EDITH CAVELL

Fragile Martyr

|

|

By Joy LaValley with Archival Material from Donna Cunningham

Both of the Great War Society

|

In the summer of 1914, Edith Cavell, head matron of the Berkendael Medical Institute, was on a brief holiday visiting her family in England when news came of the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in far Sarajevo. Edith's family urged her to stay in England, but she believed duty demanded that she return to the hospital in Brussels. When she said good-bye she did not know that she would never see her family again. On 4 August the Germans invaded Belgium. Soon the hospital where Edith worked became a Red Cross hospital and wounded soldiers from both sides Belgians, Germans, French, British were cared for.

There were posters all over Brussels warning that "Any male or female who hides an English or French soldier in his house shall be severely punished." In spite of this warning, there were soon successful efforts to hide soldiers who were wounded or separated from their units, then given refuge and helped to escape to safety. In Edith Cavell's hospital, wounded Allied soldiers were tended and then helped to escape. Soon Edith was persuaded to make room for some of the unfortunates who were not wounded but merely fleeing the Germans. They too were helped to get to places where they could rejoin Allied forces. The Germans became more watchful of the comings and goings at the hospital and Edith Cavell was warned by friends that she was suspected of hiding soldiers and helping them escape. But her strong feelings of compassion and patriotism overruled the warnings and she continued to do what she thought was her duty.

On 15 August 1915, as was almost inevitable, she was arrested by the German police and charged with assisting the enemy. The Germans suspected that not only were she and others helping Allied soldiers but that the same communication lines were used to divulge German military plans --- a serious charge indeed.

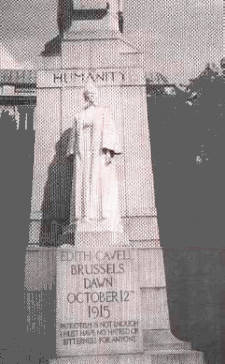

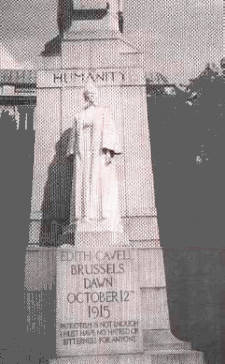

Trafalgar Square Memorial

|

Edith was held incommunicado for ten weeks. Brand Whitlock, the American minister to Belgium, was refused permission to see her. Even her appointed defense lawyer, Sadi Kirchen (a Brussels attorney), was not allowed to see her until 7 October, the day her trial began. Thirty-four others were accused of the same crime and were tried as a group. Several of the accused were friends of Edith's who had worked with her in helping the Allied soldiers.

The trial lasted only two days. Each person was accused of aiding the enemy and was told that, if found guilty, would be sentenced to death for treason. Edith's lawyer was eloquent in her defense, saying that she had acted out of compassion for others. But Edith's devotion to the truth condemned her she would not lie to save her life. She openly admitted that she had helped as many as 200 men to escape, who she knew they could then be able to fight the Germans again, and that some of them had written letters of thanks for her help. This was enough to cause her to be judged guilty and the sentence to be executed.

The final judgment was postponed for three days and during that time desperate attempts were made to save her. The American legation petitioned the German authorities in Brussels. A group composed of M. de Leval, the Belgian councilor to the American Legation; Hugh Gibson, secretary to the American Legation; and the Marquis de Villalobar, the Spanish minister to Belgium, made a hurried visit to the political governor of Brussels, Baron von der Lancken. He listened to their pleas but said that he could not reverse the court's decision. Only the military governor, Von Sauberzweig, had such authority. But even he, after being reached by phone, said that the sentence had to be carried out. In despair, the three men left they could do no more.

On 11 October the prison chaplain, the Rev. Gahan, visited Edith and found her resigned to her fate. She told him. "I want my friends to know that I willingly give my life for my country. I have no fear nor shirking. I have seen death so often that it is not strange or fearful to me." Even the German chaplain praised her for being "brave and bright to the last." On the morning of 12 October Edith Cavell and Philippe Baucq were taken to the Tir National, the Brussels firing range. At 7 a.m. both lay dead in the morning sun.

On the 90th anniversary of Edith Cavell's execution, a recently

completed cataloguing project of Prisoner of War files at The National

Archives in Kew has revealed the ineffectual efforts of government officials

to prevent the death of the British World War One hero.

The documents reveal the frustration, anger and eventual horror of the

Government's failure to save Ms Cavell, despite being notified of the

nurse's arrest and subsequent trial - on charges of aiding more than 200

allied troops to escape occupied Belgium - almost two months before her

execution on October 12 in Brussels.

Examples of documents within file FO 383/15 include the following

records.

24 August, 1915 (7 weeks before execution) "I have news through Dutch

sources that my wife's sister a Miss Edith Cavell has been arrested in

Brussels and I can get no news as to what has happened to her since August

5." - Personal Letter from Edith Cavell's brother-in-law, Dr Longworth

Wainwright informing the Foreign Office of her possible arrest.

21 September, 1915 (3 weeks before execution) "Ms Cavell has informed

the Legation that she has indeed admitted having hidden in her house English

and French soldiers. The legation will of course keep this case in view and

endeavour to see that a fair trial is given Miss Cavell." -

Inter-governmental correspondence from American Minister to Brussels, Brand

Whitlock, confirming Edith Cavell's arrest. (Received on September 28).

1 October, 1915 (2 weeks before execution) "I'm afraid it is likely to

go hard with Miss Cavell. I'm afraid we are powerless." - In-house memo from

Undersecretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Sir Horace Rowland.

9 October, 1915 (3 days before execution) "Dr Wainwright will be very

grateful for any further information that may be obtained and also for

instruction as to whether it is possible to communicate with or send

comforts to Miss Cavell." - Letter from Dr Wainwright. (Received October

11).

11 October, 1915 (1 day before execution) "(Miss Cavell's) trial has

been completed and the German prosecutor has asked for sentence of death

penalty against her. I have some hope that the court martial may decline to

pass the rigorous sentence proposed." - Inter-government correspondence from

Brand Whitlock.

That night, at 2am on the morning of October 12, 1915, Edith Cavell

was executed by firing squad, less than ten hours after sentence was passed.

Following Edith Cavell's execution letters, reports and newspaper

articles (found in FO383/15) give an insight into the horror being felt at

the events that took place. Included are the official report from the

American Legation in Brussels on the circumstances leading up to Edith

Cavell's death; and the harrowing blow-by-blow account of their desperate

efforts to save the nurse as the Germans rushed to execute her less than ten

hours after sentencing.

Examples of documents within file FO 383/15:

13 October, 1915 (Execution day plus 1)

"Miss Cavell sentenced yesterday and executed at two o'clock this

morning despite our best efforts continued until the last moment." -

Correspondence from US Ambassador to London, Walter Hines Page.

14 October, 1915 (Execution day plus 2)

"Dear sir, Forgive my worrying you again so soon, I had a wire dated

from Holland yesterday morning, 'Miss Edith Cavell died this morning' from

Gahan chaplain, Brussels. Have you any information on what this implies." -

Letter from Dr Wainwright.

"I had hoped that the Germans wouldn't go beyond imprisoning her in

Germany. Their action in this matter is part and parcel of their policy of

frightfulness and also I venture to think a sign of weakness." In-house memo

from Sir Horace Rowland.

15 October, 1915 (Execution day plus 3)

"The Foreign Office desire to state that in this country no woman

convicted of assisting the King's enemies, even found guilty of espionage,

has hitherto been subject to a greater penalty than a term of penal

servitude." - Foreign Office Press Release.

For further information visit: www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/catalogue

From Donna Cunningham

|

Even in death, Edith Cavell caused other lives to be saved. There was such a storm of protest all over the world that the Germans were moved to spare the lives of the other 33 accused prisoners. Another result of the tragic event was that thousands of volunteers in England, Canada, Australia and other parts of the British Empire lined up at recruiting stations. And in the United States, there was enormous popular pressure for America to declare war on Germany.

The name of Edith Cavell's lives on in many ways. In Brussels the nurses' training school is called Ecole Edith Cavell. In London's Trafalgar Square there is statue of her in her nurse's cloak. In Paris' Tuileries there is a beautiful sculpture of her. In Canada a western mountain is named Mt. Cavell. In the U.S. Rocky Mountains, there is Cavell Glacier. And in Swardeston, where she was born, the window over the altar of the church is dedicated to her. Edith is buried in Life's Green, close to the World War I memorial chapel at Norwich Cathedral. Her body was returned to England after the war ended and visitors still stop to see her grave.

.

Joy LaValley's article is a slightly abbreviated version of her piece which appeared in Relevance: The Quarterly Journal of the Great War Society, Vol. 5 no1. Donna Cunningham drew on Material made available on the 90th Anniversary of Nurse Cavell's execution. The photo of the Trafalgar Square Memorial was contributed by Lanayre Liggera, Chairman of the New York-New England Chapter of the Western Front Association.

|

|

For more Legends and Traditions of the

Great War return to the

Contents Page

|

For Great War Society

Membership Information

Click on Icon |

For further information on the events of 1914-1918

visit the homepage of

The Great War Society

|

Additions and comments on these pages may be directed to:

Michael E. Hanlon

(medwardh@hotmail.com) regarding content

Original artwork & copy; © 1998-2000, TGWS.

|

|

|