| Back | Special | Library | Search | Home | Help |

The German Stahlhelm, M1916

|

Contributed by

Ralph Reiley (Reileys@worldnet.att.net)

The German Stahlhelm, M1916The failure of the Schlieffen plan in August of 1914, combined with the advances in the range and accuracy of firearms and the machine gun, lead to the stalemate the European powers found themselves inexorably mired in. The result was the terrible situation of trench warfare. Armies could not advance in the face of the overwhelming firepower of their opponents. The end result was that both sides dug in from the North Sea in Belgium to the Swiss border. The resulting siege warfare was not envisioned by anyone. The weapons used by the infantry were designed to engage the enemy at ranges greater than 1000 meters. Trench warfare changed all plans. Weapons designed for long range use, were used in close quarters. At the Battle of Mons, the casualty rate of the tightly packed ranks of German soldiers attacking the British were enormous. It was discovered later that one rifle bullet would pass through two, sometimes three soldiers, when fired at ranges of less than 1000 meters. Trench warfare lead to the re-discovery of many once obsolete military items. The improvements in the accuracy and range of firearms during the 18th Century, as well as the development of improved battlefield tactics, rendered many traditional military items obsolete, such as the steel helmet, body armor, and the hand grenade. The extended siege nature of trench warfare during the First World War found these once obsolete items re-introduced into the military inventory.

One of the many horrors of trench warfare was the large numbers of head wounds among soldiers of all the armies on the Western Front. Standing in a trench, the head is the most exposed portion of the body, making a wound from a sniper's bullet, artillery shell fragment, or a shrapnel ball more likely. In 1914, the term shrapnel referred to a specific type of artillery shell. It detonated in the air, and was full of lead or steel balls, a 20th Century version of 18th and 19th Century grapeshot. The other main artillery shell type of 1914, was the high explosive shell, which broke up into many fragments upon detonation. In the terminology used today, shell fragments are referred to as shrapnel. The Germans were the first to start testing a steel helmet, but the last to introduce it on the battlefield. The French were first to issue a steel helmet to the front line troops. In March of 1915 a steel skull cap was issued, to be worn under the wool Kèpe. By the end of the year the skull cap had been replaced by more than 3 million M1915 Adrian pattern steel helmets. The French helmet was made from mild steel, and was based on the French Fireman's helmet of the time. The Italians, Russians, Belgians, and Serbians adopted the Adrian Helmet for their armed forces. The British soon followed with the Brodie shrapnel helmet, and was named after the inventor. It was derived from a helmet popular during middle ages, and very economical to produce. It was made from manganese steel, and was designed to provide protection from air-burst shrapnel and shell fragments. By July of 1916, 1 million had been delivered to the Western Front. The British used this helmet untill the 1980's, and the United States also used the Brodie helmet from 1917 to 1942. The M1916 Stahlhelm The German Pickelhaube (spiked helmet) was found to be totally unsuitable for trench warfare. It was not durable in the rough conditions of the trenches, it was very expensive to produce, and it provided no real combat protection. In 1915, Army Group Gaede, named after the commanding general, was in position in the Vosges Mountains, near the Swiss border. General Gaede was alarmed about the high number of head wounds his soldiers were receiving, in his relatively 'quiet' sector of the front. Growing frustrated with administrative red tape and lack of action, he had his own helmet designed, and supplied about 1,500 to his front line troops. Few examples remain, as most were melted down after the M1916 Stahlhelm was introduced. Gaede's helmet was very heavy at 4 1/2 pounds. It consisted of two parts, a soft leather and cloth skull cap that covered the head and a heavy steel plate, attached to the leather cap with rivets. The thick curved steel plate only covered the forehead area, with a long nose piece hanging down, similar to the Norman helmets of the 11th Century. It only protected the front of the head, where the majority of wounds occurred. The helmet was less than successful, but it did have one feature that was later used in the stahlhelm. It was made from a chromium-nickel steel alloy, that proved to be very strong.

