhilde Stellung, eastern section of the Hindenburg Line.... Not a line, a net, four kilometers deep. Wire, interlaced, knee-high, in grass. Wire, tangled devilishly in forests.... Pill boxes, in succession, one covering another. No 'fox hole' cover for gunners here, but concrete, masonry. Bits of trenches. More wire. A few light guns.... Defense in depth. Eventually, the main trenches. Many of them, in baffling irregularity, so that the attacker cannot know when he has mopped up.... Farther back, again defense in depth, a wide band of artillery emplacements.

The centerpiece of this system, the Côte de Châtillon, was eventually captured by the 84th Brigade (mostly Alabama and Iowa troops) of the 42nd Rainbow Division. The brigade's commander was none other than Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur, and his personal legend is deeply intertwined with the details and historical record of the fighting. A contemporary news account summarized both the operation and MacArthur's decoration for his leadership.

Barbed Wire Defenses of the Hindenburg Line,

Côte de Châtillon in the Distance

John Edwin Nevin

International News Service:

WASHINGTON, Nov. 18

Brig. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, former Washington press censor, has been cited again. He now has the right to wear, in addition to the French war cross given him while serving as chief of staff for the Rainbow division, the distinguished service cross of the United States army, decorated with a bronze oak leaf as an indication that he won the coveted decoration a second time. Incidentally, according to a personal letter reaching here today. "Gen. MacArthur has been wounded again, although he since fully recovered and is back leading the 84th brigade of the 42nd division into Germany toward the Rhine."

Heights Strongly Fortified

MacArthur received his latest citation for gallantry in leading his brigade at the taking of the Côte de Châtillon and hills 288 and 232. The first account of this operation of the world-famed Rainbow division as received here, says:

The Côte de Châtillon is 820 feet high and it dominated that part of the Kriemhilde Stellung which ran in front of [the villages of St. Georges and] Landres-St-Georges. The Americans on Wednesday, Oct. 15. attempted its capture. Traversing Its slopes yard by yard, they found that the Germans had constructed a machine gun fortress on the heights and every minute of 40 hours spent there the troops were exposed to a merciless rain of lead from all sides. A 77 gun, ensconced on the summit of the height, also poured down its deadly messages. Slowly the Americans, cradling on their stomachs, faced a massed fire of machine guns and rifles which was accompanied by shrapnel and hand grenades.

Faced Deadly Fire

Thomas Neibaur, 167th Inf.

Received

the Medal of Honor for

the Action

|

It was deadly work, trees all wired together made an almost Impossible barrier and volunteers had to face the fire to cut lanes through this belt of wire. It was decided, however, to bring up Stokes mortars. Through the mud and rain the Americans dragged them up to their positions and turned them on the Germans, Several of the enemy surrendered but a majority fought on. Hour after hour went by and brought no cessation of the merciless struggle. Yard after yard the Americans gained, stopping not for the darkness of the night. At last the greater part of the slopes was gained. The wire had been penetrated. Out came the bayonet, and with a wild hurrah the Americans fell upon the enemy. But these Germans were brave men. Standing beside their guns they fought to the last, dying where they stood. Finally the hill was the Doughboys, the 77-gun a prize, and the German garrison, except for a few prisoners, wiped out completely. It was a glorious victory.

Many histories of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive include an anecdote that runs something like this. Corps commander Charles Summerall in a meeting with MacArthur says, "Give me Chatillon or a list of 5,000 casualties," to which MacArthur was said to quickly respond, "All right general; we will take it or my name will head the list." MacArthur's dedication to the mission shows up in other accounts. He was gassed in the front line just before the battle, writes one historian; he found the decisive weak spot in the German line in a personal reconnaissance, wrote another. It's not an exaggeration to say that Côte de Châtillon gifted MacArthur with the reputation as the greatest combat commander of the AEF. One recent historian claimed the MacArthur greatly exaggerated his roll in the operation, but he has not found much support from others who have studied the battle.

