The Grand Fleet's Sixth Battle Squadron and the Surrender of the High Seas Fleet

by Alan Weatherley

Alexandria, Virgina

Shortly after America declared war on Germany on April 6th., 1917 the Royal Navy paid off the last five King Edward VII class battleships still serving with the Grand Fleet. Launched between 1903 and 1905 these pre-dreadnoughts were hopelessly outclassed by the ships with which they were expected to do battle - should the Germans ever leave the security of their bases. Since the inconclusive clash at Jutland the previous year, the Kaiser's High Seas Fleet had shown little or no inclination to repeat such a sortie in strength and throughout this long period of inaction, officers and crews aboard the idle battleships and battlecruisers had grown estranged from one another with the result that morale was low. This disheartening situation had developed in spite of the fact that in ship on ship encounters the Germans had proved themselves to be equal to the British and thus might have been tempted to try and repeat their tactical success. (In the contest between battlecruisers which opened the conflict, three British ships, including the veteran of the Falkland Islands victory HMS Invincible, had been sent to the bottom with colossal loss of life in exchange for the destruction of just one of their own.) Notwithstanding their inactivity, the High Seas Fleet remained a potent threat and Britain was forced to maintain an active defense.

Although the Edward VII's were obsolete, they had made up the numbers which maintained the Royal Navy's physical and psychological superiority over their adversaries. The gap that their retirement created in the Grand Fleet's ranks was hardly catastrophic but it did give the Admiralty some concern. In order to fill this gap it was decided to invite their new allies to send a squadron across the Atlantic to join the British forces. After much consideration, the US Navy accepted this invitation and six

battleships were selected to rotate amongst themselves to provide four ships

for the Sixth Battle Squadron. The oldest was USS Delaware which had been completed in 1910. She was joined by USS Florida, (1911), and two pairs of sister-ships, USS Arkansas and USS Wyoming, (1912), USS New York and USS Texas, (1914). In terms of battleship development, the six vessels represented the second through the fifth incarnations of American-built dreadnoughts. All were similar to one another in layout with their main armament of 12" or 14" guns in center line turrets. Each sported the distinctive twin 'basket' or lattice masts favored by US designers. Furthermore, at a time when oil-power was gaining favor, they were all coal-burners. Although the deprivations of the U-boat campaign had robbed Britain of imported fuel oil there was no shortage of good Welsh coal. Ship for ship, the Americans could be favorably compared with their British counterparts although their crews were not nearly as experienced. Nevertheless, from their open-minded admiral downwards, they were prepared to learn.

Rear Admiral Hugh Rodman

U.S. Commander

Rear-Admiral Hugh Rodman flew his flag in New York. He took the sensible line that the Americans were there to benefit from their host's experience and that they should make the most of the opportunity offered to them. He later wrote "I realized that the British Fleet had had three years of actual warfare and knew the game from the ground floor up; and while we might know it theoretically, there would be a great deal to learn practically." Fortunately, Rodman, a genial Kentuckian, established excellent relations with Admiral Sir David Beatty, a dashing Irishman, who had succeeded Sir John Jellicoe, a cautious Englishman, as Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet. They appear to have genuinely liked one another and although at first Beatty had reservations about the true value of his ally's contribution he had sufficient political savoir-faire not to air them in public. Furthermore, he recognized the considerable effort Rodman and his subordinates were making to fit in with the Grand Fleet. The effort paid off and by June 1918 it seems real integration had been achieved and whatever misgivings Beatty had harbored earlier on appear to have been laid to rest.

Although they were actively involved in routine sweeps, convoy protection and laying the North Sea Barrage, much to their disappointment the American contingent never came in direct conflict with the High Seas Fleet. They came closest in the spring of 1918 when Admiral Reinhard Scheer took his charges out on April 23rd. for what was to be their last sortie of the war. Scheer planned to intercept a British convoy which was sailing from Bergen in Norway together with the covering forces that were already at sea. Unfortunately for the German admiral the intelligence on which he had based his plans was faulty and so he missed both that convoy and another sailing in the opposite direction. Ill-luck continued, high winds grounded his reconnaissance Zeppelins and his scouting cruisers failed to detect their prey, so that when the battlecruiser Moltke developed engine problems which necessitated her being taken under tow, Scheer called it a day and returned to base.

Although the British had been on the alert for German movements because of the Zeebrugge raid on April 22nd., Scheer had succeeded in maintaining radio silence until the Moltke incident on the 24th. Learning that their opponents were out, the 31 battleships of the Grand Fleet, including Rodman's squadron, together with their escorts, put to sea in a vain attempt to intercept the numerically inferior High Seas Fleet. Compounding the failure of the chase, the British had their own intelligence misfortune when one of their submarines, J 6, on patrol close to Scheer's route neglected to report the enemy's movements. Nevertheless, had German intelligence been more accurate Scheer's superior force could have caused a great deal of damage to both convoy and escort. (In late 1917 similar convoys had been attacked by light forces attached to the High Seas Fleet with great success.)