After extensive testing for the optimum shape, the distinctive "Coal Scuttle" design was determined to be the best shape for protecting the head and neck. This design had its roots in a helmet popular in the 16th Century. In February of 1916, the stahlhelm was introduced in small numbers to the front line troops engaged in the battle of Verdun. The resulting reduction in the number of head wounds suffered by the soldiers lead to mass production of the M1916 stahlhelm, and the replacement of the pickelhaube within a few months on the Western Front, and on the Eastern Front by mid-1917. When the new helmet was first introduced, the troops leaving the trenches turned their helmets over to the troops relieving them. It is not uncommon to see photographs from this period of soldiers in the same unit wearing both the pickelhaube and stahlhelm, as supply could not meet demand for some time.

The basic helmet shell is formed from one steel disk, and went through at least nine stamping stages before it reached its final shape. The rivets at the lower side skirts fasten M1891 pickelhaube side posts, to attach M1891 pickelhaube chinstrap. The helmet liner is held in place with 3 split rivets. The liner was made of a leather or sheet metal band with three leather tabs with pads attached to it, which formed a very efficient internal sizing system. The liner was designed so that the helmet would remain 1 finger width away from the head at the sides, and two at the top. This was to prevent injuries to the head by objects striking the helmet and denting it. At the sides of the helmet are two large lugs, which served two functions. The first function was for ventilation of the helmet; and second function was to support a heavy armored plate, called a Stirnpanzer. The plate was notched so that it could hang on the lugs, and was secured with a leather strap that fastened at the back of the helmet. Issued along with this armored helmet plate, was a set of sectional chest armor, called lobster armor by collectors, which weighed 35 pounds. It was thought that this armor would protect sentries and machine gunners who were more exposed to enemy fire than other troops. Generally the soldiers threw the armor away at the first opportunity, as wearing the cumbersome armor in the trenches was of dubious value, making both the helmet plate and lobster armor quite rare today.

The stahlhelm came in several sizes, as did the pickelhaube. The smallest size was 60, and the largest was 68, although some size 70 were made. The smaller sized helmets, size 60, 62 and 64, had an extra step on the helmet lugs, to make up for their small size so that the helmet plate, which only came in one size, could be attached to all helmets. The size of the helmet is usually stamped somewhere on the inside skirt.

In late 1916, a white helmet cover was tested for winter camouflage. It was not particularly successful. In February of 1917, a grey canvas helmet cover began to be issued to cut down glare on the helmet from the sun and moon. In 1917, the helmet was simplified by removing the pickelhaube chinstrap mounts, and attaching the chinstrap directly to the helmet liner. This helmet was designated the M1917 stahlhelm. In early 1918, another variation was tested. Collectors refer to it as the telephone-operator helmet, or cavalry model, as it had a curved section removed from the side skirts, to uncover the ears. The M1918 stahlhelm design was intended to reduce blast injuries to the ears caused by the deep skirt. This modification did not seem particularly successful, and this M1918 helmet was not produced in large numbers.

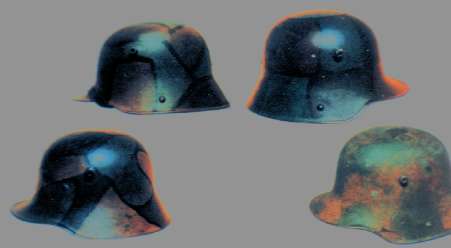

The stahlhelm was painted field grey, until an order of the General Staff, dated July 7, 1918, ordered a camouflage paint scheme. The official camouflage pattern for new helmets was painted over a green or brown base coat. A colored lozenge pattern was used, with a black finger wide stripe separating the green, yellow ocher and rust brown camouflage colors. Helmets already in the field were to be painted in camouflage colors as well as local conditions allowed. Camouflage helmets also exist where the various colors are blended together, without the black striping. Camouflage helmets, despite the official order for all helmets to be repainted, are not common, and draw a higher price with collectors than standard field grey helmets.

The German M1916 stahlhelm remained basically unchanged until it was replaced by the M1935 stahlhelm. The armor plate support lugs were removed, the skirts were reduced in size, and the thickness of the steel was reduced, producing a much lighter helmet. It is interesting that the kevlar helmet used now by the U.S. Army bears a striking resemblance to a helmet designed over 80 years ago. For more detailed information on German helmets, refer to the book list below. For Further Reading

© 1997 Ralph Reiley - All rights reserved |