The Story of the American Expeditionary Forces |

General Headquarters AEF |

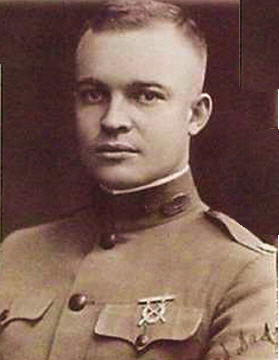

Major General Fox Conner: Soldier, Mentor, Enigma:

|

In 1987, the name of Major General Fox Conner was added to the Mississippi Hall of Fame. Mississippians from Corinth to Gulfport and from Vicksburg to Hattiesburg certainly had a right to collectively scratch their heads and ask "Fox who?" Indeed, few Hall of Fame inductees ever achieved their exalted status the way Conner had. This man had never achieved fame outside of his chosen profession. He was seldom quoted and never interviewed. Much to the biographer's frustration, Conner wrote neither book nor memoir, subsequently leaving nothing that would detail a storied and well-traveled career that would span forty-four years of military service. Contemporary memoirists seldom offered readers his name and never in association with the salacious tidbits of some juicy memoir. Yet even after a lifetime of correspondence with his immediate family, years before the electronic era, only twenty-eight of his letters survive. The consummate family man, he could be the loving and devoted husband as well as the protective and doting father of his children. At times he could be ebullient and quite profane. George Patton, often invited to go hunting with the General in the Adirondacks, described his outbursts upon missing a shot as "novel and innovative." Publicly, Fox Conner was an articulate and consummate military professional. When out of uniform he was a relaxed gregarious and very private man. Following the First World War, Conner served in a variety of positions that would certainly not attract much public attention outside the military itself. Yet, without the counsel, influence and timely personal interventions of this little known staff officer from Mississippi, a culmination of events in Dwight Eisenhower's early inter-war assignments would have certainly brought his military career to either inglorious termination or at worst, disgrace. This Mississippian's mentorship has been described as instrumental in the professional development and preparation of the young major from Kansas destined to be the future Supreme Allied Commander and later President of the United States. FOX CONNER: THE ENIGMAFox Conner is an enigma. Not surprisingly, it is because of the dearth of personal information he left behind. His insistence of giving credit to future famous subordinates, the maintenance of a very private life, and his retirement on the precipice of the unthinkable; Europe at war a second time in twenty years overshadowed the achievements of the AEF in the "War to End All Wars." Nearly every professional journal article and biographical sketch written about MG Conner, since his death in 1951, contain glaring inaccuracies, incorrect chronology and unfortunate factual error that concern his early life through his inter-war service. The purpose of this paper is to seek the intersection of MG Conner's verifiable biographical details with his achievements and, within space limitations, attempt to correct the assertions of his current biographers. Biographical sketches written by LTG Sidney Berry, Charles H. Brown , Cole Kingspeed and a recent article published in Military Review by Professor Jerome H. Parker 4 are all unfortunately flawed with either factual error, confused historical or incorrect career chronology. Even greater confusion exists among all Conner's biographers when detailing the Conner-Eisenhower relationship. Author Carlo D'Este offers differing dates of Conner's fateful first meeting with Dwight Eisenhower. The late historian Merle Miller over-emphasized the nature of Conner's post-war assignment in Panama. Both Miller and D' Este misdirect their readers in locating Camp Gaillard, Panama. Most importantly, almost all of the cited writers fail to fully appreciate Conner's AEF contribution when writing of the planning and execution of the Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne offensives. As if to underscore the frustration that any biographer would have in attempting to "find" MG Fox Conner, Professor James J. Cooke's monumental "Pershing and His Generals: Command and Staff in the A. E. F.," billed as the definitive work on Pershing's inner circle at Chaumont, has Conner's name, throughout his entire volume, misspelled.5 To be fair, it could be demonstrated that it is MG Conner's own fault that he confounds any modern biographical study. While at the height of his career he never sought publicity and rarely found any. Conner was publicity shy, unlike his pick for First Division Commander, the hero of Cantigny, MG Robert Lee Bullard, whose photograph once appeared in a 1921 issue of Collier's magazine, in full uniform, advertising the health benefits of Lucky Strike cigarettes. Neither Conner's son nor daughter left any substantial written recollections of their father. Unfortunately, they contributed only a few comments regarding their father's relationship to Eisenhower. In the 89 years since the Great War ended, not one monograph has ever been produced offering a critical study of the accomplishments of Fox Conner. It is only from Virginia Conner's small and rare volume of published memoirs, and to a few of Eisenhower's own candid recollections, that one is offered a personal glimpse into MG Conner's personality and professional life. Unfortunately, while Virginia Conner's volume contains many entertaining anecdotal observations from the viewpoint of a cheerful, vivacious, name dropping, prohibition flaunting yet dutiful career military wife, the work lacks essential chronological continuity and critical objectivity. The book is frustratingly short on many of the many essential details scholars and biographers require of her husband's life.In 1938, MG Conner, retired completely without fanfare. Throughout the Second World War, despite his mentorship of the greatest American military names of the day, he continued to shun newspaper interviews, unlike his old AEF commander, and lived out the remainder of his retirement quietly and unobtrusively. After a prolonged decline in health, General Conner died in 1951, in relative obscurity at the age of seventy-eight. Even without a published monograph, this intelligent, insightful and competent officer was held in the highest esteem of his contemporaries. He was not only a competent military historian, but also a brilliant military war planner and strategist as the chief architect of the American victories at Saint-Mihiel and the Argonne in 1918. A serious military science intellectual, Conner's series of War College lectures in the 1930's integrated critical yet sagacious observations of lessons learned by the AEF in the Great War and some that the army had yet to learn. While proposing a structure that an Allied military coalition for the future must resemble in order to be successful in the coming European conflict that he often predicted, Conner established a theoretical and constructive framework not for an Allied Generalissimo but a Supreme Allied Commander. He was the chief advocate and a founding father of the inter-war re-configuration reforms of the modern American infantry division that eventually marched into Europe a second time, long after he had retired. Concomitantly the General spoke forcefully against the inadequate replacement system of the Peyton March period, and successfully