December

2020 |

|

|

|

War in Wintertime

General Winter Oversees His Battlefields

An Italian Sentry in the Alps

|

Having never been in combat myself (I spent all my six years in the Air Force stateside), I have depended on conversations with those who have "seen the elephant" and reading first-hand accounts for my understanding of the experience. My overriding impression after digesting all these sources over the decades is that the REAL DEAL of combat is uniquely demanding. Besides the immediately dangerous stuff like getting shot at or having an IED detonate under your vehicle, etc., etc., I have been led to believe that even when it's not especially intense, warfare also involves lots of physically exhausting labor such as digging, long marches,

more digging, and slinging heavy items like artillery shells around, to the point that many just drop from exhaustion—physical and/or mental. Soldiers suffer. That's sort of the baseline. Could it get even worse? Yes! For this issue of the Trip-Wire, we are going to examine a type of combat experience in which all the things soldiers must do are magnified in difficulty due to cold, rain, mud, snow, ice, and lousy visibility. Each of which (and they do come in combinations, too) multiply that suffering factor. Welcome to winter warfare in the Great War.

MH

Carpathian Winter Fiasco

By Graydon A. Tunstall

K.u.K. Machine Gunners

In mountain operations protection from the elements is often as important as protection from enemy fire.

NATO Manual

The Carpathian winter war of 1915 presents one of the most significant — and, in

terms of human sacrifice,

most tragic — chapters of World War I. The mountain

battles that pitted allied Austro-Hungarian and German

armies against Russian troops were unprecedented in

the age of total war. In the winter of 1915, the Dual

Monarchy launched three separate and equally ill-conceived offensives: an initial effort on 23 January; a second uncoordinated assault on the Russians on 27

February; and a third and final effort to liberate

Fortress Przemysl in late March. The Karpathenkrieg comprised three separate campaigns launched by the Habsburg Supreme Command

from mid-January to April 1915. The Eastern Front

operation, which ultimately engaged more than one million men on each side, could hardly have been

conducted under worse conditions. The Carpathian

Theater lacked the railways, roads, communication

lines, and other important resources necessary for

maneuvering mass armies. Moreover, the contenders

soon found themselves ensnared in an inhospitable

mountain environment in wintertime.

The Habsburg command had made no prewar

contingency plans for a mountain campaign lasting into

the winter months — one of its many failures — and

this would prove to be a disastrous mistake. Infantry

masses were deployed into the mountainous theater

with no provision for winter uniforms or suitable

equipment. Conrad's troops were sent to the mountains in winter without the most rudimentary winter

provisions, including warm clothes, and saws with

which to fell trees for firewood. Boots with cardboard

soles, for example, quickly became unusable.

Thousands of Habsburg troops fell victim to "the white

death,” living in the open in subfreezing temperatures

with no shelter. Weary soldiers spent the long winter

nights struggling to stay awake to avoid frostbite or

freezing to death as nighttime temperatures dropped

to as low as -25°F. Emotional fatigue set in amongst

the living, compounded by the lack of food and sleep.

Nevertheless, Conrad's soldiers continued their attacks. Troops were expected to undertake exhausting

marches through meter-deep snow to reach the

battlefield, only to find no shelter awaiting them. In a

cruel twist of fate, frigid conditions were interspersed

with sudden periods of rising temperatures and thaw.

Steady rain and melting snow turned the valley terrain

into a pit of mud as troops, artillery, ammunition,

animals, and supply wagons sank into the mire. Rising

floodwaters swept away bridges and soldiers were

forced to lie in the waterlogged positions.

The troops had to dig out in order to go on patrol,

launch an assault, or clear defensive positions and the

limited roads and trails essential for the movement of

supplies. The shoveling required hours, sometimes

days, and the burden of these tasks contributed to the

physical and moral decline of Habsburg forces. Utterly

exhausted, many of the troops became apathetic or

committed suicide by shooting themselves or exposing

themselves to enemy fire. Tens of thousands of horses,

too — critical to the Habsburg supply chain — succumbed to overexertion and starvation.