Ironically, if the sortie had taken place a few days earlier, the covering force for the Scandinavian convoys would have been Rodman's squadron. At least one historian has raised the question of what might have happened had Scheer left port earlier and come upon the enthusiastic but inexperienced Americans and sunk them in the inhospitable waters of the North Sea. Actions between capital ships often resulted in horrendous casualties for the losers, (at Jutland only three men out of a crew of 1031 survived after Invincible exploded), and it is fascinating to speculate on the effect such a devastating loss might have had on American public opinion. It may be recalled that at the time the AEF had yet to be involved in any major fighting and participation in the war was still something of an adventure. Equally ironically, by virtue of their station, the Sixth Battle Squadron would have found themselves in the vanguard had Beatty's pursuit of Scheer proved successful. Rodman was rather wistful when he considered this lost opportunity some years later, "I have often thought what a glorious day it would have been for the ships of our country to have led the Grand Fleet into action." Such an opportunity was not to come until twenty-five years later when his successors had shrugged off the mantle of junior partner.

As the war drew to a close morale within the High Seas Fleet worsened. Not only were the internal tensions continuing to drain the sailors' willingness to obey their officers, it was also increasingly obvious that any hopes that Germany may have had for victory on land were beginning to evaporate. By the beginning of May the Ludendorff offensives were petering out and the influx of enormous numbers of fresh American troops would place the army at a crippling disadvantage in manpower. The naval blockade had so affected the import of food and raw materials that the nation was at the point of human and industrial starvation. Allied successes in the campaign against the U-boats had finally begun to contain the most effective weapon the Germans possessed. No longer in a position to suggest peace terms let alone dictate them, an exhausted Germany was sliding into collapse. Unrest in the High Seas Fleet was heightened when credible rumours of final 'death or glory' sorties began to circulate. Scheer did not improve the situation with the declaration that "It is impossible for the Fleet to remain inactive in any final battle that may sooner or later precede an Armistice. The Fleet must be committed. Even if it is not to be expected that this would decisively influence the course of events, it is still, from the moral point of view, a question of honour and existence of the Navy to have done its utmost in the last battle." Plans for a final offensive were actually drawn up. However, the crews failed to share their Admiral's enthusiasm for what would amount to a 'death ride' and when at the end of October the Fleet was ordered to assemble outside Wilhelmshaven mutiny broke out. By November 4th. red flags flew above the Naval bases and they were under the control of revolutionary councils.

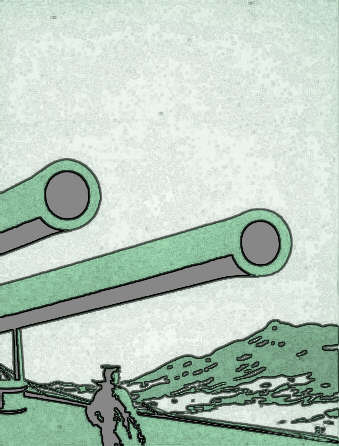

USS Delaware

As armistice negotiations proceeded, arguments had broken out amongst the allies as to the terms that should be imposed upon the German navy. Unaware of the true extent of the mutiny, and still falling prey to the notion of a final aggressive sortie, the Admiralty wanted the surrender of two out of three squadrons of Scheer's battleships and all six of the surviving battlecruisers. These proposals were met with some resistance from the American delegation who harbored suspicions that after any 'surrender' the British would simply take over the German capital ships and thus commit their navy to a far more ambitious building program than that they were already engaged upon. Not surprisingly, many in America government circles hoped that the US would emerge from the war an even stronger naval power. In the end, it was agreed that the German fleet would be 'interned' until a proper disposition could be decided upon at a formal peace conference. As no neutral nation had either the desire or the capacity to handle such an internment the British offered to accommodate their erstwhile enemies at Scapa Flow, the vast inhospitable anchorage in the Orkney Islands to the north of Scotland. This offer was accepted and when the armistice was concluded at Compiegne the Germans had agreed to the internment of 10 battleships, 6 battlecruisers, 8 light cruisers and 50 destroyers. (Under the same agreement the remaining U-boat forces were to surrender to Admiral Tyrwhitt at Harwich.)

