The Story of the American Expeditionary Forces

|

General Staff Insignia

|

THE MISSION

AND

BEGINNINGS

OF THE AEF

|

|

THE MISSION OF THE AEFBy Website Editor Michael E. Hanlon

While there were several sets of instructions issued to General Pershing and Admiral Sims, the Mission of the American Expeditionary Force was initially most concisely stated in the Declaration of War of April 6, 1917:

"...The President...is hereby authorized and directed to employ the entire naval and military forces of the United States and the resources of the Government: and to bring the conflict to a successful termination all the resources of the country are hereby pledged by the Congress of the United States."

Now this still leaves the issue as to what constituted a "successful termination" of the conflict. For America, the job of defining the terms of success fell solely to President Wilson. Over the first year of the US involvement, the aims and ideals he periodically outlined in his messages to Congress and public utterances evolved into the famous Fourteen Points.

Briefly summarized these required:

* Evacuation of occupied territories by the Central Powers;

* Adjustment of Italy's border and an independent Poland;

* Open international covenants, openly arrived at;

* Absolute Freedom of the Seas in War or Peace;

* Efforts to remove economic barriers; reduce armaments; and form a League of Nations;

* Impartial adjustment of colonial aims;

* Nationalities be given a chance for autonomous development;

|

Miss Liberty Backs the War Effort

|

In a practical sense, the Mission of the American Expeditionary Force was to help compel, through force of arms and in cooperation with its associates, Germany and the other Central Powers to accept these political terms.

And if this is an accurate delineation of the job that was to be done, it seems indisputable that the AEF successfully fulfilled its mission in the Great War, since Germany requested a cessation of hostilities based on the Fourteen Points. As historian David Trask put it:

| Rarely had a great nation followed a course so consistently and seemingly achieved its ends so fully. During 1918 the United States had gained its military goal - the provisional acceptance of President Wilson's plans for a post-war world. |

|

The attainment of these ends cost the Nation over 116,000 killed, 200,000 maimed and wounded and $36 Billion from the national treasury. Immediately after the war there was little doubt that the price had been worth paying. The disappointments over the punitive attitudes of the other victors at the Paris Peace Conference, the Senate's refusal to ratify the Versailles Treaty and the second thoughts about America ever becoming involved followed later. Such regrets, however, should not detract from recognizing the basic achievement by the AEF of its mission nor should it diminish in any way respect of Americans today for the sacrifices made by its members.

|

|

THE AEF IS FORMED

Despite President Wilson's proclamations of neutrality when the Great War began, the small United States military was forced to begin preparing for larger missions prior to the Declaration of War. Problems due to the unsettled political situation in Mexico provided one impetus. In 1914 there had been a showing of naval force and a landing of troops at Vera Cruz. Later, in response to raids into the United States by Pancho Villa, President Wilson [in March 1916] ordered Brigadier General John J. Pershing, Commander, 8th Brigade, 3rd Division, to take a punitive expedition into Mexico to assist the Mexican government in capturing Villa. For his mission Pershing organized a provisional division of two cavalry brigades of two cavalry regiments and two batteries of 3-inch field guns and one infantry brigade of two infantry regiments and two engineer companies with medical, signal, wagon, and air units as divisional troops. Although Pershing pursued Villa in vain throughout early 1916, he did fight two battles with Mexican government troops, who were also trying to catch Villa.

|

Early Image of a Doughboy

|

|

Because the Mexican government did not want the United States to do its work, it demanded the withdrawal of Pershing from Mexico. With the Mexican president threatening war unless the [American troops] got out of Mexico, and [with] Wilson unwilling to pull out Pershing, war seemed inevitable. As a result, the War Department called out the National Guard of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, but the Guard seemed hardly enough.

Meanwhile, forces from another direction were driving America towards a major expansion of its Army and Navy. In May 1915, the British liner Lusitania was sunk by a German submarine killing 128 Americans. This set off a diplomatic fire storm and triggered a political movement for military "preparedness". Americans started becoming aware that they could be dragged into the European war.

With the possibility of war with Mexico and with war already raging in Europe that could involve the United States, House and Senate conferees on Army legislation passed the National Defense Act of May 1916. Culminating two decades of political effort at modernizing the armed forces, the Act authorized doubling the Army and quadrupling the Organized Militia or National Guard over a period of five years, furnished a means of training new officers by establishing Reserve Officer's Training corps in colleges, and endorsed the Plattsburg summer camp programs

Click here to see Donald M. Kington's article The Plattsburg Movement and Its Legacy from the Relevance Archives.

