June

2020 |

|

|

|

Siberian Briar Patch

August 1918: AEF Siberia Arrives in Vladivostok

1919 U.S. Poster

|

In this month's issue of the Trip-Wire, we are completing the two-part presentation of Professor Christopher McMaster's study of America's intervention in Siberia during the Russian Civil War. The earlier sections of his article can be accessed HERE. In our earlier issue the political and diplomatic origins were covered as well as the character of the White and Red forces and that fascinating military wild card, the Czech Legion. In this issue, the main contributor focuses on the American experience, which seems in hindsight overly-precarious for the men dispatched to Siberia. Fortunately, it was kept from turning disastrous through the wise leadership of its commander, Major General William Graves.

Next month's special topic will be one of the most romanticized groups of participants in the war, those volunteer ambulance drivers. MH

Woodrow Wilson and the American Expeditionary Force to Siberia

Christopher T. McMaster, PhD

Part 4: The Military Mission

U.S. Commander William Graves and Staff with Russian White Commander Grigory Semenov

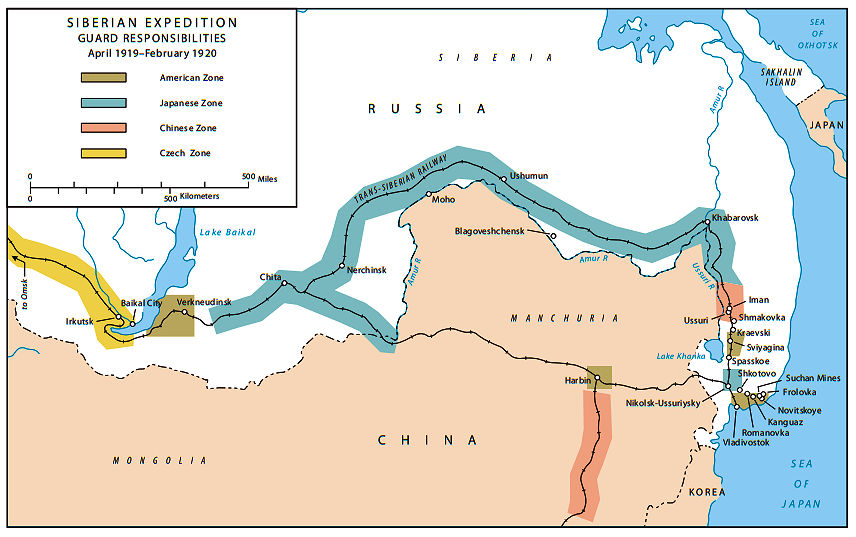

The military intervention into Siberia can be divided into three stages. These divisions are based more on official clarifications of duties, rather than any changes in military policy. A continuity, a consistency is present throughout the entire period of U.S. intervention, primarily to facilitate counterrevolution. The first stage is the period between the landing of U.S. troops and the acceptance by Washington of the Inter-Allied Railway Agreement (IARA) on 9 February 1919. The IARA imposed military control on the Siberian railways by clearly defining the respective responsibilities of the intervening forces on various sectors of the railway. For the Americans, this would confirm duties already assumed and create new ones.

Although obvious in whose interest the agreement worked, it was not until July that the purpose of the AEF was officially stated. During the summer of 1919, it was openly admitted that U.S. troops were in Siberia to maintain the supply line of the white leader, Admiral Kolchak. To the troops north of Vladivostok the latter was by that time an irrelevant technicality.

Japanese Troops Advancing in Force Against Red Forces

American troops arrived at Vladivostok to much cheer, mostly furnished by themselves and the crew and band of the USS Brooklyn that had been stationed in the waters around Vladivostok since March. The Japanese commander, General Kikuzo Otani, greeted the Americans with more seriousness and urgency. By letter he advised Colonel Henry Styre, in temporary command whilst Graves was in transit, that Vladivostok was in peril of imminent invasion. The Americans were needed for the city's defense.

Unwilling to remain inactive and unable to verify Otani's story, Styre consented to join in what was later to be known as the Ussuri Campaign. The several companies sent to help "defend" the city caught up with the Japanese after six days hard marching and served as rear flank to the Japanese and Czech forces who were pursuing the Bolsheviki northwards up the Trans-Siberian. The campaign culminated at Khabarosk, 475 miles from Vladivostok, where the Stars and Stripes and the Rising Sun were raised together in a significant show of unity.