Russian Artillery in the Carpathians

Habsburg Third Army suffered immense losses during

the first Carpathian offensive. Two weeks after it

began, official sources listed 88,900 men as casualties.

Their total losses during the offensive exceeded 75

percent, most of them resulting from severe frostbite,

exposure, or illness. The Third Army commander, Svetozar Boroevic, rightfully claimed that his army had

not been prepared for the demands of a mountain

winter campaign.

On 1 March, during the second offensive Colonel Georg Veith of the Third Army

wrote: "Fog and heavy snowfalls, we have lost all

sense of direction; entire regiments are getting lost,

resulting in catastrophic losses." Habsburg archduke

Joseph August, commander of VII Corps, reported that

over two days his Hungarian Honvéd Division "suffered

terrible losses; its effective force numbers less than

2,000. . .and tomorrow, despite the casualties, we

have to attack again. My corps losses since 1 March: 12

officers, 1,121 men killed, 46 officers and 2,121 men

wounded, 2 officers and 685 men missing. This is really

terrible."

With the failed third Carpathian push grinding to a halt, the army's offensive efforts ended on 23 March. When

Conrad ordered the South Army commander to

transfer "dispensable" units to the embattled Third

Army, he declined, stating that he required them for

future operations. Conrad grew despondent, with

his adjutant describing the situation as hopeless. An

entry in the V Corps logbook observed, "It is as though

Heaven is against us. When we attack, it starts snowing

and more than one meter deep. When the Russians

attack, the snow freezes and movement is possible."

Austrian Troops Retreating

For the Dual Monarchy, never to be forgotten was the series of operations that opened in 1915 in the Carpathian Mountains. Conrad's flawed planning and failures in the campaign also resulted in the German military exerting greater control over the Habsburg command structure. One of the

most ill-conceived campaigns of the war, the Carpathian winter war offers far too many examples of how

not to conduct winter mountain battle and provides a

stark lesson about the negative effects of inadequate

leadership.

Religious souls visualize hell as a blazing inferno with burning embers and

intense heat. The soldiers fighting in the Carpathian Mountains during that

first winter of the war know otherwise.

Colonel Georg Veith, Third Army, k.u.k.

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

|

|

Season's Greetings from the Editors

Different Perspectives

Here are some very informative sources about some of the battles that took place in the winter months of the Great War.

Winter Battle of the Masurian Lakes

Winter Battle of the Masurian Lakes

The Great War on the Vosges Front

The Great War on the Vosges Front

Fighting the Russians in Winter PDF (Includes study of U.S. Operations in Northern Russia)

Fighting the Russians in Winter PDF (Includes study of U.S. Operations in Northern Russia)

Winter operations 1914–1915

Winter operations 1914–1915

The Nightmare of Alpine Warfare: Avalanches!

The Nightmare of Alpine Warfare: Avalanches!

The "Turnip Winter"

The "Turnip Winter"

Frostbite and Trench Foot in the Trenches

Frostbite and Trench Foot in the Trenches

The Great Gallipoli Blizzard

The Great Gallipoli Blizzard

Meteorology in World War One

Meteorology in World War One

Colonel Cold strode up the Line

(tabs of rime and spurs of ice);

stiffened all that met his glare:

horses, men and lice.

Visited a forward post,

left them burning, ear to foot;

fingers stuck to biting steel,

toes to frozen boot.

Stalked on into No Man’s Land,

turned the wire to fleecy wool,

iron stakes to sugar sticks

snapping at a pull. . .

"Winter Warfare,"

Edgell Rickword

Support Worldwar1.com's

Free Publications

|

Shop at

Amazon.com

|

Winter Avalanches

During the three-year war in the Austro-Italian Alps at least 60,000 soldiers died in avalanches. [This conservative statistic comes from the research of Heinz von Lichem, in his outstanding three-volume study Gebirgskrieg 1915–1918.] Ten thousand died from avalanches in the "lesser" ranges of the eastern half of the high front—the Carnic and Julian Alps. In the "high" Alps to the west, the Ortler and Adamello groups, the Dolomites, avalanches claimed 50,000 lives.

