November |

Access |

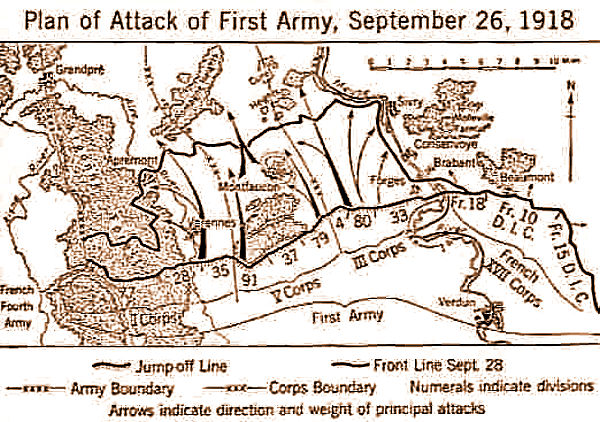

A First Day Success in the Meuse-Argonne Maj. Gen. Adelbert Cronkhite & Col. William H. Waldron, 80th Division Commander and Chief of Staff

With this issue, we are commemorating the 19th Anniversary of the St. Mihiel Trip-Wire. From myself, the editorial team, and our many contributors, THANK YOU for sticking with us over the years. We will keep producing issues for you as long as you keep reading. This month, we are drawing on the work of military historian and combat veteran Major Gary Schreckengost, U.S. Army, Retired, to look at a single day for a single division in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Gary has made a deep study of the actions of the 80th (Blue Ridge) Division during the great battle. From his writings, I've extracted the story of how the very ably led division managed to advance farther than any other American formation on the opening day of the battle. We have tried to provide sufficient maps and then and now photos of the battlefield to allow you to follow his narrative. Also, you might find the partial order of battle for the division in the right-hand column helpful in keeping track of the division's units. MH

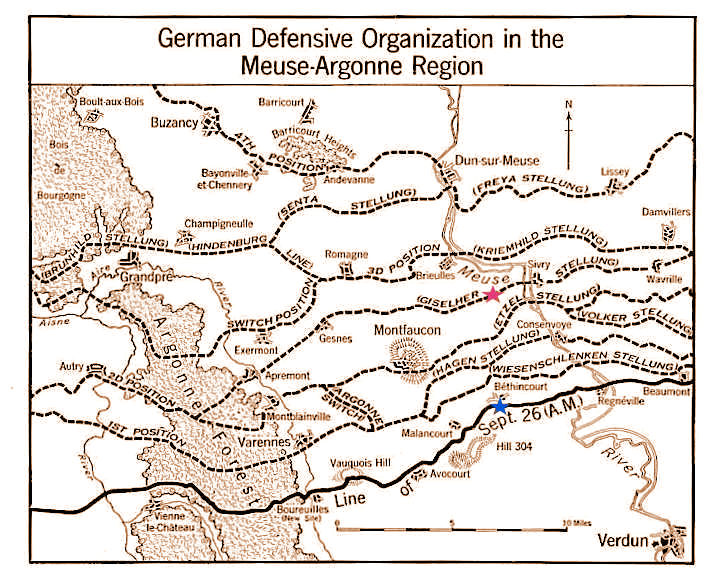

Note the 80th Division's Position as Part of III CorpsThe Achievements of the Blue Ridge Division

The Blue Ridge Division was the only combat division in the AEF to be given a major role in all three phases of the Meuse-Argonne.

|

Different Perspectives First Haircut in France

Various looks at the experience of the 80th Blue Ridge Division in the Great War

Under Fire,

|

|||||

Free Publications |

||

|

Amazon.com |

||

The Organization of the 80th Division

Shoulder Patch,

80th Blue Ridge Division

These are the main units of the 80th division involved in the action of 26 September 1918. A full list, including supporting units can be found HERE.