U.S. Major Samuel Johnson Commanding the International Police Force of Vladivostok

Graves's first real examination of his troops came in October during a tour north of Vladivostok. He ordered back to Khabarosk any troops he found west of the city that had continued to follow the Japanese in their pursuit of the Red Guard. Graves could "see no reason for keeping troops at any of these stations," although a number of troops were kept at important locations between Khabarosk and Vladivostok. U.S. forces elsewhere got off to a less auspicious beginning, but equally partisan in the widening civil war. The majority of the 27th and 31st Infantry Regiments (dispatched from Manila) marched east of Vladivostok to establish a tent camp at Gornastaya Valley. The International Police Force was also created at this time under the command of a Russian-born American officer, Major Samuel Ignatiev Johnson.

An additional 250 troops were sent to the Soucha coalmines, located 75 miles northeast of the city. The mines consisted of 12 shafts and served as the fuel supply for the entire Primorsk province and for the operation of eastern Siberian railroads. The Suchan mines were the fuel for intervention and counterrevolution. The Allies set about immediately to secure the continued production of its coal. One of the first acts of the Allied leaders was to reinstate the previous mine manager, recently run out of the area by mine workers. To Graves, the mines proved to be the "stormy petrel" of his entire Siberian adventure. Most American causalities would be suffered protecting the spur lines linking the mines with the Trans-Siberian.

Guarding the Siberian Railroads

Right Click on Image to Enlarge in New Window

Visit Our Daily Blog

Click on Image to Visit

|

|

Different Perspectives

These links focus on the operations of the American forces deployed to Siberia, including material on the White Russian and Japanese contingents that were active in the area. See last month's issue of the Tripwire for resources on the rationale behind the intervention and the Czech Legion.

America's Siberian Adventure by MG William S. Graves

America's Siberian Adventure by MG William S. Graves

When Major Johnson Ran Vladivostok

When Major Johnson Ran Vladivostok

Smithsonian Magazine: The Forgotten Story

Smithsonian Magazine: The Forgotten Story

The Siberian White Army 1918-1923

The Siberian White Army 1918-1923

Review of Civil War in Siberia: The Anti-Bolshevik Government of Admiral Kolchak, 1918-1920

Review of Civil War in Siberia: The Anti-Bolshevik Government of Admiral Kolchak, 1918-1920

The Russian Expeditions: U.S. Army Campaigns (PDF)

The Russian Expeditions: U.S. Army Campaigns (PDF)

The Japanese Intervention in Siberia

The Japanese Intervention in Siberia

Guarding the Railroad, Taming the Cossacks

Guarding the Railroad, Taming the Cossacks

The AEF in Siberia (Video)

The AEF in Siberia (Video)

"Fiasco in Siberia" (The Canadian Viewpoint)

"Fiasco in Siberia" (The Canadian Viewpoint)

America’s Withdrawal from Siberia and Japan-US Relations (PDF)

America’s Withdrawal from Siberia and Japan-US Relations (PDF)

Stuck in Siberia

I sure don't like the cold weather.

Letter, Pvt. Floyd Pfost, 31st Infantry

Last to Leave

Of the Allies, the Japanese extricated themselves last. The Japanese

government had considered how to leave Siberia and the American

withdrawal provided a potential option. However, on 4 April, the

senior Japanese officers in the theater, without their government’s

knowledge, contrived an attack on Japanese interests which

“forced” the army to intervene and take Vladivostok. That, along

with an incident in February in which the Bolsheviks murdered

Japanese soldiers and civilians after taking them prisoner, sparked

a reinvestment in Siberia that included the seizure of northern

Sakhalin Island. The Japanese remained in Siberia until 1922, but

the tumultuous nature of local, national, and international politics

forestalled their attempt to create a buffer state there.

Doughboys at Ekaterinburg

Aboard American Red Cross Train #15, 10 July 1919:

Things are better at the front so we got started for Ekaterinburg with our cars and one car of medical supplies. We soon got into the Ural Mountains. They are beautiful; covered with pine, fir, and birch timber, and all kinds of wild flowers and ferns. [We saw] about 80 Cossacks on their horses, practicing on the drill field. They were galloping and swinging their sabers. We are held up for six hours, just 25 versts (approximately 10 miles) from Ekaterinburg, then got to the junction 4 versts from Ekaterinburg by the morning of 11 July.

