June |

Access |

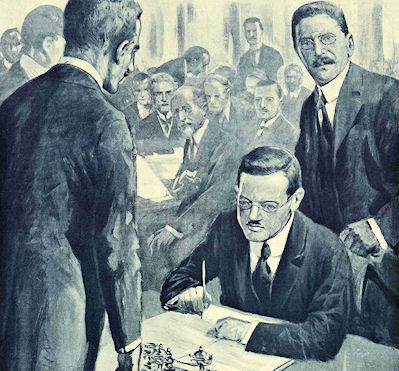

At the Hall of Mirrors 100 Years Ago

Signing the Treaty of Versailles

|

||||||||

|

In the late summer of 2017, at the request of the United States World War One Centennial Commission, I asked our readers to propose appropriated inscriptions for the National WWI Memorial planned for Pershing Square in Washington, DC. Your response was great and subsequently I forwarded nearly 100 of your suggestions to the commission's Vice-Chairman, Edwin Fountain. Recently, Mr. Fountain shared the final selections with me and asked me to pass these on to you. While none of our proposals made the final list, he expressed great appreciation and thanks for our efforts.

The final group of five includes quotes from President Wilson, General Pershing, poet and AEF veteran Archibald MacLeish, author Willa Cather, and Nurse Alto May Andrews. The complete official listing is presented on our blog Roads to the Great War, including information on the contributors and their connections to the war, and the original source and context of the material. Just click on the image just above on the left to access the full article. MH

America's Siberian Intervention: Part 3 of 4,

Winter Comes

Doughboys on the March in Siberia

The Americans faced a dismal winter. Temperatures frequently dropped to below 60 degrees. below zero. Frostbite was common and in some cases led to amputation. The Chief Surgeon noted that "practically" no sanitary conditions existed. Drinking at the popular vodka houses and engaging prostitutes became the most popular pastimes for many bored and lonely Doughboys needing an escape from the harsh conditions.

By spring 1919, the 27th Infantry found themselves divided between the Trans-Baikal region and Habarovsk on the Amur River; while detachments of the 31st Infantry were distributed along the railroad from Vladivostok to the Suchan Valley. In March, the need to transport military supplies and maintain communications for the White Russians produced the Inter-Allied Railway Agreement which divided the 6,000-mile-long Trans-Siberian Railway into sectors. Allied military detachments would protect their sectors from guerilla attacks and keep the railway and lines of communication open. Graves immediately issued orders to his troops: "Our aim is to be of real assistance to all Russians in protecting necessary traffic movements within the sectors on the railroad assigned to us. . . All will be equally benefited, and all will be treated alike by our forces..." However, the railway was the main artery of White Russian forces and American detachments soon discovered that Russians along the Trans-Siberian Railway sympathized with the Bolsheviks.

At the village of Sviyangino, Bolshevik Partisans frequently wreaked havoc with the tracks and telegraph poles. As one soldier noted, "Almost daily we had been called to repair destroyed stretches [of track]." At Novitskaya, a partisan ambush led to the deaths of five American soldiers. Partisan duplicity disturbed most Americans. Locals who sold them milk and vegetables in the morning often tried to kill them at night. But Cossack guerilla bands also plagued American detachments along the railroad. Cossack warlords such as Semenoff and Kalmikoff were pathological murderers who tortured, raped, and decapitated innocent Siberians. Nick Hochee of the 27th Infantry later recalled Kalmikoff: "His cutthroat Cossack Army was one of the most ruthless, cruel, inhuman animals of that time." Graves and American officers constantly received pleas from local Russians for protection against the Cossacks.

31st Infantry Field Kitchen in Siberia

American soldiers were also the targets of Cossack terror. Colonel Styer informed Graves in February 1919: "[Kalmikoff's] power of life and death has been so indiscriminately used as to create a reign of terror, and the life of no soldier or civilian is safe." At Posolskaya, Cossacks commanded by Semenoff opened fire with machine guns from their armored train into a boxcar of sleeping Doughboys. At Habarovsk, Kalmikoff's men killed an American signal corpsman working on a telegraph pole.