won the necessary reforms that saw service in the Second World War. Not only does MG Conner's critical role and achievements while serving on Pershing's staff deserve long overdue recognition, moreover his personal dedication and influence supporting the career development of many of the new breed of army officers who would become household names as they later fought the Second World War. His most notable pupil was Dwight David Eisenhower. Upon further reevaluation, MG Fox Conner emerges as the most influential officer intellectual in the United States Army during the inter-war period. Conner's contributions to the United States Army can be evaluated in three capacities. First, as G-3, chief of war plans and operations on the Allied Expeditionary Forces staff in the First World War, Conner was the senior architect of the Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne offensive. Secondly, as the general commanding the Army's most important inter-war assignments; and, thirdly, as instructor, military scientist, lecturer and personal role model for younger officers in the lean army career years of the 1920s and 1930s. According to Eisenhower, "Outside of my parents, he had more influence on me and my outlook than any other individual, especially in regard to the military profession." Eisenhower would later deem as prophetic Conner's poignant observations regarding Allied political decisions that allowed German military forces to march back to the Fatherland, unmolested following the armistice, carrying their arms with bands playing and flags flying. Conner predicted that a myth would be born inside Germany that the Imperial German Army had never really been defeated by the Allies, but rather been traitorously stabbed in the back at home by fifth columnists. This was indeed the myth that Adolph Hitler and the National Socialists would expeditiously exploit in order to seize power. Conner, said Eisenhower, warned that a lasting peace had been doomed at Versailles by accepting the principle of a negotiated peace rather than a dictated peace and "in the not too distant future the whole job would have to be done again." Conner was dismayed at the determination of the allies in 1919 to exact a punishing revenge on Germany within the terms of Versailles Treaty, and yet, fail to foresee dire consequences ahead. As Conner told Eisenhower in 1922, "You can't take the strongest and most virile people in Europe and put them in the kind of strait jacket that this treaty attempts to do." EARLY YEARSAs Eisenhower described him, "He was never the hard or high pressure type. He had the mind of a steel trap, but gave the appearance of being leisurely. He was sort of drawly . . . came from Mississippi, you know . . ." Conner evidently inherited all the regional nuances of his southern birthplace. The word Negro became "nig-rah" and "fixin" usually, meant the word "preparation" and "hay-ed" for head.Fox Conner's ancestral roots run deep in the sandy, scrub pine-wooded hills of northeast Mississippi. At the time of his birth, he was the third generation of the Conner family who had come with the first settlers of what is now Calhoun County. Road systems were not established as the Conner clan arrived in the 1830's, but flat boats and keel boats still navigated Calhoun County's two rivers bringing in supplies and shipping out cotton bales from all parts of this rural Mississippi county. Born to Robert Conner and Nannie Fox in Slate Springs, Mississippi on November 2, 1874, Conner was educated in the poorest of the public schools of rural Calhoun County. The school system was unremarkable for producing any more than future gin-mill employees and barely literate farmers and Conner had no intention of following a mule down a furrow for the rest of his life. Not much is known of the character of Conner's parents. However, a reference written by, Virginia Conner, many years later is quite telling. Conner's aunt had warned the newly wed Virginia to use caution around her brother, Robert, as, "Fox's father would not stand the slightest contradiction on any subject." A surviving letter from Fox to a cousin on the occasion of Nannies' death describes her dutifully as a, "sainted, quiet loving Christian woman." Then, as now, the military offered an escape for a rural youth with bleak prospects at home. To a fortunate few, what transforms a bleak prospect into a promising future is the intervention of a rich uncle, and Fox Conner apparently had one of those. Fuller Fox, a maternal uncle, was, according to family tradition, every bit a self made man. He was a wealthy but genteel Mississippi mogul, with a lucrative gin mill and considerable real estate interests. More importantly, he had the ear of the senior senator from Mississippi, a post-reconstruction politician with the unlikely name of Senator Hernado De Soto Money. While in the family tradition Nannie Fox is given the credit, it is Fuller Fox who actually approached Senator Money, while, fortuitously, on the campaign stump in north-east Mississippi, and offered his poorer-relation as a candidate for one of the two vacancies that the Senator must annually fill at the Military Academy at West Point and the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis. Having the requisite political connections to make his escape to an exciting military career was one thing. Convincing his father, who while fighting for the Confederacy at the Battle of Shiloh in 1862 had been permanently blinded at the age of seventeen, was quite another. First things, first, however. Conner would have traveled to the capital city of Jackson to take the requisite battery of written examinations as well as the physical. Though no written account survives, the journey certainly would have been an eye opening experience with an extraordinary amount of rubbernecking while enroute, indicative of an untraveled youth from the jack pines. All that remained was to convince his father. Again, though no written account of his father's reaction has survived, Robert Conner did not need the gift of sight to see what the future might hold for his son if he remained beyond high school in Calhoun County. Robert gave his blessing. The senatorial appointment was not unexpectedly forthcoming and on June 15, 1894, Fox Conner took the oath as a new cadet on the Plain at the United States Military Academy at West Point. Robert Conner certainly could have had no idea that his son was embarking on a military career that would span forty-four years and take him from second lieutenant to major general, which was, at the time of his retirement, the highest permanent rank in the U. S. Army. Conner's record at West Point is admirable but not academically stellar. He excelled in history, mathematics and horsemanship. He won a medal for French and played outfielder on a championship Army baseball team. That a rural Mississippi farm boy, with only a rudimentary secondary education would so excel in collegiate level French, that it would have a profound impact on his service to his country and his subsequent career, is the stuff that high school French teachers can only dream of. Demerited only eleven times in four years, this commendable achievement undoubtedly brought him to the positive attention of his class tactical officer, Captain John J. Pershing, a dour, humorless officer, who appreciated discipline and minute attention to detail from his cadets. He