We saw miles of refugees leaving Ekaterinberg [sic]. The [White] Army is retreating. The Bolsheviks are only 40 miles away. The American Vice Consul Mr. Gilman got on our train. I saw one group of 500 Bolsheviki prisoners, and several groups of 15-20 marched off to their destiny (execution). The Siberian Army of 40,000 is retreating before an army of 37,000 Bolsheviks. I went uptown and saw the home of Professor Ipatyev which was the prison of Tsar Nicholas and his family, where the Tsar, his wife Alexandra and son and daughters were murdered. All the stores are closed and houses vacated. Over 400,000 people have been made refugees and fled. This has happened in two days. We saw a carload of rotten horsemeat and people were picking it over.

By the efforts of General Jack (of the Canadian Army) we got our cars attached to the refugee train of the Russian Army staff and left Ekaterinburg at 1 pm, 12 July. We went 13 versts and stopped. The train ahead of us ran into the train ahead of it. One was a sanitary [hospital] train and the other a train of prisoners and refugees. It was an awful sight – about 30 cars were total wrecks. It took 5 hours to clear the track. We got started again at 7 o'clock.

Source: The Diary of Jesse A. Anderson, AEF Siberia

Doughboys in the Meuse-Argonne

Detail, Lost Battalion Memorial

Charlevaux Mill, France

From: Lost Battalion Tours / Rob Laplander & Mike Cunha, Tour Leaders

When: 8-15 August 2020

Details: Download Flyer

HERE.

For reasons well known to our readers, all the World War One organizations have

canceled their near-term events and are holding off announcing anything new. We will include news on any events that are scheduled for 2020 as soon as we hear about them.

|

|

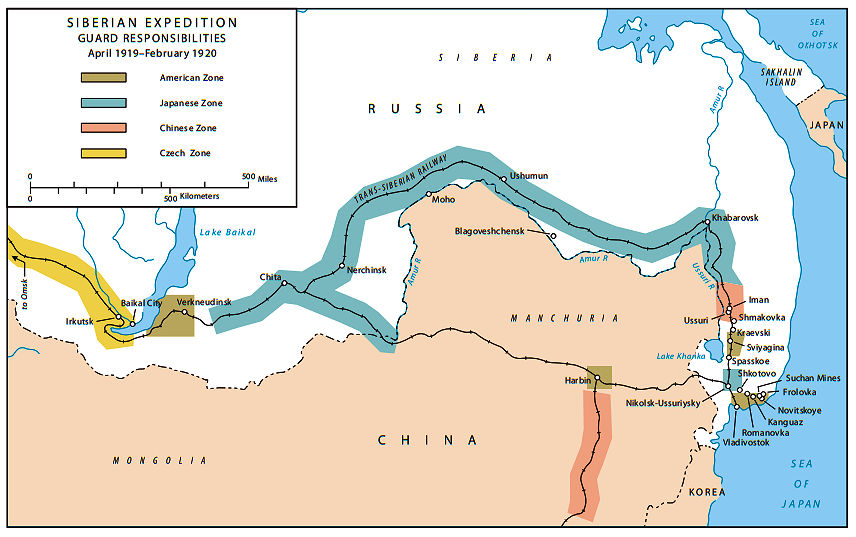

Part 5: Along the Railroad

U.S. Railroad Guard Detail

The Railway Agreement of February formalized some of these winter arrangements and added others. Although finalized in February, it took an additional two months to sort out which Allied force would protect each specific sector. (See map above.) Some 550 U.S. troops became responsible for the line running immediately out of Vladivostok to the town of Nikolsk-Ussuri, 68 miles north. Nikolsk-Ussuri, a town of 52,000 inhabitants, served as the juncture of the Ussuri line continuing to Khabarosk, and the Chinese Eastern Railroad which crossed Manchuria, later to reenter Siberia. At Spasskoe, continuing north, 1,700 troops were responsible for the length of line leading to the town of Ussuri and the 40-foot long bridge crossing the river Ussuri 217 miles from Vladivostok. Another 1,900 troops were assigned to guard a branch line from Ulgonaya to the coal mines at Suchan. Two thousand men were also stationed 1,700 miles west to maintain the stretch of line between Verkhe-Udinsk and Mysovaya, where the Trans-Siberian reached the network of 38 tunnels linking eastern and western Siberia.