159th Infantry Brigade

317th Infantry Regiment

318th Infantry Regiment

313th Machine Gun Battalion

160th Infantry Brigade

319th Infantry Regiment

320th Infantry Regiment

315th Machine Gun Battalion

155th Field Artillery Brigade

313th Field Artillery Regiment (75 mm)

314th Field Artillery Regiment (75 mm)

315th Field Artillery Regiment (155 mm)

305th Trench Mortar Battery

314th Machine Gun Battalion

305th Engineer Regiment

305th Field Signal Battalion

Source: AEF Order of Battle

At Bois de Borrus the Night Before the Meuse-Argonne

Before Action

AFTER THE MEN had had their coffee—I remember I drank a good swig of it, too—I gave directions that the men should get in shape to move out of the woods. Then followed one of the most horrible experiences of my whole life in the war and one which I hope never to have to go through again.

Major Ashby Williams, 80th Division

The Boche began to shell the woods. When the first one came over I was sitting under the canvas that had been still spread over the cart shafts. It fell on the up side of the woods. As I came out another one fell closer. I was glad it was dark because I was afraid my knees were shaking. I was afraid of my voice, too, and I remember I spoke in a loud voice so it would not tremble, and gave orders that Commanders should take their units to the dugouts which were less than a hundred yards away until the shelling was over, as I did not think it necessary to sacrifice any lives under the circumstances. Notwithstanding my precautions, some of the shells fell among the cooks and others who remained about the kitchens, killing some of them and wounding others.

In about twenty minutes I ordered the companies to fall in on the road by our area preparatory to marching out of the woods. They got into a column of squads in perfect order, and we had proceeded perhaps a hundred yards along the road in the woods when we came on to one of the companies of the Second Battalion which we were to follow that night. We were held there perhaps forty-five minutes while the Second Battalion ahead of us got in shape to move out.

One cannot imagine the horrible suspense and experience of that wait. The Boche began to shell the woods again. There was no turning back now, no passing around the companies ahead of us, we could only wait and trust to the Grace of God.

We could hear the explosion as the shell left the muzzle of the Boche gun, then the noise of the shell as it came toward us, faint at first, then louder and louder until the shell struck and shook the earth with its explosion. One can only feel, one cannot describe the horror that fills the heart and mind during this short interval of time. You know he is aiming the gun at you and wants to kill you. In your mind you see him swab out the hot barrel, you see him thrust in the deadly shell and place the bundle of explosives in the breach; you see the gunner throw all his weight against the trigger; you hear the explosion like the single bark of a great dog in the distance, and you hear the deadly missile singing as it comes towards you, faintly at first, then distinctly, then louder and louder until it seems so loud that everything else has died, and then the earth shakes and the eardrums ring, and dirt and iron reverberate through the woods and fall about you.

This is what you hear, but no man can tell what surges through the heart and mind as you lie with your face upon the ground listening to the growing sound of the hellish thing as it comes towards you. You do not think, sorrow only fills the heart, and you only hope and pray. And when the doubly-damned thing hits the ground, you take a breath and feel relieved, and think how good God has been to you again. And God was good to us that night—to those of us who escaped unhurt. And for the ones who were killed, poor fellows, some blown to fragments that could not be recognized, and the men who were hurt, we said a prayer in our hearts.

Such was my experience and the experience of my men that night in the Bois de Borrus, but their conduct was fine. I think, indeed, their conduct was the more splendid because they knew they were not free to shift for themselves and find shelter, but must obey orders, and obey they did in the spirit of fine soldiers to the last man. After that experience, I knew that men like these would never turn back, and they never did.

Experiences of the Great War (1919)

The Morning Advance

By Gary Schreckengost

Béthincourt Village Secured

The Division's 160th Infantry Brigade attacked at 0530. Once O'Bear's 319th Infantry on the right and Holt's 320th Infantry on the left conducted a passage of lines with the engineers and were through the wire, they continued their advance in the fog and smoke about 1,000 feet to the barrage line along the road paralleling the creek. At exactly 0554, the barrage rolled forward at a pace of one hundred meters every four minutes, and "the 80th Division infantry advanced beyond the Forges Creek as close to the barrage as possible…following the curtain of shells which kept the Boche down in his dugouts [shielding them] from German machine gunners and artillery observers. The counter-artillery fire of the enemy was not heavy and at this point, his rifle and machine gun fire were not especially effective. The attack swept on, up the rising ground beyond, to the enemy's first position around Béthincourt village, which was taken without difficulty. According to Oberstleutnant (Lt. Col.) Hermann von Giehrl, the Chief of Staff of the XVI Corps, "The attack of the American infantry was greatly favored by a thick mist, which remained until late in the morning."