To put these casualties in perspective, a total of 25,000 troops were killed by poison gas on this war's Western Front in Belgium and France. Gas killed an additional 7,000 men on the Austro-Italian front, the greater part on the plains and plateaus along the Isonzo and Piave rivers. [Gas is not very effective in the cold windy atmosphere of mountains.]

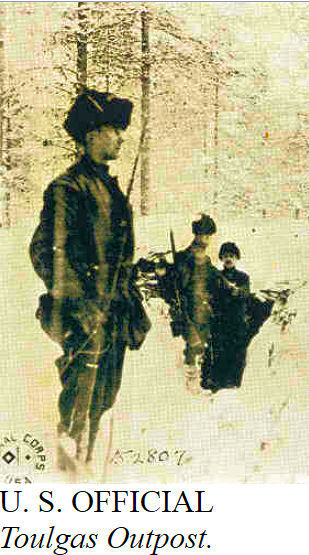

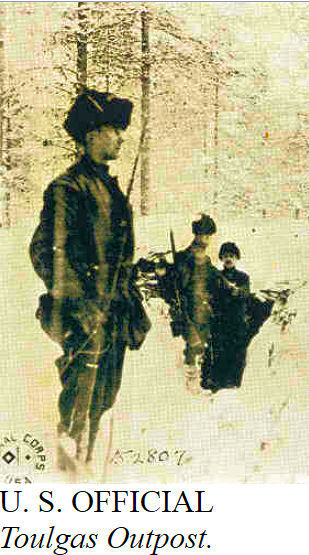

The Polar Bears' Biggest Challenge

An American "Polar Bear" 1918

In September 1918 a contingent of 5,000 American troops landed in Archangel, Northern Russia. Their evolving mission over the next 7 months was initially to prevent massive amounts of war supplies from falling into the hands of Germany. They ended up fighting Bolshevik forces, but the terrain and climate of Murmansk and Arkhangelsk were the most obvious obstacles for Allied operations. A sprawling

morass of forests, impassible in the summer and snow-covered

in the winter, blanketed the region. There were no roads so that mechanical transport could not be used, but countless tracks led in every direction and no existing maps showed where they ran. The port of Archangel would be cut off from Europe, except for occasional mails brought by sleigh

across the long road from the Murmansk Railway.

Allied soldiers unaccustomed to the

subarctic climate had to operate in perpetual twilight, which

limited visibility and damaged morale. The environment thus dictated that winter engagements revolved primarily around shelter. . . Red soldiers [who had assaulted an American bunker] died within minutes of being hit, becoming “frozen stiff in the intense cold.”

Whatever questions emerged

over American participation, the soldiers who served in Russia

did so with distinction, operating in difficult conditions against an

unclear enemy. In doing so, they suffered a reported 553 casualties,

including 194 deaths.

House and Curzon, The Russian Expeditions, 1917-1919

WWI Support Needed

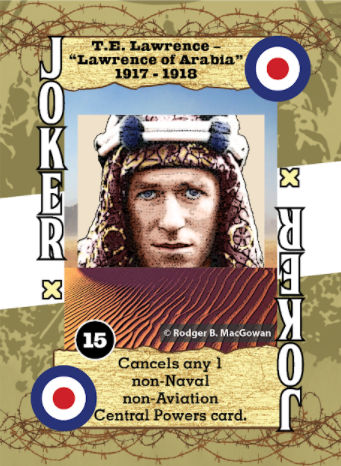

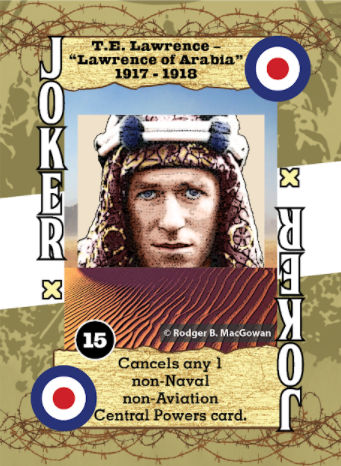

Click on Playing Card to Connect

Friends of Worldwar1.com, game designers Rodger MacGowan and Dana Lombardy, have come up with a World War One-themed educational card game designed for both adults and young people (grades 8-12). Their effort is 75 percent funded on Kickstarter and they are close to production. If you would like to learn more about the game, contribute to its final production, or purchase a set as a Christmas gift, just click on the sample playing card above.