The Japanese financed many Cossack guerillas and condoned similar violence against the Russian people. Outnumbering Americans 10 to 1, they masked terror as anti-Bolshevism. The last thing many innocent people witnessed was the blade of a Japanese sword toward their throat. Bitter relations between American and Japanese officers came to a head in March 1919 when Graves refused to participate in their counterattack against a group of partisans who had killed 247 Japanese soldiers. Graves replied that the Japanese probably deserved it.

Graves had other difficult matters to attend. A miners' strike instigated by the Red Army in the Suchan Valley immobilized coal production needed by the railroad. The American detachment sent to the Suchan Mines had to restore stability without interfering between the Bolshevik miners and anti-Bolshevik administration. Graves's refusal to arrest striking miners infuriated anti-Bolsheviks who accused him of harboring Red sympathies.

On 23 May 1919, Bolshevik leader Yakov Triapitsyn, who had assisted striking miners, threatened to murder every American soldier in the Suchan Valley unless they withdrew from the area. Graves ordered that all partisans be removed by force. In August, Captain B. H. Roads with a 40-man detachment did just that. Triapitsyn retreated from the valley, and the mines operated quietly from then on.

Major General Graves (USA) and General Otani (Japan) with Their Staffs

Patrolling a sector near Romanovka, American soldiers from the 31st Infantry, now nicknamed the Polar Bears, faced certain death. At 4 a.m. on 25 June 1919 partisans opened fire into their camp. Using single shot rifles, the partisans took advantage of the unguarded camp left vulnerable between sentries and surrounded it. According to Sergeant Joseph B. Longuevan, bullets piercing their tents causing "some of the cots to topple" and one soldier "[was] hit 17 times." In the panic, few soldiers grabbed rifles or ammo as they headed for cover in nearby log houses.

Outnumbered 20 to 1, they faced imminent slaughter. Running low on ammo and seeing no reprieve, Corporal Brodnicki volunteered to go for help. Although seriously wounded, he found another American company. Four hours after the first gunshots, machine gun fire from Lieutenant Lorimer's platoon on the enemy's flank caused the partisans to withdraw. American casualties were heavy: 26 men died in the first minutes alone. Among the dead partisans, soldiers recognized a local man who regularly sold them milk.

In Iman, just north of Vladivostok, Kalmikoff's men kidnapped an American captain and corporal. The captain managed to escape, but the corporal remained. Major Charles A. Shamotulski arrived at Iman with 150 men from rifle and machine gun detachments for a showdown with the Cossacks. While the Japanese threatened to side with the Cossacks in an attack, Shamotulski stood his ground and they backed off. Brutally beaten and tortured by his captors, the corporal was released days later. Graves suspected the Japanese had orchestrated the whole thing.

Next Month in Part 4: Time to Head Home

Sources: Guarding the Railroad, Taming the Cossacks, U.S. National Archives; "AEF Siberia," The Doughboy Center

Versailles and Its Four Sisters

Polish Representative Ignace Jan Paderewski

at the Signing of the Treaty of Saint-Germain

Versailles was the first of five "Parisian" treaties: Saint-Germain with Austria, Neuilly with Bulgaria, Trianon with Hungary, and Sèvres with the Ottoman Empire, which quickly collapsed to be replaced in 1923 by the Treaty of Lausanne with Turkey. Ironically, the peacemaking took longer than the war itself.