The 151st Machine Gun Battalion Played a Key Role in the Final Assault

In any case, MacArthur’s determined 84th Brigade of “Alabama cotton pickers and Iowa corn growers” with both ingenuity and raw courage ultimately forced their way past the Germans. Those men who first reached the summit had a thrilling view. Looking north there were no more hills to assault, the rolling countryside had returned, and the entire road to Sedan could be seen. Victory was in sight and closer than anyone would have believed that day. What most needs to be most remembered about the action, however, was its costliness. The Rainbow Division suffered 3,000 casualties in five days of fighting in this sector. Well over half of these were on the slopes of Côte de Châtillon, which was, indeed a microcosm of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

Sources: Roads to the Great War. Read our review of an outstanding new work on Côte de Châtillon, The Best World War I Story I Know, HERE

The AEF Advancing in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive

Rare photo of U.S. Infantry (Possibly 77th Division) Attacking North of St. Juvin During the Meuse-Argonne Offensive

|

100 Years Ago:

The Centralia, WA, Armistice Day Tragedy

The Four Veterans Killed at Centralia

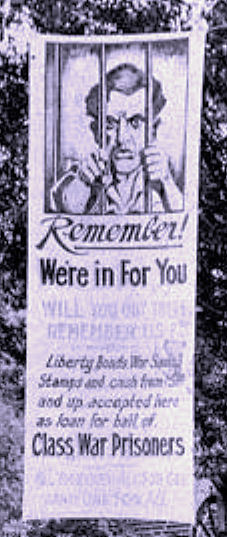

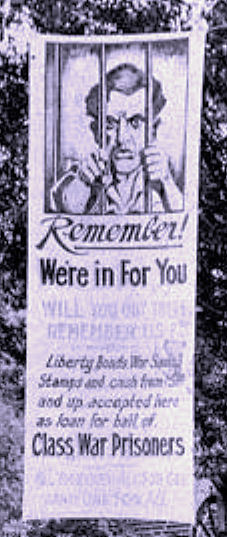

The Industrial Workers of the World, a radical labor union also known as the Wobblies, clashed with the established townsfolk of Centralia, WA (68 miles SE of Seattle), during an Armistice parade on 11 November 1919, the first anniversary of the end of World War I. Five people died violently that day — four gunned-down veterans and one IWW member, beaten, shot, and hanged from a narrow bridge over the Chehalis River.

IWW Poster of the 1919 Period

|

Tensions over labor conditions had been ongoing between the Wobblies and logging industry captains. The second of three Centralia IWW halls had been burned in a Red Cross parade a year earlier, and Wobblies were reportedly preparing for a raid on their third hall, now a vacant lot at the corner of Tower Avenue and Second Street. As the Centralia residents marched, IWW members waited with guns in their labor hall, at a nearby hotel, and on Seminary Hill. The workers, many of whom had come from outside the city for work, had drawn strong disfavor from groups like the Centralia Elks Club, the American Legion, and other business-oriented groups. Wobblies were known to use sabotage in Centralia and elsewhere in their push for a socialist economy in America.

The basic context that led up to the massacre makes the street battle a little less surprising. The events are described in the book Wobbly War, written by Longview newsman John McClelland, Jr. According to the author, the parade began at 2 p.m. It proceeded slightly past the IWW hall, where it turned around to march the other way. What happened next is hopelessly in dispute, except that it ended in the quick death of three of the Legionnaires–Warren Grimm, Arthur McElfresh, and Ben Cassagranda.

One marching veteran and some Wobblies said members of the parade suddenly dashed toward the hall and were in the process of breaking down the door when the Wobblies started shooting. Most of the Legionnaires, however, said the Wobblies began shooting from both sides of the street as part of a well-planned ambush on the unsuspecting veterans. Wesley Everest, a Wobbly who had served in the Army’s spruce logging division, ran from the Wobbly hall and was chased. In a final confrontation on the banks of the Skookumchuck River, Everest fatally shot Dale Hubbard, a young veteran who was trying to apprehend him.

Guard Detail on the Centralia Jail – After the Lynching

Everest was captured, beaten, and dragged through town with a belt around his neck to the jail, the site of Centralia’s current police station and City Hall. As the afternoon turned to evening, the mood of Centralia was apparently fearful and dangerous. That night, the lights went out downtown and Wesley Everest was removed from his cell, put in a car, and taken to the bridge at Mellen Street. He was hanged twice and shot several times. Some stories say he was castrated, though that remains under major dispute. His body was left to dangle through the night from the span over the Chehalis River near Mellen Street that came to be known as Hangman’s Bridge. No one was ever arrested or tried for Everest’s lynching. However, the episode had a long legal aftermath.

An excellent and full discussion of the tragedy was prepared by the National Park Service for the National Register of Historic Places and can be accessed HERE.