|

|

Cold on the Somme: Winter 1916-17

From the Imperial War Museum

Christmas Meal on the Somme, 1916

After the close of the Battle of the Somme in November 1916, the men on the Western Front dug in for the coming winter. That year, it proved to be exceptionally cold. All those who lived through the winter of 1916-17 had memories of the bitterly freezing conditions.

The severe cold tested the troops’ morale, as Victor Fagence, a private in the Royal West Surrey Regiment, discovered.

The winter of 1916-17 was notoriously a very, very cold winter. And for my part, I think I almost in my own mind then tasted the depths of misery really, what with the cold and all that sort of thing, you see. We were forbidden to take our footwear off in the front line. Although, I myself disobeyed that on one occasion. I was so cold when I came off sentry go, and we had a bit of a dugout to shelter in, when I went in there – this was before leather jerkins were issued – there was an issue of sheepskin coats. And I took my gumboots off and wrapped my feet in the sheepskin coat to get a bit of extra, you know, to warm them up a bit.

The icy weather made life during the day miserable—but the drop in temperature at night was even worse. Near 40th Division’s forward headquarters, British artillery officer Murray Rymer-Jones found an unusual way to cope with it.

Now, for our own comfort, to be in a tent with snow on the ground and the appalling cold was nobody’s business. You couldn’t have heating in the tents, you see. So the only thing I could do then was, we had a double loo heavily sandbagged all round in the entrance, you see, it was like little rooms. And although there was no connection between the two, you could talk to the chap next door! So Hammond, from another battery who came and joined us for a bit then, he and I used to sit in the loo most of the night – because it was so heavily sandbagged it kept it reasonably warm – and talked!

For the men who faced the winter in kilts, exposure to the bitter weather was unbearable. NCO J Reid served with the Gordon Highlanders.

We went up with these casuals and joined the battalion; the 6th battalion again, joined the battalion at a place called… I can’t remember the name of the place now. The battalion was made up to strength, anyway. And a couple of days after, we was on the march. It was the month of January, dead cold. Oh, God it was cold. We were going up to Arras which was about 30 km – 30, 40 km – from this place. We marched and I always remember that. Our knees were even frozen up, you know, with the usual field bandages to wrap up our knees and all up our legs to keep the frost from biting into our legs, our bare legs.

German Sentry on the Somme, Winter 1916-17

It wasn’t just the cold that made winter on the Western Front so difficult to endure. Flooded trenches were also a feature of life there, something which Harold Moore of the Essex Regiment found out to his cost.

The communications trenches were half full of water and they had to have these duckboards on the side of the trench to walk up to the front line. You had to come up, file up in single line, single file. And as we was going up to the line there was a fellow in front of me, he was a machine-gunner and he’d got two buckets of these circular ammunition what he used for his Lewis gun. He stopped for a moment, you know, cos they were heavy! I said, ‘I want to get by cos I’ve got to get up to the front line.’ ‘Well,’ he said, ‘you must wait; I can’t go any further for the moment.’ Well then I tried to get round the side of him and, as I did so, he just gave a heave of this bucket and it knocked me in the shell holes full of water.

The waterlogged ground meant the men soon found themselves in extremely muddy conditions. Andrew Bain of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders described the dangers of such an environment.

Mud and cold. Oh, for weeks we were up to the thighs in mud. And if we were moving forward to the trenches, many of the shell holes were filled up with muddy clay. And if a man fell into that he couldn’t get out. And they were simply drowned in mud. There was nothing could be done about it.