graduated in the top third of his class, seventeenth in a class of fifty-nine. Unlike Eisenhower's class of 1915, dubbed, "the class the stars fell on," because of the number of general officers that were to come from its ranks, Conner's Class of 1898 graduated only three future general officers, of whom, he was destined to become one. New military technologies like, belt-firing, water cooled machine guns, tanks, aircraft and radio communications might have been waiting just around the corner in the new century, but for Conner, it might as well have been 1861. He was commissioned a second lieutenant of artillery and, after a basic course in direct-fire gunnery, using the old 3-inch Ordnance Rifle, was assigned as a gunnery officer in the horse-drawn batteries of the 2nd U. S. Field Artillery. CUBA AND MISS BRANDRETHSent to Cuba, in 1899 as part of the American occupation force following Spain's defeat, Lieutenant Conner was assigned to administrative duties with General Fitzhugh Lee's headquarters in Havana. The duty was anything but interesting. The one bright spot during his tour of duty was his chance meeting of the young and vivacious Miss Virginia Brandreth of Ossining, New York. Virginia was the daughter of a wealthy Empire State pharmaceutical and real estate mogul. The ancient Dutch family name of "Brandreth" was given to a mountain, and many thousand acre forested valley in the Adirondacks, that was granted to an ancestor following the American Revolution and was still a favorite family gathering place into the late 1980's.Virginia's uncle, Captain Herbert Slocum was the son of famed Union Army artillerist, Henry W. Slocum, who not only had been Sherman's choice to command the XX Corps in The March to the Sea, but had also been, like his son, commissioned in the Second Artillery. The younger Slocum was also on occupation duty in Havana. The tropical assignment was pleasant enough for Slocum and his wife to offer an invitation to their precocious, and often restless, young niece for an extended visit to Cuba. Her father naturally objected to the young twenty-two year old woman making such a long trip unaccompanied but the opportunity to leave the less than stimulating surrounds of upstate New York for the exotic city of Havana was too much. Virginia insisted on making the visit. "Luckily I came down with a bad cold that left a cough and my mother finally persuaded him that she thought the warm climate would cure me. I helped as much as I could by giving the most nerve-racking whoops whenever he was around, and they had to be loud and furious as he was very deaf at the time." Her father relented based on her "precarious" condition and she was allowed to make the journey. It was during this visit that Virginia met 2LT Fox Conner. Virginia writes, " In Cuba all of the girls had been intrigued by a man called Fox Conner, the woman hater. He was very popular with his fellow officers but spurned female society . . . He was to pay dearly for his aloof attitude . . . it was a planned attack . . . . " The couple met again the following year at Washington Barracks, later re-named Fort McNair, and Virginia resolved that, " . . .if he refused to meet me I would sprain my ankle and fall at his feet. There were times when a weak ankle on a girl could prove useful." Though Virginia did not have to employ such a drastic tactic, there is little doubt she would have resorted to the measure if the situation had called for it. At a welcoming tea for newly assigned officers' wives, of which Virginia's Aunt Bird Slocum was one, she was officially introduced to Lt. Conner. She was then twenty-three and he was twenty-six. According to Virginia the meeting was love at first sight and within a year culminated in their engagement and subsequent marriage in 1901. Once more, Virginia gives a hint, but nothing more, as to how relations must have been with her newly acquired Mississippi in-laws, "As Fox's family had completely ignored me, I imagined they were horrified that their son, a dyed in the wool rebel, was to marry a Yankee." Conner's first assignment after his marriage was as executive officer of a coast artillery battery at Fort Hamilton, New York. Conner wasted no time on the bright lights of New York City. When not involved in the physical repairs of the much-neglected post, Conner was busy studying the art and science of gunnery and fire-direction. Fire direction took a new meaning, when, on an evening in December 1901, a destructive and fast burning fire consumed half of the old post and, though they escaped the blaze, Conner and Virginia were forced to move to new quarters several blocks away. Destructive fires in turn of the century dilapidated wooden military structures were not uncommon and usually were deadly. One such fire claimed the lives of John Pershing's wife and three daughters. Conner's two published articles in the Infantry Journal demonstrated a grasp of the new science of indirect fire artillery working in support of attacking infantry formations. This article evidently drew the attention of key members of the army hierarchy who caused him to be assigned twice, first in 1907 and again in 1911, to the faculty at the Army Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. How much respect this company grade officer received from his field grade students can only be guessed. A clue is offered from Conner's remarks in 1911, that he found "teaching officers much older than himself something of a strain." In 1911, the War Department had accepted the invitation of the French Military Attaché to send an American officer to serve with a French artillery regiment for a year and then attend the prestigious L'Ecole de Guerre in Paris. The Army began to comb personnel files to identify the relatively few French speaking American officers on active duty that could fulfill the requirements of completing the tactical assignment with the French artillery while intelligently recording the organization, tactics and logistics utilized in modern European army field operations. Although Conner had been offered his choice of positions as military attaché to either Turkey or Mexico, he declined them both and accepted the coveted assignment to Paris. At the time he could not have foreseen how soon, and how desperately, the ill equipped U.S. Army needed the expertise he would gain in France. The mission and the man were well suited. Conner and his growing family of wife and now two children sailed for Paris in July 1911, finally settling in at the Villa les Violettes, 6 rue Deschamps, Versailles. While Virginia busied herself finding appropriate tutors for the children and managing an overseas household, Conner spent the year 1912-1913 training with French artillerymen, becoming acquainted with the capabilities and limitations of different caliber French guns. He noted the training regimen of French artillery officers and NCOs as well as the novel indirect artillery fire control procedures. The time spent was invaluable. He developed insights, contacts and instituted relationships that would prove helpful in the fateful coming years. Conner's knowledge of the French language and his insight into the political machinations of the French Army would prove crucial, especially when acting as the secondary interpreter for Pershing during the "table pounding sessions" with the French General Staff. Unfortunately, the assignment ended before Conner could