![]() Conventions and Treaties of World War I

Conventions and Treaties of World War I

![]() Summary of the Terms of the Five Treaties (PDF)

Summary of the Terms of the Five Treaties (PDF)

![]() Treat of Saint-Germain

Treat of Saint-Germain

![]() Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine

Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine

![]() Treaty of Trianon

Treaty of Trianon

![]() The Treaty of Sèvres and Today's Middle East

The Treaty of Sèvres and Today's Middle East

![]() The Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne

![]() The Failure of the WWI Peace Treaties

The Failure of the WWI Peace Treaties

Memorable Dialog from WWI Movies

Tjaden: Well, how do they start a war? From All Quiet on the Western Front

Capt. von Rauffenstein: A 'Maréchal' and 'Rosenthal,' officers? From La Grande Illusion

Alvin York: Well I'm as much agin' killin' as ever, sir. But it was this way, Colonel. When I started out, I felt just like you said, but when I hear them machine guns a-goin', and all them fellas are droppin' around me... I figured them guns was killin' hundreds, maybe thousands, and there weren't nothin' anybody could do, but to stop them guns. And that's what I done.

From Sergeant York

Yevgraf Zhivago: In bourgeois terms it was a war between the Allies and Germany. In Bolshevik terms it was a war between the Allied and German upper classes - and which of them won was a matter of indifference. . . They [the warring powers] were shouting for victory all over Europe—praying for victory to the same God. My task—the Party's task—was to organize defeat. From defeat would spring the Revolution...and the Revolution would be victory for us.

From Doctor Zhivago

Von Klugermann: Well, aren't you coming [to the enemy pilot's funeral]? It's an order. From The Blue Max

Prince Feisal: The English have a great hunger for desolate places. I fear they hunger for Arabia.. From Lawrence of Arabia

Soldier #1: Well, one country offends another.

Tjaden: How could one country offend another? You mean there's a mountain over in Germany gets mad at a field over in France?

Soldier #1: Well, stupid. One people offends another.

Tjaden: Oh, that's it. I shouldn't be here at all. I don't feel offended.

Capt. de Boeldieu: They're fine soldiers..

Capt. von Rauffenstein: Charming legacy of the French Revolution

Capt. de Boeldieu: Neither you nor I can stop the march of time..

Capt. von Rauffenstein: Boldieu, I don't know who will win this war, but whatever the outcome, it will mean the end of the Rauffensteins and the Boeldieus.

Capt. de Boeldieu: We're no longer needed.

Capt. von Rauffenstein: Isn't that a pity?

Capt. de Boeldieu: Perhaps.

Stachel: Why?

Von Klugermann: Because our commanding officer has made it one. He believes in chivalry, Stachel..

Stachel: Chivalry? To kill a man, then make a ritual out of saluting him – that's hypocrisy. They kill me, I don't want anyone to salute

Von Klugermann: They probably won't..

Lawrence: Then you must deny it to them.

Prince Feisal: You are an Englishman. Are you not loyal to England?.

Lawrence: To England and to other things.

Prince Feisal: To England and Arabia both? And is that possible? I think you are another of these desert-loving English.

Despite my retirement from the business, there will still be possibilities for you to visit the battlefields of the Great War.

AEF Battlefields

Gallipoli

2019

From: Valor Tours, Ltd. / Mike Grams, Tour Leader

When: September 2019

Details: Request brochure via Email

HERE.

From: National World War I Museum / Clive Harris & Mike Sheil, Tour Leaders

When: October 2019

Details: Itinerary and Tour FAQ

HERE.

The Tiger in America

In 1865, fleeing from the wrath of Napoleon III's anti-radical agents, Georges Clemenceau came to the United States where he would work as a journalist and teacher for almost six years. He appreciated the freedom of expression he found in his sanctuary and kept politically active in French expatriate circles. Arriving in the immediate aftermath of the nation's Civil War, he also proved an ardent supporter of emancipation and an advocate for the harshest reconstruction policies. Before departing for home in 1870, he married an American, his former pupil Mary Plummer. Though Clemenceau collected mistresses, when his wife took a tutor of their children as her lover, he insisted on a separation, and they eventually had an acrimonious divorce. He made a brief triumphant return visit to the land of his exile, in 1922.

Say feller tell me how I can get back to my outfit?