Because of the abnormally cold conditions that swept the Western Front that winter, the ground froze solid. This turned out to be lucky for officer George Jameson, who was based near Aubers Ridge.

I had gone over to a position on the ridge where I could observe one day and, as I say, the ground was iron hard. I was walking back and a gun started to fire. I suddenly heard this swish and I could tell by the very sound of it I could tell it was coming fairly near to me. Suddenly, there was a burst away to my right and I thought, ‘Well thank goodness for that, plod on chaps.’ I kept going on and suddenly the gun fired again, another one; it had changed its angle a bit and I heard this thing. It sounded as though it was coming extremely close. I hadn’t time to do anything. Just suddenly quite by my side there was this [noise] and, about 150 yards beyond me, the shell burst. What had happened, the ground was so hard that the shell had just glisséed on the surface, you see. It struck within about a yard to the right-hand side of me as I was walking and then went on and in the air, about 150 yards beyond, it burst. Now, if that had been soft I’d have had that. That’s the kind of thing that happened. Not me this time chaps, on, on!

British Troops at Beaumont Hamel, Winter 1916-17

The weather also affected the vehicles used along the Western Front. Antonia Gamwell worked as an ambulance driver with the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry.

Of course in the winter it was bitter and we couldn’t keep the cars mobile, I mean they just froze of course if they were left to freeze. But we had to keep winding them up. We tried every other way, we tried putting hot bottles in the engines and under the bonnet and heavy bonnet covers and every device we could possibly imagine, but it was no use. We had to simply stay up, there were details. So many of us – six I think it was – used to be on duty and every twenty minutes we went up and wound up the whole lot.

Despite the extra layers, many of the men still fell victim to frostbite and trench foot. Walter Grover was a private in the Royal Sussex Regiment.

All the time you’ve got in the trenches you never knew you’d got trench feet. Your feet were terribly cold with no feeling but when you got out of the line and you took your boots and socks off then your feet swelled up and you could never get your boots on again. And the agony of trench feet, you know, chaps used to groan with it and of course some actually lost their feet with it, you know, frostbite. Trench feet is something to be endured to describe it.

In extreme cases, men even died from exposure to the biting cold. Charles Wilson came close to such a fate with an attack of pneumonia.

We were behind the line; we were in reserve, we were at Mametz Wood. We were under canvas in the middle of winter, this was December and I’d been down on a course and had come back. And my kit had gone on up, I knew where the battalion was, I was there before I left, I knew the way up to the battalion and had left my kit to be sent on, my valise, to be sent up with the rations. But my kit never arrived and I had no cover and the battalion had only one blanket per man. It was a very hard frost and I arrived at this place very hot and sweaty and got a chill and was carried down from that to hospital.

Front Line on a Glacier: The Marmolada

By Richard Galli

North Glacier on the Marmolada

The highest mountain in the Dolomite range of the Alps at 3342 meters, the Marmolada (marmalade) Massif or "group" comprises of a vast northern glacier and a soaring, semicircle of cliffs and peaks on the sunny southern side. Three months of summer and nine months of winter make its annual weather cycle. Astride the old, pre-1915 border of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Kingdom of Italy, this icy giant became a major battlefield of the First World War's Gebirgskreig or Italian Front. As with Tofane, Monte Piano, and the Tre Cime massifs in other mountainous sectors, Marmolada was vital to the control of its region.