begin the artillery officer's course at the L'Ecole de Guerre. U.S. War Department regulations had recently been revised to ensure that an officer was getting enough line assignments in his career. Thus began the curiously named "Manchu law" that required an officer to spend two years out of every six in a troop unit assignment. Since Conner had been on detached academic service for the last five years he was obliged to become "Manchued" home and trade his newly acquired apartment overlooking the left bank of the Seine for the less scenic vistas surrounding Fort Riley, Kansas. Fort Riley, in 1913, was the home of the U. S. Army Cavalry School and was in a state of combat alert when Conner and family, now with three children, arrived. The Mexican government of Francisco Madero was overthrown and the president murdered the latest in a series of violent revolutions. General Victoriano Huerta had seized power and imprisoned Madero's supporting bands of regional warlords, one of whom in the north was named Dorteo Orango, known forever to history as Pancho Villa. Narrowly escaping execution, by sawing through the bars in his cell, Villa returned to his scattered forces based in Chihuahua. Villa's new Division del Norte succeeded in routing Huerta's federales in Chihuahua and he ruled over the largest of the northern Mexican states like some unlettered medieval baron. Financing his army by stealing from the endless cattle herds in northern Mexico and selling the beeves north of the border, Villa found plenty of unscrupulous American merchants merchant's willing to sell him guns and ammunition in return for cattle on the hoof. The border area was feeling the instability and rumors were continually flying as to Villa's whereabouts. Acting on a rumor that Villa was making a forced march against El Paso, Ft. Riley was alerted and Conner was sent to the border as a battery commander with the 6th U. S. Field Artillery. Conner and the horse-drawn three-inch guns of the 6th made their headquarters at Laredo, Texas. The many rumors of Villa's movements, while turning out to be false, did little to relieve tensions between the United Sates and Mexico. General Huerta's government had managed to provoke the unusually ambivalent and pacific Wilson administration by threatening to unload a cargo of German munitions at Vera Cruz. Armed U. S. Marines and sailors fought Huerta's troops into the custom's house and prevented the munitions transaction from taking place. Villas brazen attack on Columbus, New Mexico brought thousands of new recruits into the service and Captain Conner was ordered to join the faculty at the U. S. Army Artillery School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. The assignment appears to have been unremarkable. Confounding future sleuths of archived officer evaluation report narratives, searching for tidbits of personal accolades or shortcomings, Conner's officer evaluation report for 1914 reveals only that Captain Conner is " a serious soldier and a technically proficient artillerist." In July 1914, still smarting from having to move from such prime property in Paris, Conner had re-applied to attend the L'Ecole de Guerre. In September 1914, the second year of his tenure at Ft. Sill, Conner was ordered back, to now war torn France, as a neutral military observer. Conner had also been concurrently assigned as one of the four American military observers to France. Virginia Conner writes that, in spite of the war, the couple was overjoyed at the opportunity to return to Paris. Fate apparently would have none of it. No sooner had he departed Fort Sill on the train for Washington than he felt himself becoming ill. By the time the train arrived at Union Station in Washington, Conner had nearly died from what was found to be a ruptured appendix. Virginia Conner remembered, " I started east with the three children, expecting at each station to hear that he was dead and I was a widow, but when I reached Washington, he was still holding." Having lost the French assignment, and following a lengthy recovery at Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington, Conner was ordered to report for duty with the Army Inspector General's office. It was in this capacity as the IG for Field Artillery that, in 1916, he would be reunited with his old West Point tactical officer, and commander of the Punitive Expedition, now a major general, John J. Pershing.  Pershing and His Headquarters Staff, Conner to His LeftConner was soon appointed chief of operations. "As Chief of G-3, which had to do with strategy and tactics and all battle action, his was the problem of how to hit the enemy harder than he hit you with more cost to him than to you." Most of Pershing's higher staff officers were graduates of Fort Leavenworth's Staff School, which on the one hand was a blessing as "they showed a common passion for precision planning, clear orders, simple movements and care of the troops." However, later in reevaluating his G-3 section at Chaumont, Conner would be critical of the culture of the schoolhouse answer. "At our schools we had very good courses in tactics. Our studies in history had led, for the most part, to sound strategic ideas. But our technique was practically limited to making a fetish of the five-paragraph order; and paragraph 4 (logistics) was very sketchy at best. We forgot, ignored, or rendered lip service only to the most important of all Napoleon's maxims; namely, an Army moves on its belly." According to Conner, the immediate tasks confronting the G-3 section were accurate studies of the forces required, the organization of these forces down to regimental level; artillery, other major equipment and where to locate them; ports of debarkation, lines of communication, zones of operation and safe training areas. Conner later remembered, "To arrive at a proper conclusion, all of these matters had to be discussed with the British and . . . solved with agreement of the French." All of the AEF staff organization had to be constructed from the ground up. "G-3 recognized . . . that organization and system are stronger than individuals but in the early days personnel and time were inadequate . . . our organization was gradual." Conner solved the problem by dividing the section into committees whose duties were indicated by their titles at Chaumont: Combat-Organization and Equipment; Troop Movements; Maps and Order of Battle; Aviation; and Liaison (Allied intelligence). These committees originated and handled all assignments received under their various classifications. Conner insisted that each section maintain communication with the other groups so that none worked independently, unconscious of how they fit in the grand scheme of the organization. Conner stressed the need for coordination in planning operations. His methods could be described as a clear demonstration of achieving organizational effectiveness through synergy. Conner threw himself into his work. By insisting on long duty days and an unrelenting work schedule that might have killed a younger man, Conner tirelessly poured over notes, battlefield reports, situation briefings, intelligence briefings and countless maps acquired from his several meetings with his French counterparts. His staff, initially limited to two officers and two NCOs, would grow to a solid Leavenworth trained group of officers. These Leavenworth trained officers were the core of competence in the