Capt. Josiah C. Peck, the Regimental Intelligence Officer of the 319th Infantry remembered the advance:

As the Blue Ridgers advanced farther up their axis of advance, they quickly came into contact with desultory 7.92mm German machine gun. and 7mm rifle fire from elements of German Reserve Division 7 who were posted in Tranchée CERVAUX-a series of inter-connected machine gun nests- which ran through the rubble field that used to be Village Béthincourt. . . As the leading assault battalions fought through and cleared Tranchée CERVAUX and headed north toward Tranchée BESACE and Hill 281 of Hagen Stellung, they were followed by machine gun sections that were supposed to help clear the way if/when they were held up.

We went forward with the road as our guide and I sent out runners to maintain contact with the troops ahead. Our course was due magnetic north. We reached the rear system of shelters in the ridge east of Cuisy, from which German prisoners had been taken. It was a smoldering ruin battered to pieces by our artillery. We passed up the ravine to the right of this system and halted in the hollow to await information of the troops ahead. While we were here, I remember, the fog and mist seemed to vanish as if by magic and the sun came out. I remember, also, that a Boche plane came over, flying low and firing at my troops with his automatic rifles. My rifles and machine guns drove him off.

From this ridge, also, I could see the troops ahead of us on the ridge along the Gercourt-Septsarges Road, working around the left flank of the Bois de Sachet. We could also see the smoke of the thermite shells bursting in the woods in the sector on our right. We passed down into the valley in front of us and halted and I went forward to see the situation, and watched from the crest of the ridge the movement of the troops on the left of the woods.

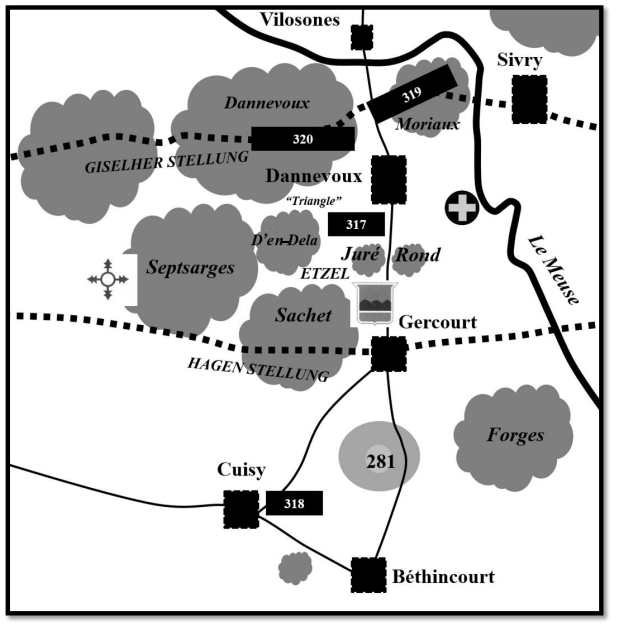

Author's Map, Zone of Operations for 80th Division

Among the mistakes made by some of the men of Brett's 160th Infantry Brigade (as well as the rest of the Army at this point) was that they either "walked ahead for the most part nonchalantly as though they were on route march" or they charged frontally against an enemy position before they had actually achieved fire superiority.

Meanwhile, there was the "mopping-up" to do, although the assault companies had pretty well finished the job themselves. We were supposed to work from left to right in our sector, but this beautiful theory didn't work in practice, for the rest of the detachment was now entirely out of my control, and I had to trust them to take care of the ground in front of them while my squad confined themselves to what was in our sight. To have attempted to go much to the flank with such a small group would have left us hopelessly behind and spoiled any chance of our making the way clear for our battalion. So we ran along the top of the trenches, heaving bombs into all dugouts that might contain hidden gunners or snipers, looking at scattered wounded Germans to assure ourselves that they were safely out of action, ready to kill them if they should show any signs of treachery, and making the prisoners who were not badly hurt run faster to the rear.

