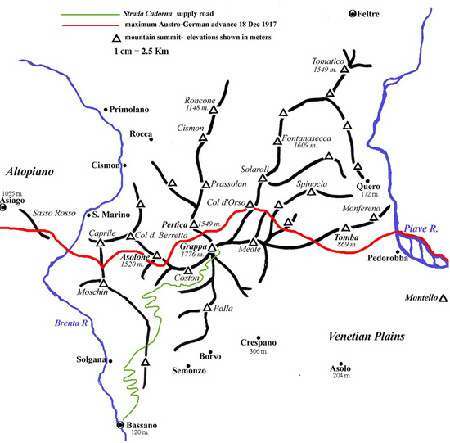

Monument at Bassano to "The Boys of 99"On the 8th of November 1917, Italian commander-in-chief Cadorna, as much a political creature as general, was replaced by General Armando Diaz, whose leadership included applying new tactics and a flexible strategy while ignoring the political intrigues in Rome. He better utilized artillery according to its range and replaced the once vulnerable [indeed solitary] Italian frontline with a system of multiple, interlocking trenches and defensive fires. Cadorna's leadership had featured over-control by an isolated, rigid command. Italian commanders at all levels wasted precious time waiting for direct permission to attack, then halting or retreating could result in summary execution for officers, sergeants and soldiers alike. In contrast, Diaz unified Italy's tactical doctrine, granted subordinate commanders needed flexibility and initiative, and improved dialogue with the Allies. Leaves were greatly increased, a morale building luxury almost unknown under Cadorna. New units of Italian shock troops, the Arditi or "bold ones," were also placed on line. Conceived in mid-1917, by a Captain Barri, their use was not fully understood by the high command. Now it was. Events elsewhere in Europe affected the situation in Italy. Most of the German units that had been so decisive at Caporetto [and so decimated on Grappa] were withdrawn for "Operation Michael," Field Marshall Ludendorff's first Spring Offensive of 1918. Its rapid success caused six of the British and French divisions in Italy to be withdrawn immediately to help counter this dire threat to the entire Western Front. Two Italian divisions and 60,000 Italian laborers were also sent to France--the infantry going to the frontline immediately, the laborers releasing a similar number of Frenchmen for combat duty. Over ten thousand of these Italian fanti that went to France would never return. They fell in the great summer offensives of 1918, including the Second Battle of the Marne; along side the French, British and now formidable American Army.  Map of Monte Grappa SectorOn the 15th of June 1918, Austria's final offensive began on three areas of the Italian Front- "Operation Avalanche" at Passo Tonale in the mighty northwestern Alps [actually a diversion], "Operation Radetzky" on the Asiago Altipiano and "Operation Albrecht," centering on the Grappa-Piave area. 100,000 Austrian gas shells, accompanied ten times as many high explosive rounds rained on the Grappa-Piave line in the opening barrage alone. Italy's troops were now equipped with the new "box-type respirator" gas masks, the same used by British and American forces. These masks withstood the gas barrage. Where the Italians caught hell was in their shallow trenches. The fate of Allied troops on the Western Front would befall their Latin brothers. British, French and Italian commanders believed that "deep trenches produced cowards." Austrians and Germans generals held opposite views; some Austrian dugouts had three meters of solid rock overhead. On the Asiago plateau, the Austrian attack focused on British and French forces, considering them the true threat, not "inferior" Italian troops elsewhere along the front line. Austrian success on these highlands would flank the Grappa/ Piave line. A breakthrough onto the lowlands would split the entire front and once again jeopardize Italy's survival. In the spring of 1916 the Italian Army had held the line on the Altipiano, invariably on the last ridge of mountains, holding out until the Russian Brusilov Offensive drew away Austria's attacking forces. In 1918 there would be no Russian threat, but what did occur was a repeat of 1916. The Austrians were once more halted on the very rim of the plateau. This time by an Allied conglomeration of the British 48th and French 23rd divisions, a new Italian sponsored Czech [nationalist] regiment and seven divisions of Bersaglieri, Alpini and regular infantry from across Italy. Although the key town of Asiago was destroyed and captured, the Italian counteroffensive dealt the 24 Austrian divisions a terrible defeat with over 30,000 casualties. The Allies suffered 8,000 killed, wounded and missing--75 percent being Italian.  Austrian Assault Troops, Spring 1918Young American Red Cross volunteer Ernest Hemingway also witnessed these battles on Monte Grappa and the Piave. Wounded while carrying rations to Italian troops, he wrote home of the battle's ferocity, plush hospitals and the ground being "black with dead Austrians." The Battle of the Solstice was "a great victory and showed the world what wonderful fighters the Italians are." The battle along the Piave River, the primary effort of the Austrian attack, was a disaster. Despite being outnumbered two to one, the Italian line held. Intercepted radio messages revealed the coming attack and Italian artillery pounded the Austro-Hungarian assembly areas. On the 17th of June 1918, a bridgehead across the Piave seven kilometers deep and twenty wide was lost as the river flooded due to heavy rains in the mountains. In this area alone, 24,000 Austrians were cut off from retreat and captured. The storms that had led to initial Austro-Hungarian success on Monte Grappa were concluding with catastrophe on the floodplains below. Italian and Canadian aircraft destroyed enemy pontoon bridges attempting a rescue. After hearing of Austria's Solstice disaster, the German foreign secretary told his government not to expect an end to the war by military means alone. The Germans had placed great faith in this offensive. Victory in the Alps might broker a better peace treaty with the Allies, an option being seriously considered in Berlin and Vienna. Austrian losses were close to 180,000 including over 35,000 atop Grappa. Italian casualties totaled nearly 85,000 with 14,000 on the mountain. The one French and two British divisions that participated on the Piave suffered over 3,000 killed, missing or wounded. The Allied commander Foch urged Diaz to exploit his victory with a