Topside Ice Trench

Marmolada had all characteristics and dangers unique to high mountain warfare, including the thin atmosphere [70 percent of sea-level at 3,000 meters in altitude]; ice, snow, and scree; and frequent blizzards or dense fog banks covering attacks. Avalanches, falling rock and lightening, long-range shooting duels, artillery, and hand to hand fighting; as well as exposure to extremely low temperatures and high winds killed men in equal numbers. Injuries such as frostbite, snow blindness, altitude sickness, and malnutrition caused by the severe climate competed with the usual war wounds, disease, and stress—especially for troops that must stay on position and not let down their guard. Patrols, observation posts and assault units resembled mountaineers as much as soldiers. Supply was carried out by backbreaking corvée [on the backs of men and mules] and téléphérique [both manpowered and motor-driven cable-cars.] Despite being surrounded by frozen water, this vital need of humans was difficult to obtain or store. With most of their army in Russia, the Austrians concentrated on defending their empire's lofty southern flank. On Marmolada, between the Italian and Austrian forces, was a vast no-man's-land of glacier crevasse and bergschrund or soaring rock cliffs, needle-like arêtes, and knife-edge ridges with their blocking "gendarmes." All these are great challenges for mountaineers defining war on this Alpine front as somewhere between unique and incredible.

Glacier Combat

Patrolling — Artillery Port — Connecting Tunnel

Combat on this icy amphitheater began in 1915 with a rush for the high points unoccupied in times of peace. In June the first action took place with the Alpini Belluno Battalion capturing the strategic Padon and Ombretta Passes. The word "pass" is a stretch, for only to climbers were these notches on knife-edge ridges considered passes. They did, however, look down onto the great glacier and Austrian positions. While Austro-Hungarian forces controlled the massif's central ridge, the Punta Penia [3342 m.] summit and the cliffs below it, as well as the great northern glacier, the Italians controlled, or one might say "clung" to the southeast and southwestern cliffs. In winter the basic strategy became survival, a mighty undertaking for large groups of men in these high mountains, from the first deep snowstorms in September until the last blizzards of heavy snow in May.

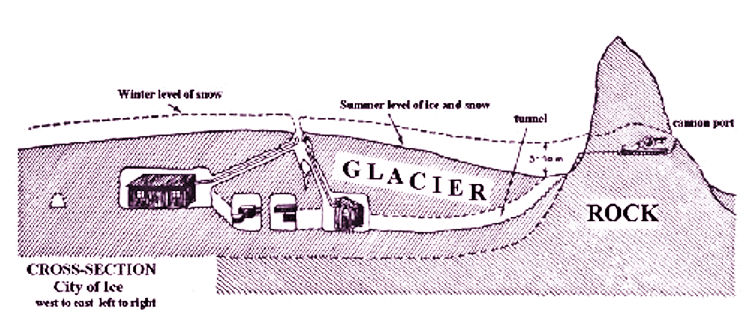

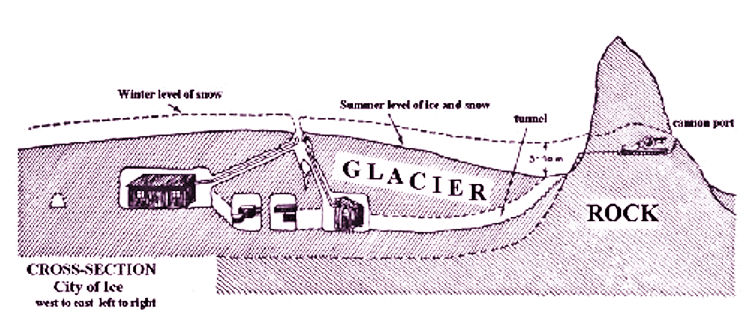

It was beneath the surface of the great glacier that a "city of ice," unseen and untouchable by Italian artillery or gunfire, was constructed. Designed by Lieutenant Leo Handl of the Kaiserjager, a labyrinth of tunnels connected five clusters of buildings or "cities." [see map] Each outpost was composed of barracks, electric generators, supply depots, first aid stations, and kitchens. Some of these buildings were beneath 60 meters of glacial ice. Cable cars brought soldiers and supplies to the last safe [from fire] ridge, where they went beneath the glacier through tunnels bored through rock connecting to ice passages. From rock ridge and cliff poked the snouts of machine gun and cannon, with their hidden ports and interlocking fields of fire.