The act permitted the Army to grow from 108,000 to 175,000 men during peacetime and expand to 285,000 men during war (65 infantry regiments, 23 cavalry regiments, 21 filed artillery regiments, 7 engineer regiments, 2 mounted engineer battalions, 263 coast artillery companies, and 8 aero squadrons) and form divisions and brigades. Soon these modest goals would seem almost ludicrous when it became time to send a multi-million man expeditionary force to Europe. But the implementation of the National Defense Act forced the Army General Staff to think hard about the requirements for dramatic expansion of the fighting force. This gave them a running start when war was declared in April 1917.

|

War Often Means Rationing

|

The American Expeditionary Force that went to France in 1917 and

1918 was a sketchily trained army built around a core of fewer than 130,000 prewar regular soldiers. [The recruitment goals authorized in the National Defense Act had not been met.] National guardsmen called to duty had a solid basis of military training, but the bulk of the AEF consisted of volunteers and draftees who had never been in uniform before.

|

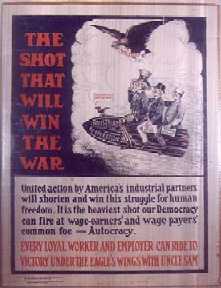

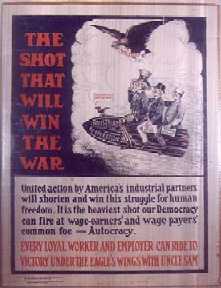

War Industries Workers Needed Encouragement, Too

|

Immediately after America entered the war, the problem of raising manpower was addressed at the urging of Army Chief of Staff Hugh Scott. Conscription would be needed. The President gave his assent and Army Provost Marshall Enoch Crowder drew up a bill that met with intense, but narrowly based opposition. On May 18th, Mr. Wilson signed the Selective Service Act which, after some expansion in 1918, would draft 2.7 million recruits to supplement the enlistments in the regular services and National Guard.

The United States Army was as inexperienced institutionally as its soldiers were individually. Many regulars and national guardsmen had recently served on the Mexican border and in the Punitive Expedition into Mexico, but those operations rarely involved maneuver of units larger than regiments; more often, they were independent troop and squadron patrols and raids. The Army's other combat experience was little more relevant. The Spanish-American War was brief, and although Corps headquarters were fielded, the conditions were undemanding by World War I standards. Neither did suppressing guerrilla warfare in the

Philippines or securing American interests in China offer many

useful lessons for senior commanders. Thus, as the Army went to

war, first hand knowledge about commanding and administering large

troop units was a scarce commodity. The Army had briefly

experimented with organizing and employing a division in the years

between the war with Spain and 1917, but the last significant

experience with corps and armies was in the Civil War. Thus when

General John J. Pershing took the AEF overseas, his senior

commanders really had as much to learn about the art of modern war

as did the soldiers.

The nine corps headquarters called for in the General Organization

Plan of the AEF were an essential part of Pershing's plan to build

and train an independent American Army in France. Such training was necessary not only to teach the soldiers the tactical lessons that the British and French had assimilated over four years of trench warfare, but also to train them in using weapons with which they had no experience. Among other things, the AEF had to learn about the employment of field and heavy artillery and aerial artillery observation techniques; gas warfare; the use of the tank and such weapons as trench mortars and heavy machine guns.

|

A Uniquely American Expression of the Martial Spirit |

|

Furthermore, corps commanders and staffs needed the opportunity to learn how to command divisions that numbered around 28,000 men each. By comparison, French and British divisions were about half as large, and German divisions roughly one-third the size of the American equivalent.

A total of 4,734,991 Americans would serve in the Armed Forces in the First World War. This would have supported an expeditionary force of 80 of these extra large divisions in Europe. However, with the help of the AEF, the war was brought to conclusion faster than anyone had dreamt possible in 1917. Only half the forces requested by General Pershing and the Army General Staff made it to France by the Armistice. Many doughboy's First World War service consisted of being drafted, reporting in, being partially trained stateside and then receiving their discharges. But the 2,000,000 men who made the trip to France proved the decisive military factor of the war.

The training of the American Expeditionary Force will be discussed in another feature article at the Doughboy Center.

|

|

Sources and thanks: Sources: The section on forming the AEF was patched together from two US Army official unit histories. Roughly, the first half of the section quotes directly from King of Battle: A Branch History of the U.S. Army's Field Artillery; by Boyd L. Dastrup, Field Artillery Branch Historian. The second half from V Corps in World War I, 1918-1919; by Dr. Charles E. Kirkpatrick, V Corps Historian. I contributed several sections of connecting material and the concluding paragraph. Professor Trask's comment was found in The United States in the Supreme War Council. The posters came from Mike Iavarone's TRENCHES ON THE WEB, the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian and the Hoover Institution. MH

|

To find other Doughboy Features visit our

Directory Page

|

For Great War Society

Membership Information

Click on Icon |

For further information on the events of 1914-1918

visit the homepage of

The Great War Society

|

Additions and comments on these pages may be directed to:

Michael E. Hanlon

(medwardh@hotmail.com) regarding content,

or toMike Iavarone (mikei01@execpc.com)

regarding form and function.

Original artwork & copy; © 1998-2000, The

Great War Society

|

|