AEF. However, when the United States decided to enter the war in 1917, there were only about two hundred available for duty, hardly an appropriate number of skilled tacticians in which to begin offensive operations in Europe. Further, Pershing's insistence that they all be assigned to his headquarters at Chaumont and in the subordinate combat units, caused staff preparation to suffer back in the U.S. Certainly, Conner and George Marshall proved their value in the G-3 section but such men were too few in number. In the autumn of 1917, Conner began to write the A.E.F.'s operations and training doctrine that addressed the plethora of tasks in preparation for battle in the St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne area of operations. G-3's staff would include men like Hugh Drum and Marshall who Conner trained and insisted that they act together with a common body of knowledge. Conner's staff was breaking new ground. There were no historical precedents for such American operations, nothing to fall back on. They were writing plans from scratch. CONNER AND THE SAINT-MIHIEL PLAN To the Front: American Troops Advancing in the St. Mihiel SalientConner supervised the coordination, movement and placement of the two-thirds of a million men who would use this mass of materiel. Some 560,000 American and 110,000 French troops moved into position around the salient. Conner gathered troops from all points of the Western Front; from the BEF, from the Chateau-Thierry area, from the Vosges. Against the German salient, Conner had assembled four corps, composed of four French and eight and one half U.S. divisions. Conner's meticulous planning demonstrated, from an early date, a grasp of organizing assets, coordinating logistics and planning operations while at the same time developing mutually acceptable working relationships with other key members of the Expeditionary Force staff. With certain officers, the relationships would become critically dependent. One such association was with Brigadier General Dennis Nolan. Unlike his boss, Nolan hardly looked a soldier. Nearly Pershing's height, with a thin face and sporting round spectacles, Nolan looked every inch professorial. The son of poor Irish immigrants to New York, he was indeed a professor, of history, at West Point, for the academic year 1902 to 1903. However, looks can be deceiving. Nolan had been twice decorated for gallantry in combat during the Spanish-American War and had seen service in the Philippines as Pershing's adjutant general. Assigned to Washington, Nolan was selected to serve, in the intelligence section, on the first General Staff. While on board the S.S. Baltic en route to France, Pershing selected Nolan as his G-2, Intelligence Officer. Conner certainly appreciated Dennis Nolan, who, as the harried G-2, went about the task of building the AEF intelligence infrastructure from nothing. Every piece of written doctrine, including the handling of all aspects of combat intelligence, prisoners of war, aerial photography, accurate mapping, interrogation techniques and relevant intelligence training had to be written. Most importantly Nolan needed new intelligence officers to be effectively trained and sent to all assigned AEF divisions. Accurate maps were most important. By the spring of 1918, Conner relied on Nolan for all expertise on every map as well as the posting of battlefield situation maps that displayed accurate enemy dispositions, order of battle, movements along the Allied front lines, AEF situational progress, with as close as one could get in 1918 to "up to the minute" American unit locations. Perhaps what contributed most to Nolan's value was his insistence that his commander would never be caught short of information when dealing with the AEF's problematic allies or when making timely critical decisions. Chief of staff, James G. Harbord set the policy that Nolan, and only Nolan, was to be permitted immediate access to Pershing when he needed it. This unprecedented access to the Commander-in-Chief made Conner's relationship with Nolan critical. Between Conner and Nolan lay the task of coordinating and preparing the St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne operations. Together, their staff's would coordinate the massive amounts of assets needed. All infantry, artillery, aviation, armor, engineer, poison gas, flame thrower assets controlled by Conner would enter the combat area at a specific point because Dennis Nolan said the enemy was there, and was convinced that, "there" they could be defeated. However, the most important relationship Conner would cultivate, if he were to keep his job, would be with James Guthrie Harbord, who acted not only as Pershing's chief of staff but also his eyes and ears. Conner's ability to remain politically acceptable to his Commander in Chief was paramount. This was no small task. Pershing was at best a difficult personality for any subordinate. He had no time for those he considered self-serving. He detested the toadie and was impatient with the smooth talker or the intellectually dull. He would not hesitate to dismiss those whom he felt did not measure up to his standards of loyalty, bravery or physical stamina. Scarred by personal tragedy, his wife and three daughters were killed in a fire at their home at the Presidio in San Francisco, he could be dour, at times unreasonably strict and completely lacking in humor. Photographs of a wartime smiling "Black Jack" Pershing are exceedingly rare. Conner was, nevertheless, fortunate as he was always considered a favorite within the "inner circle" of staff officers at Pershing's headquarters at Chaumont, while gaining the enmity of those that were not, principally, Douglas MacArthur. Because of the high personal standards that Pershing set for his officers, not incurring the C-in C's wrath was often difficult. At times, the slightest transgression might earn the embarrassed offender the dreaded one-way ticket home. THE MEUSE-ARGONNEPershing demanded more than just competent staff work and Conner responded. While sailing with Pershing to France on the Baltic, Conner, in charge of Plans and Operations (G-3), had put his finger on the map at a particular salient in the Meuse-Argonne where the Germans had been left undisturbed since 1914. Conner discussed the area with Pershing and recommended that along this part of the allied line is where the Americans should establish their sector and, when ready, take to the offensive. Conner had, in the meantime, designed and organized the divisions to do the job. The first of his planned divisions-the First Infantry, was the first to go into a sector with a French corps and then into the line. It's important success at Cantigny had been attributed to its fiery commander Major General Robert Lee Bullard and the staid Lieutenant Colonel George C. Marshall, the G-3, (Plans) who would later become Conner's assistant at AEF Headquarters. Conner pulled together a team of other skilled and brilliant technicians including, Hugh Drum, Stuart Heinzelman, Walter Grant and Xenophon H. Price. From all accounts, Conner was a demanding chief whose meticulous attention to the planning of A. E. F. operations set high standards for all the American division staffs. In one form or another, nearly every American action of the war came under Conner's purview and influence. Two Images From the Argonne Campaign Showing the Logistical Challenges: |