Four days after the signing Rear-Admiral Meurer arrived in Scotland aboard the light cruiser Konigsberg to discuss the procedure. In a series of tense, highly punctilious meetings it was determined that the High Seas Fleet surrender would take place on November 21st. Given the codename of Operation ZZ the exercise soon took on the derisive sobriquet of Der Tag. In a massive show of strength Beatty and the Grand Fleet set sail to meet the Germans. 370 ships representing the cream of the Royal Navy gathered to greet their former enemies and escort them to their initial internment areas in the Firth of Forth. In the midst of this armada were the Sixth Battle Squadron under the temporary command of Rear-Admiral William H. Sims. Sims had arrived in London as a personal emissary of Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels in early 1917 and had worked closely with the Admiralty since then. A reputed anglophile, he was seen as a useful counterweight to the anglophobe Chief of Naval Operations Admiral William S. Benson. (It was Benson on the Allied Naval Council who had raised the question of the Royal Navy simply annexing those units of the High Seas Fleet it wanted.) Sims was to enjoy the same cordial and effective working relationship with his British counterparts on shore as Rodman did at sea.

Amongst the American witnesses to the surrender was Lieutenant Francis T. Hunter, aboard the flagship New York, whose lively description of the scene provides us with a colorful picture of the events as they unfolded:

"This was the day! No secrecy; no doubt. The world knew. The King himself had come but yesterday to acclaim the triumph that must be ours today. Too vast a situation well to comprehend - the German High Seas Fleet had sailed from Kiel! And the King had come. Hundreds of strangers were aboard our ships. A flush of excitement covered every face, held back by a forbidding silence that seemed to suspend the motion of the very earth.

"From early evening, long lines of destroyers had preceded us to sea, hours and hours of them, out of the misty Firth of Forth, followed by envious eyes. Every official ship that could turn a screw would follow shortly. Shortly! The hours were ages long. It was not until two A.M. that the greatest day of our lives began. The day of a thousand dreams. We seemed to be living within a highly inflated bubble, about to burst. The American flagship New York broke moor, swung slowly with the tide, felt the throbbing of her screws, fell into line to lead the Sixth Battle Squadron to sea.

"Out of the firth; out of the fog. Gray ships in a gray dawn...Great monsters rising and falling on the incoming swells, by their very stateliness acclaiming victory. At four A.M. our general alarm clanged harshly...All hands to battle stations! A few moments bustling rush - then quiet again...Each gun is manned. Every man is at his post...Range finders scan the horizon and lookouts swing their glasses in wide arcs for smoke. Three decks below the water line men sit with 'phones, tubes, boards, pencils, and strange instruments, connected with the conning tower. The plotting room. The centre of control of fire. No "Wooden Horse of Troy," for Admiral Beatty. Not the slightest chance for Hunnish trickery...He has the German guaranties - but he treats them as the Germans would, "Mere scraps of paper." Perhaps they seek to take the Grand Fleet unawares?...

USS Wyoming

"At last dawn comes, blazing red. A low haze cuts the visibility to five short miles, but the rising sun reveals a new disposition of our forces. Admiral Beatty has divided his ships into two great lines - the northern and the southern. These two lines, proceeding on parallel courses, about two miles apart, will permit the German fleet to pass down their centre. A "Ships right and left about" will then bring both lines steaming in inverted order toward the Firth of Forth, the German line between. Either of our lines, without the other, could engage the surrendering German fleet successfully." (The American Squadron took its place in the northern line.)

"On we steam at twelve knots to point "X" in the North Sea. Eight bells strikes clearly. We know the great moment is not far distant now, and the imposing spectacle are reassured. At last:

""Sail ho!" -- from the foretop lookout. "Where away?" - from the bridge. "One point off the starboard bow," in reply. "Can you make it out?" "Dense smoke, sir, seems to be approaching."

"Twenty-five minutes later, off May Island, the tiny light cruiser Cardiff, towing a kite balloon, leads the great German battle cruiser Seydlitz, at the head of her column, between our lines. On they pass - Derfflinger, Von der Tann, Hindenburg, Moltke -- as if in review. The low sun glances from their shabby sides. Their huge guns, motionless, are trained fore and aft. It is the sight of our dreams - a sight for kings! Those long, low, sleek-looking monsters, which we had pictured ablaze with spouting flame and fury, steaming like peaceful merchantmen on a calm sea. Then the long line of battleships, led by Friedrich der Gross,...Konig Albert, Kaiser, Kronprinz Wilhelm, Kaiserin, Bayern, Markgraf, Prinz Regent Luitpold, and Grosser Kurfurst...powerful to look at, dangerous in battle, pitiful in surrender...This, then, is the end for which the Kaiser has lavished his millions on his "incomparable" navy...