With the railway Agreement practicably enacted, U.S. troops were immediately confronted by the dilemma of professed "non-interference" while participating in counterrevolution. Graves continued to maintain his "neutrality" regardless, which in essence was to keep his expeditionary force as disentangled from the mire of civil war as long as possible. In a proclamation given to his troops to distribute in their sectors he outlined that:

The sole object and purpose of the armed forces of the United States of America. . . is to protect the railroad and railway property and ensure the operation of passenger and freight trains through such sector without obstruction or interruption.

Hospital Car on American Train

The proclamation initially left the partisan guerrillas wondering just who the "Amerikanskije soldat" was. They soon made up their minds. As such order on the railroad only benefited one side, the U.S. soldiers soon became justifiable targets of the partisans. Just as it allowed supplies to roll to counterrevolution forces in western Siberia, Allied control of the railways made White control of the east possible. White representatives in eastern Siberia used order on the railroad to either starve or attack "Bolshevist" areas. "We are making this condition possible," Graves wired Washington, "by our presence here".

Even before U.S. sectors were chosen, U.S. troops north of Vladivostok were preparing for "anticipated...guerrilla warfare or general revolution with the recession of winter" due to the "unsettled political and economic conditions in eastern Siberia." As early as 14 March, partisans fired upon trains and "information was received that the partisans were recruiting for a vigorous spring drive against the Kolchak government." By late spring, U.S. forces finally settled in their allotted sectors, became swept up in that vigorous drive. Throughout March and April, attacks on rail freight, tack, and bridges increased. In May, Graves decided that to properly maintain "order" on the railways, U.S. troops would have to follow the attacking partisans into the surrounding countryside. The first active campaign began on 21 May in the vicinity of Maihe in the Ulgonaya-Suchan sector. Throughout the summer of 1919, the history of the AEF in eastern Siberia is one of skirmishes, attacks, and forays into the surrounding hills and valleys. On numerous occasions American combat patrols fought in conjunction with White Russian and Japanese forces. Over 200 U.S. soldiers were to fall in this partisan war. Twenty-five died on the morning of 25 June near the village of Romanovka during a dawn raid on their encampment.

The Landing of the Japanese Army, Welcomed by Every Nation,

at Vladivostok (1919 Print)

Part 6: Time to Leave

Back in Vladivostok

Washington was not deterred by news of these clashes. Indeed, during this time Wilson clearly stated whom the "Amerikanskije soldaty" were fighting for. Five days after the "Romanovka Massacre," Secretary of State Robert Lansing ordered the U.S. ambassador to Japan, Roland Morris, to travel to Kolchak's (provisional) capital, Omsk. His instructions were, first, to meet with Kolchak's Supreme Council, though "not involving any present recognition of Kolchak, leaves us free to take a sympathetic interest in Kolchak's organization and activities," and second, "to impress upon the Japanese Government our great interest in the Siberian situation and our intention to adopt a definite policy that will include the 'Open Door' to a Russia free from Japanese domination." When Morris finally reached Omsk he described the situation as "extremely critical." On the same date, Wilson pronounced to the Senate the necessity and reason for an expeditionary force in Siberia, which was maintaining order on the Siberian railways on which "the forces of Admiral Kolchak are entirely dependent."

By this time, however, the end of the White effort in Siberia was already in sight. Kolchak's army was demoralized. The Czech Legion was soon to quit the fight and begin to plan (once again) their exit from Russia, and the Trans-Siberian became increasingly congested with refugees fleeing the advancing Red Army. To Morris, for the U.S. to properly assist Admiral Kolchak it would have to extend massive monetary and military aid to his flagging forces and reinforce the AEF by "at least 40,000 troops." This Wilson simply could not afford to do, even if those measures would ensure a Kolchak victory. Wilson's pragmatic wait-and-see policy allowed him (and his expeditionary force) to exit Siberia when all hope of successful counterrevolution had vanished. With the fall of Omsk in November, this time had clearly arrived and plans for a U.S. withdrawal were laid.