The old-fashioned way of "mopping-up" was to kill everything, and there is no possible doubt but that it was necessary for the days of closer personal combat and greater danger of treachery, but in the new open style of fighting, and with the Boche's general willingness to get safely to the rear as fast as he could, it was unnecessary and almost impracticable. Furthermore, we had been ordered to take prisoners whenever possible, because the Boche will stop shooting sooner to go to the rear than when he knows he is in for sure death.

Approach to Gercourt Village on the HAGEN Defensive Position

Back at Béthincourt, meanwhile, two companies of the 305th Engineers and "500 pioneer infantry under Captain Kenney" were working "with excellent skill and speed against great odds to get that bridge [critical for bringing supplies and artillery] up." Once the component parts arrived to the bridge site, the Blue Ridge engineers had their "Single Lock Bridge" up by 0900. As the last plank was laid in position, the 313th Artillery's first gun rolled across.

Afternoon and Evening

By Gary Schreckengost

Division Machine Gunners Advancing in the Afternoon

The German Defenses

By noon on 26 September, the Doughboys had overcome resistance by enemy machine gun nests in Bois de Forges and Bois Juré and were approaching corps objective. According to Capt. Frank Crandall of the 313th Artillery:

As per German Army tactical doctrine, HAGEN, being the initial Widerstandslinie (line of defense) of the German network in the Meuse-Argonne, wasn't all that heavily defended. In the Blue Ridge Division's zone, for example, perhaps 500 soldiers from German Reserve Division 7 manned its works. (See Zone Map above.) The men of German Reserve Division 7 were ordered to simply dispute the Blue Ridgers' advance and then fall back to join their brethren holding ETZEL in Bois Sachet, Juré, and Rond, and after that, fall back to GISELHER, where they were to hold out as long as possible.

One must understand that unlike the American Army, which was organized around the rifle and believed that the machine gun was simply "a weapon of emergency" or "opportunity", the German Army was organized around the machine gun. By 1918, pretty much every reduced infantry platoon in the Kaisers' armies (meaning the Kaiser of Germany and the Kaiser of Austria-Hungary) was converted into three machine gun squads in which every man fired, fed, or protected a machine gun. The Kaisers may have lacked men by 1918, but not machine guns. These machine gun squads were backed by a company or battalion equipped with light 81mm, medium 170mm (6.9-inch), or heavy 250mm (9.8-inch) Minenwerfer (mine thrower-mortars), as well as pre-plotted artillery. General von Ludendorff recognized that more machine guns, Granatenwerfer (grenade thrower-rifles) and Minenwerfer were needed to offset the ever-increasing numbers of Allied soldiers arrayed against the Central Powers.

Rolling On Through Afternoon and Evening

Beyond Hill 281 the terrain sloped away in open meadows to the Bois de Sachet. In this woods, in the Bois Jure on the right and the Bois d'en-Dela, and the Bois de Septsarges on the left, the enemy had an organized machine gun defense which slowed up the advance considerably. This line of resistance was admirably placed. It was beyond the barrage zone of our light artillery and cleverly located to take advantage of ground forms and cover. The attack against the position was carried on from the middle of the morning through the afternoon. It involved the employment of skirmish line tactics and advances by small elements under covering fire. The enemy was driven back into and in some cases through these woods during the early afternoon. Once the HAGEN trenches were breached, what was left of Village Gercourt was cleared of Germans by the 319th Infantry through the use of “effective rifle grenade fire.” As the men poured into the blown-up town, it was clear to them that the Germans had used it as a headquarter with a field hospital and an engineering supply dump for the HAGEN trenches located there.