"Strangely enough, the German surrender lacked the thrill of victory. There was the gaping wonder of it, the inconceivable that was happening before our very eyes - the great German fleet steaming helplessly there at our side - conquered...The one prevalent emotion, so far as I could ascertain, was pity. It carried even to our great Commander-in-Chief, who I believe was the least thrilled and most disappointed person present. In speaking to us after the surrender he remarked:

"It was a most disappointing day. It was a pitiful day, to see those great ships coming in like sheep being herded by dogs to their fold, without an effort on anybody's part." And no one of his audience dissented. They were as helpless as sheep. About two hours' vigil satisfied our commanders that such was the case, and we secured battle stations. Later investigation showed that all our precautions were quite unnecessary. Not only had the powder and ammunition been removed from the German ships, but their range finders, gun sights. fire control, and very breech blocks as well. They came mere skeletons of their former fighting selves in a miserable state as to equipment, upkeep and repair. For example, in passing May Island at the entrance of the Firth of Forth, Admiral Beatty signalled one of the German Squadrons to put on 17 knots and close up in formation. The reply came to him, "We cannot do better than 12 knots. Lack lubricating oil." What chance, then, of a modern engagement where a speed of at least 18 knots is sustained? Apparently they were no better off for food. Hardly had they anchored when the crews turned-to with hook and line to catch what they might for dinner!

"Guarded on every side, the German ships entered the firth at about three o'clock quietly to drop anchor outside the nets. We stood in past them, as they rode peacefully to the tide, and on to our berths, squadron after squadron, type after type, until their German eyes must have bulged in awe at such a vast array of power. Last of all came the Queen Elizabeth, flagship of the Grand Fleet, with Admiral Beatty."

Beatty was disappointed. He had hoped for another Trafalgar, not this "pitiful" spectacle. To the end he almost hoped for trouble. If the guns of the High Seas Fleet had been rendered harmless, those of the Grand Fleet were fully loaded and trained on the German line, their crews closed up in their distinctive white anti-flash hoods. But the order to fire never came. The only casualty of the operation was the German destroyer V 30 which struck a mine and sunk during the journey from Kiel. As his Flagship steamed slowly to its anchorage, Beatty was cheered by his British and American sailors. His gold-laced cap raised in response to their praise, the admiral acknowledged and thanked them for their part in what was a hollow victory. Shortly thereafter, he sent the signal "The German flag will be hauled down at sunset today, Thursday, and will not be hoisted again without permission." Ten days after the final shots had been heard on the Western Front, the war at sea was over.

Ten more days later and the Americans sailed for home. With Rodman in charge once more, New York led the Sixth Battle Squadron out of the Firth of Forth. The four Queen Elizabeth class 'super-dreadnought' battleships of the Fifth Battle Squadron, together with the Eleventh Destroyer Flotilla escorted them on their passage. As Francis T. Hunter was to describe it: "There was music and cheering nearly all the way, culminating as we approached May Island....There was a sustained roar of cheers as the great ships parted from us, and the signal force was put to it in the rapid exchange of felicitous messages. From the masthead of...HMS Barham was displayed at the last the plain English hoist "G-O-O-D B-Y-E-E-E-E." Simultaneously a message was received by radio from the Commander-in-Chief, Grand Fleet:

"Your comrades in the Grand Fleet regret your departure,. We trust it is only temporary and that the interchange of squadrons from the two great fleets of the Anglo-Saxon race may be repeated. We wish you good-bye, good luck, a good time; and come back soon!""

USS Arkansas

The once proud High Seas Fleet did raise its ensigns again on June 21st., 1919 when in a final act of desperate defiance the rusting, neglected ships interned at Scapa Flow were scuttled by their skeleton crews. Their British guardians, who had taken advantage of fine weather to leave the anchorage for gunnery practice in the North Sea, were not amused. American warships were to return to British waters to face a hostile Germany soon enough, but not all the battleships of the Sixth Battle Squadron came with them. The veteran Delaware was stricken in 1924, Florida in 1931. Wyoming was rebuilt in the 1920's as a training ship. Some consideration was given to returning her to battleship status during World War II, but the project was never carried out. She was stricken in 1947. Her sister-ship Arkansas did see service during 1941-45. Partly modernized, she sailed as cover for Atlantic convoys and as a floating battery gave valuable support to the amphibious landings in Normandy, the South of France, Iwo Jima and Okinawa. She went on to survive destruction in the first atomic test at Bikini Atoll, but was sunk in the second on July 25th., 1946. Like Arkansas, New York saw action in both the Atlantic and Pacific theaters and ended up at Bikini. However, she survived both tests and was towed to Kwajalein and decommissioned. She was then taken to Pearl Harbor but proved too radioactive to have her fittings removed and so was sunk as a target in July 1948. After service in company with Arkansas and New York once more, Texas finished her career as a fighting ship and went on to enjoy a far less traumatic end; she became a state war memorial in 1948 and is the sole surviving US battleship of the dreadnought era. She is at anchor in the Houston Ship Channel and is being restored to her 1945 configuration and colors.

|