Dwight Eisenhower During WWI |

There was more trouble. In September of 1921, Eisenhower was suddenly being investigated by the inspector general's office on information that he had defrauded the government by receiving an unauthorized dependent housing allowance while his dependents, Mamie and son, Doud Dwight, were vacationing during the summer months of 1921. The amount in question was $250.67. Eisenhower had inadvertently blundered into these charges while testifying for another officer similarly charged, stating that not being familiar with the regulation, he too had believed he was entitled to and had accepted the allowance. Within days of his well-intentioned testimony he was being read his rights.

These charges were especially hard to take since they came only months after a devastating tragedy had struck the Eisenhower household. Upon her return from the vacation in question, Mamie had hired a local young woman as a maid. Because of the nature of her work, she had come in close contact with many families and unwittingly, she had also carried scarlet fever into the house. Within a few weeks of contact, young, three-year old Doud Dwight had fallen ill with the disease. The worried parents summoned a consulting physician from the Johns Hopkins Medical School in neighboring Baltimore who verified the initial chilling diagnosis. In this era, before most childhood diseases like this one were conquered, he is reported to have told the boy's parents, " We have no cure for this. Either they get well or you lose them." Within days of his visit, the child had died. Consider Major Dwight Eisenhower. Within a year of a war ending in which he has pleaded to, but is not allowed to, participate; he is called to Washington and threatened with a court martial, by his branch chief for publishing a scholarly article advocating a role for tanks. Next, his precious and only son dies suddenly and tragically at Christmastime. In the wake of the boy's death there is no sympathy from the stoic martinets who zealously guard army regulations. The Army IG, Brigadier General Eli Helmick writes in a endorsement to higher authority that a reprimand from his commanding officer, Brigadier General Samuel Rockenbach, Pershing's former AEF Tank Corps commander, is not enough: ". . .His (Eisenhower) Commanding Officer has not met the disciplinary requirements in this case . . . Major Eisenhower must be appropriately reprimanded by competent authority." Helmick wants a court-martial. A lesser man, suffering with these frustrations: what appeared to be a dead end in his career; seeing the army, the only institution he had ever known all his adult life, slide into its inter-war nadir; and, experiencing the nightmare of all young parents, the death of his only child, might be forgiven for, simply and forever, walking away. However, as historian Merle Miller correctly pointed out, General Helmick was not a stupid man. He obviously realized that the pursuit of Eisenhower and the resultant trial could well end this officer's career. He also had to consider that this officer was in the beam of a powerful spotlight. Pershing had been selected over his archrival Peyton March, as chief of staff of the army. Helmick, as a March appointee, suddenly found himself on the wrong side of the political fence with six long years to retirement. If there was to be any possibility of Helmick wearing another star at his retirement ceremony, he certainly didn't need to run afoul of this new army establishment, which meant Conner and which also assuredly meant Pershing. Conner applied pressure. Immediately upon Pershing's selection, he sent the following curiously concise memorandum to his old commander:

|

Subject: Request [from] Conner for Brigade Adjutant He desires the detail of this particular officer (Maj. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Inf.) because he knows of his efficiency and because he is due for Foreign Service. Signed, Conner |

Helmick was now cornered. There was no possibility that he simply dismiss the charges as that would be an admission of an error on the Inspector General's part. So, on December 14th 1921, Helmick, with retirement in mind, penned the most political about-face of the inter-war period. He reiterated that the 104th Article of War made no provision for a commanding officer to merely reprimand a subordinate for such a grave offense. Therefore an oral reprimand was quite out of the question. Major Eisenhower was charged with offenses of the "gravest character." Yet a trial was not to be recommended. Helmick wrote that while Eisenhower's claims for the dependant allowance were "false and fraudulent" and his claim that he had been unaware of the law governing dependent commutations was "totally inexplicable" his lack of knowledge that his claims might have been fraudulent, must be weighed heavily in his favor. Helmick then directed that Eisenhower be reprimanded by "competent authority." That authority was given to the Assistant Chief of Staff, Brigadier General J.H. McRae, whose office in the War Department was immediately adjacent to Fox Conner. A less than mild written reprimand was duly issued, Eisenhower's name was taken off the "flagged list" and orders were immediately cut to join Conner in Panama with a reporting date within the second week of January 1922. The entire "dependant allowance" episode had consumed six months of time and cost the cash strapped inter-war army far more than the $250.67 Eisenhower had unwittingly drawn. In 1952, when candidate Eisenhower was criticized for having no political experience or acumen, Eisenhower countered by stating, "I have been in politics . . .there's no more active political organization in the country or in the world than the armed services of the United States."

THE PATTON-CONNER CONNECTION

During those disheartening months at Fort Meade, George Patton, with several children of his own, deeply sympathized with his grief stricken friend and colleague and made every effort to provide the Eisenhower's with some pleasant and, much needed, social distractions. Reliable evidence points to a first meeting between Eisenhower and Conner in February of 1921, when Eisenhower, together with his wife, were''' invited to a Sunday dinner at the George Patton's where the Conner's were the honored guests. During the summer of 1920 George Patton had become reunited with the General, not having seen him since the end of the war. He and wife, Beatrice, had rented a houseboat and had invited the Conner's, sans children, to a tarpon fishing expedition departing from Captiva Island in the Gulf of Mexico to Key West. The expedition is described as "most pleasant" for both couples. Virginia Conner memorialized the trip with a photograph of a very bleary eyed and exhausted George Patton standing beside a 320-pound Jewfish that he had spent one entire night fighting and finally landed. And so it was that an invitation was proffered to the Eisenhower's to attend dinner at the Patton residence; to dine and meet General and Mrs. Conner on, a Sunday in February 1921. Patton had told Conner about Eisenhower's intercontinental motor transport experience and his consuming interest in tanks. At this point, the biographers tend to make much about Conner's prescient direction that the Army Tank Corps must take to fight a future war and that Eisenhower's keen interest in tanks had aroused Conner's further appreciation of meeting yet another proponent of tank warfare. Finally, they fully agree that, as a consequence of Patton's recommendation, Conner wanted such a man for his executive officer assignment in Panama. Careful examination of the historical record reveals, however, such statements are suspect. MG Conner was never the proponent of mechanized or tank warfare as his many would-be biographers claim. In fact, his views on "motorization" were only slightly different than Eisenhower's nemesis, the Chief of Infantry, Brigadier General Charles Farnsworth. Although Conner believed that while tanks should be in a separate branch outside of the Infantry, they could only be marginally useful. Tanks would never be produced in great enough quantity to be strategically useful. The current state of armor technology, being what it was, tanks were not seen as reliable or heavily armed or armored enough to conduct the tactical operations that Eisenhower and Patton had proposed in "A Tank Discussion." In late 1931, Conner was instructing students at the War College that ". . . everything with the exception of staff cars in the division should be animal drawn." When asked if he would use tanks in the next war to overcome the lethally effective machine gun position, he stated unequivocally, "I don't think tanks have any place in the (infantry) division . . .there will never be enough of them . . . although I was on the Board that reached the compromise on the present division, I am sorry I ever signed. Tanks and aviation were two things I was desirous of getting into the division, although I now think it was a very great mistake. I can only justify myself by the old adage, the gist of which is that "consistency is a virtue of little minds."As late as 1933, Conner was still opposed to the use of tanks against fixed positions during the advance. Instead, he proposed to War College students the use of more lethal artillery fires and heavy machine guns, parroting the accepted post-war Pershing doctrine.