Concept of the Ice City

The last full-scale battle on Marmolada was during the last week of September 1917 when Alpini units, a battalion of the 3rd Bersaglieri and a regiment of regular infantry [Alpi Brigade], captured Point 3259, also known as Marmolada d'Ombretta. The victory was short-lived, as in early November of 1917, the Italians abandoned their hard-won gains and positions on Marmolada without a shot, during the great retreat after Caporetto. Total losses by both sides in two years of fighting on and around the Marmolada amounted to over 9,000 dead—one third killed in action, another third dying in avalanches, and the remainder of cold-related injuries. Most of them remain entombed in the mountain's rock and ice.

|

100 Years Ago:

"Bloody Christmas" Brings D'Annunzio's Fiume

Extravaganza to a Close

D'Annunzio Raises His Flag Over Fiume, September 1919

Fiume, now know as Rijeka in Croatia, is a city on the east shore of the Adriatic. Through the Great War, it was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. The disintegration of the Empire at the end of the war, though, led to the establishment of rival Croatian and Italian administrations in the city; both Italy and the founders of the new Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) claimed sovereignty based on their "irredentist" ("unredeemed") ethnic populations. Volatile poet, warrior, and adventurer Gabriele d'Annunzio demanded the area around Fiume for Italy and began making passionate speeches for its seizure.

An international force of Italian, French, Serbian, British, and American troops occupied the city (November 1918) while its future was discussed at the Paris Peace Conference during the course of 1919. On 10 September 1919, the Treaty of Saint-Germain was signed declaring the Austro-Hungarian monarchy dissolved. Negotiations over the future of the city were interrupted two days later when a force of 2,000 Italian nationalist irregulars (known as arditi, after Italy's special assault troops), organized and led by Gabriele d'Annunzio, seized control of the city, forcing out the international security force. The local Italian population was thrilled by his arrival.

D'Annunzio then established a state, the Italian Regency of Carnaro. To the embarrassment of the Italian government, several ships mutinied and offered their service to d’Annunzio. For 16 months he ruled Fiume as a dictatorship founded on anarcho-syndicalist-decadent ideals (a city for poets and pirates), while Italy pondered what to do. When they continued to condemn his project, he even formed an Anti-League of Nations that reached out to "oppressed peoples" around the world.

D'Annunzio's Arditi Supporters, October 1919

According to one account, artists, bohemians, adventurers, anarchists (d’Annunzio corresponded with Malatesta), fugitives and Stateless refugees, homosexuals, military dandies (the uniform was black with pirate skull-&-crossbones, later stolen by the SS), and crank reformers of every stripe (including Buddhists, Theosophists, and Vedantists) began to show up at Fiume in droves. The party never stopped. Every morning d’Annunzio read poetry and manifestos from his balcony; every evening a concert, then fireworks. This made up the entire activity of the government.

The resumption of Italy's premiership by the liberal Giovanni Giolitti in June 1920 signaled a hardening of official attitudes to d'Annunzio's coup. On 12 November, Italy and Yugoslavia concluded the Treaty of Rapallo, under which the city was to be an independent state, the "Free State of Fiume," under a regime acceptable to both. D'Annunzio's response was characteristically flamboyant and of doubtful judgment: his declaration of war against Italy invited the bombardment by Italian royal forces which led to his surrender of the city at the end of the year, after a five-days resistance. This event was known as "Bloody Christmas."

D'Annunzio fled by airplane to Venice and escaped capture. His career as an independent political entrepreneur, however, was at an end. After the Fiume episode, d'Annunzio retired to his home on Lake Garda and spent his later years writing and campaigning. A few years later the king designated him a prince. Although d'Annunzio had a strong influence on the ideology of Benito Mussolini, he never became directly involved in fascist government politics in Italy. He died in 1938.

Sources: Wikipedia, History Today and Culture Trip

|

Remembering Those Oklahoma Doughboys

Carney Oklahoma's Doughboy

My friend and past battlefield traveling mate, Tim Daniel, who lives in Oklahoma, is an expert on the military affairs of his home state. One time, he educated me on the connections of Oklahoma through the 45th Division to none other than Adolph Hitler. Recently, Tim has taken it upon himself to survey the World War I memorials near home.