counteroffensive. Diaz refused, replying an Italian counterattack would be as costly as the Austrians had just suffered. In late 1917 Italy had survived one of the greatest offensives of the war and now held the line during a second onslaught, both battles centering on the Grappa massif. The mighty peak would now witness Italy's greatest victory. Vittorio Veneto, the concluding battle of this front and war, began on Monte Grappa. The mountain phase of this Italian attack became a sacrificial diversion for the main Italian push on the upper Piave River, the offensive that would eliminate the armies of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In the early morning of the 24th of October 1918, exactly one year after the battle of Caporetto began, 1600 cannons, 500 trench mortars and nine Italian infantry divisions attacked into the clouds and Austrians trenches atop the Grappa massif. Within two days Austrian forces grew from nine divisions to fifteen, including the elite Edelweiss [mountain] Division. Again the battle was insane within the perpetual fog and storm. As positions shifted, artillery became for the most part useless. Trench warfare's terrible tactics would prevail atop this rock bound cluster of peaks and ridges. The Austrian command considered the attack at Grappa the key movement of the Italian Army. Indeed many of Italy's best units were in combat atop the peak: the King's Own Regiment, the highly decorated Aosta Brigade, an entire division of Alpini and several battalions of Arditi. The effects of Austrian counter-attacks on the Italians are described in Italian histories as "a heavy sacrifice of human life." The Aosta, Udine, Firenze and Abruzzi brigades suffered over fifty percent casualties, but held their new line on the peaks of Asolone, Pertica and Tomba.  Italian Trench, Monte GrappaWhat accelerated the collapse of the Austrian defenses occurred to the rear of the Piave line on the 28th of October. On the Grappa massif's eastern hills, regrouped Italian forces [assumed destroyed by both sides] broke out into the lowlands. This move transformed the battle into a complete Italian rout. It was not until this final week of the war that the Emperor's army fell apart, when Austrian troops could not rely on the Empire's "other" races. Along the entire front, the Empire's once loyal subjects of Czechs, Hungarians, Croatians and Poles now realized their people back home were setting up provisional or independent governments and laid down their arms, often motivated by Italian pleas via propaganda leaflets. Loyal Austrian units fearing entrapment began a full retreat. The battle soon turned into a pursuit. From Passo Tonale to the Adriatic similar events took place as the Piave line collapsed. It was now up to Italian cavalry units to cut off the retreating Austrian armies. The attack from Monte Grappa had succeeded at a high cost, especially to the Class of 1899. 24,000 Italians were killed, missing or wounded atop Monte Grappa, two thirds of Italy's losses in the war's final battle. Over 4,000 Anglo-French troops were casualties. One hundred thousand Austrian were killed, missing or wounded during the battle and retreat. Four hundred thousand Austrians were captured before their nation surrendered on November 4th, as well as massive amounts of arms and stores. As much as Verdun or Gallipoli, the attrition on Monte Grappa embodies the Great War. But this rarely mentioned battlefield has another quality that makes its story additionally dramatic. Imagine the Somme with a two thousand foot elevation gain for every mile. Or imagine Ypres having forty-degree rock slopes with trenches chiseled out of solid stone. Extreme effort and high casualties were always expected during First World War attacks. Imagine, however, advancing up mountain slopes, over barren rock, in dense cloud and howling wind or in a horizontal blizzard of sleet or snow. The incredible resiliency and tactical effectiveness of the Italian infantryman and his stalwart enemy, the troops of the crumbling Austro-Hungarian Empirestands out amongst the fighters of the Great War.  Italian Dead, Monte GrappaFor the Italian Class of 1899 [and 1900] there would be no divine intervention in their government's Abraham-like sacrifice at this modern Thermopylae. Across Italy there are statues to the men lost in la Grande Guerra, and il ragazzi del '99--the nation's tragic metaphor of the Great War. The "Boys of '99" would be Italy's contribution to this war's "Lost Generation." Nowhere is it more poignant than outside the town of Bassano, where a single bronze soldier implores the passersby to remember them and the peak so obvious behind him. Atop Monte Grappa is the frozen stone crypt of thousands of mountain warriors and a view that still defies description, of how critical the situation was for Italy in late 1917 and how fierce men are when faced with a nation's survival and the ends of the earth.  Monte Grappa TodayIn Italian, two books stand out- L'Invasione Del Grappa a cooperative effort by Heinz von Lichem, Alessandro Massignami, Marcello Maltauro and Enrico Acerbi. Its accounts of the battles in November and December of 1917 utilize oral history and diary as well as aerial photographs and maps to enhance each author's account of the battle. Carlo Meregalli's Grande Guerra-Tappe della Vittoria covers Italy's major battles in WW1 with map, photograph and precise descriptions. The statistical information is nothing short of amazing. For anyone studying the Italian Army's efforts in the war this book is a must. The three-volume history Gebirgskrieg by Heinz von Lichem is perhaps the essential study of World War One in the Alps. From the soaring northwestern frontier to the traumatic Isonzo Front, this book documents all aspects of the war. Although I am slow in German [and Italian] von Lichem's use of battle dispatches, oral histories, art and statistics are all worth the effort. The emphasis is Austro-Hungarian, but well done and complete. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||