As the two regiments of the 160th Infantry Brigade paused just north of HAGEN to wait for the artillery to shift fire onto position ETZEL ("wait thirty-five minutes while the barrage was again laid down ahead of us"). A battery of the 313th Artillery, led by its mounted artillery liaison officers, scouts, and markers, was advancing north toward Hill 281 where it was forced to stop to fill in a captured trench with pre-fabricated fascines before it could roll its guns forward.

By mid-afternoon, though, the newly arrived supporting artillery fire allowed the breaching of both HAGEN and ETZEL by the 80th Division in their sector (the only division to do so on the first day, by the way). The two adjoining American divisions helped secure the Blue Ridge's capture of ETZEL. On the east side, the 319th Infantry was to punch through just west of Gercourt and then breach the ETZEL trenches in Bois Juré-Rond, adjoining with units from the 131st Infantry of the 33rd Division. To the west, the 320th Infantry was to attack just south of Bois Sachet, breach ETZEL in Bois Sachet, and adjoin with the 47th Infantry of the 4th Division in Bois d'en-Dela and Septsarges before it took on GISELHER north of the Dannevoux Heights.

Dannevoux Village Captured in the Evening

GISELHER Behind the Heights in the Distance

Despite strong opposition developing about 1700, new attacks were mounted through the evening. The 319th Infantry, the first American unit to breach HAGEN, was to take Village Dannevoux, which lies in a gentle valley along the Meuse. The 320th Infantry was to cross the Septsarges-Dannevoux Road and complete the mission of capturing Bois Septsarges in conjunction with units from the 4th Division, operating on their left. Both regiments were supported by elements of the 317th Infantry of the 80th Division. At 2000 hrs. battalions of the 319th Infantry moved up through the trees south of Dannevoux, formed in front of its machine gun positions, and then made lots of noise. The Germans soon got wind of what was happening and up went the SOS signal to their artillery. In short order, a German barrage came down into the woods, but the attacking infantry had left the woods, and, in advancing across the open, captured Dannevoux.

By midnight, the officers and men of the 160th Infantry Brig., as well as those from the light artillery regiments were pretty spent and "the situation was not stabilized." They had been up for over two days straight, had broken through the HAGEN and ETZEL trenches and had advanced some seven to eight km from Béthincourt to Dannevoux and had kicked in the door of GISELHER along Dannevoux Heights in Bois Moriaux. After posting sentries and gas guards (men who were to use their sniffers to give warning of a gas attack), the men in the rifle companies tried to get some shut-eye in the light drizzle and waited for further orders, which were certainly going to be "continue the attack north." In making the longest advance of any of Pershing's divisions on that first day of the Meuse-Argonne Offense, the Blue Ridge Division suffered 210 casualties, which is relatively light considering what other American divisions had suffered in the opening advance.