Here are two unique examples he has come across. Right-click on either of these images if you would like to see extra-large versions.

Above, Tim is at the Doughboy Memorial of Carney, Oklahoma. Located in Lincoln County, Carney is 20 miles northeast of Oklahoma City. Its population in 2010 was 647. The folk-art-style statue was created by sculptor Claude Fisher in 1936 and installed in 1940. Its inscription reads:

In Memory of Our Boys

1917-1918

In Honor of the Brave Troops of

WWI Who Were Known as the Doughboys

Lt. Walter Drew Memorial, Ardmore, OK

Ardmore, OK, is near the Texas border on Interstate 15. Here, Tim found this substantial family memorial in a local cemetery. The statue is a depiction of Lt. Walter Drew of the 141st Brigade of the 36th Texas-Oklahoma Division, who was killed in the Battle of Blanc Mont Ridge, 8 October 1918. He is buried next to his father Byron, who died in 1932. His commendation for his actions that day from French General Ferdinand Foch is included on the memorial plaque.

|

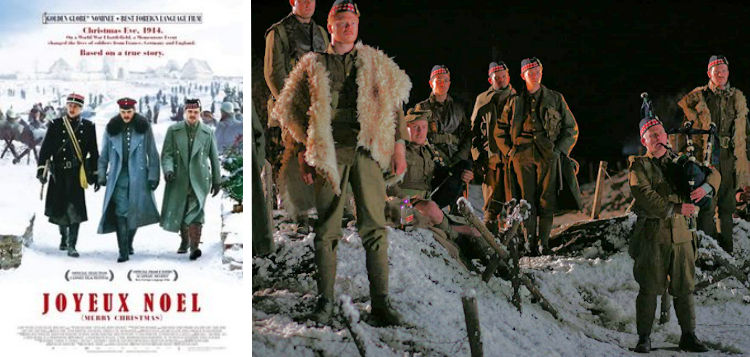

A World War One Film Classic

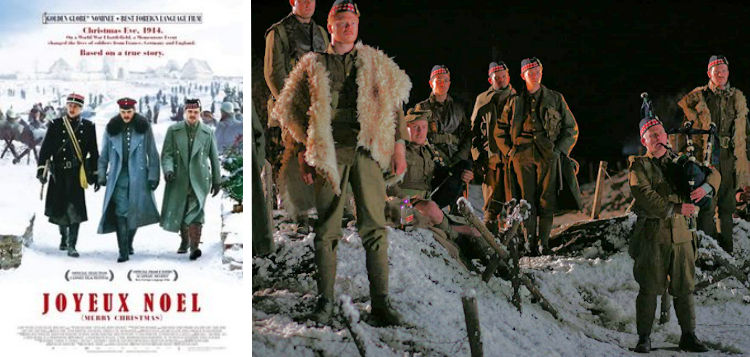

The famous Christmas Truce of 1914 is presented from three points of view in Joyeaux Noel—German, French, and Scottish—in this 2005 multinational production. Nominated for a Best Foreign Language film at that year's Academy Awards, it is (of course) extremely sentimental and strains credibility occasionally, but at the same time Joyeaux Noel has a feeling of authenticity for the emotions shown by the participants, some of whom are historical figures who really participated in the truce. For the most part, it also does a good job of capturing the scale of the war and the details of wintertime in the trenches. You'll recognize many of the international cast if you've spent any time during the Wuhan Flu lockdown binge-watching BBC and international productions on your TV. It's one of the last appearances of Ian Richardson, who played my favorite political schemer Francis Urquhart. (Where have you gone F.U. when we need you?)

For me, the most impressive thing about this film is the musical accompaniment. It's a mixture of Christmas carols, bagpipes, operatic solos, and alternating seasonal and military background music by composer Philippe Rombi that perfectly match the visuals and storyline.

Available as DVD from Netflix or purchase or rental streaming from Amazon. MH

|

|

Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

(Or send it to a friend)

(Or send it to a friend)

|

Design by Shannon Niel

Content © Michael E. Hanlon

|