Source: The Daily Chronicle of Lewis County, 10 November 2017

|

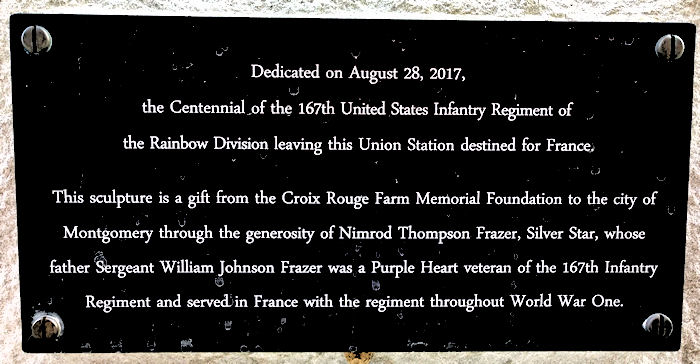

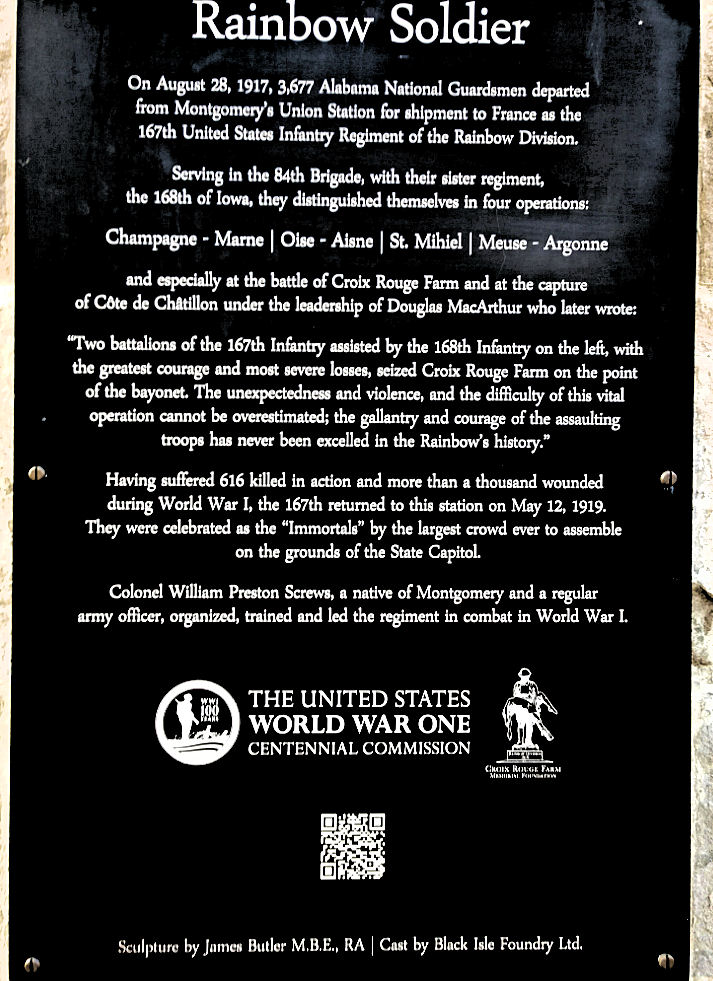

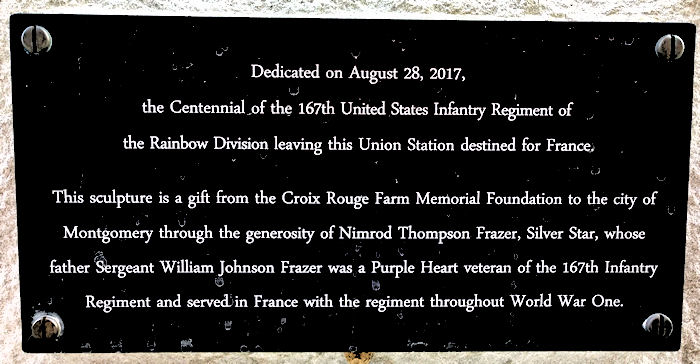

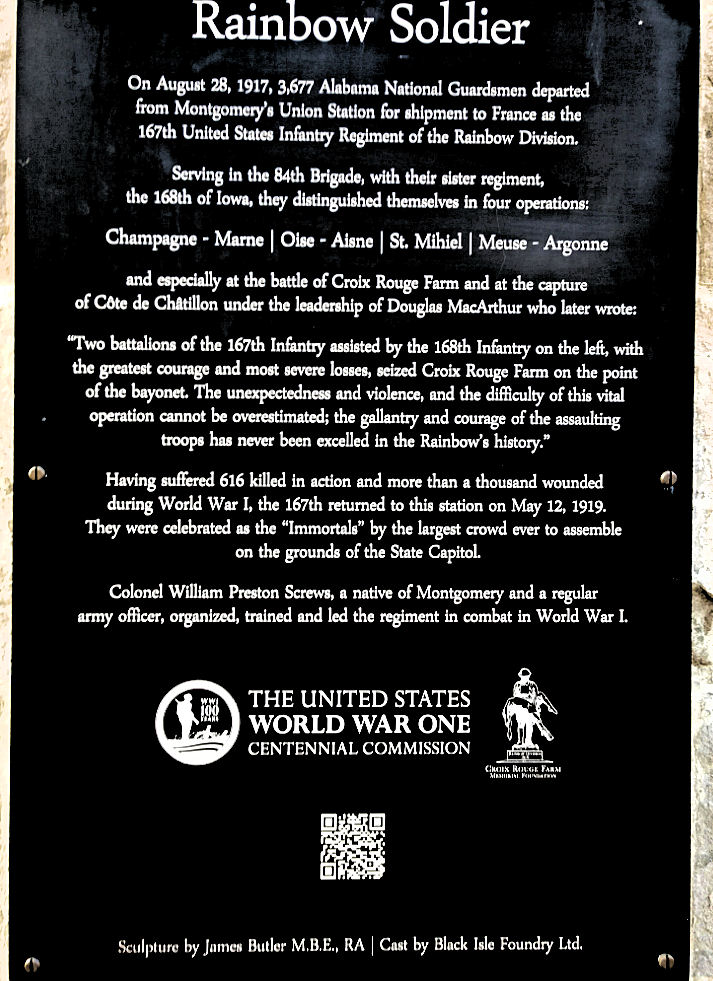

The Rainbow Soldier of Montgomery, Alabama

Sculptor: James Butler, British Royal Academy

One unit that fought in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive was the 167th Infantry of the storied 42nd Rainbow Division. The regiment was composed of men from the Alabama National Guard. Before the Meuse-Argonne operation, the Rainbow Division, with these Alabamians in the forefront with its sister regiment of Iowans, had fought a very difficult engagement at Croix Rouge Farm during the Second Battle of the Marne. Decades later, an Alabama businessman named Nimrod Frazer, whose father had fought at the farm, took it upon himself to see the men of the 167th were honored for their service. Ably supported by World War One Centennial Commissioner Monique Seefried, Frazer produced a history of the unit, Send in the Alabamians, and sponsored the creation of a monument, a bronze sculpture, to the men who fought at Croix Rouge. The monument was created by British sculptor James Butler and dedicated in France in 2011.

The sculpture at Croix Rouge proved to be a remarkable success and is now a pilgrimage site for American visitors to the Western Front. Funding was received to make a second casting possible. The new piece was dedicated at the Union Station in Montgomery, Alabama–the departure point for the 167th when they left for their federal service–in 2017. One of the features of the monument I particularly like is its highly detailed information panels, which are presented below.

