| Quick Facts | Background | Battle Report |

| First Hand Accounts |

Quick Facts

-

Where: Southeast of Verdun

Where: Southeast of Verdun

Check the Location on a Map of the Western Front

-

When: September 12 - 16, 1918

When: September 12 - 16, 1918

-

AEF Units Participating: US First Army Composed of Three American and One French Corps

AEF Units Participating: US First Army Composed of Three American and One French Corps

Check the Units and Commanders on the Order of Battle

-

US Commander: General John J. Pershing

US Commander: General John J. Pershing

-

Opposing Forces: German Detachment C

Opposing Forces: German Detachment C

Memorable For: First US Operation and Victory by an Independent American Army

Memorable For: First US Operation and Victory by an Independent American Army

St. Mihiel From Across River Meuse

Background

Headquarters, United States First Army...became operational on 31 July... When the situation [in the Aisne-Marne] stabilized...Pershing obtained Foch's permission to take over the St. Mihiel sector instead, leaving three or four American divisions on the Vesle under French command. Preparations for the St. Mihiel attack [the first phase of an anticipated thrust into Germany through Metz] -- long planned by Pershing and his staff -- were begun at once.

The St. Mihiel salient, which had been formed in the fall of 1914, seriously hampered French rail communications between Paris and the eastern segements of the front. Pershing's First Army headquarters opened in the St. Mihiel area on 13 August. The concentration of troops for the operation began at once.

Mt. Sec - Captured Early In the Assault

US Memorial Visible On Peak

[Subsequently, negotiations between Foch and Pershing resulted in tabling follow up attacks through Metz into Germany. Pershing] promised that the St. Mihiel attack would be followed about two weeks later by a much greater one extending from the Meuse River to the Argonne Forest...As a limited offensive, the St. Mihiel operation would be a striking success. The First Army took 15,000 prisoners and 257 guns at a cost of about 7,000 casualties...

The offensive plan required two nearly simultaneous attacks:

Click here to view a map of the battlefield.

V Corps [26th, 4th and the 15th Fr. Colonial Divisions] would assault the west face of the salient, while IV Corps [1st, 42nd, 89th Divisions] and I Corps [2nd, 5th, 90th, 82nd Divisions] were driving against the southeast face. Meanwhile the II French Colonial Corps was to make a secondary attack against the nose, following up and exploiting the success of the two main attacks. [Units from the U.S. 80th Division, from First Army reserve, reinforced this effort after the first day. Thanks to the artillery furnished by the French, the First Army had over 3,000 guns to support the attack. French and British reinforcements brought the total number of airplanes up to nearly 1,500, which was the greatest concentration of air power up to that time...

Source: THE MILITARY HERITAGE OF AMERICA, by Dupuy and Dupuy

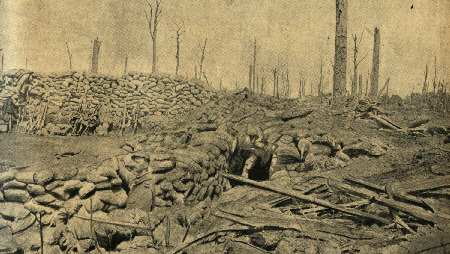

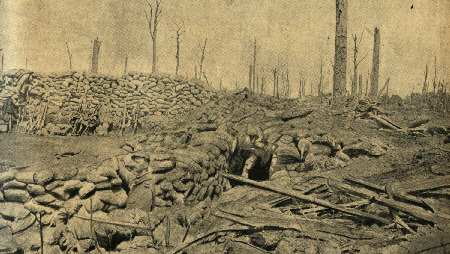

French Trenches From Which 90th Division Launched Their Attack

How St. Mihiel Looks to a Modern Soldier

Battle Analysis of St. Mihiel

By Captain Joseph H. Giese, US Army

From 12-16 September 1918, on the Western Front of France, one of the most significant battles of World War One was fought, the battle of St. Mihiel. The engagement was the first battle in which American led forces used a concise and comprehensive operations order allowing for independent initiative from their front-line commanders. The American Expeditionary Force (AEF), commanded by General John J. Pershing, faced several German armies who were defending a series of in-depth trenches. The trench boundaries started in the French fortified area southeast of Verdun, jutting south toward St. Mihiel, and then east to Pont-Au-Mousson.

The combat commanders participating in the operation, namely Colonel George S. Patton Jr. and his subordinate officers, believed that by rapidly adapting to a situation and through their personal leadership they could influence events on the battlefield. During World War II, General Patton drew upon these personal leadership principles when he prepared for an attack on the German salient in the Ardennes Forest. Today, the battle of St. Mihiel teaches modern tactical commanders the necessity to issue clear and concise operations orders that allow small unit leaders the freedom to carry out their commander's intent during the battle. By 1918, the number of offensives on the Western Front began to slow down into another phase of static warfare.