Further, while Patton's personal recommendation of Eisenhower may have been helpful, the assignment to Panama did not require a tanker. Patton's referral of a tank proponent colleague for an assignment where there were to be no tanks, could hardly have weighed heavily in the General's decision making. Conner would command a Puerto Rican infantry brigade that guarded the center of Panama Canal Zone. Most of his time would be spent inspecting fortifications along the Brigade's sector of the Canal on horseback. Conner's biographers note how the general left Patton's quarters very impressed with Ike's thorough answers to his often direct and pointed questions. But Conner's appreciation of Eisenhower was probably just as much personal as it was professional. Many more would be charmed by Eisenhower's " easygoing manner and charming smile, a disarming facade that masked a brilliant, ambitious officer who thirsted as deeply as Patton did to advance his chosen career . . ." Eisenhower was young, energetic, and amiable. Using a talent that would serve him so well, in the years to come, Ike simply "schmoozed" him. Conner often spoke of "the young men needed for the next one." In Eisenhower, Conner saw a likable, eager young officer available for the "next one;" an officer that he could groom. Conner undoubtedly needed an executive officer with whom he could get along, and Eisenhower fit the bill. The fruits of that February luncheon became apparent when Conner telephoned Ike later in the same week and asked him if he would like the assignment as his executive officer in Panama.

CAMP GAILLARD

When Conner and Eisenhower arrived, the post was home to Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 20th Infantry Brigade, one regiment of the 42nd Infantry Division of the Puerto Rican National Guard, two Pack Train companies, two mule drawn Wagon companies, one detached Service and Supply Company, one Signal and one Medical detachment. From all accounts, the new brigade commander and his executive officer did not find Gaillard a happy place. Factors of indiscipline were high while morale throughout the brigade was at its lowest ebb. Virginia Conner recalls that from the regimental commander down through the company commanders, Conner found a less than warm welcome. Life in this backwater post in a backwater department had taken its toll. Virginia states that on several occasions, Conner had to send Eisenhower to personally insure that even the simplest brigade directives were being carried out. The new brigade executive officer soon found himself in the undesirable position of reminding higher ranking regimental officers of what their duties and responsibilities were. Eisenhower subsequently became surreptitiously known as Conner's "hatchet man." Accounts of some 42nd Division staff officers are less than complimentary and disparage Conner's management style as unnecessarily demeaning and authoritarian while Eisenhower is described as a mere martinet. Consequently, neither the new commander nor his executive officer was popular within their new command, making their spouses' social interaction within the Gaillard community difficult at best. Living conditions in Panama for the young Mamie Eisenhower were spartan and uncomfortable. The heat and oppressive humidity of the long rainy season was as unwelcome as the unfamiliar animal and insect life that made daily life an unforgettable challenge. To the end of her long and widely traveled life Mamie Eisenhower regarded Panama as the worst place she had ever lived. Mamie vividly recalled to granddaughter-in-law, Julie Nixon Eisenhower, some fifty years later, her terror upon discovering a large bat in her Camp Gaillard quarters bedroom. Bats are not native to Panama, but rather a French import at unsuccessfully combating mosquito born illnesses. She recalled how her gallant husband came to her rescue by drawing his seldom-used ceremonial saber while leaping from bed to desk to chair attempting to run the hapless creature through. She also recalled the smell of having to put all four bedposts in coffee cans of fuel oil so that crawling insects could not reach the upper mattress. As the wife of a very unpopular officer, Mamie Eisenhower became socially isolated within the ever-shrinking confines of the small garrison. Such social isolation was contrary to her upbringing and previous, albeit limited, military wife experience. Social exclusion together with her husband's long hours at Brigade Headquarters caused Mamie to loath her time Panama. Virginia Conner saw the couple begin to drift apart as the young wife and her husband often quarreled. Virginia recounts that she offered Mamie counsel, comfort and advice and more often a shoulder to cry on, as both women were essentially in the same lonely social boat. Both couples eventually turned away from Gaillard and toward the more amenable society of dinners, balls and the excitement of the horse races in nearby Balboa and Amador. Conner's presence in the 20th Brigade operating area can be seen in some unlikely and unique reports. According to the records of the Federal Penitentiary in Atlanta, Georgia from 1921-1924, a sixty percent increase was experienced in the number of incarcerated soldier-prisoners from Forts Gaillard and Empire, Panama Canal Zone. This increase of military prisoners in the penitentiary convicted by general court-martial in Panama, of such offenses as larceny, indecent behavior with a minor, sodomy and gross insubordination serves as an indicator of the new brigade commander insisting on much tighter discipline and compliance with regulations by all members of his command.Just as much confusion exists regarding Conner's assignment to Panama and Camp Gaillard as does the biographical fog concerning Fox Conner himself. The location of Camp Gaillard was on the highest point along the Canal route, close to the Culebra, or Gaillard, Cut, the deepest and most difficult excavation ever attempted during the Canal's construction. Camp Gaillard, was located near the town of Culebra on what became the west bank of the canal. Initially it was known as Camp Elliott, a Marine barracks that provided security to workers during the canal construction period until 1919 when it fell under Army aegis. Legendary Marine turned pacifist Smedley Butler and leatherneck icon John Lejeune had been two of its commanders. To locate the camp, one must read Eisenhower's own description of how he arrived there. In At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends, Eisenhower tells how he and Mamie debarked from his transport ship, and unloaded their damaged and somewhat looted Model T Ford, probably at the military port of Cristobal, on the Caribbean side. Upon disembarkation the couple then caught the next Panama Canal Railroad train west. Eisenhower writes, " . . . we left the train to make our way to Gaillard. The first necessity was to walk hundreds of yards in the tropical heat across the Canal on one of the lock gates and then a walk through tall grass to Camp Galliard." Eisenhower paints the picture of the young soldier with his dutiful, yet somewhat reticent spouse at his side, suitcases in hand walking uphill through the saw grass toward the bleak post on the high banks of the Panama Canal. Considering the many places that he lived, it is most likely that at the end of a long life, Eisenhower's memory regarding Fort Galliard in At Ease was at best foggy on the details. Contrary to his memoir, to actually reach the Culebra Cut from the Pedro Miguel locks would not be a walk of hundreds of yards but rather a march of approximately nine miles during the oppressively humid tropical rainy season. It is more probable that a car from General Conner simply awaited the pair as they detrained at Pedro Miguel. Considering the many adventures in Dwight Eisenhower's long and phenomenal life, he can be forgiven remembering some minor details