A Big Thanks to Bob Knight for the Photos.

|

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications

|

Order Our

WWI Musical CD

Click on Image for Information

|

Shop at

Amazon.com

|

Order the Complete Collection

Over the Top Magazine

Click on Image for Information

|

A World War One Film Classic

Grim and inspiring story of the unit that found itself surrounded in the Argonne Forest in October 1918. Their survival and ultimate relief five days later is the basis of one of the greatest legends to come out of America's First World War combat.

The Lost Battalion scores high for the authenticity of the terrain, weaponry, combat scenes, and dialog. Although not a good match either in appearance or stylistically, Rick Schroder does well as on-site commander, Major Charles Whittlesey. The film focuses on the troops trapped in the pocket, so there's not a lot about surrounding events, like the relief mission in which Alvin York's division was involved, or the effort led by Whittlesy's old friend from Plattsburgh, baseballer Eddie Grant. The only significant flaw for me, however. was a demonizing of the 77th Divisional Commander, General Robert Alexander. I have never read, or heard, of any negligence on his part in extracting the trapped unit. The pace gets frantic, but then so did the battle. The DVD is available at both Amazon and Netflix. Don't miss it!

|

|

Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

(Or send it to a friend)

(Or send it to a friend)

|

Design by Shannon Niel

Content © Michael E. Hanlon

|