US St. Mihiel Cemetery at Thiacourt

Although the Western armies outnumbered the Germans, the strategic situation was turning into a murderous war of attrition in which each shattered side could no longer sustain an offensive. Yet, General John Pershing believed that a successful Allied attack in the region of St. Mihiel, the Metz, and Verdun would psychologically break the Germans will to fight. . . Besides, General Pershing knew the AEF's strategic setting dictated that the "clearing" of the rail and road communications into Verdun, and the capture of the German's key rail center at Metz should be the Americans' primary objective. Then the Americans, from their bases [now closer to] the Rhine, could launch offensives into Germany.

Tactically, the terrain became the biggest threat to the attacking forces. After five days of rain the ground became almost impassible to both the tanks and infantry. The weather section of I Corps operation order stated: "Visibility: Heavy driving wind and rain during parts of day and night. Roads: Very muddy." Another obstacle to the American operation were the many in-depth series of trenches, wire obstacles, and machine-gun nests that the Germans installed to augment their defensive positions. Therefore, "The Renaults designed to cross six-foot trenches in dry weather, were being forced by their crews to negotiate line after line of trenches that were eight feet deep and ten to fourteen feet wide 'in horrible mud.'" Further, the battlefields' key terrain was control of the villages: Vigneulles, Thiaucourt, and Hannonville-sous-les-Cotes because their rapid capture would ensure the envelopment of the German [divisions] near St. Mihiel. To do this, the American forces would breach the trenches and then advance along the enemy's logistical road network toward their objectives.

Lt. Col. Patton with FT-17 Renault Tank

Although the AEF was new to the French theater of war, they trained hard for several months in preparation of fighting against the German armies. Also, the British use of armor at the battle of Cambrai impressed General Pershing so much that he ordered the creation of a tank force to support the AEF's infantry. As a result, by September 1918, Colonel George S. Patton Jr. had finished training three tank brigades at [Langres], France for an upcoming offensive at the St. Mihiel salient.

In contrast, the Germans had almost complete knowledge available to them about the Allied offensive campaign coming against them. "One Swiss newspaper even published the date, time, and duration of the preparatory barrage." ( Still, the German [units] stationed in the salient lacked sufficient manpower, and effective leadership to launch a counter-attack of its own against the AEF. Thus, the Germans decided to pull out of the salient and consolidate their forces near the Hindenburg Line. The Allied forces discovered the information on a written order to the German Group Armies von Gallwitz. "The forces for repulsing a broad attack against the greater portion of the south front of Composite Army C are not at present available. The attack is therefore not to be met in the forward combat zone, but in this case, avoiding it by a withdrawal into the Michel [position] is contemplated, though only in the event of an enveloping attack." )

Rifle Pit of the 167th Infantry

Yet, General Pershing's operational planning of St. Mihiel had broken down the salient into several sectors. Each Corps had an assigned sector, defined by boundaries, that it could operate within. The American V Corps location was at the northwestern vertices, the II French Colonial Corps at the southern apex, and the American IV and I Corps at the south-eastern vertices of the salient.

Furthermore, General Pershing's intent was obvious, to envelope the salient by using the main enveloping thrusts of the attack against the weak vertices. The remaining forces would then advance on a broad front toward the direction of Metz. This pincer action by the IV and V Corps was to drive the attack into the salient and to link the friendly forces at the French village of Vigneulles while the II French Colonial Corps kept the remaining Germans tied down.

One reason for the American forces success at St. Mihiel was General Pershing's thoroughly detailed operations order. In fact, "...his [Pershing's] total offensive plan ran to only eight pages, about 150 less than the French proposal." Nevertheless, General Pershing's operation included detailed plans for penetrating the Germans' trenches using a "basic" combined arms approach to warfare. His plan had tanks supporting the advancing infantry, with two tank companies interspersed into a depth of at least three lines, and a third tank company in reserve. The result of the detailed planning was an almost unopposed assault into the salient. The American I Corps reached its first day's objective before noon, and the second days objective by late afternoon of the second day.

Fresnes-en-Woevre, Northernmost Objective of First Army

Another reason for the American success was the audacity of the small unit commanders on the battlefield. Unlike the World War One officers that commanded their soldiers from the rear, Colonel Patton and his subordinates would lead their men from the front lines. They believed that a commander's personal control of the situation would help ease the chaos of the battlefield. One example of subordinate leadership was "Second Lieutenant Julian K. Morrison, ...[who] came upon a German machine-gun nest as he led his tanks forward on foot. Struck by two bullets in the right hand, he continued forward and, armed only with his .45-caliber pistol, captured the crew." ( Indeed, Patton's aggressive leadership style seemed to have inspired and influenced several of his subordinates during the battle.