The U.S. Army Transport Thomas Returned Many of the American Troops to the Philippines

Rather than idealistic or misguided, Wilson's Siberian policy, as executed by General Graves, allowed the president to cautiously play the situation with a minimum political and military cost. Graves resisted British demands for wider action and Japanese calls for assistance while the latter was suffering heavy losses against Bolshevik forces. The argument put forward that Wilson decided to intervene under pressure to be a good ally is countered by the fact that U.S. actions in Siberia served to antagonize all parties involved, Russian and Allied. By the winter of 1919-1920 all American forces were pulled back to Vladivostok and departing Siberia.

During the Civil War, however, that force served its purpose. By limiting its activities in Siberia it avoided being engulfed in the civil strife while supporting counterrevolution. Arms and supplies could continue to be shipped inland, White and Allied forces could continue to control the territory (at least around the railroad), and the Japanese could be observed and left to their own costly counterinsurgency campaign. President Wilson, in the meantime, could continue to proclaim the honorable intentions of U.S. intervention into Russian internal affairs while campaigning in Congress for a League of Nations based on self-determination.

|

100 Years Ago:

Treaty of Trianon Signed

4 June 1920–Minister of Labor Auguste Bernard Leads the Hungarian Delegation at the Trianon Palace

The Treaty of Trianon was signed between the Allied Powers of World War I, and Hungary, which lost 72 percent of its territory within the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. The treaty was signed on 4 June 1920. The Treaty of Trianon stated clearly that “the Allied and Associated Governments affirm and Hungary accepts the responsibility of Hungary and her allies for causing the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Austria-Hungary and her allies.”

The treaty was so unpopular that the Hungarian government had difficulty in finding anyone willing to sign it until Minister Plenipotentiary Alfred Detrashe Lazas and Minister of Labor Auguste Bernard agreed to do the task of agreeing to the breakup. A contributor to the Guardian called it "the most disastrous event in the long history of the ancient kingdom of Hungary was completed this afternoon in the long hall of the Grand Trianon at Versailles when her two representatives put their signature at the foot of the treaty."

The Hungarian delegation at Trianon argued for the case of self-determination as proposed by Woodrow Wilson, but the Allies mainly ignored this plea for the use of plebiscites. The city of Sopron was given a plebiscite as to whether the city wanted to remain in Hungary, which the population voted for. . . The Treaty of Trianon also stated that those Hungarians who now lived outside of Hungary’s borders would lose their Hungarian nationality within one year of the treaty being signed in June 1920.

Hungarian Territory Lost Through the Treaty

The new Hungary was a landlocked state and had no direct access to the Mediterranean Sea with its many ports. This had a major impact on her weakened economy as any trade that required to be moved by sea had to pay tariffs simply to reach a dock to enable it to be shipped abroad. Hungary’s army was reduced to 35,000 men with no conscription, and as a land-locked nation she was not allowed a navy. An air force was also banned.

The Treaty of Trianon ensured that the new Hungary would have minimal growth in her economic clout. This was, in fact, a deliberate policy. All the treaties signed by the defeated nations had at their core a desire to ensure that none of the Central Powers could ever become a threat to European peace again. Ironically, the unemployment that impacted Hungary in the interwar years was a primary reason for her association with Nazi Germany.

The anger of the Hungarian people over the Treaty of Trianon–both from those living within the new state’s borders and those forced to live outside of them–was long-lasting. Inside Hungary, government buildings kept the national flag lowered to show their grievance, and it was not until 1938 that the flags were flown at a third mast after the Munich Agreement returned southern Slovakia to Hungary–an area that included 550,000 Hungarians who made up 85 percent of the area’s population.

Sources: C. N. Trueman "The Treaty Of Trianon" at the Learning Center, Wikipedia, and the American Hungarian Federation (Map)

|

77th New York Metropolitan Division to Be Honored in France

Men of the 77th Division About to Attack the Argonne Forest

The episode of the Lost Battalion during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive is the most remembered and commemorated event of America's effort in the Great War. That patched-together unit trapped on that hillside for five desperate days came from men from the 77th Division, composed of men from New York City and the nearby communities. The Lost Battalion has its own monument overlooking the site and has been the subject of a well-done feature film. All well justified, of course. However, this focus has inadvertently led to a century-long neglect of all the other accomplishments of the full 77th Division, including those of the men who were trapped temporarily with the Lost Battalion, who–once sprung loose—carried on the fight right up to the Armistice.