One of the bitterest, yet moving and memorable, pieces of post-WWI literature is John Dos Passos's "The Body of an American," the concluding chapter of 1919, part two of his USA Trilogy. Here is an excerpt describing the initial selection:

In the tarpaper morgue at Chalons-sur-Marne in the reek of chloride of lime and the dead, they picked out the pine box that held all that was left of

enie menie minie moe plenty of other pine boxes stacked up there containing what they’d scraped up of Richard Roe

and other person or persons unknown. Only one can go. How did they pick John Doe? . . .

how can you tell a guy’s a hundredpercent when all you’ve got’s a gunnysack full of bones, bronze buttons stamped with the screaming eagle and a pair of roll puttees?

. . . and the gagging chloride and the puky dirtstench of the yearold dead . . .

Read the entire chapter HERE;

Visit Our Daily Blog

Looking Back: A Retrospective of the War

Part VI

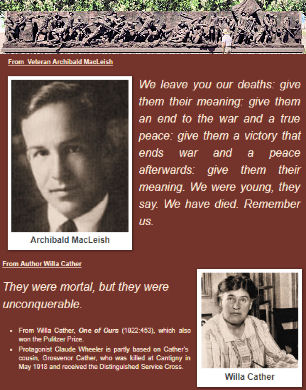

This is our sixth historic banner provided by the San Francisco War Memorial's World War I Armistice Centennial Commemorative Committee. Visit HERE to learn more about the commemorative exhibition being held in the City by the Bay.

La journée de Versailles

Der Tag von Versailles

The day of Versailles – June 28, 1919

By Charles B. Burdick

The Crowd Outside the Palace Grounds at Versailles

About 2:30 p.m. Georges Clemenceau entered the Hall of Mirrors

and looked about him to see that all arrangements were

in perfect order. He observed a group of wounded

veterans at one side with their medals of valor pinned to

their uniforms and, walking up to them, engaged them

in a brief conversation. At 2:45 p.m. he moved up to the

middle table and took his seat as the presiding officer.

Observant spectators noted the singular fact that he sat

almost directly under the ceiling decoration bearing the

legend, "The king governs alone." The spot was as close

as possible to the location of William I of Prussia when

he had become the German Emperor in 1871.

Wilson and Lloyd George entered the room soon after

Clemenceau, and the assemblage saluted them with

discreet applause. At last the table was full, except for

the German and Chinese delegations. Clemenceau

glanced to the right and to the left; people had taken

their seats but still conversed with their neighbors. He

made a sign to the ushers who whispered, "Ssh! Ssh!" to

the offenders. The talking ceased and only the sound of

occasional coughing and the dry rustle of programs

marred the silence. A sharp military order startled the

audience as the Gardes Republicaine at the doorway

flashed their sabers into their scabbards with a loud

click. In the ensuing silence Clemenceau, his voice

distant but penetrating, commanded, "Let the Germans

enter." His direction was followed by a hush as the two

German delegates, preceded by four Allied officers,

entered by way of the Hall of Peace and moved to their

seats. Dr. Mueller, a tall man with a scrubby little

mustache, wearing black, with a short black tie over his

white shirt front, appeared pale and nervous. Dr. Bell

held himself calm and erect. The Germans bowed stiffly

and sat down. The final moment had arrived at last.

Wilson made the audible remark, "How I hate them."

At 3:15 p.m. Georges Clemenceau rose and announced, "The

meeting is opened." He then spoke briefly in French:

An agreement has been reached upon the conditions of the

treaty of peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and

the German Empire. The text has been verified; the president

of the conference has certified in writing that the text about to

be signed conformed to the text of the 200 copies which have

been sent to the German delegates. The signatures about to be

given constitute an irrevocable engagement to carry out

loyally and faithfully in their entirety all the conditions that

have been decided upon. I, therefore, have the honor of asking

the German plenipotentiaries to affix their signatures to the

treaty before me.

The Germans rose quickly from their seats when he had

finished his remarks, knowing that they were the first to

sign, but William Martin, director of protocol, motioned

them to sit down. Mantoux, the official interpreter,

began translating Clemenceau's words into German. In

his first sentence, when he reached the words, "the

German Empire," or, as Clemenceau had said in French,

"l'empire allemande," he retranslated it as, "the German

Republic." While this change reflected political realities,

Clemenceau whispered, "Say 'German Reich,'" this

being the term employed by the Germans.