A KANSAN IN PANAMA

Fox Conner in Panama, 1924 |

Pouring over historical maps, the pair re-fought the great campaigns of Alexander, Frederick the Great and often tried to out general Napoleon. It was Fox Conner, not West Point, who introduced Eisenhower to von Clausewitz. Conner was himself a student and tireless proponent of Clausewitzian thinking, though he was in the minority of Clausewitzian advocates among general officers at the time. As an instructor at the Command and General Staff School, Conner with a few others, had embraced the German military model rather than prevailing Jominian thought that so dominated American military thinking after 1871. It is evident in Conner's post-war lectures that he correctly interpreted Clausewitz regarding war as being more than simply an act of state policy to achieve a political aim. Conner taught Eisenhower to correctly decipher the rather ambiguous German term Politik, which means policy and politics, the sum total of a state's internal and external affairs as well as its strengths and weaknesses relative to its geo-political position. Eisenhower's understanding of Clausewitz and Politik became critical when early in his presidency he moved to unite his foreign policy and national security teams behind a singular approach before the Eisenhower Administration could move forward on Soviet policy and containment. The resultant "Project Solarium" was a testament to the application of Clausewitzian thought to security policy and the formation of the Basic National Security Policy (NSC 162/2). It is because of Conner's facility with Clausewitzian thought, his mentorship and incessant academic drilling, that Eisenhower read "On War" three times, a significant achievement in itself.

Conner's impact on Eisenhower, however, was not confined to just reading military theory and history. Conner required an intricate field order to be written for the operation of Ft. Gaillard on a daily basis. As a result, the reluctant football coach became so well acquainted with preparing detailed plans and issuing orders that they became second nature. Conner was often fond of quoting von Moltke and until the end of his life Eisenhower would use Conner's favorite von Moltke-ism, " planning is everything, plans are nothing." Conner's biographers claim that more than anything else, his persistent academic drilling insured Eisenhower's superlative standing at the Command and General Staff School in 1925. In reality, Conner trained Eisenhower to the curriculum at Fort Leavenworth using the "applicatory method," which referred to case studies of historical battles and campaigns. At the school, students advanced from military history lectures and original research to applying the lessons to battle situations using indoor sand table exercises. The students studied military scenarios and learned how to derive their own "estimate of the situation," using a systematic means of issuing orders in a standard template of five paragraphs incorporating their solutions. Such exercises were followed by tactical rides, field maneuvers with troops and staff rides studying actual battlefields. All agree it was in Panama that Eisenhower began establishing his reputation as an outstanding staff officer. Armed with this reputation, Eisenhower would be passed over the heads of more than hundred senior officers in line for general officer rank at the outbreak of the Second World War.

CONNER'S LASTING INFLUENCE: COALITION RATHER THAN COORDINATION

So convinced was Eisenhower by Conner of the inevitability of another European war that he ordered and persistently studied detailed maps of Europe, wrote complex and detailed war plans based on a multitude of European operational scenarios. Most importantly Eisenhower began to publicly champion the theory of unified allied command, the hypothesis that Conner and Pershing had championed many times at Chaumont. Conner counseled that when the United States entered the war it must never accept "coordination over unified coalition." Future war planners would have to overcome Foch's example of nationalistic considerations in the conduct of campaigns with multinational allies. Conner had made it clear in his personal instruction of Eisenhower at Galliard and later in his War College lectures that it would take both patient diplomatic skills and strong leadership to manage allies to victory. These tenets were to become the foundation upon which Eisenhower would build his entire SHAEF command philosophy.Although Eisenhower never served under Conner after Panama the General was never far away. It was by no less than by subterfuge that Eisenhower attended Command and General Staff School. He was turned down, by the Chief of Infantry, but within a week, Conner had Eisenhower transferred out of the Infantry and into the Adjutant Generals Corps where more slots for the school existed. Subsequently selected, the Command and General Staff School became the watershed of Eisenhower's career. He graduated first in his class in 1926. From there he secured assignments with Pershing, MacArthur, Krueger and ultimately Marshall. Retired in 1938, Conner, kept up a lively correspondence with his protégés during the war. During the war, General Pershing often delivered his views on how to win the war from the dining room of the Army Navy Club. However, Conner never offered advice but deferred to the men on active service and responded graciously to Patton, Marshall and Eisenhower's friendly letters. Major General Conner died in Washington, D.C., on October 13, 1951, after a prolonged illness and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. There is no evidence to show whether the first commander of the new North Atlantic Treaty Organization, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, was able to attend.

In 1967, former President Eisenhower noted in his memoirs, "He was the ablest man I ever knew. I can never adequately express my gratitude to this one gentleman. In a lifetime of association of great and good men, he is the one more or less invisible figure to whom I owe an incalculable debt." Collectively, Conner's biographers recognize the Eisenhower debt owed. Considering the company he kept as Supreme Allied Commander and as President of the United States this acknowledgment seems the ultimate accolade to the son of the blind Mississippi confederate soldier, one who, remains a biographical enigma to the present day.

About the Author and Sources

Russ Stayanoff is an instructor in US, European History and World Affairs at the Balboa Academy in Panama City, Panama. He received his BA in History from LaGrange College, LaGrange Georgia and an MA in Military History from Norwich University, Northfield, Vermont. He is a post-graduate student in Land Warfare at the American Military University in Manassas, Virginia. A veteran of the US Army, Stayanoff resides in the Republic of Panama. The photos came from from the Army Signal Corps collection, the Eisenhower Presidential Library and John Eisenhower's personal collection.

To find other Doughboy Features visit our |

Membership Information  Click on Icon |

For further information on the events of 1914-1918

visit the homepage of |

Michael E. Hanlon (medwardh@hotmail.com)