Consider: No other division captured as much enemy territory during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive as the 77th Division. They advanced 37 miles in the 47 days of the operation, being in the line 32 days total. Including its earlier service in the Aisne-Marne sector, the Metropolitan Division suffered 10,194 casualties in action including 1,486 dead in the war. Yet, unlike many of the other divisions that served in France, the 77th has never had a monument to its accomplishments placed on the battlefields it liberated in 1918.

Villers devant Mouzon (Insert: Mock-up of Memorial)

Happily, however, that is about to change. A group of boosters is coordinating with numerous government officials, agencies, and foundations, in both the U.S. and France, to dedicate a private memorial to the U.S. 77th Division. The monument will be placed at the village of Villers-devant-Mouzon, on the Meuse river, which became the point of the division's farthest advance on 11 November 1918. Poetically, the Hillburn Granite Quarry of New York state has presented an exceptional design that is sure to highlight a true American story—from a small New York quarry to the banks of the River Meuse.

The dedication to the 77th Division Memorial is planned for Villers-devant-Mouzon on 28 June 2021, the anniversary of the signing of the Versailles Treaty. Planning for the event is being closely coordinated with the 77th Sustainment Brigade, Ft. Dix (which traces its lineage to the 77th Division), the 77th Infantry Division Reserve Officer Association, and the 50th Attack Squadron, Shaw AFB, which in October 1918 provided support for the Lost Battalion. All will be represented and included in the dedication.

The point of contact for the event is Col. Charles E. Metrolis, USAF, whose great-uncle Edwin Welch, was killed in a post-Armistice action, on a bridge over the Meuse river near Villers-devant-Mouzon. Contact him HERE if you have any questions about the dedication.

New York's Own Returns Home ( ARTICLE)

|

Support Worldwar1.com's Free Publications

|

Order Our

WWI Musical CD

Click on Image for Information

|

Shop at

Amazon.com

|

Order the Complete Collection

Over the Top Magazine

Click on Image for Information

|

A World War One Film Classic

Admiral, a 10-part (50 minutes each) 2009 Russian television production, is a beautifully filmed, deeply engaging, and sympathetic depiction of the last five years of the life of Admiral Alexander Kolchak. He is famous as the doomed White Russian commander on the eastern front of Russia's post-revolution civil war. The Kolchak we meet in this film is not the distant and temperamental figure presented in most histories. This admiral is patriotic, beloved by his fellow officers and sailors, religious, and overflowing with affection for his family. Except, though, that much of the narrative involves the interactions and incredibly toturous logistics of a three-way affair he carries on with his own wife Sofia and Anna, the wife of a subordinate officer.

Things I Liked: 1) Lots of detailed history about the naval wars in the Baltic and Black Seas, the post-revolutionary collapse of the Russian military, and (pertinent to this issue of the Trip-Wire) the civil war in Siberia; 2) Excellent casting, especially Andrei I. as Grigory Semenov, the brutal Cossack warlord that the American mission also had to deal with and the beautiful Elizaveta Boyarskaya as the irresistible (but annoying to everyone but Kolchak) mistress; and 3) Although the producers of Admiral were clearly making an anti-Bolshevik statement, Kolchak's White Army is shown–accurately, I think,–as equally brutal.

Things I Didn't Like: 1) The treatment of the Allied intervention seemed a little distorted, with the French role presented as critical and with minimal influence exercised by the other Allies, except for a brief, but important, appearance by a Japanese delegation; and 2) This series was tough to find with English subtitles. However, for those of you with Amazon Prime, it's available for streaming at no additional charge. A much shorter movie-length version with English sub-titles is available on YouTube, but it deletes tons of the historical content, in favor of the love story. [Boo!]

|

|

Thanks to each and every one of you who has contributed material for this issue. Until our next issue, your editor, Mike Hanlon. |

|

(Or send it to a friend)

(Or send it to a friend)

|

Design by Shannon Niel

Content © Michael E. Hanlon

|