German Plenipotentiaries Hermann Mueller

and

Johannes Bell Signing the Treaty

Paul Dutasta, general secretary of the conference, then

led the five Germans–two plenipotentiaries and three

secretaries–to the treaty table where Mueller and Bell,

two lonely men in simple black frock coats among the

sea of colorful military and diplomatic uniforms, signed

their names. Bell's pen did not work and one of Colonel

Edward House's secretaries offered his personal pen for

the German's use. Mueller appended his name in the

cramped manner of a man trying to hide his

involvement in a dubious action while Bell, using the

loaned instrument, scrawled his nervous approval in

huge letters.

The delegation from the United States followed the

Germans. President Wilson rose, and as he began his

walk to the historic table, followed in order by Secretary

of State Robert Lansing, Colonel House, General Tasker

Bliss, and Henry White, other delegates stretched out

their hands in congratulation. He came forward with a

broad smile and signed his name at the spot indicated

by William Marten. Lloyd George, together with Arthur

Balfour, Viscount Milner, and Andrew Bonar Law,

followed the Americans. Then came the delegates from

the British dominions, followed by the representatives

of France, in order, Clemenceau, Stephen Pichon, Louis

Klotz, André Tardieu, and Jules Cambon; the president

of the council signed his name without seating himself.

The general tension that had prevailed before the

Germans had signed was now gone. There was a

general relaxation; conversation hummed again in an

undertone. The remaining delegations, headed by those

of Italy, Japan, and Belgium, stood up one by one and

passed onward to the queue waiting by the signing

table. Meanwhile, adventuresome onlookers

congregated around the main table getting autographs.

Everything went quickly. The efficient officials of the

Quai d'Orsay stood attentively in position indicating

places to sign, enforcing procedures, blotting with neat

little pads.

French 75s Preparing to Fire the Celebratory Barrage

Suddenly, as Ignace Jan Paderewski, the Polish

plenipotentiary, was signing his name, from outside

came the crash of guns thundering a salute, announcing

to Paris that the Germans had signed the peace treaty.

Through the few open windows came the sound of

distant crowds cheering hoarsely.

At 3:50 p.m. the signing process was complete. The

protocol officials renewed their "Ssh! Ssh!" injunction,

cutting short the loud, invasive chatter. There was a

final hush. Clemenceau announced, "Gentlemen, all of

the signatures have been given. The signing of the peace

conditions between the Allied and Associated powers

and the German Reich is an accomplished fact. The

conference is over. "