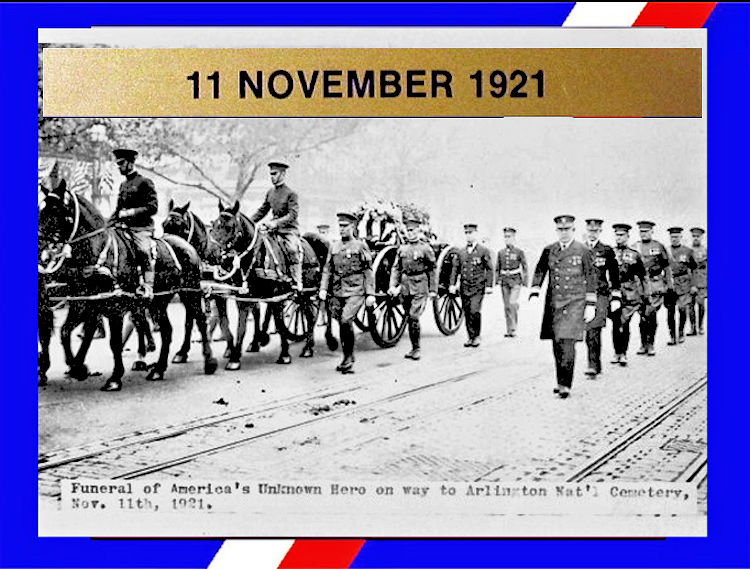

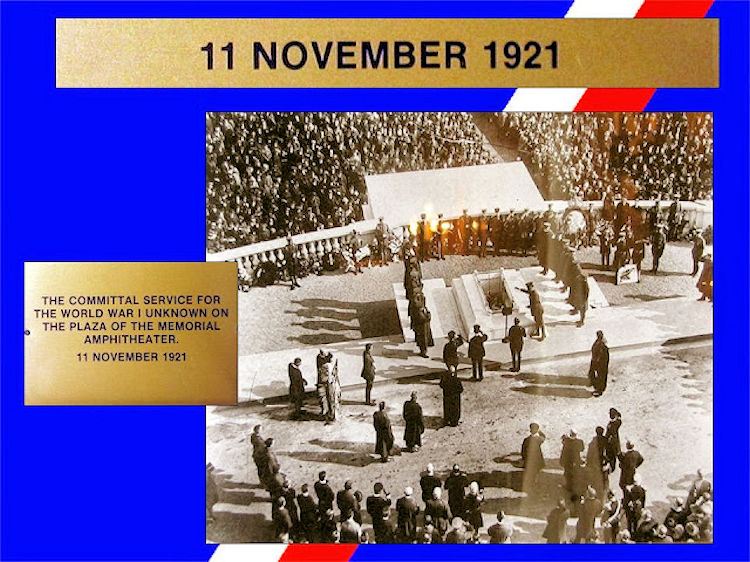

100 Years Ago:

|

The Return from the Argonne

New World War I Memorial for

Montgomery, Alabama

Sculptor James Butler, RA, with His New Work

On 11 November 2021, 103 years after the Armistice that ended WWI and 100 years after the return of the American Unknown Soldier to Arlington Cemetery, a bronze sculpture entitled The Return from the Argonne, from British sculptor James Butler, RA, will be inaugurated in front of Montgomery Union Station. This gift is made to the city of Montgomery by the Croix Rouge Farm Memorial Foundation through the generosity of longtime community, business leader, and Korean War veteran Nimrod T. Frazer, Silver Star.

The Return from the Argonne will complement the Rainbow Soldier, another bronze sculpture from James Butler located at Union Station, which remembers specifically the legacy of the 167th Infantry of the Rainbow Division. It was from this very same Victorian Railroad station that these National Guardsmen departed for France in August 1917 and where they returned in May 1919. The memorial also will honor all the Alabamians who fought in the Meuse-Argonne campaign, and the African American soldiers, mostly from Alabama, from the 366th Infantry of the 92nd division. The Return from the Argonne will remember them as well as another Alabama native son, the famous bandleader James Reese Europe from Mobile, who served in the Argonne. He led the military band of the 369th regiment (Harlem Hellfighters) which brought jazz to Europe.

Officers of the 167th Alabama Infantry, 1917

The Public is invited to attend this historic event. Among those who will be attending the 11 a.m. statue dedication at Montgomery's Union Station on 11 November 2021, will be representatives from France, as well as military leaders, elected officials, and business and community leaders.

Thanks to Monique Seefried for contributing this material.

A World War One Documentary

This video is an unchronological compilation of Army Signal Corps films of the 80th Blue Ridge Division around the time of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Nevertheless, it is well worth a look. The actual battle scenes—less than a quarter of the film—are gripping. These include the troops moving through captured territory past disabled artillery and dead enemy soldiers (see image above), the destruction around the village of Béthincourt—an early objective for the division—and a machine gun unit cautiously advancing through a forest to set up their guns. A herd of mules interrupting the Doughboys' advance makes an amusing appearance.

The non-combat sequences are also surprisingly interesting. Live-fire training on machine guns, rifle grenades, and mortars is shown. The best episode involves a visit by General Pershing to Division Headquarters. He is clearly pleased with the performance of the Blue Ridge boys, not at all in his reportedly frequent kick-ass-and-take-numbers frame of mind. Overall, this is a film for real AEF connoisseurs; it has a gritty and authentic "You Are There" feel to it.

Sources: YouTube

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon