The Lafayette Escadrille

Over Verdun

|

|

|

An enduring legend of the Great War is of the contribution made by American aviators of the Lafayette Escadrille at the Battle of Verdun. Here is a firsthand account from one of the participants.

Sgt. James McConnell

With the American Escadrille at Verdun

Told by James R. McConnell, Sergeant-Pilot in the French Flying Corps

[In May 1916] The escadrille was ordered to the sector of Verdun. While in a way we were sorry to leave Luxeuil [in the Alsace], we naturally didn't regret the chance to take part in the aerial activity of the world's greatest battle. The night before our departure some German aircraft destroyed four of our tractors and killed six men with bombs, but even that caused little excitement compared with going to Verdun. We would get square with the Boches over Verdun; we thought it is impossible to chase airplanes at night, so the raiders made a safe getaway.

The fast-flowing stream of troops, and the distressing number of ambulances brought realization of the near presence of a gigantic battle. Within a twenty-mile radius of the Verdun front aviation camps abound. Our escadrille was listed on the schedule with the other fighting units, each of which has its specified

flying hours, rotating so there is always an escadrille de chasse over the lines. A field wireless to enable us to keep track of the movements of enemy planes became part of our equipment.

Lufberry joined us a few days after our arrival. He was followed by Johnson and

Balsley, who had been on the air guard over Paris. Hill and Rumsey came next, and after them Masson and Pavelka. Nieuports were supplied them from the nearest depot, and as soon as they had mounted their instruments and machine guns, they were on the job with the rest of us. Fifteen Americans are or have been members of the American Escadrille, but there have never been so many as that on duty at any one time.

Story of the Battles in the Skies

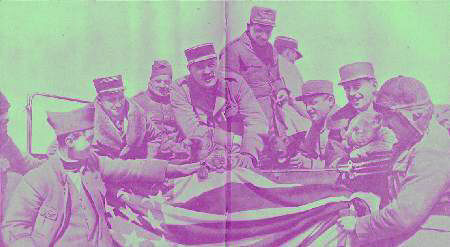

Escadrille Pilots with Their Mascots Including Whiskey the Lion

Before we were fairly settled at Bar-le-Duc, Hall brought down a German observation craft and Thaw a Fokker. Fights occurred on almost every sortie. The Germans seldom cross into our territory, unless on a bombarding jaunt, and thus practically all the fighting takes place on their side of the line. Thaw dropped his Fokker in the morning, and on the afternoon of the same day there was a big combat far behind the German trenches. Thaw was wounded in the arm, and an explosive bullet detonating on Rockwell's windshield tore several gashes in his face. Despite the blood, which was blinding him, Rockwell managed to reach an aviation field and land. Thaw, whose wound bled profusely, landed in a dazed condition just within our lines. He was too weak to walk, and French soldiers carried him to a field dressing-station, whence he was sent to Paris for

further treatment. Rockwell's wounds were less serious and he insisted on flying

again almost immediately.

A week or so later Chapman was wounded. Considering the number of fights he had been in and the courage with which he attacked it was a miracle he had not been hit before. He always fought against odds and far within the enemy's country. He flew more than any of us, never missing an opportunity to go up, and never coming down until his gasoline was giving out. His machine was a sieve of patched-up bullet holes. His nerve was almost superhuman and his devotion to the cause for which he fought sublime. The day he was wounded he attacked four machines. Swooping down from behind, one of them, a Fokker, riddled Chapman's plane. One bullet cut deep into his scalp, but Chapman, a master pilot, escaped from the trap, and fired several shots to show he was still safe. A stability control had been severed by a bullet. Chapman held the broken rod in one hand, managed his machine with the other, and succeeded in landing on a near-by aviation field. His wound was dressed, his machine repaired, and he immediately took the air in pursuit of some more enemies. He would take no rest, and with bandaged head continued to fly and fight.

The escadrille's next serious encounter with the foe took place a few days later. Rockwell, Balsley, Prince, and Captain Thenault were surrounded by a large number of Germans, who, circling about them, commenced firing at long range. Realizing their numerical inferiority, the Americans and their commander sought the safest way out by attacking the enemy machines nearest the French lines. Rockwell, Prince, and the captain broke through successfully, but Balsley found himself hemmed in. He attacked the German nearest him, only to receive an explosive bullet in his thigh. In trying to get away by a vertical dive his machine went into a corkscrew and swung over on its back. Extra cartridge rollers dislodged from their case hit his arms. He was tumbling straight toward the trenches, but by a supreme effort he regained control, righted the plane, and landed without disaster in a meadow just behind the firing line.

Soldiers carried him to the shelter of a near-by fort, and later he was taken to a field hospital, where he lingered for days between life and death. Ten fragments of the explosive bullet were removed from his stomach. He bore up bravely, and became the favorite of the wounded officers in whose ward he lay. When we flew over to see him they would say: il est un brave petit gars, I'aviateur américain. [He's a brave little fellow, the American aviator.] On a shelf by his bed, done up in a handkerchief, he kept the pieces of bullet taken out of him, and under them some sheets of paper on which he was trying to write to his mother, back in El Paso. Balsley was awarded the Medaille Militaire and the Croix de Guerre, but the honors scared him. He had seen them decorate officers in the ward before they died.

Story of Chapman's Last Fight

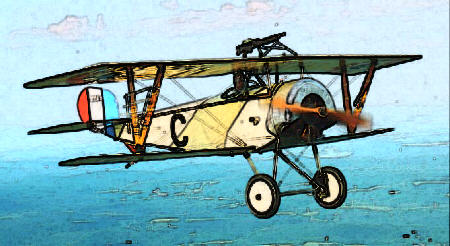

Replica of Victor Chapman's Nieuport 11

From the Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome

Then came Chapman's last fight. Before leaving, he had put two bags of oranges in his machine to take to Balsley, who liked to suck them to relieve his terrible thirst, after the day's flying was over. There was an aerial struggle against odds, far within the German lines, and Chapman, to divert their fire from his comrades, engaged several enemy airmen at once. He sent one tumbling to earth, and had forced the others off when two more swooped down upon him. Such a fight is a matter of seconds, and one cannot clearly see what passes. Lufberry and Prince, whom Chapman had defended so gallantly, regained the French lines. They told us of the combat, and we waited on the field for Chapman's return. He was always the last in, so we were not much worried.

Then a pilot from another fighting escadrille telephoned us, that he had seen a Nieuport falling. A little later the observer of a reconnaissance airplane called up and told us how he had witnessed Chapman's fall. The wings of the plane had buckled, and it had dropped like a stone he said.

We talked in lowered voices after that; we would read the pain in one another's eyes. If only it could have been some one else, was what we all thought, I suppose. To lose Victor was not an irreparable loss to us merely, but to France, and to the world as well. I kept thinking of him lying over there, and of the oranges he was taking to Balsley. As I left the field I caught sight of Victor's mechanic leaning against the end of our hangar. He was looking northward into the sky where his patron had vanished, and his face was very sad.

By this time Prince and Hall had been made adjutants, and we corporals transformed into sergeants. I frankly confess to a feeling of marked satisfaction at receiving that grade in the world's finest army. I was a far more important person, in my own estimation, than I had been as a second lieutenant in the militia at home. The next impressive event was the awarding of decorations. We had assisted at that ceremony for Cowdin at Luxeuil, but this time three of our messmates were to be honored for the Germans they had brought down. Rockwell and Hall received the Medaille Militaire and the Croix de Guerre, and Thaw, being a lieutenant, the Legion d'honneur and another "palm" for the ribbon of the Croix de Guerre he had won previously. Thaw, who came up from Paris specially for the presentation, still carried his arm in a sling. There were also decorations for Chapman, but poor Victor, who so often had been

cited in the Orders of the Day, was not on hand to receive them.

Story of the Morning Sortie over Verdun

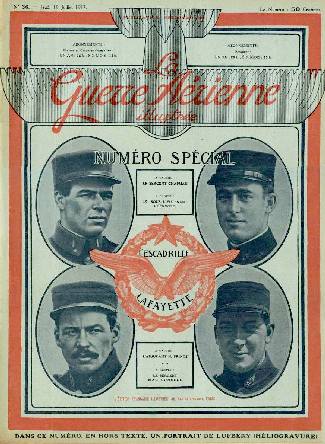

Contemporary Magazine Cover

Our daily routine goes on with little change. Whenever the weather permits - that is, when it isn't raining, and the clouds aren't too low - we fly over the Verdun battlefield at the hours dictated by General Headquarters. As a rule the most successful sorties are those in the early morning.

We are called while it's still dark Sleepily I try to reconcile the French orderly's muttered, C'est l'heure, monsieur, that rouses me from slumber, with the strictly American words and music of "When That Midnight Choo Choo Leaves for Alabam'" warbled by a particularly wide-awake pilot in the next room. A few minutes later, having swallowed some coffee, we motor to the field. The east is turning gray as the hangar curtains are drawn apart and our machines trundled out by the mechanics. All the pilots whose planes are in commission, save those remaining behind on guard - prepare to leave. We average from four to six on a sortie, unless too many flights have been ordered for that day, in which case only two or three go out at a time.

Now the east is pink, and overhead the sky has changed from gray to pale blue. It is light enough to fly. We don our fur-lined shoes and combinations, and adjust the leather flying hoods and goggles. A good deal of conversation occurs - perhaps because, once aloft, there's nobody to talk to.

"Eh, you," one pilot cries jokingly to another, "I hope some Boche just ruins you this morning, so I won't have to pay you the fifty francs you won from me last night!"

This financial reference concerns a poker game.

"You do, do you?" replies the other as he swings into his machine. "Well, I'd be glad to pass up the fifty to see you landed by the Boches. You'd make a fine sight walking down the street of some German town in those wooden shoes and pajama pants. Why don't you dress yourself? Don't you know an aviator's supposed to look chic?"

A sartorial eccentricity on the part of one of our colleagues is here referred to.

The raillery is silenced by a deafening roar as the motors are tested. Quiet is

briefly restored, only to be broken by a series of rapid explosions incidental to the trying out of machine guns. You loudly inquire at what altitude we are to meet above the field.

"Fifteen hundred meters - go ahead!" comes an answering yell.

"Essence et gaz! [Oil and gas!]" you call to your mechanic, adjusting your gasoline and air throttles while he grips the propeller.

"Contact!" he shrieks, and "Contact!" you reply. You snap on the switch, he spins the propeller, and the motor takes. Drawing forward out of line, you put on full power, race across the grass and take the air. The ground drops as the hood slants up before you and you seem to be going more and more slowly as you rise. At a great height you hardly realize you are moving. You glance at the clock to note the time of your departure, and at the oil gauge to see its throb. The altimeter registers 650 feet. You turn and look back at the field below and see others leaving.

In three minutes you are at about 4,000 feet. You have been making wide circles

over the field and watching the other machines. At 4,500 feet you throttle down and wait on that level for your companions to catch up. Soon the escadrille is bunched and off for the lines. You begin climbing again, gulping to clear your ears in the changing pressure. Surveying the other machines, you recognize the pilot of each by the marks on its side - or by the way he flies. The distinguishing marks of the Nieuports are various and sometimes amusing. Bert Hall, for instance, has Bert painted on the left side of his plane and the same word reversed (as if spelled backward with the left hand) on the right - so an aviator passing him on that side at great speed will be able to read the name

without difficulty, he says!

The country below has changed into a flat surface of varicolored figures. Woods

are irregular blocks of dark green, like daubs of ink spilled on a table; fields are geometrical designs of different shades of green and brown, forming in composite an ultra-cubist painting; roads are thin white lines, each with its distinctive windings and crossings - from which you determine your location. The higher you are the easier it is to read.

In about ten minutes you see the Meuse sparkling in the morning light, and on either side the long line of sausage-shaped observation balloons far below you. Red-roofed Verdun springs into view just beyond. There are spots in it where no red shows and you know what has happened there. In the green pasture land bordering the town, round flecks of brown indicate the shell holes. You cross the Meuse.

Immediately east and north of Verdun there lies a broad, brown band. From the Woevre plain it runs westward to the "S" bend in the Meuse, and on the left bank

of that famous stream continues on into the Argonne Forest. Peaceful fields and farms and villages adorned that landscape a few months ago - when there was no Battle of Verdun. Now there is only that sinister brown belt, a strip of murdered Nature. It seems to belong to another world. Every sign of humanity has been swept away. The woods and roads have vanished like chalk wiped from a blackboard; of the villages nothing remains but gray smears where stonewalls have tumbled together. The great forts of Douaumont and Vaux are outlined faintly, like the tracings of a finger in wet sand. One cannot distinguish any one shell crater, as one can on the pockmarked fields on either side. On

the brown band the indentations are so closely interlocked that they blend into

a confused mass of troubled earth. Of the trenches only broken, half-obliterated links are visible.

Columns of muddy smoke spurt up continually as high explosives tear deeper into

this ulcered area. During heavy bombardment and attacks I have seen shells falling like rain. The countless towers of smoke remind one of Gustave Doré's picture of the fiery tombs of the arch-heretics in Dante's "Hell." A smoky pall covers the sector under fire, rising so high that at a height of 1,000 feet one is enveloped in its mist-like fumes. Now and then monster projectiles, hurtling through the air close by, leave one's plane rocking violently in their wake. Airplanes have been cut in two by them.

For us the battle passes in silence, the noise of one's motor deadening all other sounds. In the green patches behind the brown belt myriads of tiny flashes tell where the guns are hidden; and those flashes, and the smoke of bursting shells, are all we see of the fighting. It is a weird combination of stillness and havoc, the Verdun conflict viewed from the sky.

Far below us, the observation and range-finding planes circle over the trenches

like gliding gulls. At a feeble altitude they follow the attacking infantrymen and flash back wireless reports of the engagement. Only through them can communication be maintained when, under the barrier fire, wires from the front lines are cut. Sometimes it falls to our lot to guard these machines from Germans eager to swoop down on their backs. Sailing about high above a busy flock of them makes one feel like an old mother hen protecting her chicks.

Getting started is the hardest part of an attack. Once you have begun diving you're all right. The pilot just ahead turns tail up like a trout dropping back to water, and swoops down in irregular curves and circles. You follow at an angle so steep your feet seem to be holding you back in your seat. Now the black Maltese crosses on the German's wings stand out clearly. You think of him as some sort of big bug. Then you hear the rapid tut-tut-tut of his machine gun. The man that dived ahead of you becomes mixed up with the topmost German. He is so close it looks as if he had hit the enemy machine. You hear the staccato barking of his mitrailleuse and see him pass from under the German's tail.

The rattle of the gun that is aimed at you leaves you undisturbed. Only when the

bullets pierce the wings a few feet off do you become uncomfortable. You see the gunner crouched down behind his weapon, but you aim at where the pilot ought to be - there are two men aboard the German craft - and press on the release hard. Your mitrailleuse hammers out a stream of bullets as you pass over and dive, nose down, to get out of range. Then, hopefully, you re-dress and look back at the foe. He ought to be dropping earthward at several miles a minute. As a matter of fact, however, he is sailing serenely on. They have an annoying habit of doing that, these Boches.

Story of a Fight over Fort Douaumont

Raoul Lufberry by His Spad

Rockwell, who attacked so often that he has lost all count, and who shoves his machine gun fairly in the faces of the Germans, used to swear their planes were armored. Lieutenant de Laage, whose list of combats is equally extensive, has brought down only one. Hall, with three machines to his credit, has had more luck. Lufberry, who evidently has evolved a secret formula, has dropped four, according to official statistics, since his arrival on the Verdun front. Four "palms" - the record for the escadrille, glitter upon the ribbon of the Croix de Guerre accompanying his Medaile Militaire.

A pilot seldom has the satisfaction of beholding the result of his bull's-eye bullet. Rarely - so difficult it is to follow the turnings and twistings of the dropping plane - does he see his fallen foe strike the ground. Lufberry's last direct hit was an exception, for he followed all that took place from a balcony seat. I myself was in the "nigger-heaven," so I know. We had set out on a sortie together just before noon, one August day, and for the first time on such an occasion had lost each other over the lines. Seeing no Germans, I passed my time hovering over the French observation machines. Lufberry found one, however, and promptly brought it down. Just then I chanced to make a southward turn, and caught sight of an airplane falling out of the sky into the German lines.

As it turned over, it showed its white belly for an instant, then seemed to straighten out, and planed downward in big zigzags. The pilot must have gripped his controls even in death, for his craft did not tumble as most do. It passed between my line of vision and a wood, into which it disappeared. Just as I was going down to find out where it landed, I saw it again skimming across a field, and heading straight for the brown band beneath me. It was outlined against the shell-racked earth like a tiny insect, until just northwest of Fort Douaumont it crashed down upon the battlefield. A sheet of flame and smoke shot up from the tangled wreckage. For a moment or two I watched it burn; then I went back to the observation machines.

I thought Lufberry would show up and point to where the German had fallen. He failed to appear, and I began to be afraid it was he whom I had seen come down, instead of an enemy. I spent a worried hour before my return homeward. After getting back I learned that Lufberry was quite safe, having hurried in after the fight to report the destruction of his adversary before somebody else claimed him, which is only too frequently the case. Observation posts, however, confirmed Lufberry's story, and he was of course very much delighted. Nevertheless, at luncheon, I heard him murmuring, half to himself: "Those

poor fellows."

The German machine gun operator, having probably escaped death in the air, must

have had a hideous descent. Lufberry told us he had seen the whole thing, spiraling down after the German. He said he thought the German pilot must be a novice, judging from his manoeuvers. It occurred to me that he might have been making his first flight over the lines, doubtless full of enthusiasm about his career. Perhaps, dreaming of the Iron Cross and his Gretchen, he took a chance - and then swift death and a grave in the shell-strewn soil of Douaumont.

. . . We American pilots, who are grouped into one escadrille, had been fighting above the battlefield of Verdun from the 20th of May until orders came the middle of September for us to leave our airplanes, for a unit that would replace us, and to report at Le Bourget, the great Paris aviation center.

Author James McConnell, in March 1917, was the last American aviator killed by the enemy before America's entry into the World War.

Additional information on the Lafayette Escadrille can be found at these websites:

Thanks to Tony Langley for finding this article and providing the images.

|

|

|

|

|

|