Source: Over the Top, August 2009

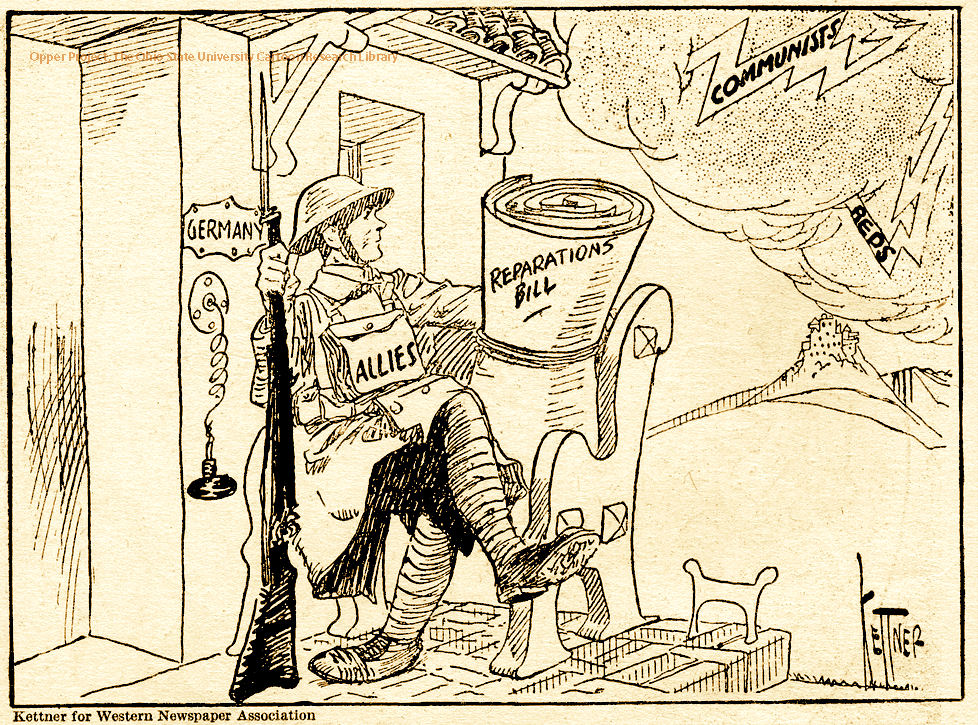

By 1921, "Cloudy and Unsettled"

Mangus Kettner, June 1921

(Billy Ireland Cartoon Library, Ohio State University)

Bringing the AEF Home

Troops of the AEF Arriving Home

Even after American troops irrevocably tipped the balance against Germany and the Central Powers and the war was ostensibly over, the Navy had much more to do. Even battleships and cruisers were pressed into the effort to bring home the soldiers and marines as quickly as possible, an effort which stretched into the summer of 1919.

|

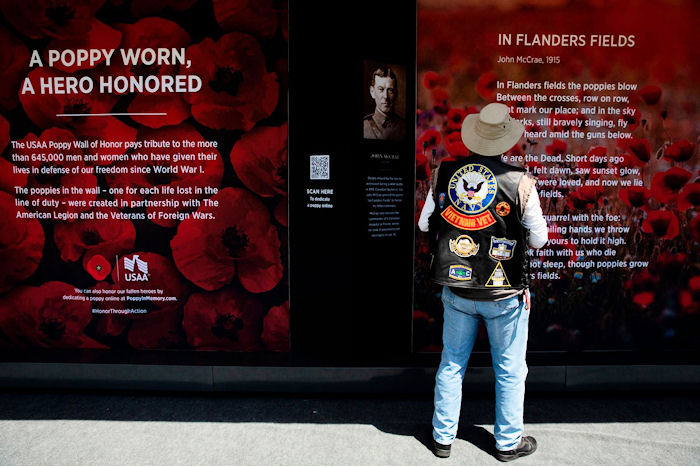

Memorial Day 2019

Ceremony at the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery and Memorial

In Washington, DC, A Vietnam Veteran and Rolling Thunder Member

Reads John McRae's Famous Poem

The Names of the 190 World War One Fallen of Erie County, PA, Are Read

by the Members of the County's WWI Centennial Committee

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications |

||

Order Our

|

Shop at |

Order the Complete Collection

|

A World War One Film Classic

Not to be confused with the silly reality TV production with the same title, The Trench, with a just-on-the-verge-of-stardom Daniel Craig in the lead, captures the claustrophobic feeling, tediousness, and random danger of trench warfare better than any film I've seen. The 1999 movie, set in the days just preceding the Battle of the Somme, was written and directed by WWI author William Boyd operating on a low budget. Maybe because of this, except for the concluding and somewhat predictable over the top sequence, the entire story is set in the frontline trenches and dugouts. Yet the dramatic result is most effective. By the end of the 98-minute production, the viewer is left with a sense of having spent a long stretch in a linear, open-air prison. The personalities of the soldiers are well explored, but at the center of everything is Sgt. Telford Winter (Craig). One of the things I especially liked about The Trench is the depiction of how it's the sergeants who actually run things at the cutting edge of any combat operation. Winter, burdened with a weak and erratic lieutenant (nicely portrayed by Julian Rhind-Tutt), carries a bigger load than most NCOs. The film is available on Netflix and for purchase on Amazon.

| Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

|

Content © Michael E. Hanlon