Yet, the hallmark of the battle was Colonel Patton's employment of unsupported tank platoons in a "cavalry-styled" attack outside the [small village] of Jonville. On the 13th of September, the 326th Battalion was southwest of St. Benoit where they were going to link with the enveloping units of General Samuel D. Rockenbach. However, an impatient Colonel Patton did not wait for the meeting. Instead, he sent a patrol of three tanks and five dismounted soldiers toward the [hamlet] of Woel to keep contact with the enemy. "Thirty minutes later the patrol was attacked by a force estimated to be at least a battalion of infantry accompanied by a battery of 77mm guns." Colonel Patton reacted to the fluid situation by sending the defenders a platoon of five tanks. The tanks joined into the fray, and without infantry support, drove the Germans about six miles to the outskirts of Jonville. "During the running battle the tankers killed or put into flight at least a dozen machine-gun crews and captured four 77mm cannon." Thus, Colonel Patton responded to the fluid situation by aggressively committing his "unsupported" tanks. Further, the tanks "cavalry-styled" attack caught the German infantry off-guard and gave the initiative back to the "outnumbered" Americans.

Evacuation of Wounded Near Les Eparges

In conclusion, the audacious leadership qualities and the operational planning present at the battle of St. Mihiel are still important factors for the modern military commander. Another major factor is the continuation of detailed planning that permits leaders to interpret their commander's intent. General George S. Patton Jr. continued to successfully use those skills throughout his lustrous career, especially at the Battle of the Bulge. Finally, "Had Pershing been allowed to conduct his offensive as planned, The First American Army probably would have penetrated German lines [further] and altered the strategic situation along the whole Western Front."

Captain Giese's analysis and other interesting material can be found at the World War I Page of TAC-CP.

Captured Field Piece

HOW IT LOOKED FROM THE GROUND AND AIR

Thurs.Sept. 12th, 1918.

Hiked through dark woods. No lights allowed; guided by holding on the pack of the man ahead. Stumbled through and under brush for about half-mile into an open field where we waited in a soaking rain until about 10 PM.

We then started on our hike to the St. Mihiel Front arriving on the crest of a hill about 1am. I saw a sight which I shall never forget. It was the zero hour. In one instant the entire front as far as the eye could reach in either direction was a sheet of flame while the heavy artillery made the earth quake. The barrage was so intense that for a time we could not make out whether the Americans or Germans were putting it over. After timing the interval between flash and report we knew that the heaviest artillery was less than a mile away and consequently it was ours.

Corporal Eugene Kennedy, 78th Division

Diary

The St. Mihiel Drive was on!

Leaping out of bed I put my head outside the tent. We had received orders to be over the lines at daybreak in large formations. It was an exciting moment in my life as I realized that the great American attack upon which so many hopes had been fastened was actually on. ... At 60 feet above ground [flying] straight east to St. Mihiel, we crossed the Meuse River and turned down its valley towards Verdun. Many fires were burning under us as we flew, most of them well on the German side of the river. Villages, haystacks, ammunition dumps and supplies were being set ablaze by the retreating Huns. ...One American army was pushing towards it from a point just south of Verdun while the other attack was made from the opposite side of the salient. Like irresistible pincers, the two forces were drawing nearer and nearer to this objective point....we found the Germans in full cry to the rear.....

That same night we were advised that the victorious Americans had taken

Thiaucourt - that scene of so many of our operations back of the lines...And we were also informed that at last Montsec had fallen! Its high crest dominated the entire landscape......The capture of Montsec was a remarkably fine bit of strategy, for it was neatly outflanked and pinched out with a very small loss indeed. Our infantry and Tank Corps accomplished this feat within twenty hours.

Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker, 94th Aero Squadron

Memoir

Friday, Sept. 13th.

A Great Day for the Americans! Our infantry is still pushing 'em back. Many prisoners are going by. We were at guns all morning, but had to stay in camp all afternoon. We are out of range and await orders to move up. Steady stream of men and material going up constantly. Two of our boys sneaked off and went up to the old Hun trenches and brought back lots of Hun souvenirs -- razors, glasses, pictures, equipment, etc.

Sgt. Edwin Gerth, 51st Artillery

Diary

|

|

Sources and thanks: The Panoramic photos are from the Library of Congress and the combat photos curtesy of Ray Metzger and Mike Iavarone. The two first-hand reports are from the Archives of the Hoover Institution. The Rickenbacker excerpt is from Fighting the Flying Circus. Capt. Geise gave us permission to reprint his article. MH |

To find other Doughboy Features visit our

Directory Page

|

For Great War Society

Membership Information

Click on Icon |

For further information on the events of 1914-1918

visit the homepage of

The Great War Society

|

Additions and comments on these pages may be directed to:

Michael E. Hanlon

(medwardh@hotmail.com) regarding content,

or toMike Iavarone (mikei01@execpc.com)

regarding form and function.

Original artwork & copy; © 1998-2000, The

Great War Society

|